List of Abbreviations

AFBI Agri-Food and Biosciences Institute

DAERA Department of Agriculture, Environment and Rural Affairs

DfI Department for Infrastructure

FBIS Farm Business Improvement Scheme Package of measures aimed at improving the competitiveness and sustainability of the farming sector.

IPPC Directive Integrated Pollution Prevention and Control Directive

NIEA Northern Ireland Environment Agency

NMPs Nutrient Management Plans Essential tool for agricultural planning applicants. Nutrient management planning matches nutrient inputs (fertilisers and organic manures) to crop demand.

PSNI Police Service of Northern Ireland

SES Shared Environmental Service A shared service established in 2015 to support councils to carry out Habitats Regulations Assessments for their planning functions.

SNHS Soil Nutrient Health Scheme

SOLACE Society of Local Authority Chief Executives

Key Facts

108 - agricultural planning applications affected

around 3,500 false soil sample results

9 out of 11 councils affected

Executive Summary - Background

1. Certain agricultural practices including intensive farming and the development of anaerobic digestion facilities can have a potentially negative impact on the environment due to the spreading of nutrient rich material on farmland, such as slurry. As a result, there are strict regulatory requirements around establishing or developing the infrastructure associated with these activities. One of these requirements is for applicants to obtain planning permission.

2. In Northern Ireland, the Planning Act (NI) 2011 (the Planning Act) established a two-tier structure for the delivery of planning functions in Northern Ireland (NI). The Department for Infrastructure (DfI) has a central strategic role in the planning system and has responsibility for preparing planning regional policy and legislation, as well as monitoring and reporting on the performance of councils’ delivery of planning functions. In addition, DfI makes planning decisions in respect of a small number of regionally significant and called-in applications. Councils’ role includes determining the vast majority of planning applications, investigating alleged breaches of planning control and determining what action should be taken. DAERA also has an input to the planning system in NI, with its executive agency, the NI Environment Agency (NIEA), being a statutory consultee to the local planning authorities. Relevant bodies’ responsibilities for planning in NI are summarised in Figure 2.

3. The submission of a Nutrient Management Plan (NMP) is required as part of the application to the relevant council for certain agricultural planning permissions. The NMP allows planning applicants to demonstrate that they have assessed the land spreading aspect of their development proposals and have identified an environmentally sustainable outlet or can deal with nutrient rich material, including digestate and manures, without creating environmental harm.

4. NIEA has responsibility for protection of the environment and for promotion of environmentally sustainable development. NIEA fulfils the statutory consultee role in the planning process on behalf of DAERA and provides expert advice and guidance, on areas within its responsibility, to support councils on planning matters.

5. In addition, in cases where a proposal for intensive farming exceeds certain thresholds, as well as obtaining planning permission from the local council, applicants must obtain environmental authorisation in the form of permits or licenses from NIEA. The NMP is again a key consideration in the decision to award the authorisation.

6. A significant element of the NMP is a report on an analysis of the soil upon which the farming activities are to take place. The soil sample analysis results provide information about nutrients in the soil and help to show the extent to which fields can absorb material such as slurry, so that it won’t run off into streams and rivers. Such agricultural run-off has been identified as the main contributing factor for the growth of toxic blue-green algae blooms which significantly affected Lough Neagh and other waterways in Northern Ireland in recent years. The soil samples taken are analysed by a laboratory whose reports are submitted as part of the NMP.

7. NMPs are therefore an essential tool to satisfy environmental regulations and fulfil agricultural planning requirements.

Introduction

8. On 18 October 2022, NIEA first became aware that misrepresented soil sample analysis results had been submitted to them for environmental authorisations and in support of planning applications. NIEA discovered that laboratory reports on soil sample results were either fabricated in their entirety or had been changed prior to submission without the analysing laboratory’s knowledge. By 2 November 2022, NIEA had notified relevant stakeholders including its parent department DAERA, DfI, the NIAO and local councils.

9. One hundred and eight planning applications for agricultural developments in Northern Ireland have been concluded to be affected across nine of the eleven councils, encompassing a total of 3,461 false soil sample results dating back to at least 2015. Appendix 1 shows the number of misrepresented planning applications by council area. Also affected are 19 applications for environmental authorisations and 10 applications for funding under the Farm Business Improvement Scheme (FBIS).

10. In March 2023, a member of the public raised concerns with the NIAO over the handling of this case by NI public bodies. In particular, whilst acknowledging that NIEA had initiated an investigation into the applications for environmental authorisations, the person raising the concern highlighted significant frustration that there appeared to be a lack of ownership or acknowledgment of the fact that there was a separate potential planning fraud issue that required to be investigated. This was despite the relevant bodies being alerted to the issue five months previously from October 2022. In our opinion, the mispresented soil samples should have been recognised by councils as potential planning fraud when notified by NIEA. The person raising the concern advised that despite having engaged in multiple communications with public bodies, there was no ongoing active investigation into potentially fraudulent planning applications associated with this case.

11. The NIAO subsequently began its enquiries into the concerns raised by the member of the public. The NIAO held several meetings and had communications with various officials within NIEA, DfI, councils and SOLACE (Society of Local Authority Chief Executives). This report explores the appropriateness of the response of the relevant NI public bodies, specifically DfI, councils and NIEA, following the discovery of misrepresented soil sample analysis results.

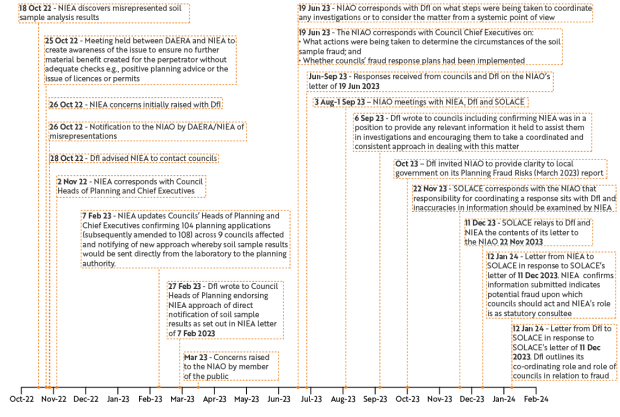

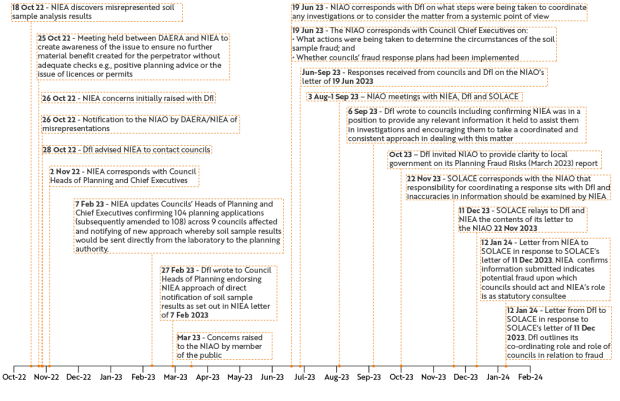

12. From the NIAO enquiries undertaken, it was established that the timeline of events took place as set out in Figure 1 below.

Figure 1: Timeline of Events

Findings and Recommendations

Finding 1

There was a lack of effective collaboration between NI public bodies in response to notification of potential planning fraud.

13. NIEA took proactive steps when it established in October 2022 that some results in soil sample reports it had received had been falsified. NIEA checked with the reporting laboratory the validity of all soil sample reports submitted for planning applications dating back to 2015 and identified that there were 108 misrepresented cases, affecting nine of NI’s eleven councils and encompassing almost 3,500 individual soil sample analyses.

14. In addition to NIEA, the other key stakeholders potentially affected were DAERA, DfI and councils, and NIEA had given a high-level assessment of the position to them by 2 November 2022, only a few weeks after the situation was confirmed by NIEA. NIEA subsequently undertook a review of past and current planning applications and on 7 February 2023, it passed its findings to the local council planning authorities. Each council was given specific information in terms of the number of cases affecting that council. DfI established that it had not been the determining planning authority for any of the 108 cases identified by NIEA.

15. Subsequent to this, collaboration between some of the key planning bodies was extremely poor. We found that there is a lack of clarity around responsibility for undertaking investigations into potential agricultural planning fraud in NI and no organisation appeared to be willing to step forward to ensure a co-ordinated and consistent approach across the planning system.

16. When NIEA wrote to Council Chief Executives and Heads of Planning on 7 February 2023, they provided a listing to each individual council of affected applications in each council area. NIEA told the NIAO that they subsequently made their position very clear that any investigation into the 108 planning applications was outside NIEA’s remit as a statutory consultee and therefore was a matter for councils. This was clarified in a meeting between the NIAO and SOLACE on 1 September 2023 and specifically noted in NIEA’s letter on 12 January 2024 to SOLACE. However, a number of councils advised that prior to these communications they were unaware that NIEA would not be carrying out the investigations on their behalf.

17. What followed the early notifications was a series of communications for over a year between DfI, councils, NIEA and SOLACE, on councils’ behalf, the net result of which was that disagreement remained around which organisation should take responsibility for thoroughly and rigorously investigating the possible planning fraud aspect of this case. For that reason, a number of the planning authorities did not initially launch an investigation into potential planning fraud. In addition, there was insufficient focus on ensuring that a consistent and collaborative approach was adopted across councils. This reluctance to act was despite a concerned member of the public pressing for action and the direct intervention of the NIAO.

18. In a meeting with DfI in August 2023, the NIAO highlighted the beneficial roles that DfI could play in firstly promoting a consistent and co-ordinated approach by all affected councils, and secondly by acting as a point of co-ordination between councils and Police Service of Northern Ireland (PSNI) in relation to any criminal investigations. The response from DfI was that it had worked closely with NIEA to ensure that systemic control measures were put in place (to help prevent this from happening again in the planning application process), communicating with councils and reinforcing messages from NIEA, and encouraging councils, as the responsible planning authorities for their respective applications, to continue to engage with NIEA on this matter for any undetermined applications, as well as those which had previously been determined.

19. In response to the NIAO’s concerns about an inconsistent approach being taken by councils to the potential fraud issue, DfI acknowledged the importance of this matter and re-iterated the role that DfI had played, appropriate to its remit, and that it was content to continue to facilitate or assist with providing information to councils. However, it clarified that with regards to the individual council investigations, this was a matter for those councils which have their own internal governance and fraud arrangements. DfI advised that, whilst it has an oversight role in relation to the planning system in Northern Ireland, its interest in exercising these powers is not to interfere with a council’s right and responsibility to take its own decisions.

20. It is concerning that DfI, the department with responsibility for oversight of the NI planning system, considered it inappropriate to get more directly involved to ensure that all nine affected councils had initiated an investigation into potential planning fraud. Furthermore, it is disappointing that it was unwilling to act as a regional point of co-ordination between the affected councils and PSNI. Taking these actions would have ensured a consistent sector-wide approach. Indeed, DfI instead suggested that the NIAO should itself pursue this objective of securing a consistent, sector-wide approach to the issue and suggested that the NIAO should contact SOLACE in that regard. The NIAO notes that SOLACE is a voluntary organisation with no authority or accountability for oversight of planning matters in NI.

21. The relative perspectives of the various bodies are succinctly summarised in a series of communications between NIEA, DfI and SOLACE (on councils’ behalf) in December 2023 and January 2024 which note the following:

- SOLACE, on behalf of councils, stated that responsibility for co-ordinating a response across the sector should rest with DfI and not with SOLACE, that councils should continue to co-operate with NIEA and should co-operate fully with the PSNI investigation;

- DfI responded that it had written to councils in February 2023 and strongly encouraged affected councils to take a co-ordinated and consistent approach;

- councils stated that any further investigation of inaccuracies in the soil sample reports should be undertaken by NIEA; and

- NIEA replied by reiterating that it is for councils to act upon information that indicates potentially fraudulent planning applications and NIEA’s role is as a statutory consultee.

22. Many of the issues we highlight in this report are not new. In the NIAO report ‘Planning in Northern Ireland’ published in February 2022, the ‘urgent need for improved joined up working between organisations delivering the planning system’ was noted. We recommended that all statutory bodies involved in the planning system should play their part and fully commit to a shared and collaborative approach going forward.

23. The Public Accounts Committee report on Planning in Northern Ireland, published in March 2022, commented as follows:

‘The operation of the planning system is one of the worst examples of silo-working within the public sector…there is fragmentation at all levels – between central and local government, within statutory consultees, amongst the local councils and even the Department [DfI] itself appears to operate in functional silos…there is an urgent need for a radical cultural change in the way in which central and local governments interact. If the planning service is to improve, the Department and councils must start to collaborate as equal partners. This will require a concerted effort from all those involved to work in a more productive way.’

24. Our investigations during the current review found that much more could have been done as regards a shared or collaborative approach to the issues arising from misrepresented soil sampling analysis results, and full commitment to an overarching or co-ordinated response was lacking.

25. Whilst DfI told the NIAO that work is ongoing to implement the actions in the March 2022 PAC report, our findings indicate that the comments made in that report in relation to silo working and fragmentation have still not been adequately addressed.

Finding 2

There was a failure by councils to initiate an investigation of potential planning fraud on a timely basis.

26. Less than half of the nine affected councils confirmed that they had initiated their fraud response plans at the time of responding to the NIAO’s June 2023 letter, despite being alerted to the issue by NIEA on 7 February 2023.

27. It appears that some councils did not initially commence fraud investigations as they believed it was the responsibility of NIEA and it would only be for councils to investigate if there had been a breach of planning conditions.

28. One council, in correspondence in May 2023 to a member of the public who raised concerns, noted that NIEA notifications contained no specific reference to fraud. The correspondence to the councils from NIEA in February 2023 stated that the soil sample results were misrepresented. Therefore, this should have been sufficient for the Council to have considered the matter as potential planning fraud.

29. The NIAO report on Planning Fraud Risks issued in March 2023 noted that ‘the planning system is susceptible to potential fraud and corruption. For example: …planning applicants may make false or misleading statements in planning applications or provide false supporting documentation…’.

30. We therefore find it alarming and a matter of great concern that any council could consider the submission of falsified information in an application for planning permission to be anything other than potential fraud, especially since that exact scenario was highlighted as an example of potential fraud in the NIAO Planning Fraud Risks report in 2023.

31. One council stated that the matter didn’t fall within the remit of its Fraud Policy as there was no evidence to suggest the allegations related to or involved a council employee. This raises a question around the adequacy of this council’s fraud policy if limited to internal fraud, or alternatively to officers’ understanding of the scope of the policy if it is intended to apply more broadly.

Finding 3

Lessons were not learned from a similar case in 2021.

32. In 2021, the Republic of Ireland’s agri-food agency, Teagasc, discovered that a number of poultry farming planning applications in Northern Ireland were supported by falsified documents purporting to come from them. These documents claimed that manure generated by animals housed in new sheds to be erected in NI would be exported to the Republic of Ireland. These documents were vital to satisfy NI’s environmental regulations and therefore critical in ensuring that planning permissions would gain approval.

33. DfI was notified of the issue and subsequently wrote to councils advising them to consider the impact of potentially false Teagasc information in respect of planning decisions granted or in the process of consideration. Councils were also advised that any future letters purportedly from Teagasc were to be checked directly with Teagasc to establish their authenticity.

34. Councils appeared to believe that tracing animal waste exports fell under DAERA’s responsibility for waste and some councils treated the issue only as a breach of planning conditions rather than as potential planning fraud.

35. There are direct comparisons between the 2021 case and the current case. It appears that lessons were not learned from the 2021 incident. Had the advice of DfI to check the authenticity of the Teagasc reports been considered more widely, then the weaknesses exploited in the current case may have been discovered at an earlier point. It is concerning that insufficiently robust action in 2021 may have contributed to a continuation of the issues identified in this report.

Finding 4

Ineffective controls failed to prevent or detect on a timely basis the reporting of false soil analysis results.

36. When the circumstances of the current case came to light, to strengthen controls, NIEA introduced changes in the process for application for planning permission and for environmental authorisations. The changes were endorsed by DfI. They included a requirement for planning applicants to request the testing laboratory to submit the results of their soil sample testing directly to the relevant council. Previously, soil sample analysis results were sent by the analysing laboratory back to the applicant or his/her planning agent who would then submit the results to the planning authorities.

37. However, whilst this was a positive development, there is still a significant control weakness in these new arrangements. Even with the direct submission of soil sample results by the laboratory, there still exists the risk that soil sample results could be manipulated by samples being extracted from locations other than those for which planning permission is being sought.

38. A verification retest of one set of samples was undertaken by NIEA as a pilot. The results of the retest by NIEA showed significantly higher levels of polluting nutrients than those stated on the laboratory reports that had been submitted. Therefore, the current process would not appear to provide adequate assurance that fraudulent results submitted in future will be detected. We are advised that a business case has been developed for additional resource to implement this retest control on a wider scale going forward.

39. The misrepresentation of soil testing results has potential implications for applications for funding to the Farm Business Improvement Scheme (FBIS). DAERA has confirmed that, following discovery of the submission of fraudulent soil analysis results, a pre-payment condition has been placed in the Letter of Offer for successful funding applications and this requires evidence from the planning authority that the claimant’s planning application is still valid at claim stage. Although this is another positive addition, the applicant can simply resubmit new soil sample results and, so long as the planning authority accepts them, they can proceed to apply for the grant, ignoring the fact that potentially fraudulent soil sample reports had initially been submitted.

40. In April 2022, the Soil Nutrient Health Scheme (SNHS) was launched. The SNHS is a four-year, comprehensive regional soil sampling and analysis programme aimed at testing the soil in all 700,000 fields used for farming in NI. The SNHS is being rolled out on a zonal basis, with all 4 zones to be completed by 2026. The scheme has yet to be rolled out to Zones 3 and 4, covering the North East and North West of Northern Ireland. Currently, NIEA does not have access to soil sampling results from the SNHS scheme unless the soil analysis reports are voluntarily included by the applicant in a planning application.

41. The introduction of this scheme, if it is used in planning applications that include a Nutrient Management Plan, could help to reduce the risk of submission of fraudulent soil analysis reports occurring or remaining undetected in the future. We note the uptake for the scheme has been high so far, although its use in future planning applications is to be confirmed.

Finding 5

Potentially more effective arrangements for minimising the impact of excessive levels of nutrients are in place in England.

42. A member of the public raised concerns with NIAO about the current soil sample testing arrangements in Northern Ireland, contending that there are approaches in operation in some situations in other areas of the UK that are more effective than the current NMP approach in NI for dealing with diffuse pollution loading from agricultural practices.

43. An example referenced was the arrangements in place in England to protect designated sites under the Conservation of Habitats and Species Regulations 2017. These arrangements adopt a “nutrient neutrality” approach which ensures that the amount of nutrient pollution entering rivers does not increase because of a new development. Where pollution levels exceed prescribed levels on Habitats Sites, local planning authorities cannot grant permission for new development to take place, unless they can be satisfied that it will not cause further harm to the natural environment (i.e. they are nutrient neutral).

44. The member of the public raising these concerns believes that adopting similar regulations in NI would provide additional protection to the environment.

Recommendations

More Effective Collaboration

45. As recommended in the NIAO February 2022 report on Planning in Northern Ireland, we would reiterate that all statutory bodies involved in the planning system should play their part and fully commit to a shared and collaborative approach going forward. This will necessitate working as equal partners.

46. The NIAO April 2019 report entitled Making Partnerships Work states that ‘central and local government working collaboratively…adds value to public services’. We would recommend that all bodies involved in the planning system in NI review the self-assessment checklist contained in that report and, as a matter of urgency, develop a protocol that clarifies the roles and responsibilities of all stakeholders and ensures effective collaboration. For ease of reference, the checklist has been included in Appendix 2 of this report.

Planning fraud investigations

47. We recommend that councils review the scope of their fraud policies, procedures and response plans to ensure that any alleged submission of misrepresented or falsified information in planning applications is treated as potential fraud and investigated accordingly.

48. Councils should ensure that all officers involved in the planning process understand the scope of their organisation’s fraud policy and response plan, as well as their role in identifying indicators of planning fraud and dealing with allegations of potential fraud should they arise.

49. Whilst we understand that primary responsibility for taking any action under the Planning Act in relation to previously determined applications rests with individual councils, we recommend that DfI should take a more active role in ensuring that a consistent and co-ordinated approach is taken by councils where sector-wide potential planning fraud issues arise in future. This might not necessarily involve DfI leading the investigations, but DfI should as a minimum seek confirmation that each council has formally considered whether the specific circumstances in its council area merit further investigation in accordance with the council’s fraud response plan. Furthermore, it would be appropriate for DfI to seek further explanations from councils in the event that some councils initiate an investigation and others do not.

50. DfI should put arrangements in place to nominate a point of contact to act as a liaison between councils and PSNI as a means of securing an efficient and effective outcome in future cases of sector-wide potential planning fraud.

51. DfI should co-ordinate sector-wide training and awareness sessions as a means of promoting greater consistency in this area.

Learning the lessons

52. We recommend that DfI and councils, with the support of NIEA, should initiate a full review of the circumstances surrounding the 2021 case, together with the current issues highlighted in this report. The aim of this review should be to establish whether there are any further actions required or issues of a similar nature that might as yet remain undiscovered.

53. DfI should ensure that any relevant lessons identified from the above review are disseminated to all planning authorities and it should subsequently seek assurances from councils regarding implementation of measures to ensure that any future misrepresentations in the planning system are discovered and investigated at an early stage.

More effective controls

54. We recommend that independent substantive retesting of reported soil analysis results should be undertaken at a level that will provide adequate assurance over the integrity of all soil analysis reports submitted in future, as part of either agricultural planning applications or agricultural authorisations. We recommend that NIEA should carry out this independent sample testing.

55. We recommend that there is an accelerated roll out of sample testing for Zones 3 and 4 under the Soil Nutrient Health Scheme.

56. We recommend that councils and other public bodies involved in the planning process refamiliarise themselves with the NIAO March 2023 report on Planning Fraud Risks and ensure that, so far as possible, the mitigating controls recommended therein are put in place as a matter of urgency.

Additional environmental protection

57. We recommend that DAERA and DfI jointly review existing planning regulations and determine whether they are sufficient to protect the environment from the impact of diffuse pollution. This review should also consider other potentially more effective approaches such as the “nutrient neutrality” approach adopted for protected Habitats Sites in England.

Conclusions

58. Subsequent to the initial contact from DAERA in October 2022 in relation to potential fraud, the NIAO was alerted by a member of the public to the fact that a number of public bodies were reluctant to take ownership of the need to investigate whether issues discovered by NIEA constituted potential planning fraud. Frustration was expressed that one public body seemed to be passing responsibility to another and as a result, potential planning fraud was going unchecked. More importantly, the concern was raised that ongoing damage was potentially being done to the environment as a result of a lack of compliance with planning regulations.

59. The NIAO undertook a review and found that collaboration was poor between a number of the bodies involved, with a lack of clarity about specific roles and responsibilities as regards investigation of potential planning permission fraud for agricultural developments. We discovered evidence that some of the issues we investigated were not new and that lessons appeared not to have been learned from a number of relevant reports previously issued by the NIAO and the NI Assembly’s Public Accounts Committee.

60. We noted that some positive measures were taken on discovery of the issue in order to improve the controls in operation around the planning permission application process. However, we identified that there are still inherent weaknesses in the current arrangements that require to be addressed. We are somewhat assured that there are arrangements in place to address some of these weaknesses, although an acceleration of the implementation timelines would be beneficial. We have made a number of recommendations in our report to assist in further addressing the issues raised.

61. We were disappointed that more proactive steps were not taken, despite the concerns being raised by a member of the public and the direct and repeated intervention of the NIAO. It is essential that the planning system commands public confidence and in our view that confidence has been undermined as a result of the response to this issue by the NI public sector generally.

Part One: Background and Introduction

Planning responsibilities in Northern Ireland

1.1 In Northern Ireland, responsibility for planning is shared between DfI and the eleven local councils as planning authorities.

1.2 The respective roles of DfI and local government district councils in the Northern Ireland planning system are set out in legislation and reflect the intention of the NI Executive to create a two-tier planning system in 2015, transferring the majority of planning functions to the newly formed councils. Local councils have responsibility for a significant number of planning functions and are autonomous political authorities, outside the direct control of DfI.

1.3 This report focuses mainly on the potential planning fraud aspect as a result of the submission of misrepresented information in support of planning permission applications to councils. DfI has confirmed to the NIAO that it was not the determining authority for any of the planning permission decisions referred to in this report. The determining authority was one of the councils in each of the cases. Councils are responsible for investigating alleged fraud in respect of any of their functions, under their own anti-fraud and governance policies, procedures and response plans.

1.4 Consideration of any action under the Planning Act in respect of previously determined planning applications which may have been affected by misrepresented information, is a matter for the planning authority which took the decision(s) in the first instance, in this case, the councils.

1.5 Relevant powers available under the Planning Act in such circumstances are discretionary and a matter for the relevant planning authority, if considered ‘expedient’. The use of such powers is therefore a consideration by the relevant planning authority, taking into account the individual circumstances of each case, having regard to the local development plan and any other material considerations including the proper planning of the area within its district, amenity interests and the wider public interest generally.

1.6 Notwithstanding the above, DfI, in its oversight role, works to support local planning authorities in addressing systemic issues and seeks to promote consistency in approach in line with regional objectives and policies.

1.7 DAERA’s planning responsibilities include advice, with NIEA, an Executive Agency within DAERA, being a statutory consultee to the local planning authorities.

1.8 Figure 2 summarises the responsibilities of each of these bodies.

Figure 2: Responsibilities for planning in Northern Ireland

Local Government

- Development planning – creating a plan which will set out a clear vision of how the council area should look in the future by deciding what type and scale of development should be encouraged and where it should be located.

- Development management – determining the vast majority of planning applications.

- Planning enforcement – investigating alleged breaches of planning control and determining what action should be taken.

DAERA

- Environmental advice for planning.

- Development management.

- Responses to development proposals where there is potential for impacts on the natural and marine environments and fisheries interests.

DFI

- Oversight and performance monitoring.

- Planning legislation.

- Regional planning and policy.

- Determination of regionally significant and ‘called in’ planning applications.

- Planning guidance.

NIEA

- Working towards a fully compliant regulated industry.

- Delivering freshwater environment at ‘good status’.

- Tackling waste sector crime.

- Supporting good habitat, earth science and landscape quality and enhancing species abundance and diversity.

- Promotion of environmentally sustainable development, infrastructure and access to quality green and blue spaces.

Background

1.9 There are strict regulatory requirements around establishing or developing the infrastructure associated with intense farming activities and anaerobic digestion facilities. One of these requirements is for applicants to obtain planning permission from their local council. In addition, in cases where a proposal for intensive farming, for example of pigs or poultry, exceeds certain thresholds, as well as obtaining planning permission from the local council, applicants must obtain environmental authorisations from NIEA.

1.10 These agricultural planning applications require the submission of supporting information that demonstrates the environmental impacts of the development or proposal from the spreading of nutrient rich material, such as slurry, on farmland. For each field (no larger than 4 hectares) where digestate, manure, slurry or litter is to be applied, a Nutrient Management Plan (NMP) is required. DAERA publishes guidance on the information required in an NMP, full detail of which can be found on their website.

1.11 NIEA began requesting NMPs in 2015 to assist in the consideration of planning applications and environmental authorisations, and their potential impact on the environment. NMPs can be subject to review by NIEA and councils. NIEA fulfils the statutory consultee role in the planning process on behalf of DAERA and provides expert advice and guidance on areas within its responsibility, to support councils on planning matters. However, NIEA informed us that whilst it provides advice, any regulatory or enforcement action in relation to planning applications is the responsibility of the local council planning authorities.

1.12 An NMP should include soil sample analysis results that are less than four years old. Soil samples are taken by either the applicant or their agent on the applicant’s behalf and then sent to a laboratory for analysis. Analysis results are presented on the laboratory’s headed paper, using the laboratory reporting template, and are signed off by an employee from the laboratory.

1.13 Until recently, the process was that the results were sent back to the applicant or their agent. A copy of the laboratory results was then submitted by the applicant or their agent to the planning authority (the relevant council) as part of the planning permission process and to NIEA if environmental authorisations were required. The return of the laboratory results to the applicant or agent was a flaw in the overall system of control and, as will be highlighted later in this report, one that was exploited.

1.14 NMPs which include these soil sample analyses are therefore an essential tool to satisfy environmental regulations and fulfil agricultural planning requirements. They allow planning applicants to demonstrate that they have assessed the land spreading element of their development proposals and have identified an environmentally sustainable outlet or can deal with nutrient rich material including digestate and manures, without harming the environment. Failure to do so means the planning applicant has failed to demonstrate an assessment of the environmental impact of their development.

Introduction

1.15 According to information published on the DAERA website in 2018, only 18 per cent of soils analysed in Northern Ireland are at optimum fertility for pH, Phosphorus and Potassium. In October 2022, an NIEA officer became suspicious of multiple soil samples with notably low Phosphorus results. The NIEA officer contacted the analysing laboratory in England to cross check soil sample records and discovered multiple misrepresentations of soil sample analysis results included in NMPs, submitted in support of agricultural planning applications and environmental authorisations for anaerobic digester plants and agricultural livestock houses. In many cases, the purported analysing laboratory had no record of the sample reference numbers presented within the NMPs. NIEA discovered that results had either been fabricated in their entirety or had been changed without the laboratory’s knowledge.

1.16 NIEA has identified 108 planning applications for agricultural developments in Northern Ireland (both determined and those currently under consideration) that have been supported by misrepresented and, according to NIEA following examination, false and potentially fraudulent soil sample analyses. These relate to 8 anaerobic digester plant applications and 100 agricultural livestock house applications. A total of 3,461 false soil samples have been found to have been submitted in support of these planning applications dating back to 2015, when NIEA introduced the requirement for an NMP.

1.17 A number of the planning applications determined in 2015 had been submitted in 2012, 2013 and 2014 but were still awaiting a decision in 2015, and therefore required an NMP. Appendix 1 sets out the number of misrepresented farm planning applications by council area.

1.18 Also identified were misrepresentations in 19 applications for environmental authorisations; 14 of these were on hold and five had already been granted. NIEA subsequently launched an investigation into alleged fraudulent applications for environmental authorisations relating to these cases. Based upon NIEA’s review of the affected planning applications and environmental authorisations, the cumulative total of manures proposed to be spread in Northern Ireland was approximately 306,000 tonnes per annum.

1.19 Ten current applications for funding under the Farm Business Improvement Scheme (FBIS) were also affected. Successful applications under this Scheme have a pre-payment condition inserted into their letters of offer to ensure continued compliance with planning is evidenced at claim stage. This requires evidence from the planning authority that their planning application still holds at claim stage. DAERA confirmed that none of these applicants have received funding and it was not aware of any other planning applications impacted by misrepresented soil sample analysis results which have previously been in receipt of EU funding under the FBIS scheme.

1.20 In March 2023, concerns were raised with the NIAO by a member of the public over the handling of this case by NI public bodies. In particular, the person raising the concern acknowledged that NIEA had initiated an investigation into the fraudulent application for environmental authorisations but highlighted significant frustration that despite being alerted to the issue from October 2022, five months later there still appeared to be a lack of ownership or acknowledgment of the fact that there was a separate potential planning fraud issue that required to be investigated. The person raising the concern advised that as a result, at the point the matter was raised with the NIAO, despite having engaged in multiple communications with public bodies, there was no ongoing active investigation into potentially fraudulent planning applications associated with this case. However, the mispresented soil samples should have been recognised by councils as potential planning fraud when notified by NIEA.

1.21 The NIAO subsequently began its enquiries into the concerns raised by the member of the public. The NIAO had a number of meetings and communications with various officials within NIEA, DfI, councils and SOLACE (Society of Local Authority Chief Executives). From the NIAO enquiries, it was established that the timeline of events took place as set out in Figure 3. This report explores the appropriateness of the response of a number of NI public bodies, specifically DfI, councils and NIEA, following the discovery of misrepresented soil sample analysis results.

Part Two: Responses from NI Public Bodies

2.1 Following the discovery that soil sample results were misrepresented, the sequence of events was as shown in Figure 3 below.

Figure 3: Timeline of Events

2.2 In the following paragraphs we set out in detail the responses provided by NIEA, DfI and councils.

NIEA response

2.3 DAERA has a role in providing ‘environmental advice for planning’ and its Executive Agency, NIEA, is responsible for promoting ‘environmentally sustainable development’.

2.4 NIEA told the NIAO that it was not directly involved in all 108 planning applications as their responsibility extends only to environmental authorisations, i.e. the granting of licences or permits in certain cases such as under the Integrated Pollution Prevention and Control (IPPC) Directive. This applies to many industrial sectors, including the intensive farming of pigs and poultry. Under the IPPC Directive, intensive pig and poultry units over specified thresholds must obtain a permit to operate. The thresholds are as follows:

- Poultry: 40,000 bird places; and

- Pigs: 750 sows or 2,000 production pigs over 30kg.

NIEA’s responsibility therefore includes issuing licences or permits as part of larger agricultural planning applications where required. It also operates as a statutory consultee in the planning process.

2.5 NIEA initially raised concerns with its parent Department, DAERA, following the discovery of the misrepresentations on 18 October 2022. Following a meeting on 25 October 2022 between NIEA and DAERA, NIEA raised concerns with DfI the following day and corresponded with Council Heads of Planning and Chief Executives on 2 November 2022 to make them aware of the issue. NIEA also brought the matter to the attention of interested parties including the Shared Environmental Service (SES), established to support councils across Northern Ireland to carry out their habitats regulations assessments for their planning functions, and the Planning Appeals Commission, an independent body which deals with a range of land use planning issues and related matters.

2.6 NIEA also alerted DAERA Governance Branch who then informed the NIAO and the Department of Finance Group Fraud Investigation Service.

2.7 Having alerted Council Heads of Planning to this issue in November 2022, NIEA then undertook detailed preliminary checking with the laboratory that had purportedly provided the soil sample analysis reports. The purpose was to check the validity of the laboratory reports provided, to be able to provide councils with specific details of any misrepresented soil sample reports submitted as part of planning applications to those councils.

2.8 NIEA contacted each council individually on 7 February 2023 confirming the number of planning applications supported by false soil sample results for that council. NIEA told the NIAO that it later advised councils clearly that any investigation into the 108 planning applications was outside NIEA’s remit as a statutory consultee and therefore was a matter for councils. This was clarified in a meeting between the NIAO and SOLACE on 1 September 2023 and specifically noted in NIEA’s letter on 12 January 2024 to SOLACE. As a statutory consultee to the planning process, NIEA’s responsibility is to provide planning authorities with advice and guidance.

2.9 NIEA informed the NIAO that it has launched criminal investigations into misrepresented soil sample analysis reports that have been submitted to it in support of environmental authorisation applications. Application for environmental authorisations is an entirely separate process from planning applications. The investigations into environmental authorisation applications do not extend to the 108 affected planning applications as NIEA has no investigative, regulatory or enforcement powers in relation to the planning process. The legislation which NIEA applies, in relation to environmental authorisations, includes the offence of submitting false or misleading statements or false entries. These offences are accompanied by significant penalties, including fines and potential imprisonment.

2.10 NIEA confirmed that responsibility for investigation of potential planning fraud rests with local councils. NIEA advised that the first step of any council investigation would be to seek information from NIEA on each individual case within the council area. NIEA would then provide councils with information held on each of the planning cases. This would provide each council with case specific evidence that false soil sample analysis results have been submitted in support of each of the identified planning applications. NIEA advised that councils should then decide whether this information indicated that a criminal offence had potentially been committed under the Fraud Act and initiate actions in accordance with their fraud response plans. This could then result in councils referring the matter to the PSNI.

2.11 On 11 December 2023, SOLACE, the Society of Local Authority Chief Executives, included in correspondence to NIEA (and DfI), its letter to the NIAO from 22 November 2023 which noted that inaccuracies in information should be examined by NIEA, and proposed that a meeting be organised between itself, DfI and SOLACE. On 12 January 2024, NIEA in response wrote to SOLACE, confirming that its examination of the soil sample analysis reports submitted in support of 108 planning applications, across 9 council areas, resulted in the conclusion that the submitted information was false and would indicate potential fraud. NIEA confirmed that, while it viewed the information on the Planning Portal in its role as statutory consultee, it was not the recipient of the information. As such, it had carried out preliminary checks with the laboratories and had alerted councils to the specific issues affecting each of them individually in February 2023. This was to enable councils to implement their governance and anti-fraud policies and procedures. NIEA noted that it would continue to support councils on the matter upon request, and in its role as a statutory consultee. NIEA referred to the Permanent Secretaries Group / SOLACE meeting in mid-February 2024, at which DAERA was represented, and invited SOLACE to raise this as an agenda item. NIEA advised that it also offered to attend a meeting with SOLACE and DfI on the issue.

2.12 NIEA stated that there were 14 live applications for environmental authorisations (licences and permits) which were affected by misrepresented soil sample analysis reports and NIEA placed determination of these on hold, pending further investigation. For the five environmental authorisations already granted (waste management exemptions for land spreading of digestate), which have been identified by NIEA as containing misrepresentations, Departmental Solicitor’s Office advice has been sought on the appropriate action to be taken.

2.13 The NIAO has also been advised that an NIEA Investigation Team has been established within its Environmental Crime Unit and criminal investigations are ongoing, focused on the misrepresented results submitted in support of applications for environmental licences and permits.

2.14 An NIEA Oversight Group has been established on this issue, which includes representatives from all its affected areas, including NIEA Environmental Crime Unit investigators.

DfI response

2.15 On 26 October 2022, NIEA notified concerns relating to the misrepresented soil samples to DfI as the Department responsible for strategic oversight and performance monitoring of the planning system in NI. DfI reviewed all 108 applications and established that it was not the determining authority for any of the cases identified by NIEA. DfI subsequently advised NIEA to contact all relevant councils directly to bring the issue to their attention as the determining planning authorities.

2.16 Although none of the applications were managed by DfI as the determining planning authority (all managed by councils), the NIAO wrote to DfI on 19 June 2023 to establish what steps were being taken to co-ordinate council investigations or to consider the matter from a systemic point of view. DfI advised us as follows:

‘Whilst DfI has an oversight role in relation to the planning system in Northern Ireland, its interest in exercising these powers is not to interfere with a council’s right and responsibility to take its own decisions, but for the purpose of considering the exercise of its strategic planning functions and the achievement of regional planning objectives. The Department is not responsible for investigating allegations of fraud, irregularity and misconduct within councils. Councils have responsibility for their own governance and audit arrangements as autonomous organisations.’

2.17 DfI asked for the findings to be shared from the NIAO’s request to councils of the same date on action taken and regarding the implementation of council fraud response plans.

2.18 DfI highlighted that its co-ordinating role and actions to date can be summarised as follows:

- In late October 2022 NIEA advised DfI that it had recently become aware that fabricated soil sample analysis results had been submitted in support of planning applications for anaerobic digester plants and agricultural livestock houses going back a number of years. DfI carried out a desk-top review confirming that it was not the decision-maker in any of these applications and that all the impacted cases were within local government (council) jurisdiction.

- The then Chief Planner immediately responded to NIEA advising that it should urgently write to Heads of Planning in relevant councils bringing this to their attention and to re-consult NIEA on any relevant undetermined applications. Councils were also advised that they may wish to investigate previously determined planning applications.

- DfI wrote again to all councils on 27 February 2023 to endorse the additional control measures in the development management process advocated by NIEA (the statutory nature conservation advisor and consultee in relation to this issue). The Department also encouraged councils (as the responsible planning authorities for their respective applications) to continue to engage with NIEA for any undetermined applications, as well as those which may have previously been determined (in order to decide if there was a material impact on any planning permission granted and consider any appropriate action). The Department advised that it was for the local planning authorities to consider and decide what action to take in relation to previously determined applications, depending on the individual circumstances of each case (and taking advice from NIEA, Shared Environmental Service etc.).

- DfI wrote to councils on 6 September 2023 confirming, following further engagement with the NIAO and NIEA, that NIEA was in a position to provide any relevant information it held in relation to the identified cases to assist the councils in any investigations they may be taking, or considering taking, in relation to cases of alleged fraudulent activity or breach of planning control. The letter also reinforced the advice in its previous letter that any relevant application being made to a council and any associated NMP should meet the revised controls proposed by NIEA. It also encouraged the affected councils to take, in so far as possible and appropriate, a coordinated and consistent approach to dealing with this matter in relation to governance, fraud policies and procedures as well as in terms of the exercise of any powers under the Planning Act regarding previously determined applications.

- In October 2023, following further engagement with the councils on this issue at the Strategic Planning Group (SPG), DfI informed the NIAO that local government required clarity in relation to its published report on Planning Fraud Risks (March 2023) and invited it to attend the next SPG meeting in January 2024 to discuss issues around fraud in planning. The NIAO accepted the invitation to attend the January SPG meeting to address the general issue of planning fraud.

2.19 On 12 January 2024 DfI wrote to SOLACE outlining the communication and co-ordination role DfI had performed in relation to this matter; and also set out the importance of differentiating between the issues of potential fraud and potential implications for a council’s planning decisions.

2.20 The NIAO met with DfI on 16 August 2023 and highlighted the importance of a consistent and co-ordinated approach across the sector. Discussion highlighted the fact that councils would require the support of PSNI to pursue any potential criminal investigations through the courts. The NIAO suggested that DfI could play an important role in ensuring PSNI was clear that this was a province-wide issue affecting nine of our eleven council areas, thereby increasing the likelihood of PSNI prioritisation of this issue for a police investigation. The NIAO also suggested that DfI was ideally placed to ensure consistency and co-ordination across councils as well as between councils and PSNI.

2.21 DfI advised the NIAO that it was not DfI’s role to undertake the actions suggested but DfI agreed to write to councils encouraging a co-ordinated approach. DfI suggested that if the NIAO wished to promote a co-ordinated approach, it might wish to take the matter up with the Society of Local Authority Chief Executives (SOLACE). The NIAO notes that SOLACE is a group established to share ideas and best practice across the eleven councils in NI. However, SOLACE carries no status as regards oversight of the actions of its members in relation to planning matters.

2.22 We find DfI’s responses to be disappointing. DfI has a strategic role in relation to oversight of the planning system in NI and as such carries the authority and gravitas to encourage and support a consistent, collaborative and efficient approach across the planning system. We believe an opportunity was missed by DfI in this regard.

Local Government/Councils’ response

2.23 On 2 November 2022, councils were notified of NIEA’s initial concerns regarding ‘irregularities in soil sample analysis results included in Nutrient Management Plans’. NIEA recommended re-consultation with both NIEA and the Shared Environmental Service (SES) on any un-determined planning ‘applications for Anaerobic Digester Plants or agricultural livestock houses, involving the land spreading of digestate or manures’. It was advised that some applications would have already been determined.

2.24 On 7 February 2023, NIEA wrote to councils confirming the number of affected applications across nine councils where they had confirmation from the testing laboratory that soil sample analysis reports had been falsified. Two of the eleven councils were unaffected, Belfast City Council as well as Ards and North Down Borough Council.

2.25 Councils’ responsibilities include ‘planning enforcement – investigating alleged breaches of planning control and determining what action should be taken’. The NIAO wrote to councils on 19 June 2023 to ascertain what action was being taken by them in relation to the concerns highlighted by NIEA and whether individual fraud response plans had been implemented.

2.26 It is clear from the replies that the nine affected councils responded differently when they were alerted to this issue by NIEA and treated the matter with varying levels of seriousness.

2.27 Several councils confirmed to the NIAO in their initial responses that investigations or reviews had commenced, but no further detail was given. In determined cases, enforcement was stated to be underway or being considered. Planning conditions were being reviewed by some councils to consider enforcement and for live cases, some councils referred to the new requirement issued by NIEA for direct submission of soil sample results, resubmission of soil sample results and some cases being held.

2.28 A recurring theme highlighted by councils’ initial responses was that there was no clear direction from NIEA and several councils commented that NIEA findings had not been shared with them. NIEA however highlighted in their letter to SOLACE on 12 January 2024 that they had alerted councils to the issue and informed them of the 108 planning applications in several pieces of correspondence since discovery of the issue on 18 October 2022. NIEA first raised this with Council Heads of Planning and Chief Executives in correspondence dated 2 November 2022. A list of affected applications identified in each council area was provided directly to individual councils as a council specific annex to NIEA’s 7 February 2023 letter.

2.29 Some councils noted that they were liaising with NIEA on the matter. One council wrote to NIEA to confirm whether NIEA considered fraudulent activity had occurred and if it had been reported to PSNI. NIEA advised that council in July 2023 that it had initiated a criminal investigation but that it was limited to those results submitted in support of environmental authorisation applications, as this is within NIEA’s legislative remit. NIEA confirmed that the scope of its investigation did not include planning applications and highlighted that any investigation into breaches of planning legislation, or potential planning fraud, was a matter primarily for councils as the planning authorities.

2.30 However, in response to the NIAO’s June 2023 letter seeking confirmation of their action, only four councils confirmed that they had initiated their fraud response plans at that time.

2.31 At the time of compiling this report, only five councils had requested detailed information from NIEA (Armagh City, Banbridge and Craigavon Borough Council; Antrim and Newtownabbey Borough Council; Causeway Coast and Glens Borough Council; Derry City and Strabane District Council; and Mid Ulster District Council). Four of these five councils (Antrim and Newtownabbey Borough Council; Causeway Coast and Glens Borough Council; Derry City and Strabane District Council and Mid Ulster District Council) plus one further council (Mid and East Antrim Borough Council) had made referrals to the PSNI and these are being dealt with by the PSNI’s Economic Crime Branch.

2.32 We find the lack of action by some affected councils to be concerning, even after prompting by the NIAO. It appears that some councils failed to instigate adequate investigations into the potential planning frauds, believing that NIEA were investigating and would act.

2.33 SOLACE acts as the professional voice for local government. However, as noted earlier in this report, it carries no status as regards oversight of the actions of its members in relation to planning matters. Following a meeting with the NIAO on 1 September 2023, SOLACE issued a letter of behalf of councils to the NIAO on 22 November 2023. SOLACE advised as follows:

‘It seems obvious that the responsibility for co-ordinating a response to a Northern Ireland wide issue impacting the vast majority of councils should lie with the body with responsibility for the oversight of planning, namely DfI. It is impossible for councils at this stage, in their role as planning authorities, to determine whether any inaccuracies in information are as a result of human error, contamination or deliberate or reckless behaviour. This is very much a matter which the NIEA would need to examine and consider, and councils would have to rely on their expertise in this regard.’

2.34 Further to this, SOLACE wrote to DfI and NIEA on 11 December 2023 to confirm that they had advised the NIAO that the responsibility for co-ordinating a response to the matter sat with DfI and that any inaccuracies in the information held should be examined by NIEA. SOLACE proposed a meeting in early 2024 between DfI, NIEA and themselves to have a collaborative discussion and agree the next steps.

Part Three: Findings and Recommendations

Finding 1

There was a lack of effective collaboration between NI public bodies in response to notification of potential planning fraud.

3.1 NIEA responded positively when its staff initially established in October 2022 that some results in the soil sample reports it had received had been falsified. It quickly informed its parent Department, DAERA, and realising that this issue could also have a significant impact on planning permission applications, the following day it alerted DfI, given that DfI is the government department in NI with overall oversight responsibility for planning. Subsequently, DfI advised NIEA to alert local councils, given councils’ role as the primary planning authorities.

3.2 Accordingly, on 2 November 2022, NIEA wrote to all Council Chief Executives and Heads of Planning and informed them of its finding that misrepresented soil sample results had been submitted to councils as part of planning permission applications. NIEA advised that it would update councils in due course with further information in this regard.

3.3 NIEA then proceeded to check with the reporting laboratory the validity of all soil sample reports submitted for planning applications dating back to 2015. NIEA ultimately identified that there were 108 misrepresented cases, affecting nine of NI’s eleven councils and encompassing almost 3,500 individual soil sample analyses. On 7 February 2023, NIEA wrote to each individual council, outlining the number of planning applications affected in each council area.

3.4 Therefore, NIEA took proactive steps when this matter came to light. All the key stakeholders had been alerted to the position by NIEA within a few weeks of it being confirmed. NIEA undertook a review of past and current planning applications and each council was given specific information in terms of the number of cases affecting that council on 7 February 2023. DfI established at this point that it had not been a determining planning authority for any of the cases identified by NIEA.

3.5 Subsequent to this, collaboration between some of the key planning bodies was extremely poor.

3.6 When NIEA wrote to Council Chief Executives and Heads of Planning on 7 February 2023, it provided a listing to each individual council of affected applications in each council area.

3.7 In March 2023, a member of the public raised a concern with NIAO. The person raising the concern told us that when an update was sought from each of the nine councils on what action was being taken to investigate the potential planning fraud, the response was that it was a matter for NIEA to take forward. The person raising the concern told us that, having contacted NIEA, it confirmed that NIEA has no remit in relation to planning enforcement and that any planning fraud investigation is the responsibility of local councils. The member of the public raising the concern expressed dismay that none of the NI public bodies seemed to be interested in tackling this significant potential planning fraud issue.

3.8 In June 2023, the NIAO formally wrote to Council Chief Executives to establish what actions councils were taking to determine the circumstances around the cases of potential planning fraud as highlighted by NIEA.

3.9 Over the summer of 2023, the NIAO received a variety of responses from councils. Whilst there were some differences in approach, none of the councils had taken any meaningful steps to proactively and robustly investigate the potential that they had received falsified soil sample reports as part of planning permission applications.

3.10 NIEA told the NIAO that they made their position very clear that any investigation into the 108 planning applications was outside NIEA’s remit as a statutory consultee and therefore was a matter for councils. This was clarified in a meeting between the NIAO and SOLACE on 1 September 2023. This was also specifically noted in NIEA’s letter on 12 January 2024 to SOLACE. However, a number of councils claim that prior to these communications they were unaware that NIEA would not be carrying out the investigations on their behalf. Initially therefore, there appeared to be a lack of clarity around who was responsible for undertaking the investigations into potential agricultural planning fraud.

3.11 The NIAO also wrote to DfI in June 2023 to ascertain what actions DfI was taking to co-ordinate any council investigations or to consider the matter from a systemic point of view. The NIAO followed this up in a meeting with DfI in August 2023 where the NIAO highlighted the beneficial roles that DfI could play in firstly ensuring a consistent and co-ordinated approach by all affected councils, and secondly by acting as a point of co-ordination between councils and PSNI in relation to any criminal investigations.

3.12 The response from DfI was that it was not its responsibility to undertake a co-ordinating role across councils in relation to local government planning fraud investigations and suggested that this role would be more appropriate for the NIAO and we should contact SOLACE in relation to securing such a role. DfI contended that it had played an appropriate oversight role and highlighted that, whilst DfI has an oversight role in relation to the planning system in Northern Ireland, its interest in exercising these powers is not to interfere with a council’s right and responsibility to take its own decisions.

3.13 It is concerning that the department with responsibility for oversight of the NI planning system considered that it was not its role to get more directly involved to ensure a consistent sector-wide response. In fact, DfI stated that it was for the NIAO to pursue the possibility of a co-ordinating role with SOLACE in relation to councils’ response to potential planning fraud across NI. The NIAO notes that SOLACE is a voluntary organisation with no authority or accountability for oversight of planning matters in NI.

3.14 Communication between NIEA, DfI and SOLACE (on councils’ behalf) in December 2023 and January 2024 notes the following:

- SOLACE, on behalf of councils, stated that responsibility for co-ordinating a response across the sector should rest with DfI and not with SOLACE and councils should continue to cooperate with NIEA and should cooperate fully with the PSNI investigation.

- DfI responded that it had written to councils in February 2023 and strongly encouraged affected councils to take a co-ordinated and consistent approach.

- Councils stated that any further investigation of inaccuracies in the soil sample reports should be undertaken by NIEA.

- NIEA replied by reiterating that it is for councils to act upon information that indicates potentially fraudulent planning applications and NIEA’s role is as a statutory consultee.

3.15 We found that there is a lack of clarity around responsibility for undertaking investigation into potential agricultural planning fraud in NI and none of the organisations appears to be willing to step forward to ensure a co-ordinated and consistent approach across the planning system.

3.16 An NIAO report published in February 2022 entitled Planning in Northern Ireland noted the ‘urgent need for improved joined up working between organisations delivering the planning system’. It commented on the identification of ‘significant silo working within the planning system’ which is ‘not currently operating as a single, joined-up system’ and warned that the ‘system doesn’t deliver for…the environment’.

3.17 The Public Accounts Committee report on Planning in Northern Ireland published in March 2022, commented as follows

‘The operation of the planning system is one of the worst examples of silo-working within the public sector…there is fragmentation at all levels – between central and local government, within statutory consultees, amongst the local councils and even the Department [DfI] itself appears to operate in functional silos…there is an urgent need for a radical cultural change in the way in which central and local governments interact. If the planning service is to improve, the Department and councils must start to collaborate as equal partners. This will require a concerted effort from all those involved to work in a more productive way.’

3.18 Whilst DfI told the NIAO that work to implement the actions in the March 2022 PAC report is ongoing, the findings from our current review would indicate that the comments made in that report in relation to silo working and fragmentation have still not been adequately addressed.

Recommendations

3.19 As recommended in the NIAO February 2022 report on Planning in Northern Ireland, we would reiterate that all statutory bodies involved in the planning system should play their part and fully commit to a shared and collaborative approach going forward. This will necessitate working as equal partners.

3.20 The NIAO April 2019 report entitled Making Partnerships Work states that ‘central and local government working collaboratively…adds value to public services’. We would recommend that all bodies involved in the planning system in NI review the self-assessment checklist contained in that report and develop a protocol that clarifies the roles and responsibilities of all stakeholders and ensures effective collaboration in relation to planning matters. For ease of reference, the checklist has been included in Appendix 2.

Finding 2

There was a failure by councils to initiate an investigation of potential planning fraud on a timely basis.

3.21 Less than half of the nine affected councils confirmed that they had initiated their fraud response plans at the time of responding to the NIAO’s June 2023 letter. It appears that some councils did not initially commence fraud investigations as they believed it was the responsibility of NIEA and it would only be for councils to investigate if there had been a breach of planning conditions.

3.22 SOLACE in its letter to the NIAO on 22 November 2023 confirmed that ‘councils should continue to co-operate with NIEA, and if NIEA’s investigation reveals evidence of suspected fraud, this is a matter we would expect the NIEA to report to the police…councils do not have the experience, resources or statutory powers to investigate or prosecute fraudulent behaviour and would ordinarily, as a matter of course, defer to the police in this regard.’

3.23 One council in its initial response to the NIAO found there to be no breach of planning conditions attached to the permission. Council correspondence in May 2023 to a member of the public who raised concerns with the council noted that NIEA notifications contained no specific reference to fraud. The correspondence to the councils from NIEA in February 2023 stated that the soil sample results were misrepresented and therefore this should have been sufficient for the Council to have considered the matter as potential planning fraud.

3.24 One council stated that the matter didn’t fall within the remit of its Fraud Policy as there was no evidence to suggest the allegations related to or involved a council employee. This raises a question around the adequacy of this council’s fraud policy if limited to internal fraud, or alternatively to officers’ understanding of the scope of the policy if it is intended to apply more broadly.

3.25 The NIAO report on Planning Fraud Risks issued in March 2023 notes that ‘the planning system is susceptible to potential fraud and corruption. For example: …planning applicants may make false or misleading statements in planning applications or provide false supporting documentation…’.

3.26 We find it alarming and a matter of great concern that some councils did not consider the submission of falsified information in an application for planning permission to be potential fraud, especially since that exact scenario was highlighted as an example of potential fraud in the NIAO Planning Fraud Risks report in 2023.

Recommendations

3.27 We recommend that councils review the scope of their fraud policies, procedures and response plans to ensure that any alleged submission of misrepresented or falsified information in planning applications is treated as potential fraud and investigated accordingly.

3.28 Councils should ensure that all officers involved in the planning process understand the scope of their organisation’s fraud policy and response plan, as well as their role in identifying indicators of planning fraud and dealing with allegations of potential fraud should they arise.

3.29 Whilst we understand that primary responsibility for taking any action under the Planning Act in relation to previously determined applications rests with individual councils, we recommend that DfI should take a more active role in ensuring that a consistent and co-ordinated approach is taken by councils where sector-wide potential planning fraud issues arise in future. This might not necessarily involve DfI leading the investigations, but DfI should as a minimum seek confirmation that each council has formally considered whether the specific circumstances in its council area merit further investigation under the council’s fraud response plan. Furthermore, it would be appropriate for DfI to seek further explanations from councils in the event that some councils initiate an investigation and others do not.

3.30 DfI should put arrangements in place to nominate a point of contact to act as a liaison between councils and PSNI as a means of securing an efficient and effective outcome in future cases of sector-wide potential planning fraud.

3.31 DfI should co-ordinate sector-wide training and awareness sessions as a means of promoting greater consistency in this area.

Finding 3

Lessons were not learned from a similar case in 2021.

3.32 Following an alert by a member of the public, an internal investigation was launched in 2021 by Teagasc (the Republic of Ireland’s agri-food agency) into several poultry farm planning applications from Northern Ireland. The investigation found that in 23 cases, documents purporting to be issued on Teagasc’s behalf were either completely falsified or altered without its knowledge or consent.

3.33 Animal waste produces harmful emissions such as ammonia. Due to the already high levels of this gas in Northern Ireland, the majority of which is linked to agriculture (97% according to DAERA’s website), farmers have increasingly looked for other ways to dispose of poultry litter, such as the export of waste to farmers in the Republic of Ireland. Evidence such as documents from Teagasc, which claim that manure generated by animals housed in new sheds erected in NI would be exported to the Republic of Ireland, are vital to satisfy NI’s environmental regulations and therefore ensure that planning permissions can gain approval.

3.34 DAERA and NIEA were alerted to the Teagasc investigation in 2021, and they notified DfI, who in turn wrote to councils advising them to consider the impact of potentially false Teagasc information in respect of planning decisions granted or in the process of consideration. Councils were also advised that any future letters purportedly from Teagasc were to be checked directly with Teagasc to establish their authenticity.

3.35 Councils appeared to believe that tracing animal waste exports fell under DAERA’s responsibility for waste and some councils treated the issue only as a breach of planning conditions rather than as potential planning fraud.

3.36 It is concerning that insufficiently robust action by public bodies in 2021 may have contributed to a continuation of the issues identified in this report. It appears that lessons were not learned from the 2021 incident, and a similar failure to take responsibility and lack of collaboration following discovery of the current case is noted. Had appropriate action been taken at the time of the 2021 discovery, the issue may have been resolved at an earlier point, thereby protecting the environment from further damage.

Recommendations

3.37 We recommend that DfI and councils, with the support of NIEA, should initiate a full review of the circumstances surrounding the 2021 case, together with the current issues highlighted in this report. The aim of this review should be to establish whether there are any further actions required or issues of a similar nature that might as yet remain undiscovered.

3.38 DfI should ensure that any relevant lessons identified from the above review are disseminated to all planning authorities and it should subsequently seek assurances from councils regarding implementation of measures to ensure that any future misrepresentations in the planning system are discovered and investigated at an early stage.

Finding 4

Ineffective controls failed to prevent or detect on a timely basis the reporting of false soil analysis results.