Abbreviations

AME: Annually Managed Expenditure

CA: Carers Allowance

CoWA: Cost of Work Allowance

CPI: Consumer Prices Index

DfC/the Department: Department for Communities

DHP: Discretionary Housing Payment

DLA: Disability Living Allowance

DSS: Discretionary Support Scheme

DWP: Department for Work and Pensions

ESA: Employment and Support Allowance

GB: Great Britain

GPs: General Practitioners

HMRC: Her Majesty’s Revenue and Customs

HMT: Her Majesty’s Treasury

HSS: Housing Selection Scheme

LHA: Local Housing Allowance

MRC: Mandatory Reconsideration

MtC: Make the Call

NAO: National Audit Office

NIAO: Northern Ireland Audit Office

NIHE: Northern Ireland Housing Executive

PfG: Programme for Government

PIP: Personal Independence Payment

RPI: Retail Price Index

SSSC: Social Sector Size Criteria

UK: United Kingdom

UC: Universal Credit

WSP: Welfare Supplementary Payment

Key Facts

£7.3 billion

Annual social security expenditure for Northern Ireland

More than £1 billion

Disability Living Allowance (DLA) expenditure every year

More than £0.5 billion

Estimated cost of implementing welfare reforms over 10 years

£3 billion

Anticipated benefit savings from the introduction of Personal Independence Payment (PIP) and Universal Credit (UC) in Northern Ireland over 9 years

£0.5 billion

Funding set aside from the NI block grant for mitigation measures over the 4 year period to 2020

- The Northern Ireland Executive funded a mitigation package of £0.5 billion to “top-up” reductions in benefit payments for the four years ending March 2020

- Uptake on mitigation payments is below estimates, with £136 million of available funding not utilised in the first two years

- Various factors have led to these underpayments including delays in passing legislation

- The Cost of Work Allowance, a supplementary payment recognising employment expenses, has not been implemented

- The Northern Ireland Housing Executive receives over £16.5 million in mitigation payments every year

- There is no budget for mitigation expenditure post March 2020

- Universal Credit was introduced in Northern Ireland in September 2017, on a phased geographical basis, with 12,000 claimants processed by June 2018

- 82 per cent of claims for Universal Credit have been paid on time and in full: 52 per cent of claimants received an advance payment

- Managed migration will transfer existing claimants (around 300,000) of the six existing benefits to Universal Credit between July 2019 and March 2023

- Unique flexibilities for Universal Credit have been introduced in Northern Ireland

Personal Independence Payment is the new benefit replacing Disability Living Allowance for working-age claimants. One in nine of the Northern Ireland population claimed DLA in August 2016

- 41,000 new claims for PIP have been received with 46 per cent of these qualifying for payment of the new benefit

- 128,000 DLA recipients have been reassessed under PIP rules: 75 per cent of these qualified for payments under the new benefit rules

- 36 per cent of those eligible for PIP receive the enhanced rate for daily living and mobility components compared to the 15 per cent who received combined enhanced rates for DLA

Executive Summary

1. The Westminster Government paid over £212 billion on social security and tax credits in 2016-17. Northern Ireland’s share of this expenditure was £7.3 billion, comprising £6 billion on social security and £1.3 billion on tax credits.

2. Since 2010, the Westminster Government has been implementing an extensive programme of welfare reforms involving changes to benefit rates, entitlements and administration of payments. These reforms aim to simplify the benefits system, make it more affordable and create stronger financial incentives for individuals to move from benefits to employment. Reforms introduced between 2010 and 2015 were expected to realise savings of £17.2 billion across the United Kingdom (UK) by 2015-16.

3. Key welfare reforms, proposed in 2010, have been introduced in the rest of the UK from April 2012. However, the lack of political consensus delayed their introduction in Northern Ireland. Following the Fresh Start Agreement and a NI Assembly consent motion in November 2015, the Westminster Government was able to legislate for welfare reforms in Northern Ireland. Figure 1 compares the dates for implementation of key reforms in Great Britain (GB) and Northern Ireland.

Figure 1: Comparison of key welfare reform implementation dates

|

Benefit |

Change |

GB |

NI |

|---|---|---|---|

|

Contribution-based Employment and Support Allowance |

Limited to one year for certain people in the ‘work-related activity group’ |

April 2012 |

October 2016 |

|

Housing Benefit |

Social Sector Size Criteria (“bedroom tax”) introduced |

April 2013 |

February 2017 |

|

The Benefit Cap |

Cap on total benefits income for a household introduced |

April/Sept 2013 |

May/November 2016 |

|

Personal Independence Payment (PIP) |

Disability Living Allowance (DLA) for working-age claimants replaced by Personal Independence Payment |

April 2013 |

June 2016 |

|

Universal Credit |

Replaces working-age benefits and tax credits |

April 2013 |

Sept 2017 |

Source: NIAO

4. As part of the Fresh Start Agreement, the Northern Ireland Executive agreed to set aside £585 million for four years ending 2020 to “top-up” reductions in benefit payments resulting from UK welfare reforms and to establish a working group to consider the best use of this funding. In January 2016, the Working Group proposed a series of Welfare Supplementary Payments (WSPs) to reduce the impact of welfare reforms on the most vulnerable in Northern Ireland and provide support to claimants as they adapted to the changes. The Working Group recommended that:

- £501 million should be set aside for the mitigation measures over the four years to 2020 (see Appendix 3 for a detailed breakdown).

- a further £8 million should be committed by the Northern Ireland Executive to fund additional independent advice services.

5. The “bedroom tax”, the Benefit Cap and Personal Independence Payment are the welfare reforms that have attracted much publicity, particularly where they have resulted in welfare reductions for some households. Each of these reforms have been mitigated. However, the largest financial losses to large numbers of individuals and households (and largest financial saving to HM Treasury) have arisen from changes to Tax Credits, Child Benefit and a reduction in annual benefit rate uplifts since 2011. These welfare reforms have not been subject to mitigation measures in Northern Ireland.

6. In Northern Ireland, the Department for Communities (the Department) is responsible for administering £6 billion of social security payments directly or through the Northern Ireland Housing Executive (NIHE) or the Department of Finance’s Land and Property Services. The Department is managing the implementation of a complex programme of welfare reforms as well as new systems for administering mitigation measures.

Scope of this Report

7. This Report focuses on some of the key welfare reforms and local mitigation measures and assesses their impact. Part One sets out the background and rationale behind the extensive programme of welfare reforms introduced by the Westminster Government. Part Two examines the key changes to benefit rates and entitlements. Parts Three and Four look at Personal Independence Payment and Universal Credit. The issues which emerged from our engagement with the Third Sector are highlighted in Part Five. Part Six deals with expenditure, outcomes measurement and the impact on social housing providers, particularly NIHE.

8. We adopted a variety of methods during our review of welfare reforms in Northern Ireland and these are explained in more detail at Appendix 1.

Key Findings

Financial aspects of welfare reforms

9. HM Treasury directly funds social security expenditure and this is classed as Annually Managed Expenditure (AME). The costs of implementing welfare reforms (£566 million to date plus the cost of the managed migration phase of Universal Credit due to start in July 2019) and the £509 million set aside for mitigation measures and independent advice have been borne by Northern Ireland, through the block grant. No additional monies have been provided by the Westminster Government to cover these costs.

10. The Department’s business cases for various welfare reforms anticipate considerable savings. For example, the Department’s business cases for the implementation of PIP and Universal Credit in Northern Ireland estimates savings of around £3 billion by 2025-26.

11. HM Treasury benefits from AME savings arising from the introduction of welfare reforms in Northern Ireland. However, this results in less money going into the Northern Ireland economy. The implementation of welfare reforms may also have a detrimental impact on the Department’s ability to meet its Programme for Government targets for housing. For example, potential increases in rent arrears pose a risk to both the building and maintenance of social housing in the future.

Implementing welfare reforms

12. The Department has used the delays in implementing welfare reforms in Northern Ireland to take advantage of lessons learned from the experiences of the Department for Work and Pensions (DWP) in GB. In addition, flexibilities, agreed by local politicians, for Universal Credit including making payments twice a month and the housing cost element being payable directly to the landlord have been introduced in Northern Ireland in an effort to avoid increasing rent arrears. Further unique flexibilities have also been introduced in Northern Ireland in the implementation of PIP.

13. The Department is making good progress in reassessing around 128,000 existing working-age DLA claimants for Personal Independence Payment and expects to complete this work by April 2019. The Department had also processed 41,000 new claims to May 2018.

14. Universal Credit for new claims was introduced in September 2017 and by June 2018 there were approximately 12,000 new claims. The Department’s data shows that 82 per cent of these new claims were paid in full and on time. Approximately, 50 per cent of new claimants requested and received an advance payment of Universal Credit to help them through to their first payment. The managed migration phase, transferring around 300,000 existing claimants of legacy benefits and Tax Credits to Universal Credit, is planned to take place between July 2019 and March 2023.

Implementing and managing mitigation measures

15. Following the Working Group proposals in January 2016, claimants were paid mitigation payments for the Benefit Cap by June 2016. Mitigation schemes for other welfare reform measures followed. The Department successfully managed the implementation of administrative systems for mitigation measures to tight deadlines.

16. Funding of £214 million was available for mitigation of welfare reforms in 2016-17 and 2017-18. However, £136 million of the funding available in the first two years was not required. Approximately one-third of this funding is in respect of a key element of Working Tax Credits/Universal Credit mitigation that has not yet been introduced. In September 2017, Her Majesty’s Revenue and Customs notified the Department that payments made under this scheme would be taxable. The Department continues to explore options for an alternative scheme.

17. Administration has cost £9 for every £100 of mitigation payments made in the first two years, as opposed to the budgeted administration cost of around £7 per £100 of mitigation payments made. We anticipate that the proportion of administration costs will decrease over the next 15 months as uptake of mitigation payments increases.

Helping claimants navigate the benefits system

18. Many of the organisations and individuals consulted for this Report consider the benefits system to be even more complex than it was before welfare reforms were introduced. This is due to the many changes to entitlements and rules; the introduction of new benefits; administrative changes to payments; instances where existing and new benefits are operating in parallel; and, the gradual closing or migration of existing benefit claims as new benefits are introduced. Although the introduction of mitigation measures has provided additional monies to benefit claimants, it has further complicated the benefits system in Northern Ireland.

19. Apart from the £8 million of funding committed to March 2020 for additional independent advisory services, the Department also has its own “Make the Call” service. This provides advice and assistance to claimants regarding their entitlement to benefits and other Government support. Good quality focused advisory services are required to assist claimants in dealing with the complex benefits system, particularly if they are vulnerable. With funding for the independent advisory services ending in 2020, three years before the full roll out of Universal Credit, the Department must carefully consider how to make the best use of both external and internal advisory services.

20. The Department should also continue to build on its engagement with all stakeholders including claimants, third sector organisations and its own staff to enhance a shared understanding of how welfare reforms are working in practice. This feedback is crucial to improving communications with both claimants and Third Sector advocacy services.

21. The Third Sector strongly believes that continual support should be available for people with mental health problems and learning difficulties. Without such expert advice and support throughout the benefits process, there is a risk that some claimants will be unable to access their full benefit entitlements.

The impact of welfare reforms

22. Welfare reforms are also likely to have a major impact on housing in Northern Ireland as many social housing tenants rely heavily on benefits. The shortage of smaller properties in Northern Ireland may result in increased deductions for under-occupancy. This may in turn lead to increasing levels of homelessness, use of payday lenders and impact on the tenant’s credit worthiness. Increased levels of debt (in the form of rent arrears) could threaten the financial stability of housing associations posing a risk to both the building and maintenance of social housing in the future.

23. There is also a significant financial risk to the Northern Ireland Housing Executive, (NIHE), the largest social landlord in Northern Ireland, especially with the full roll out of Universal Credit and non-renewal of mitigation measures. Early indications from NIHE are that its rent arrears are increasing significantly, against a trend of decreasing arrears, prior to the implementation of welfare reforms. The Department told us that it is too early to determine whether rent arrears are increasing due to welfare reforms.

24. At its core, welfare reforms are about ‘making work pay’, that is, lower numbers of households on benefits and higher numbers in employment. Evaluating this aim should be at the centre of the Department’s outcome measurement work. It will be challenging to measure whether Universal Credit actually leads to more people in work, as it will be difficult to isolate its impact from other economic factors in increasing employment.

25. Similarly, evaluating the outcomes from welfare reforms in the coming years will also be a complex task. The Department has developed an outcomes- based evaluation strategy to measure the impact of welfare reforms and local mitigations on the claimant population, wider society and the economy. We encourage the Department to publish its detailed plan and timetable for this strategy as this would improve transparency and accountability.

26. The most recent research on the potential impact of welfare reform in Northern Ireland as a whole was carried out in 2013 by the Northern Ireland Council for Voluntary Action. This research is now dated and was completed before the majority of welfare reforms were implemented. The 2015 legislation requires the Department to report to the Northern Ireland Assembly on the operation of welfare reforms by December 2018. It is our view that the Department should include a preliminary assessment of the wider impacts of welfare reforms across Northern Ireland in this report. The Department should also consider a programme of more in-depth research, building on the work undertaken in 2013.

Overall Conclusions

27. The desired outcomes of the welfare reform programme are consistent with Programme for Government outcomes. Continued collaboration will be required across departmental boundaries to deliver these outcomes. In addition, the Department must continue to improve joined-up thinking and cooperation between its social security and housing functions.

28. The Department has shown that it is capable of implementing and adapting a wide range of programmes during a time of continued pressure to reduce costs and improve its services. The mitigation measures and flexibilities introduced by the Department together with lessons learned from DWP’s experiences, has led to a smoother implementation of welfare reforms in Northern Ireland to date, when compared to the rest of the UK.

29. The National Audit Office has concluded that the implementation of Universal Credit in GB has not delivered value for money to date. It is too early to assess the value for money of any of the welfare reforms in Northern Ireland. We also accept that it will be difficult for the Department to evaluate the intended outcomes. The challenge for the Department is to continue to deliver the planned benefits and efficiencies while maintaining the quality of its services. We intend to return to the assessment of value for money at a future date.

30. Claimants in Northern Ireland have not yet faced the full impact of welfare reforms because of the mitigation measures currently in place. These payments will cease in March 2020. Currently, there are no plans for further mitigations. While the absence of a Northern Ireland Executive exacerbates the position, it is imperative that options are available for Ministers to consider when the Assembly returns.

Recommendations

R1: We recommend that the Department uses feedback provided by all delivery partners, including programme managers and frontline staff, to establish a formal and enhanced understanding of how welfare reforms are working in practice. To improve accountability and transparency, the Department needs to collect and analyse the data and evidence from delivery partners, and regularly report on issues raised and progress made to address them.

R2: We recommend that the Department consults with the advisory sector, the wider Third Sector and DWP to continue to improve the clarity and simplicity of its communications with claimants and their representatives.

R3: We accept that there may be data protection risks in allowing implicit consent for Universal Credit. We recommend that the possibility of mitigating these risks should be explored, in consultation with DWP, especially for vulnerable claimants.

R4: We recommend that the Department evaluates and reports on the value for money of the additional independent advisory services supported by mitigations funding. The Department should carefully consider how to make the best use of both external and internal advisory services post March 2020.

R5: We recommend that the Department undertakes a short review exploring the reasons behind the lower than expected uptake of mitigation payments. This may provide an evidence base to indicate how it can make better use of the mitigation funding for the remaining two years. We acknowledge there will be very limited scope to amend the existing schemes in the continued absence of the Assembly.

R6: We recommend that the Department publishes a detailed plan and indicative timetable for the expected outputs from its outcomes-based evaluation framework.

R7: We recommend that the Department takes the lead on a programme of research to assess the wider impacts of welfare reforms across Northern Ireland society.

Part One: Introduction

1.1 Welfare reform is not a recent phenomenon. Successive governments have implemented various programmes of reform since the creation of the modern welfare state more than 70 years ago, and continue to do so. In its broadest sense, spending on welfare includes health, long-term care, education, social housing, social security benefits (including state pension) and tax credits for people of all ages.

More than £7 billion is spent on social security benefits in Northern Ireland every year

1.2 In 2016-17, £174 billion (including £6 billion of Northern Ireland payments) was paid out in benefits and state pensions across the United Kingdom (UK). The Department for Work and Pensions (DWP) administers most benefits in Great Britain (GB) either directly or through local authorities. In Northern Ireland, the Department for Communities (the Department) administers most benefits either directly or through the Northern Ireland Housing Executive (NIHE) / the Department of Finance’s Land and Property Services. Her Majesty’s Revenue and Customs (HMRC) administers Personal Tax Credits and Child Benefit across the UK. This will continue until all existing claimants have either transferred to Universal Credit or left the Tax Credits regime. HMRC paid out £27 billion on Tax Credits and £11.7 billion on Child Benefit in 2016-17. Northern Ireland’s share of this expenditure is estimated to be around £1 billion on Tax Credits and £350 million on Child Benefit (see Figure 2).

Figure 2: Expenditure on Social Security, Tax Credits and Child Benefit in 2016-17 across the United Kingdom

|

Great Britain £’bn |

Northern Ireland £’bn |

Total £’bn |

|

|---|---|---|---|

|

Benefits and State Pensions |

168.0 |

6.0 |

174.0 |

|

Tax Credits |

26.0 |

1.0 |

27.0 |

|

Child Benefit |

11.4 |

0.3 |

11.7 |

|

Total |

205.4 |

7.3 |

212.7 |

Source: DWP Annual Report and Accounts 2016-17

HM Treasury anticipates significant UK financial savings from welfare reforms

1.3 In 2010, the Westminster Government announced an initial programme of welfare reform involving changes to benefit rates and entitlements, assessment of need and administration of payments. The aims of this reform programme are to:

- simplify the benefit system making it fairer and more affordable;

- create stronger financial incentives for individuals to move from benefits to employment; and

- reduce levels of fraud and error.

1.4 Additional welfare reforms were announced in subsequent UK Budgets and Autumn Statements throughout the 2010-15 Westminster Parliament. A further package of reforms was announced in 2015 and these are still rolling out. The scale of reforms means that the majority of working-age households claiming benefits, and households in work but on low pay, have seen their benefits changed. This Report focuses on some of the key changes and their impact in Northern Ireland.

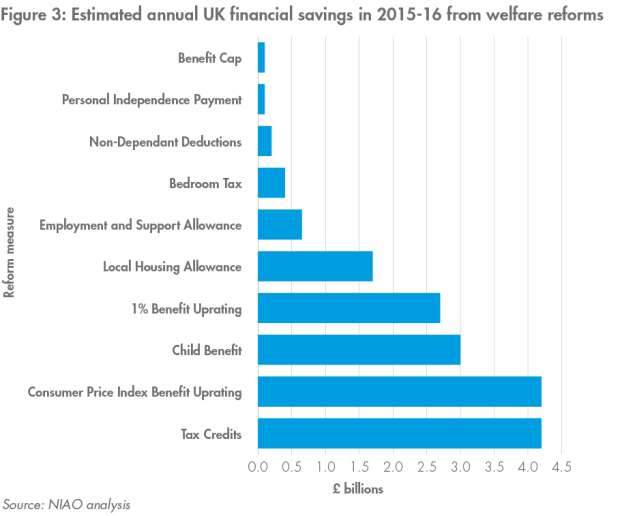

1.5 The 2010 Budget anticipated that these measures would reduce overall UK spending on social security and Tax Credits by £11 billion in 2014-15. The reforms introduced between 2010 and 2015 were expected to increase the annual savings to £17.2 billion by 2015-16. The breakdown of the expected savings for each welfare reform measure is set out in Figure 3.

The Westminster Government legislated for welfare reforms in Northern Ireland in November 2015

1.6 Welfare policy is devolved to Northern Ireland but funded by the Westminster Government. There is an agreed principle that Northern Ireland’s welfare policy will broadly mirror that in place in the rest of the UK. Should the Northern Ireland Assembly decide not to implement Westminster policy then any additional spending must be funded from the devolved budget.

1.7 Social Security benefit expenditure in Northern Ireland is categorised as Annually Managed Expenditure (AME) and funded directly from HM Treasury based on actual claimant entitlements. AME is not part of the Northern Ireland Executive managed block grant. This means that HM Treasury meets increases in demand for AME funding. Conversely, HM Treasury benefits from any AME savings resulting from the introduction of welfare reforms in Northern Ireland.

1.8 Since 2011, reforms have been rolling out in England, Scotland and Wales. In October 2012, the Department introduced its Welfare Reform Bill to the NI Assembly but this was not passed due to a lack of political consensus. Two years later, in December 2014, the Stormont House Agreement participants agreed to start implementing welfare changes in 2015-16. In May 2015, the Welfare Reform Bill was again not passed by the Assembly. In November 2015 under the Fresh Start Agreement and following a NI Assembly consent motion, the Westminster Government was able to legislate for welfare reforms in Northern Ireland.

1.9 These delays led to additional costs for the Department including £173 million of HM Treasury deductions from the devolved budget to reflect higher Northern Ireland benefit expenditure. However, there has also been a positive impact, with a number of early implementation problems arising elsewhere in the UK (see paragraph 1.14) being resolved by the time reforms were introduced in Northern Ireland. Appendix 2 compares the dates for implementation of key reforms.

The Northern Ireland Executive agreed to allocate £585 million to mitigate the impact of welfare reforms

1.10 Following the Stormont House Agreement, the Department developed a framework of mitigation schemes to support claimants who may be disadvantaged by anticipated changes to the welfare system. The Westminster Government did not provide additional funding for these schemes, which are funded from the Northern Ireland block grant. As part of the Fresh Start Agreement the Northern Ireland Executive agreed to:

- set aside £585 million over the four years to 2020 to ‘‘top-up’’ reductions in benefit payments resulting from UK welfare reforms. The position was to be reviewed in 2018-19; and

- establish a working group to bring forward recommendations on how this funding could best be used within the agreed financial structure (see Figure 4).

Figure 4: The agreed financial structure of the mitigations package in the Fresh Start Agreement

|

2016-17 £’m |

2017-18 £’m |

2018-19 £’m |

2019-20 £’m |

Total £’m |

|

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

Welfare |

75 |

90 |

90 |

90 |

345 |

|

Tax Credits/Universal Credit |

60 |

60 |

60 |

60 |

240 |

|

Agreed Amount |

135 |

150 |

150 |

150 |

585 |

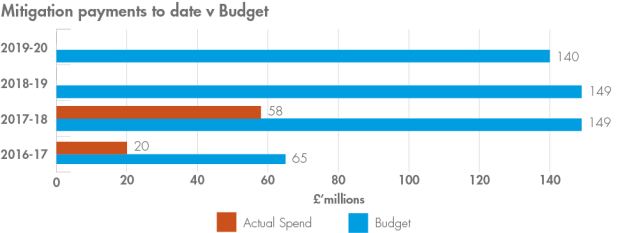

1.11 In January 2016, the Welfare Reform Mitigation Working Group proposed a series of Welfare Supplementary Payments (WSPs). The payments were envisaged to reduce the impact of reforms on the most vulnerable and provide support to claimants as they adapted to the changes. WSPs relating to disability, Carers Allowance and Employment and Support Allowance (ESA) were to be paid to claimants for one year, whereas payments mitigating the Social Sector Size Criteria, commonly referred to as bedroom tax (see paragraph 2.15) and the Benefit Cap (see paragraph 2.19) were to be paid for up to four years. Mitigation payments relating to Universal Credit were to be paid for the three years to 2020. The Working Group estimated that, using the agreed financial structure, mitigation scheme payments would cost £501 million over four years (see Figure 5 for a summary and Appendix 3 for a detailed breakdown). The Working Group further suggested additional, free of charge, independent advice services should be established to help claimants during the transitional period. The Northern Ireland Executive committed £8 million of funding up to March 2020 for these additional advisory services (see paragraph 5.1).

Figure 5: Welfare Reform Mitigation Working Group summary budget for the programme of mitigation measures

|

2016-17 £’m |

2017-18 £’m |

2018-19 £’m |

2019-20 £’m |

Total £’m |

|

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

Welfare |

46 |

89 |

93 |

84 |

310 |

|

Tax Credits/ Universal Credit |

14 |

53 |

49 |

49 |

165 |

|

Programme Administration |

5 |

7 |

7 |

7 |

26 |

|

Total |

64 |

149 |

149 |

140 |

501 |

Other UK devolved administrations have also been mitigating the impact of welfare reforms

1.12 Since 2013-14, the Scottish Government has fully mitigated the bedroom tax, using Discretionary Housing Payments (DHP). From April 2017, it has also provided additional DHP funding to mitigate the impact of other aspects of welfare reform including changes to Local Housing Allowance (see paragraph 2.14) and the Benefit Cap. The Scottish Government has also allocated additional funding to support independent advice services provided by the Third Sector.

1.13 The Welsh Government has decided to prioritise investment in the construction of one and two bedroom properties (as under-occupancy leads to reductions in benefits) and the provision of frontline advice services.

The National Audit Office has been closely monitoring the implementation of welfare reforms in Great Britain

1.14 The National Audit Office (NAO) and the Public Accounts Committee at Westminster have published a number of reports scrutinising the implementation or changes to Universal Credit (see paragraph 4.20), Employment and Support Allowance, Personal Independence Payment (PIP), the Welfare Cap, Benefit Sanctions and Housing Benefit. These reports focus on the challenges faced by DWP, highlighting pitfalls and lessons learned in implementing a complex programme of welfare reforms. The NAO concluded that DWP continues to make progress in delivering difficult major programmes despite early failings. However, it relied too heavily on reacting to problems and was not always able to anticipate likely points of failure.

1.15 The Department is having to catch up with DWP in the implementation of reforms in Northern Ireland and the lessons learned elsewhere provide a valuable source of reference.

Part Two: Changes to benefit rates and entitlements

The Westminster Government anticipates nearly 40 per cent of benefit savings from changes to benefit uprating for 2015-16

2.1 In June 2010, the Westminster Government announced that from April 2011, benefits would be uprated according to the Consumer Prices Index (CPI) instead of the Retail Price Index (RPI) or the Rossi Index. As the CPI tends to rise more slowly than the RPI, this change would gradually reduce the value of benefits received by claimants in real terms. This change brought the uprating of benefits in line with CPI, which the Government uses to measure inflation.

2.2 In his Autumn Statement in December 2012, the Chancellor of the Exchequer said that it was “not fair to working people” that out-of-work benefit rates had increased by 20 per cent since 2007 while average earnings had risen by around 10 per cent. Given this, and the general economic situation, he proposed limiting increases in certain working-age benefits to one per cent a year for the next three years from April 2013. The Westminster Government expected to save around £7 billion across the UK from these measures, nearly 40 per cent of the savings for 2015-16. (See Figure 3)

2.3 Since April 2016, the value of certain benefits and tax credits has been frozen at 2015-16 cash values until 2019-20, that is four years at zero per cent. The Department estimates that the overall impact on Northern Ireland of the four year zero per cent uprating policy is a further saving to the Westminster Government of around £0.2 billion.

2.4 There are no mitigation measures to alleviate reductions in benefits in real terms due to changes in benefit uprating.

There have been significant changes to Tax Credits and Child Benefit

2.5 Tax Credits aim to provide support for families with children and ensure that work pays more than welfare support. Since 2011-12, payments through the tax system of Child Tax Credit and Working Tax Credit have seen a series of adjustments. For example, from 2012 the number of hours a couple with children need to work to become eligible for Working Tax Credits was increased from 16 to 24 hours per week. Couples earning over £41,000 no longer qualify for Child Tax Credit and there were reductions in the childcare element of Working Tax Credits. Further changes to Tax Credits/Universal Credit were announced in 2015 for example, income threshold reduction, income rise disregard in tax credits and support for children.

2.6 Child Benefit is paid to households per child up to the age of 16 or, if they remain at school or further education, up to the age of 19. Child Benefit has been withdrawn from households where at least one adult earns over £60,000.

2.7 The Welfare Reform Mitigations Working Group recommended that households claiming Working Tax Credit or Universal Credit should be entitled to supplementary payments in recognition of the expenses those in employment incur. This is known as the Cost of Work Allowance and further detail can be found at paragraph 4.14.

There are two types of Employment and Support Allowance (ESA)

2.8 ESA supports people whose disability or health condition causes them to have limited capability for work. There are two types:

- contribution-based ESA, which depends on national insurance contributions previously paid by claimants; and

- income-related ESA, which is means-tested and can be paid on its own or as a top-up to contribution-based ESA. This will eventually be replaced by Universal Credit (see paragraph 4.1).

2.9 Claimants undergo a medical test called the Work Capability Assessment and during the Assessment Phase, a standard rate or ‘basic allowance’ is paid. Claimants assessed as having limited capability for work receive an additional amount on top of the basic allowance, depending on whether they are allocated to the ‘work-related activity group’ or the ‘support group’ for people with severe disabilities who are not expected to work. At May 2018, there were 129,000 claimants of ESA in Northern Ireland, of whom 47 per cent (60,000) suffered from psychiatric disorders.

2.10 In January 2011, Atos was awarded an initial seven year contract to undertake medical examinations in Northern Ireland. These are used to assess entitlement to a range of benefits including ESA, Universal Credit and Disability Living Allowance (DLA). This contract was later extended by two years to June 2020. The total contract costs to March 2018 are £66 million.

Since October 2016 certain individuals can only receive payment of contribution-based ESA for one year

Key facts and figures

- Savings anticipated from this measure are £60.6 million to 2024-25.

- The estimated implementation cost for the Department is £5.9 million to 2024-25.

- Mitigation funding of £24 million was set aside for claimants for the two years to March 2018.

- Mitigation Payments of £3.2 million were paid out in 2016-17 and £6 million were paid out in 2017-18.

- The Department told us that all claimants who were entitled received mitigation and claimants will continue to receive mitigation during the lifetime of the scheme. Furthermore, the Department will fund mitigation for claimants to March 2020.

2.11 Claimants qualifying for the ‘work-related activity group’ are expected to participate in voluntary work or work trials and failure to do this can lead to benefit sanctions. From October 2016 in Northern Ireland, such claimants can only receive payment of contribution-based ESA for one year. This change applied retrospectively, which meant that claimants already in receipt of contribution-based ESA for one year or more lost the entitlement to payment of ESA immediately.

2.12 The Department estimated in June 2016 that 3,600 claimants would be affected by the time limiting of contribution-based ESA. The additional cost to the Department of implementing this was estimated at a cumulative figure of £5.9 million up to 2024-25. The Department estimated benefit savings over this period to be £60.6 million.

2.13 The Mitigations Working Group recommended that:

- Claimants be given three months’ warning that ESA entitlement will end.

- An automatic check be in place to determine if there is entitlement to income-related ESA instead.

- If there is no entitlement to the above option, a Welfare Supplementary Payment, equivalent to the loss of benefit, should be made for up to one year, provided there is continuing medical evidence of limited capability for work.

The Local Housing Allowance rate for private sector tenants was capped in April 2011

2.14 Low-income private sector tenants are eligible for Housing Benefit for their rent up to a certain rate, as determined by Local Housing Allowance (LHA) rates. Since April 2011, across the UK, maximum caps were introduced per number of bedrooms and rates reduced considerably when compared to private sector rental prices. This means that the lowest 30 per cent of private sector rents should be affordable on Housing Benefit alone. Discretionary Housing Payment is available to certain tenants living in the social sector or private sector who are in receipt of Housing Benefit or, in some circumstances, Universal Credit and who are experiencing a shortfall in their rental payments.

The “bedroom tax” was introduced in Northern Ireland in February 2017

Key facts and figures

- Savings anticipated from the bedroom tax are £92.9 million for the five years to 2020-21.

- The estimated implementation cost for the Department is £0.7 million.

- Mitigation payments of £91 million were set aside for claimants to March 2020.

- Mitigation payments of £2.3 million were paid out in 2016-17 and £22 million were paid out in 2017-18.

2.15 In April 2013 in GB, the rate of Housing Benefit paid to tenants in social homes was reduced for households living in properties that were considered larger than required. This measure, the Social Sector Size Criteria (SSSC), commonly referred to as the bedroom tax, was introduced in Northern Ireland in February 2017. Its aim is to encourage better use of limited housing stock, encourage mobility within the social rented sector, align social and private rented sector policies and contain increasing Housing Benefit costs.

2.16 Full mitigation for NIHE and Housing Association tenants was provided through an allocation of £91 million until March 2020 from the Northern Ireland block grant. In 2017-18, £22 million in mitigation was paid to almost 39,000 social housing tenants (an average of around £570 per household). See Case Example 1.

Case Example 1: Mitigation of Social Sector Size Criteria

Mr and Mrs A are a working-age couple in receipt of Housing Benefit of £76.92 per week. They live with their daughter aged 17 and son aged 16 in a 3 bedroom NIHE property. When SSSC was introduced on 20 February 2017 their social house was considered to be fully occupied.

Their daughter left home on 13 June 2018 and, under SSSC rules, the family is now under-occupying the 3 bedroom property. Eligible rent has reduced by 14 per cent resulting in a weekly reduction in their Housing Benefit of £10.77 (leaving the family with Housing Benefit of £66.15 per week).

NIHE notified the Department of this under-occupancy and the family automatically received a Welfare Supplementary Payment of £10.77 per week to cover this shortfall. Mr and Mrs A will continue to receive this until the Welfare Supplementary Payment scheme ends on 31 March 2020 or they have a relevant change in circumstances.

Source: Department for Communities

2.17 The additional funding required by the Department to implement the bedroom tax was estimated at £0.7 million, the majority of this being project staffing costs. The Department estimated that the savings for Housing Benefit expenditure in the five years to March 2021 would be £92.9 million. In 2016-17, £2.3 million of savings were realised in line with estimates. These savings are expected to rise as future social housing allocations, transfer requests and mutual exchanges will consider need and the number of bedrooms. Given the current structure of the social housing portfolio, this is likely to be a challenging target (see paragraph 6.37).

Non-dependant deductions have increased

2.18 In certain circumstances, an adult person who normally lives in a claimant’s house, but is not their partner, may be treated as a non-dependant, for example, adult sons or daughters. Deductions for such non-dependants will depend on their income. These deductions may be reduced or not apply if they are also claiming benefits. The deductions may not be made if the claimant or their partner are in receipt of certain benefits. Under welfare reforms, Housing Benefit or the housing element of Universal Credit has been reduced to reflect an anticipated increase in contributions to the rent by non-dependants. There are no mitigation measures to alleviate reductions in Housing Benefit due to increases in non-dependant deduction rates.

A Benefit Cap was introduced in June 2016

Key facts and figures

- Savings anticipated from this measure are £30 million to 2022-23.

- The estimated implementation cost for the Department is £2 million to 2022-23.

- Mitigation Payments of £25 million were set aside up to March 2020.

- Mitigation Payments of £1.7 million were paid out in 2016-17 and £3.9 million were paid out in 2017-18.

2.19 In June 2016, a Benefit Cap (the Cap) was introduced in Northern Ireland, three years after being adopted in GB. For the Cap to apply a household must be in receipt of Housing Benefit or Universal Credit which is then reduced accordingly.

2.20 The Department estimated that it would need additional funding of £2 million to 2022-23 to implement the Benefit Cap. The Department estimated monetary savings of £30 million to 2022-23. Savings realised for 2016-17 are approximately £2 million, in line with estimates.

2.21 The Northern Ireland Executive allocated £25 million from the Northern Ireland block grant for the four years ending March 2020 to mitigate reductions in benefits due to the Cap. Payments are made to whoever receives Housing Benefit. This could be the claimant, a registered landlord or a letting agent. If benefits are reduced, further Welfare Supplementary Payments will not be increased but claimants can apply for Discretionary Housing Payments to cover the difference. In 2017-18, the total amount of mitigation paid to claimants for the Benefit Cap was £3.9 million. See Case Example 2.

Case Example 2: Mitigation of the Benefit Cap

In December 2016, Mrs B who lives with her husband and three children in a private rented property had her total benefit income assessed by the Benefit Cap Team in the Department. They determined that the household income exceeded the income threshold of £20,000 per year by a weekly amount of £11.07.

NIHE reduced the amount of her Housing Benefit by £11.07 and the Welfare Supplementary Payment team in the Department arranged for a payment equal to the reduction to be paid to her landlord every four weeks. This will be paid until the mitigation scheme ends on 31 March 2020, or until there is a relevant change of circumstances, at which point Mrs B will have to pay her landlord the shortfall.

Source: Department for Communities

2.22 From June 2016 until April 2018, 2,790 households had their benefits capped in Northern Ireland. New households continue to be capped and the average weekly impact is a reduction of £49. Around eight per cent of households are capped by more than £100 a week.

Part Three: Personal Independence Payment (PIP) replaces Disability Living Allowance for Working-Age Claimants

Key facts and figures

- Savings anticipated from the change to PIP are £1.6 billion to 2024-25.

- The estimated implementation cost for the Department is £0.4 billion to 2024-25.

- Mitigation payments of £139 million were set aside for claimants to March 2020.

- Mitigation payments of £1 million were paid out in 2016-17 and £21 million were paid out in 2017-18.

More than £1 billion pounds was spent in Northern Ireland on Disability Living Allowance (DLA) in 2015-16

3.1 DLA provides a cash contribution towards extra costs arising because of an impairment or health condition. It is a tax-free benefit for people with disabilities who need help with mobility or care costs. Eligibility is based on a person’s need for help with personal care or getting around.

3.2 Historically, there has been high concentrations of claimants receiving DLA in Northern Ireland, with annual expenditure increasing from £550 million in 2004-05 to £1,004 million in 2015-16. While expenditure on DLA did decrease to £895 million in 2017-18, when PIP expenditure is included, the total increases to £1.1 billion. The number of DLA claimants at August 2016 was approximately 214,000, which represented around one in nine of the population (in the rest of the UK one in twenty claimed DLA). Seventy-five per cent or 160,000 of these claimants had indefinite awards.

3.3 We asked the Department to explain why the total expenditure on DLA and PIP continues to increase. The Department explained that the reassessment of working-age DLA claimants is still ongoing and will not be completed until 2019.

128,000 existing DLA claimants are to be reassessed for entitlement to PIP

3.4 PIP is the new benefit replacing DLA for working-age people who have a disability or long-term health condition (see Case Examples 3a and 3b). PIP comprises two components, a daily living and a mobility component, which can be paid at either a standard or an enhanced rate.

3.5 Like DLA, PIP is not affected by income or savings, is not taxable and is payable whether you are in work or not. However, there is no automatic entitlement to PIP even for people with indefinite DLA awards. A fundamental element of the new benefit is the introduction of an assessment, which considers an individual’s ability to carry out key daily living and mobility activities. The majority of awards are for a fixed term with regular reviews.

Case Examples 3a and 3b: Transferring from DLA to PIP

- a: Ms C was receiving DLA of £22 each week. When the period of her DLA award ended, she was reassessed for PIP. She continued to receive DLA at the existing rate during this period. Following the decision that she did not meet the PIP eligibility criteria, she asked for it to be reconsidered. When this did not alter the original decision, she lodged an appeal. Upon receipt of her appeal, she qualified for a weekly Welfare Supplementary Payment of £22 from the date her DLA award had ended until the Department was notified of the outcome of the appeal.

- b: Mr D was getting DLA of £44 each week from 3 September 2012 for an indefinite period. While he was being reassessed for PIP, his DLA continued to be paid at the existing rate. He was subsequently awarded the enhanced daily living component and the enhanced mobility component of PIP (£141.10 weekly) payable from 18 October 2017.

Source: Department for Communities

3.6 Since June 2016, all new working-age claimants and existing working-age claimants of DLA reporting a change in circumstances are being assessed for entitlement to the new benefit. The process of reassessing around 128,000 existing working-age DLA claimants started in December 2016 and will continue until April 2019. DLA payments continue unchanged for about 86,000 individuals who on 20 June 2016 were aged 65 or over (or under 16 years old), provided they continue to meet the eligibility criteria. The delay in implementing legislation in Northern Ireland, between 2013 and 2016, resulted in more than 14,000 additional over 65s being eligible for indefinite awards of DLA and not required to claim and be assessed for PIP.

Capita was appointed to provide the independent assessment service for PIP

3.7 In November 2012, Capita was awarded a five year £59 million contract to provide a PIP independent assessment service for Northern Ireland (this contract was part of a UK wide procurement process). However, due to a lack of political consensus, the PIP assessment service was not operational until June 2016. Capita was paid £2.1 million for costs incurred on staffing and accommodation in the period between 2013 and 2016. Subsequently the contract was extended to July 2019 (aligning with DWP contract expiry dates) and its value is now £80 million. We intend to review the management and performance of this contract at a later stage.

3.8 The development of the PIP assessment was carried out in collaboration with an advisory group of independent specialists in health, social care and disability and included engagement with people with disabilities and disability organisations. The new assessment was subject to consultation in both Great Britain and Northern Ireland. Health professionals called Disability Assessors, based at one of the nine consultation centres across Northern Ireland, carry out the assessments. From June 2016 until April 2018, the private sector provider has been paid £45 million for over 100,000 assessments, which are either paper-based review (20 per cent) or a face-to-face consultation (80 per cent). Claimants who are terminally ill, and not expected to live for more than six months, are fast-tracked and do not have to attend consultations. A Department Case Manager makes the final award decision, having considered all the information including the claim form assessment report and other supporting evidence from the claimant.

The Department has introduced flexibilities for PIP that are unique to Northern Ireland

3.9 The Department has introduced a number of flexibilities that are unique to Northern Ireland including investigating reasons for non-return of the PIP application form and failure to attend assessments to establish if there is good reason for this. Benefit is suspended during this period but is not disallowed.

3.10 The Department told us that when a claimant is being reassessed from DLA and receives either a reduced or nil award their case is automatically referred to the mitigations team. WSPs available to those left financially worse off after PIP assessments are:

- DLA claimants who appeal after not qualifying for PIP receive a WSP equal to the weekly rate of the original DLA payment. The payment stops following the outcome of the appeal but payments already received are not recoverable where an appeal has been unsuccessful.

- DLA claimants qualifying for PIP after reassessment or appeal but losing £10 or more per week, receive a WSP equal to 75 per cent of the weekly loss for up to one year.

- DLA claimants with a conflict related injury, not qualifying for PIP, but scoring four points or more in the assessment, are entitled to a WSP equal to the standard rate of PIP for up to one year.

Claimants who lose entitlement to Disability Premiums, Enhanced Disability Premiums or Severe Disability Premiums in the reassessment for PIP will receive a WSP for up to one year to cover the loss. Although Carers Allowance is not changing directly, a carers entitlement to the allowance may be affected, if the person they look after does not qualify for PIP, or is not awarded the qualifying daily living component. Carers affected receive a WSP for up to one year to cover their financial loss. The payment stops if the person being cared for is no longer entitled to a WSP for the loss of DLA. Case Example 4 demonstrates some of the complexities of such cases.

Case Example 4: Mitigation of transfer from DLA to PIP

Mr E was in receipt of a total weekly DLA rate of £108.25. In December 2017, he was advised his DLA was ceasing and he was eligible to make a claim for PIP.

The Department’s Case Manager decided that Mr E was entitled to the mobility component of PIP at the weekly rate of £59.75 with effect from 23 May 2018. As Mr E was at least £10 per week financially worse off as a result of the introduction of PIP, he was entitled to a WSP of 75 per cent or £36.38 of the weekly shortfall in benefit (£108.25 - £59.75 = £48.50). The Department’s PIP Team made a referral to its WSP Team and Mr E will receive £145.52 every four weeks from 23 May 2018 to 22 May 2019.

Mrs E, his full time carer, was in receipt of Carers Allowance for her husband. Following the above decision, her Carers Allowance of £64.60 also ceased from May 2018.

The Department’s Carers Allowance Branch made a referral to its WSP Team and a payment of £258.40 will now be made every four weeks to Mrs E for the period 28 May 2018 to 27 May 2019.

Source: Department for Communities

3.11 Figure 6 summarises the number of claimants and total value of Welfare Supplementary Payments for 2016-17 and 2017-18.

Figure 6: Summary of DLA/PIP Welfare Supplementary Payments

|

2016-17 |

2017-18 |

|||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

Number of Claimants |

Budget £’000 |

Spend £’000 |

Number of Claimants |

Budget £’000 |

Spend £’000 |

|

|

Carers |

150 |

2,000 |

82 |

1,530 |

7,000 |

2,254 |

|

DLA: Payment up to appeal |

530 |

1,000 |

583 |

4,960 |

15,000 |

10,500 |

|

DLA: 75% of loss greater than £10 |

870 |

1,000 |

313 |

9,010 |

10,000 |

6,223 |

|

DLA: Conflict Related |

- |

- |

- |

10 |

4,000 |

8 |

|

Adult Disability Premium |

110 |

1,000 |

102 |

1,280 |

6,000 |

2,437 |

|

Total |

1,660 |

5,000 |

1,080 |

16,790 |

42,000 |

21,422 |

Source: Department for Communities

46 per cent of new claims and 75 per cent of reassessments for existing DLA claimants have qualified for PIP

3.12 The Department has been reassessing approximately 5,500 DLA claimants each month for PIP. By May 2018, 72,000 of these reassessments had been completed, with an average clearance time of 12 weeks. Another 41,000 new claims have also been processed. The Department is making good progress and expects to complete all the reassessments by April 2019. Figure 7 sets out the four key performance targets for PIP which have been achieved.

Figure 7: Key performance targets for PIP

|

Targets |

Performance up to quarter ending June 2018 (percentage) |

|---|---|

|

Process 99% of PIP claims within 16 weeks of PIP2 being received. |

99.3 |

|

95% of claims are financially accurate. |

99.5 |

|

Telephony – 90% of calls answered. |

91.5 |

|

Complaints to be less than 1% of caseload. |

0.71 |

Source: Department for Communities

3.13 By June 2018, 800 existing DLA claimants invited for a PIP reassessment have telephoned the Department to explain that they do not wish to be assessed for PIP and a further 1,200 existing DLA claimants failed to make contact regarding reassessment for PIP. These 2,000 existing working-age DLA claimants, the majority having been in receipt of indefinite awards, represent three per cent of DLA claimants invited for reassessment for PIP and are now no longer entitled to DLA or PIP.

3.14 Forty-six per cent of new claims (18,600) for PIP and 75 per cent of reassessments (53,900) from existing DLA claimants have been eligible for PIP. Of those eligible for PIP, around 36 per cent receive the enhanced rate for both the daily living and mobility components. This compares to 15 per cent receiving the combined enhanced rates for DLA.

3.15 If a claimant does not qualify for PIP or disagrees with the Department’s decision, they may request a Mandatory Reconsideration (MRC). MRC was introduced by the Department in 2016 in an effort to resolve disputes at the earliest possible opportunity. If the decision remains unchanged, an appeal can then be made to an independent tribunal. See Figure 8 for further details.

Figure 8: PIP Mandatory Reconsiderations and Appeals as at September 2018

|

Number since 20 June 2016 |

As a % of PIP decisions made |

|

|---|---|---|

|

Number of PIP decisions made |

140,000 |

100 |

|

MRC requested |

33,777 |

24.0 |

|

Number of decisions changed on MRC |

6,615 |

4.7 |

|

Number of Appeals received |

12,662 |

9.0 |

|

Number of Appeals heard |

5,283 |

3.7 |

|

Decisions upheld at Appeal |

2,377 |

1.7 |

|

Decisions overturned at Appeal |

2,906 |

2.0 |

Source: Department for Communities

3.16 Figure 8 shows that 140,000 PIP decisions were made since June 2016, with seven per cent (or 9,521) changed following Mandatory Reconsideration (6,615) and Appeal (2,906). Fifty-five per cent of cases heard at appeal were overturned. This may, in part, be due to additional evidence being made available by claimants. The Department explained that GP records are made available for Tribunals in Northern Ireland. Also, that the overturn rate is affected by Tribunals applying the recent (see paragraph 5.26) Judicial Review judgements in GB.

3.17 The cost of implementing PIP in Northern Ireland is estimated to be £0.4 billion until 2024-25. The main costs include those for assessment provider, internal PIP staffing, appeal costs, project team and consultancy expenditure.

3.18 The total benefit savings up to 2024-25 are estimated to be £1.6 billion. If the estimates are accurate then savings are likely to outweigh the cost of implementing PIP. We intend to monitor progress on anticipated monetary savings.

An Independent Review of the PIP Assessment Process has made a number of significant recommendations

3.19 Legislation requires the Department to carry out an independent review of the PIP assessment process after the first two years. The first Review for Northern Ireland was published in June 2018. The Review notes that issues raised are not unique to Northern Ireland and are comparable to matters identified in a similar review completed in 2014 in GB. The Review concluded that the current assessment process is viewed with “distrust and suspicion”; is “fragmented” and “impacts negatively on both claimants and those who support them”. Moreover, the stress and fear caused by the face-to-face assessment was considered to impact on the health and wellbeing of claimants.

3.20 The Review made 14 recommendations on:

- Improving communications with claimants, carers and medical professionals.

- Administrative improvements to the assessment process.

- The clinical judgement of medical practitioners, indicating that claimants having a terminal illness should be sufficient for special rules to apply.

- The improvement of availability and quality of medical evidence.

- Developing criteria detailing which conditions would be more appropriately addressed through a paper based review approach.

- Enhanced training for assessors dealing with certain groups of conditions.

The Department provided an interim response to this Review in November 2018.

Part Four: Universal Credit and changes to the administration of benefit payments

Key facts and figures

- Savings anticipated from Universal Credit are £1.3 billion to 2025-26.

- The estimated implementation cost for the Department is £58 million.

- £22.6 million costs were incurred during the period April 2011 to March 2016, when the political situation led to delays in implementing Universal Credit.

- Managed migration, transferring existing legacy benefit claimants to Universal Credit, is planned for July 2019 to March 2023.

- The Cost of Work Allowance, mainly payable to low-income families who may or may not receive Universal Credit, for which £105 million of funding was set aside, has not been introduced.

Universal Credit is intended to simplify the administration of six benefits

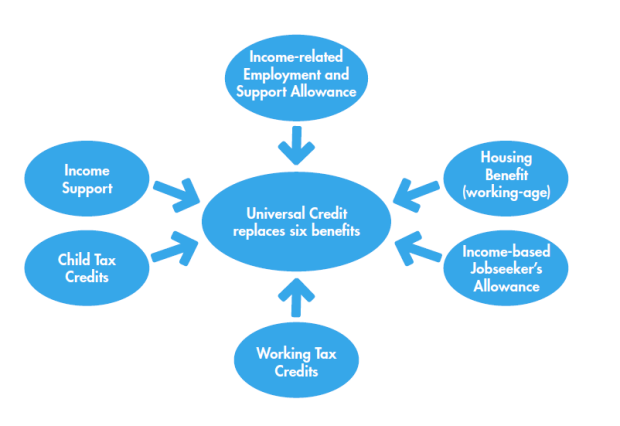

4.1 In October 2010, the Westminster Government announced proposals to replace working-age benefits and tax credits with a single Universal Credit. This replaces Child and Working Tax Credits, income-based Jobseeker’s Allowance, income-related ESA, Housing Benefit (working-age) and Income Support. Entitlement to Universal Credit depends on financial and personal circumstances. Claimants are entitled to a standard amount plus additional amounts relating to children, housing costs, capacity to work, caring responsibilities and childcare costs.

4.2 Universal Credit is intended to:

- simplify the administration of the benefit system by replacing six benefits;

- be easy to access, as claims are made online;

- ensure people receive their full entitlement to benefits by bringing the individual benefits together;

- encourage more claimants into work; and

- be payable when circumstances change for claimants, so they do not have to reapply as they move in and out of work. Benefit systems are integrated with HMRC systems, resulting in earnings being automatically taken into account when calculating Universal Credit payments.

The Universal Credit process requires significant cultural change

4.3 The Universal Credit process requires significant cultural change for both benefits’ staff and claimants. For staff, this means shifting from a benefit-processing role to a personalised support approach, with interactions tailored to each claimant’s needs. Support is provided to help those who are out of work (and able to work) move into employment. Support is also available for those in work to increase their hours and become less reliant on benefits. There is an emphasis on building a relationship between the claimant and their Jobs and Benefits Office work coach. This change in approach requires considerable commitment from public sector staff, including structured retraining programmes.

4.4 Universal Credit places an onus on claimants who are able to look or prepare for work to do so and this is a condition of receiving the benefit, known as conditionality. Conditionality requires claimants to sign and comply with a Claimant Commitment, drawn up by the claimant and their Jobs and Benefit Office work coach. This Commitment applies to claimants who continue to be paid Jobseeker’s Allowance and those who have claimed Universal Credit.

4.5 A financial sanction may be applied if a claimant fails to comply with the Claimant Commitment; does not provide a good reason for non-compliance; does not engage or does not provide satisfactory evidence. The sanction periods in Northern Ireland (7 days to 18 months) are shorter than in GB (7 days to 36 months). This is in consequence of amendments tabled by the then Minister for Social Development during the passage of the Welfare Reform Bill through the NI Assembly. Decisions can be challenged by requesting a Mandatory Reconsideration and, if this is unsuccessful, it can then be appealed.

Over 300,000 households in Northern Ireland will be transferred to Universal Credit

4.6 The Department has estimated that around 312,000 households in Northern Ireland will be transferred to Universal Credit; 114,000 households will be entitled to receive more per week (£26 on average); 126,000 households will receive less per week (£39 on average) and 72,000 households will have no change to their entitlement (see Figure 9). The Department estimates an overall decrease in benefit entitlements of approximately £105 million each year (based on 2018-19 prices). This estimate does not take into account the cost of transitional protection for Universal Credit claimants (see paragraph 4.9) or potential savings due to reductions in fraud and error.

4.7 Universal Credit has been rolling out since 2013 in GB and was introduced for new claims in Northern Ireland on a phased geographical basis starting in September 2017. By June 2018, around 12,000 new claimants or claimants with changes in circumstances had claimed Universal Credit. Individuals claiming legacy benefits may need to move to the new system if there is a change in their circumstances and they live in an area where Universal Credit has been rolled out. This is referred to as natural migration.

4.8 The next implementation phase, known as managed migration, will transfer existing claimants of the legacy benefits over to Universal Credit between July 2019 and March 2023. This phase presents a significant challenge for the Department with Jobs and Benefits Office staff dealing with significant increases in claimant volumes. This includes Tax Credits’ claimants also moving into the Universal Credit system.

Transitional protection is available to managed migration Universal Credit claimants across the UK

4.9 Transitional protection will be available to all claimants who are moved over to Universal Credit from a legacy benefit as part of the managed migration of claimants. This means they will not lose out in cash terms even if their entitlement is lower on Universal Credit than legacy benefits. This protection will continue (without any uprating) until either a claimant’s circumstances change significantly (a significant change could include: a partner leaving or joining a household; a member of the household stopping work; or the Universal Credit award ending) or their Universal Credit award “catches up” due to annual uprating. The Department has advised that the Social Security Advisory Committee has consulted on the transitional protection arrangements and the regulations will be subject to parliamentary approval.

4.10 If a claimant’s circumstances change prior to the roll out of the managed migration phase and this results in a natural migration to Universal Credit, the claimant is not entitled to transitional protection. The Department, using August 2018 Universal Credit caseload forecasts estimates, that by the end of March 2023 there will be 78,000 natural migrations to Universal Credit. The Department told us that it is not possible to estimate the transitional protection savings as it will depend on the managed migration option chosen.

4.11 Local politicians agreed the following package of payment flexibilities for Northern Ireland:

- Payments are made twice a month (rather than monthly as in GB to help low-income households manage tight budgets.

- The housing element is paid directly to landlords to avoid increasing rent arrears. Households may opt out of this arrangement, subject to them meeting specific criteria primarily around avoiding future arrears.

- Payments can be split between two members of the same household.

4.12 To assist claimants with the move to Universal Credit the Mitigations Working Group recommended that:

- £25 million be set aside over four years to fund the administration of payment flexibilities.

- Low-income working families and others who are claiming Working Tax Credit/Universal Credit should be entitled to a Welfare Supplementary Payment (known as the Cost of Work Allowance from 2017-18 to recognise the additional expenses incurred by households in employment. The Working Group set aside £105 million (20 per cent of the measures agreed) over three years for this allowance.

4.13 To assist claimants during the roll out of Universal Credit the Department set up a contingency fund of £7 million, from 1 November 2017, for non-repayable emergency payments to cover hardship situations. There has been a low uptake of this grant to date with 115 payments totalling £17,000 up to March 2018.

A key element of Working Tax Credit/Universal Credit mitigations has not been introduced

4.14 In September 2017, after four months of negotiations and clarifications, HMRC notified the Department that payments made under the proposed Cost of Work Allowance scheme would be treated as taxable income. This would mean that low-income families would lose a proportion of this WSP to tax, and additionally it would have implications for their Tax Credit position. This important element of the Working Group’s work has not been delivered. The Department told us it is committed to introducing a Cost of Work Allowance scheme and continues to explore options for an alternative scheme.

4.15 In March 2017 the Department estimated:

- the cost of implementing Universal Credit across Northern Ireland as £58 million; and

- additional funding of £33 million would be required, above what was currently being paid out for existing benefits, for operational delivery of Universal Credit.

4.16 The Department also spent £22.6 million (including project team costs of £18 million) during the period April 2011 to March 2016, when the political situation led to delays in implementing Universal Credit. These delays, outside the Department’s control, have led to significant additional costs to the Northern Ireland taxpayer.

The Department’s business case estimates savings of £1.3 billion from Universal Credit

4.17 The Department’s business case estimated that the Westminster Government will save £1.3 billion through the implementation of Universal Credit in Northern Ireland over the ten years to 31 March 2026. The majority of savings are through changes to benefits, however the Department also expects to deliver savings from lower levels of fraud. This is estimated to save £45.9 million over ten years.

4.18 The Department also anticipated efficiency savings of an estimated £26 million by 2025-26, having compared the cost of administering Universal Credit as opposed to legacy benefits. It has set a target to reduce its annual administration costs by 6.2 per cent by April 2022.

4.19 Given the objectives of Universal Credit, the Westminster Government needs to be able to estimate how many people will move into work because of its introduction. DWP calculated that Universal Credit would reduce worklessness in GB by approximately 250,000 people. We note that the Department’s business case states that there was no Northern Ireland equivalent of this analysis, as not all of the data used by DWP is available for Northern Ireland. In the absence of specific Northern Ireland data, a read across from the DWP forecast for GB was calculated by the Department, that is, pro rata 2.4 per cent (or 8,420 people) reduction in worklessness for Northern Ireland. Based on this 2.4 per cent reduction, the indirect benefits over the appraisal period are estimated to be £24 million savings for the National Health Service and £145 million in increased income for individuals.

The National Audit Office concluded that Universal Credit in GB has not delivered value for money to date

4.20 In its latest review of Universal Credit the National Audit Office (NAO) concludes that:

- It has taken significantly longer to roll out than intended;

- It may cost more than the legacy benefit systems it replaces;

- DWP will never be able to measure whether it has achieved its stated goal of increasing employment; and

- It has not delivered value for money and it is uncertain that it ever will.

4.21 The NAO has seen evidence that many people have suffered difficulties and hardship during the roll out of the service. 21 per cent of new claims have not been paid in full and on time, with nearly 60 per cent of new claimants receiving a Universal Credit advance (interest free loan) to help them manage.

4.22 The NAO believes that DWP must now ensure that the programme does not expand before current operations can deal with higher claimant volumes arising from managed migration. Furthermore, DWP must learn from the experiences of claimants and third parties, as well as the insights it has gained so far.

It is too early to assess the delivery of Universal Credit in Northern Ireland

4.23 The roll out of Universal Credit to June 2018 has seen just over 12,000 new claims. 79 per cent of these claims were made remotely, with claimants attending Jobs and Benefits Offices making 21 per cent of claims. 25 per cent of claimants were able to verify their identity using the government’s online verification system.

4.24 The target for a first payment of Universal Credit following a new claim is now five weeks. Up to June 2018, the Department’s data shows that 82 per cent of new claims were paid in full and on time. While this is better than DWP’s figure of 79 per cent, 18 per cent or just over 2,000 new Universal Credit claims in Northern Ireland were not paid in full and on time at the end of the first assessment period. 6,471 new claimants or 52 per cent requested and received an advance payment of Universal Credit to help them through to their first payment. This provides evidence that claimants have difficulties managing financially, until their first payment. Figure 10 provides further performance data for Northern Ireland.

Figure 10: Universal Credit performance data as at 30 June 2018

|

Data |

Percentage |

Number |

|---|---|---|

|

Number of claimants |

12,459 |

|

|

Number of claims |

11,371 |

|

|

How claimants applied for Universal Credit |

||

|

Remotely |

78.72 |

8,952 |

|

In a Jobs and Benefits Office |

21.04 |

2,392 |

|

Telephone |

00.24 |

27 |

|

How claimants’ verified their identity |

||

|

Online |

25 |

3,074 |

|

In a Jobs and Benefits Office |

75 |

9,215 |

|

Advances paid |

52 |

6,471 |

|

Payments on time and in full for the first assessment period |

82.04 |

9,329 |

|

Payments on time and in full across all assessment periods |

89.18 |

Source: NIAO, based on Department for Communities data

A new Discretionary Support Scheme has been introduced

4.25 The Social Fund was designed to help people on very low incomes manage large or unexpected expenditure and cope with emergencies. In April 2013, the administration of its discretionary elements was passed to the devolved administrations in Scotland, Wales and Northern Ireland who were to determine the most appropriate arrangements for their own jurisdictions. The Social Fund was previously funded directly by Westminster and elements of the block grant.

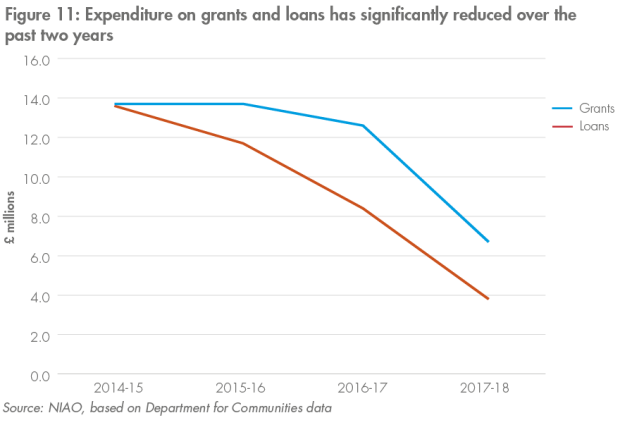

4.26 In 2012, the Northern Ireland Executive proposed a new Discretionary Support Scheme (DSS), offering both grants and loans. The Department estimated that introducing the new devolved DSS would result in additional administration costs of £32 million over the ten years to 2022. The DSS went live from November 2016. Loans and grants are available to claimants who are in work or receiving benefits, but annual income must not be above a set threshold of £16,286. This is based on the national minimum wage of an adult aged 25 or over which increases annually in line with government legislation. Applications can be made via a Freephone service or in person at a Jobs and Benefits Office.

4.27 Between 2014-15 and 2017-18, the number of grants and loans awarded has declined from 115,000 to 47,000, a reduction of 60 per cent. As a result, annual expenditure has also reduced from £27 million in 2014-15 to £11 million in 2017-18 (see Figure 11). The Department explained that the reduction is due to the criteria for loans and grants becoming more stringent.

4.28 Setting specific eligibility criteria is at odds with the concept of discretionary awards and alleviating claimant vulnerability. We note that similar schemes in Scotland and Wales (see paragraph 4.30) have not set such prescriptive eligibility criteria. The tighter criteria for the DSS may have contributed to the significant drop in expenditure over the past two years. The Department does not consider that access to DSS is significantly less generous than the corresponding provisions in Scotland and Wales. It explained that in particular the Welsh system uses entitlement to a specified income-related benefit, which can exclude claimants not on benefit.

4.29 The new devolved DSS is in the early stages of operation in Northern Ireland. It is too early to tell if administering DSS locally results in a more effective and efficient use of the limited financial resources available to target those most in need.

4.30 In Scotland, the Scottish Welfare Fund has replaced discretionary elements of the Social Fund. This is a national grant scheme delivered on behalf of the Scottish Government by the 32 local authorities. In Wales, the Discretionary Assistance Fund replaced the Social Fund.

Part Five: How welfare reforms are working in practice

Additional funding of £8 million was committed for independent advisory services up to 2020

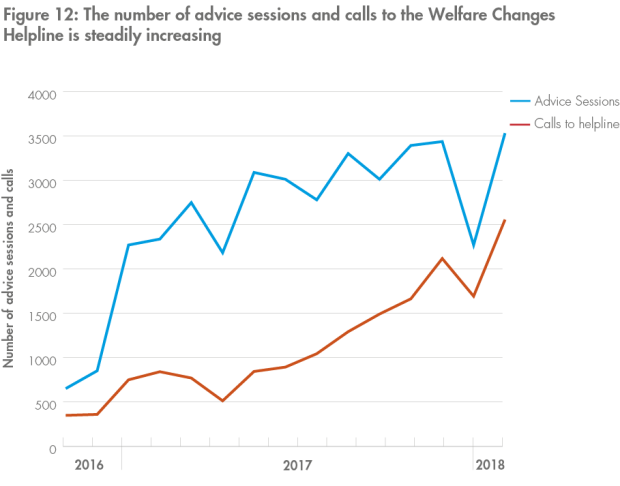

5.1 As noted in Part One (see paragraph 1.11) the Northern Ireland Executive has committed additional funding to independent advisory services. This funding, allocated since September 2016, covers both face-to-face advice services and a centralised free Independent Welfare Changes Helpline. Other support provided to the advice sector includes increasing its digital capacity, training and specialist support.

5.2 Monthly management information submitted by advisory organisations to the Department shows a steady increase in the volume of both advice sessions and calls to the independent helpline (see Figure 12). There has also been a steady increase in the number of helpline callers being referred to the face-to-face advisory service.