Executive Summary

1. Within the public sector context there are a number of organisations that operate to a greater or lesser extent at arm’s length from ministers and their sponsoring departments. These specific bodies are generally referred to as Non-departmental Public Bodies (NDPBs) and are managed by a board.

2. The main purpose of the board is to provide effective leadership, direction, support and guidance to the organisation and to ensure that the policies and priorities of the ministers and the Northern Ireland Executive are implemented.

3. The importance of effective boards in the current climate of change cannot be emphasised enough; they are a key component to the successful operation of an organisation through their dual role of support and scrutiny.

4. The most effective boards are:

- proactive;

- a driving force in achieving delivery against an organisation’s mission, vision, values and objectives, especially by embedding corporate values and behaviours and by creating the right culture;

- alert to risk and changes in the organisation’s operating environment; and

- firmly focused on strategic issues.

5. There are currently over 1,000 board positions within the Northern Ireland public sector and there are many individuals who aspire to become board members. This guide should be useful for current and potential board members, as well as departmental staff administering public appointments, ministers, senior civil servants and chief executives. The content is primarily targeted at NDPBs. Many of the general points and good practices outlined are, however, equally valid for departments, health trusts and other governing bodies, such as colleges and school governors.

6. The intention of this guide is to offer ways to improve and enhance board effectiveness drawing from various sources of best practice, research and suggestions from focus groups facilitated by the NIAO. The guide is not prescriptive or definitive but rather a quick and easy way to access some clear and concise advice.

7. A board needs to be discerning when considering the application of this guide i.e. what is practical and proportionate in the context of the organisation’s role, remit, size and complexity.

What this guide covers;

- Building a Board

- Developing a Board

- Roles, Responsibilities and Relationships

- Operating a Board

- Evaluating a Board

- Board Pack (sample documents)

Chapter One: Building a Board

What is the optimal composition of a board?

1.1 Composition matters when it comes to the effective and competent performance of a board. A board’s performance will benefit from appointing individuals with the requisite knowledge, skills and expertise.

1.2 Perhaps the most common question people ask about boards is ‘How big should it be?’ The response to this question is ‘It depends.’ The most common size of an NDPB board is eight, with an average size of 11, within a range of 2 to 23.

1.3 There is no actual number of board members to which all organisations should aspire. There is no one-size-fits all. There have been suggestions that the optimal board size as far as decision making is concerned is somewhere between five and eight members. But it is not that simple.

1.4 The expectation is that the number of board members should be proportionate to the size and complexity of the organisation. For a small to medium sized organisation with relatively straightforward strategic aims, consideration should be given to an optimal board size of five to eight. But for larger more complex organisations, board size may grow. A board in this context should think about limiting size to somewhere in the vicinity of 15 members.

1.5 In other words when building a board, it should be sufficiently large to carry out its responsibilities, without unnecessarily limiting its effectiveness with excessive numbers that inhibit individual engagement and involvement for board members. In the context of an NDPB, the sponsor department and minister are the key drivers in building the board, but consultation between the chairperson of the board and chief executive ensures size and composition are informed by the board’s assessment of itself.

1.6 The board of an NDPB, in conjunction with the sponsor department, needs to carefully examine its purpose as set by the minister and how this impacts on the precise size. Factors to include are:

- Functional requirements – in terms of professional expertise, does the board have members to help with strategic priorities or to bring needed expertise to the board e.g. financial expertise to handle audit and risk assurance committee responsibilities?

- Diversity requirements – in terms of age, ethnicity or gender, does the board have the right variety of viewpoints and dialogue on critical issues? Northern Ireland Executive has set targets to achieve gender equality in public appointments.

- Representational requirements – in terms of the stakeholders in the organisation, does the board include local government representation, community representation etc?As with diversity, the question is what representation is needed to help the board fully understand the issues and options it is facing.

- Regulatory requirements - in terms of membership requirements designated in legislation, the board is expected to comply.

1.7 In relation to regulatory requirements, if the size of a board becomes difficult to manage, the legislation should be subject to review by the parent department, in conjunction with the minister, to ensure it remains fit for purpose. Consideration should be given to having legislation which is less prescriptive as to size, to allow greater flexibility.

1.8 The minister and the sponsor department, in consultation with the board, need to determine the right size. Before settling on a final number they should consider two pertinent questions:

- Have we designed a board of sufficient size that can carry out all the requisite functions, including committee work, without overburdening the individual board members?

- Have we designed a board that will allow all board members to stay personally engaged and interested in the responsible activities of the board?

If the answer to both these questions is ‘YES’, this would suggest the size of the board is probably right.

1.9 Where a large board is being developed, or is already in place but with no clear rationale for its size, a simple tool that might help to identify potentially unproductive members is the use of a board overview matrix. Such a process is also of benefit during succession planning and gap analysis. A copy of the matrix is attached at Annex 1.

1.10 Whilst it is important a board contains members with the necessary requirements in terms of functional skills and experience, the significance of personal attributes cannot be ignored or underplayed. Certain types of people will benefit the operation and decision making of a deliberative board. Thought needs to be given to how such attributes can be assessed as part of the appointments process and how they can be developed throughout the member’s term of office.

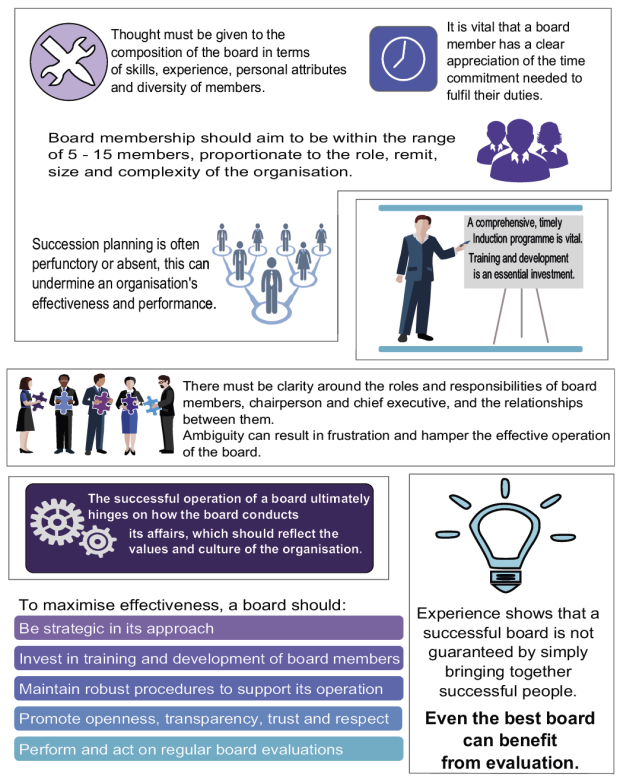

Figure 1: Attributes of an Effective Board Member

Appointment Process

1.11 The appointment process, grounded in the merit principle, is paramount when building a successful, sustainable board. The appointment process needs to attract and recruit a sufficiently diverse pool of people to serve on boards.

1.12 The Commissioner for Public Appointments for Northern Ireland has been a strong advocate for greater representation/diversity on boards. Her aim is to promote board opportunities to a wider audience and to help make it easier for individuals to apply to become a board member.

1.13 The Code of Practice for Ministerial Appointments in Northern Ireland has recently been updated to ensure ministers are made aware of the details of the gender breakdown of the current membership of the board to which they are appointing. Ministers will receive this information at the outset of the competition and again when they receive the list of suitable candidates before an appointment is made.

1.14 The appointing department must also make the minister aware of the agreed NI Executive targets on diversity in public appointments. These targets only relate to gender but this is a step towards putting representation/diversity at the fore of the appointment process. The Chairs Forum has advised that it is dedicated to ensuring these targets are achieved by working closely with the Commissioner for Public Appointments for Northern Ireland and with voluntary and community based organisations to enhance diversity on boards.

1.15 Good practice should be built on an open and equitable appointment process. Open dialogue and interfacing between the minister, permanent secretary and chairperson and chief executive of the NDPB should help provide clarity and understanding and prompt voluntary action in advance of any further changes to the Commissioner's Code of Practice. This will help boards operating in complex environments to grow in efficiency and effectiveness.

How much time does it take to be a board member?

1.16 Time commitment will vary from board to board, but the description for the post should include a realistic approximation of the time commitment expected e.g. number of hours for reviewing materials, attending board and other committee meetings (as appropriate) and any other tasks. The time commitment should be reiterated in the appointment letter. It is essential that board members fully appreciate the time commitment before accepting a position.

1.17 Board members must be able to give the requisite time to each board upon which they sit. It is vital that both the board member and the organisation keep this under review and take immediate action should the time commitment not be invested. Action could be a quick discussion with the person concerned, a note recorded on the performance record of the board member with recommendations for improvement or in the most extreme cases, the board member could be asked to resign from the board.

1.18 Some board members will serve on more than one board which raises questions about the supply of independent board members. There were 1,372 board positions in Northern Ireland as at 31 March 2015 and these were filled by 1,160 individuals. Of these 1,160 individuals, 15 per cent (179) indicated membership of more than one board. The maximum number of positions held by any one individual was four.

To Pay or Not to Pay board remuneration?

1.19 Some board members receive a remuneration package for their time and in appreciation of the increasing level of responsibility they have in relation to their duty to exercise diligence, care and skill. In other boards, no remuneration is given except for the reimbursement of travel and expenses.

1.20 The history of public sector organisations in Northern Ireland clearly records a significant and important contribution by unpaid board members. Reward has traditionally been regarded as one’s social commitment or desire to give back something to wider society. This is particularly true in the context of a charitable organisation where trustees volunteer their time freely and without an expectation of payment in return. Approximately half of NDPBs in Northern Ireland do not remunerate board members.

1.21 It is important that public organisations make their remuneration and reimbursement policy clear at the appointment stage and include details in the terms of appointment. Nonetheless applicants need to be aware that a voluntary position carries no less responsibility. Whether board members are paid or not, they should expect to be held to account in terms of their governance roles, responsibilities and performance.

1.22 When deciding whether to remunerate or not, the following factors should be kept in mind:

- the challenge of appointing and retaining appropriate members;

- the time commitment of being a member of a board and also a sub committee member; and

- the level of intellectual capacity and capability that is required to deal with the complexities and interrelationships associated with the organisation and stakeholders.

What is good Succession Planning?

1.23 Succession planning is the process of identifying and developing potential future leaders . Best practice dictates that this should be applied to boards. There is currently no governance requirement to ‘comply or explain’ with regard to this principle, which is why succession planning and reporting on it is often perfunctory or absent. The lack of a succession plan can undermine an organisation’s effectiveness and performance.

1.24 The board should be satisfied that, in conjunction with the sponsor department, there is in place a plan for orderly succession of board appointments. It should be a ‘live document’, to be updated when required but at least reviewed annually by the board as part of its evaluation process.

1.25 For example, when a new board is established, thought should be given to staggering the longevity of appointments to ensure they do not end at the same time, or alternatively putting in place a plan to renew appointments by varying lengths i.e. to ensure a balance between continuity and renewal of board members. The Commissioner for Public Appointments reports that ‘failure to properly plan for board succession is a chronic problem with some departments and results in the undesirable practice of multiple extensions to tenure.‘

Figure 2: Writing your Succession Plan - simple practical considerations

WHEN

- does a new member need to be in place? Identify when positions are due to become vacant. Ideally changes to the board will be incremental to allow for consistency, stability and knowledge transfer. In practice this means that if you have a number of appointments ending at the same time, consider staggering lengths of subsequent appointment so there is a step change in future.

- do we need to initiate an appointment process? Understand how long an appointment process takes – this gives you a timeframe to commence an appointment with a view to filling a position in time to allow for a full induction, and potentially some ‘shadowing’, so the new member can ‘hit the ground running’.

WHO

- do we need on the board? Complete a skills and diversity analysis on a member by member basis, to identify the exact needs the board has for a future board member. The analysis should feed into a person specification (skill set, experience, behavioral traits) to be used to develop and refine the documentation used in the appointment process, rather than requiring a generic list of skills.

HOW

- do we make sure we get the best pool of suitable applicants? Use the analysis to inform and refine appointment documentation and design the appointment process. This might involve innovative ways of advertising positions to ensure a diverse range of potential applicants are reached, for example utilising social media. It requires that appointing authorities ensure they are accessing relevant networks particularly those related specifically to underrepresented groups.

Building Boards for the Future

1.26 Everyone recognises the need for a steady stream of members to service new and existing boards but positive action is needed to provide ‘a diverse and sustainable pool of capable board members which is reflective of society’. To address this consideration should be given to the concept of the Boardroom Apprentice. Being a board member requires certain skills, knowledge, experience and understanding. In many cases, lack of experience prevents young people, females, people from different social economic or ethnic groups etc. from applying for such a position. How do such individuals who aspire to make an effective contribution in the boardroom get the necessary experience and ‘know-how’ to make this a reality?

1.27 One solution suggested is the creation of an apprenticeship-style opportunity which facilitates those who are interested to serve on a board for a period of 12 months in a non-voting capacity, in addition to a six month training programme and the added support of a ‘board buddy’.

1.28 Another solution suggested is seeking experience in voluntary/charity organisations, school governing bodies, etc. where demand is generally higher than availability of people.

1.29 The Commissioner for Public Appointments advises that a number of such initiatives are being set up and can be accessed through the Office of the Commissioner for Public Appointments.

Chapter Two: Developing a Board

2.1 Boards are not static. An effective board is dynamic and fluid and having new members is critical to the ongoing success of most boards. However, without effective training and development members can become frustrated and disaffected. Appropriate training and development of board members can help make an average board into an exceptional board.

2.2 Board members come to the boardroom with varying degrees of previous training, knowledge, skills, experience and understanding of the body itself. It is therefore important to use gap analysis to identify any potential training or development needs. For new members it is imperative that comprehensive induction is provided at the outset and is subsequently supported by a training and development programme.

2.3 It is the role of the chairperson, in conjunction with the sponsor department and assisted by the board secretariat, to ensure inductions take place and individual training needs assessments are prepared. Such assessments should be a compulsory part of a board member’s annual evaluation (sooner for a new member or if deemed necessary) and inform a board-wide training and development programme. Such a programme must be flexible and subject to revision and updating as needs evolve.

Induction – Does it provide new board members with the information they need to get started?

2.4 A strong induction programme is beneficial as it eases transition into a board, and ensures that board members have a good understanding of the body, its environment and their individual role, resulting in members who are effective from the outset. In particular the relationship between a public board and the minister and its sponsor department is one not always clearly understood by board members and therefore clear explanation should be given and discussion held on this subject.

2.5 It is important that no assumptions are made based on a member’s prior experience or posts. All new members should receive a standard induction to ensure they all begin with at least the same base level of knowledge. Specific individual needs can be identified during an initial meeting with the chairperson and added to the induction programme or included in the training and development programme. It is crucial that induction is seen as important and does not become a tick box exercise. It should also be delivered on a timely basis.

2.6 In order to speed up the learning curve, boards should provide in advance an induction (welcome) pack. This means that new board members are being prepared to ‘hit the ground running’. Before a new board member attends their first board meeting, they should receive a detailed induction pack which contains information about the body, the workings of the board, expectations of an individual board member, and other vital information, for example, the code of conduct. It should also focus on the strategic plan for the body as it is crucial for a new board member to be familiar with the organisation’s mission, vision, values and major objectives.

2.7 Provision of an induction pack should be followed up with face-to-face induction training. This should incorporate:

- meetings with the chairperson of the board and other key staff (e.g. chief executive/director of finance); and

- attendance and observation at a board meeting.

In addition it is useful to allocate a longer standing board member as a mentor for each new board member, as a point of contact and support.

Having an induction programme in advance enables the new board member to fully participate in the first meeting with self-assurance and confidence. A specimen induction programme is at Annex 2.

2.8 Induction of a new chairperson requires specific consultation with the sponsor department and the minister. Good practice, as outlined above, can be read across from the board member to the chairperson.

Figure 3: Induction – Key Questions

WHEN

- should an induction be carried out? As soon as possible after appointment, and preferably prior to the new board member’s first official board meeting.

WHO

- should organise the induction? The chairperson, in consultation with the sponsor department, should organise the induction, with the assistance of the board secretariat.

- should be involved in the induction? The new board member should have a chance to speak to key people as part of the induction process - the chairperson, chief executive and finance director as a minimum.

WHAT

- should be included in the induction programme? Start with a comprehensive induction pack, which provides a full picture of the organisation and its environment. Tailor the face-to-face induction programme to incorporate any additional needs (based on a board member’s discussion with the chairperson) into the induction, or include them in any subsequent training and development programme for all board members. (see Annex 2)

HOW

- do you ensure that the induction process is fit for purpose? After a few board meetings, the chairperson should meet with the new member, ensure they have settled into their role, and seek feedback on the usefulness of induction.

Don’t take knowledge for granted.

Ongoing Training and Development

2.9 Training and development of the board is an essential investment. Creating an ongoing plan will help ensure that board members know what they are accountable for, to whom they are accountable and most importantly how to be accountable.

2.10 Training and development is about getting board members eager, excited and energised to learn what it really means to be an effective member of a board and how to bring about successful and meaningful results.

2.11 Training and development of the board can have resource implications and in tight financial environments can be a focus for budgetary cuts, especially when board members do not believe they need training or development. Whilst recognising the skills and experience that members have and bring to the table, often such board members simply ‘do not know what they do not know’.

2.12 Lack of continuous professional development is often highlighted as a weakness within boards. Training and development of members should not end with induction; induction should be the start of an ongoing process.

Case Study

A mid-size organisation budgeted an excessive amount of money and resources for training of board members. An expensive training programme was initiated without regard to assessed needs. The significant investment generated considerably less than the expected results, and the members expressed critical dissatisfaction with the training. Members requested advice on a better approach.

The issue was addressed by asking members to evaluate their strengths and limitations and establish a benchmark of their knowledge, experience, skills etc. On the basis of this analysis, a multi-phased training and development programme was implemented. Within six months to a year the members, the board reported, increased overall effectiveness resulting from greater focus, energy and results.

2.13 When funding is tight, more innovative approaches to training and development need to be taken. Examples of such approaches might include:

- looking for opportunities to benefit from economies of scale in procurement of external training. This could be through collaboration or joint commissioning with other bodies either across government (such as the Chief Executive Forum’s leadership training initiative) or across sectors (such as health or education);

- accessing relevant but free webinars or seminars (in particular, workshops held by the sponsor department or Department of Finance);

- looking for networking opportunities with other public sector bodies, for example, participation in the Chairs Forum;

- presentations from staff on emerging issues or operational changes as an item on the board agenda;

- arranging to meet outside of formal board meetings to discuss and debate issues e.g. in workshops;

- inclusion of board members on training courses planned for staff;

- shadowing board members prior to taking up a position;

- rotating responsibilities (for sub committees etc.) between all members; [This will not only provide an opportunity for development and deeper understanding but will aid with the retention of knowledge and experience when a member’s term comes to an end.] and

- accessing expertise from within departments or other government bodies through informal means.

Who is responsible for Training and Development?

2.14 It is the responsibility of the chairperson, in conjunction with the sponsor department to:

- identify the priority learning and development needs of members;

- collate the learning and development needs of members and, in conjunction with the board secretariat, put in place a plan for delivery;

- ensure members attend relevant statutory, mandatory, induction and update training;

- ensure training needs assessments are completed during the appraisal cycle; and

- evaluate the effectiveness of learning and development activities with members.

2.15 It is the responsibility of the board member to:

- identify their own training and development needs in line with their role as a board member;

- attend and participate in statutory, mandatory, induction and update training;

- apply their learning to the boardroom;

- prepare for and participate in the appraisal process by identifying their own learning and development needs;

- maintain and develop the necessary knowledge and skills for their role; and

- contribute to the evaluation of learning and development activities.

2.16 At least annually, as part of an appraisal process, the chairperson of the board should consider each member’s current level of involvement and contribution and discuss any areas for improvement, coupled with any training and development opportunities that could be provided to enhance effectiveness in their role.

2.17 The most successful boards explicitly invest significant time in developing board members to help maximise their effectiveness, both through training and personal development.

Chapter Three: Roles, Responsibilities and Relationships

3.1 There are primarily two different board types operating in Northern Ireland public sector organisations. This chapter concentrates on the type of board indicative of NDPBs which is composed totally of non-executive directors. A non-executive director is a person who is considered to be independent as he/she is not part of the management of the organisation. Reference is made later in the chapter to another type of board which is indicative of health trusts and government departments. Such a board is made up of both executive and non-executive members. Both types of board come with their challenges, but regardless of type, the role of the board is to provide effective leadership, strategic direction, support, constructive challenge and guidance to the organisation.

3.2 In the context of an NDPB there must be clarity around the roles of a board member, the chairperson and chief executive and their associated responsibilities. These should be set out in the organisation’s Management Statement and Financial Memorandum (MSFM), which has been put in place by the sponsor department. Any uncertainty should be addressed as ambiguity can cause frustration and consequently hamper the effective operation of the board. Furthermore, where an organisation is also constituted as a company, consideration must be given to the extra duties and legal requirements this places on its board members. The MSFM is a live document and should fully reflect current roles and responsibilities. If there is any misunderstanding of roles, or the board feels there is a mismatch between the responsibilities assigned to the board and its actual authority, the chairperson should meet with the sponsor department to explore areas where greater clarity would be beneficial and if required, the MSFM updated accordingly.

3.3 The operating framework or terms of reference for the board should also provide further detail on roles and responsibilities. These documents should align with the MSFM.

3.4 Boards frequently have members who are nominated representatives of different stakeholder groups. This can give rise to members using the board as a platform to champion their own interests. It is critical that nominated representatives act solely in the interests of the board. Advocacy can help inspire decision making but an effective board member must exhibit corporate responsibility and remember they have a wide and unified role to play.

3.5 Healthy debate and challenge is more likely to be achieved if board communication is underpinned by a spirit of trust and professional respect. Consensus can be a good thing, but using consensus to avoid conflict, or encouraging all members to consistently express similar views or consider few alternative views, does not encourage constructive debate and does not give rise to an effective board dynamic. The development of constructive relations, especially between the chairperson and chief executive and board members and senior executive officers, is a critical aspect of good governance.

3.6 ‘You need an atmosphere in the boardroom that’s conducive to open and honest discussion. There must be a collective willingness to confront the difficult issues and management must be able to talk openly about their challenges as well as their triumphs’. Robert Swannell, (Chairman of Marks and Spencer).

3.7 Sometimes board members feel uncomfortable with a decision as it is being made but decide to remain silent. In some cases it is fine to let the meeting roll on, but in other cases it is an indication of a board that may later be described as asleep at the wheel. An underlying but too-common reason is that there is an implicit feeling that questioning the staff (or the majority) is being distrustful or not acting as a team member.

3.8 If you find yourself experiencing such thoughts, take a few seconds to think it through. There are more choices than simply keeping quiet or being disruptive. Be sure you take the board’s decisions as seriously as the organisation needs them to be taken, and doing so will sometimes mean being clearer or more robust than is ordinarily necessary. The importance of constructive challenge as part of board effectiveness cannot be emphasised enough.

3.9 Regardless of the nature of board debate, the board should nonetheless aim to retain a unified voice and display corporate responsibility in any internal or external communication following deliberation. The ability to be unified enables board members to feel confident in the decision making process and satisfied their views have been considered.

3.10 Board members occupy a position of trust and their standards of action and behaviour must be exemplary. Board members should always act in the interests of the body. They should not act in their own interest or pursue personal agendas.

3.11 The notion that board members have an objective view and unbiased judgement underlies the importance ascribed to having a board at the forefront of an organisation’s governance framework.

The Chairperson

3.12 The chairperson is the cornerstone of the board and is expected to bring valuable credentials and a personal commitment to the role. Frequently the chairperson is perceived to be the single biggest determinant of a board’s effectiveness. He or she has the primary role in determining the focus of the board, setting the tone for discussions and influencing the composition of the board. Care and attention should therefore be taken when appointing the chairperson.

Figure 4: Key characteristics of a good chairperson

- The right motivation – the chairperson needs to be clearly and unambiguously focussed on achieving the success of the public sector organisation.

- Commitment and engagement – the chairperson needs to devote the necessary time and energy. Being a successful chairperson is much more than preparing for and running board meetings. A chairperson needs to maintain regular dialogue with the chief executive, have a presence in the organisation and connect with the executives, keep non-executives abreast of developments and cultivate external relationships which provide useful links for the organisation. However, they need to be mindful of overstepping the boundaries of their role and becoming too involved in the day-to- day operation of the organisation.

- Well developed interpersonal skills – being a chairperson is about leadership not dominance. The chairperson needs to be able to build and motivate the board, forge an effective working relationship with the chief executive that is simultaneously collaborative and challenging, and adapt their style to reflect the needs of different situations. Being a chairperson is as much about emotional intelligence as intellectual.

- Effective operation of the board – the chairperson has a key responsibility for influencing board composition, setting the right agenda (i.e. needs to ensure the board spends its time on the right issues), managing the board to enable collaborative and robust discussion of the issues and summarising and synthesising the strands of discussion to determine a conclusion and an agreed set of actions. [A number of these aspects are developed further later in the guide].

3.13 Those who sit on boards emphasise the importance of the chairperson’s role. It is a demanding and difficult role that requires skills that are different in many respects from those that underpin a successful executive career. Great chief executives do not necessarily make good chairpersons, and equally the best chairpersons may not have been chief executives themselves. Some board members suggest you need to understand the business but not necessarily come from the sector, and skills are much more important than previous industry expertise. This is not to say that knowledge of the sector etc. is not useful or desirable.

The Chief Executive

3.14 Alongside a skilled chairperson, it is critical that an organisation is lead by a chief executive who sees the board as a valuable resource and acts as a conduit for effective engagement between the board and the executive team. It is very important for the chief executive to work constructively and openly with the board. If the board is not confident it is being kept fully informed about the organisation, this must be addressed by the chairperson as the board cannot be effective from a position of partial knowledge, particularly the chairperson.

3.15 It is important the chairperson and chief executive can agree their respective roles and responsibilities and how they will work together in practice, as understanding and respecting each other’s role and responsibilities is the bedrock of a good relationship.

3.16 Linked to this is the need for boards to define their priorities for the year ahead and how they intend to fulfil them. The best boards are adept at staying focussed on what matters. This is not to suggest that plans should be rigid but it helps to progress strategic thinking and execution by the board, as opposed to straying into the operational responsibilities of the chief executive.

Figure 5: Key points for consideration by the Chief Executive (see footnote 14)

- The chief executive needs to embrace the role of the board – the chief executive needs to view the board as a source of experience and insight rather than a nuisance to be managed. The chief executive should listen to the board and not seek to dominate discussions. The chief executive should not attempt to stage manage discussions or reduce the role of the board to rubber-stamping.

- Open and constructive dialogue – the chief executive needs to be a role model to other executive colleagues by exhibiting open support for the chairperson and the non-executive members and the contribution they make. This means the chief executive recognises the legitimacy of all questions and accepts input as constructive challenge, not criticism. The chief executive needs to have the self-confidence to bring questions to the board for discussion and direction. In addition providing the right information and professional board papers as well as keeping the board abreast of pertinent issues, is vital for good communication and effective decision making.

- Engagement outside meetings – open and transparent informal interactions are critical in building trust, forging relationships and giving board members a richer and deeper feel for the organisation. Chief executives should aim to maximise and arrange such contact. Informal contact should be easy and unfettered.

Board Secretariat

3.17 The board secretariat has an important role in supporting the board and has the potential to shape its effectiveness. Some holders of the role focus merely on supporting the efficient operation of the board and related processes such as organising meetings, issuing papers, taking the minutes etc. The best secretariat however plays a critical role as an invaluable source of counsel and advice not only to the chairperson but also other board members. He or she can be an important sounding mechanism on issues that are emerging and a second set of eyes and ears on the business and its dynamics. (see footnote 14)

3.18 The secretariat, supported by the chief executive, should help ensure the papers provided to the board are of sufficient quality and address the key strategic issues facing the organisation, although ultimately the board members must be satisfied with the quality of information provided.

3.19 Just as any member of the board can have a dominating or negative impact, the same is true of the board secretary. The board must consider carefully who should fulfil this role. He or she should have the necessary boardroom experience and confidence in terms of processes and procedures but with the essential component of independence. Where possible, they need to be independent of management and work directly for the interests of the board. Frequently, however, the secretary will have a dual role due to their employment with the organisation. The staff member fulfilling the board secretary role must therefore have the freedom to perform this role without undue pressure or control from management. Clarity of his or her role and responsibilities is therefore paramount.

The Minister

3.20 The minister in charge of the department is responsible and answerable to the Assembly for the exercise of the powers on which the administration of that department depends. He or she has a duty to the Assembly to account, and to be held to account, for all the policies, decisions and actions of the department, including its NDPBs. Communication between the board and the minister are normally through the chairperson of the board. The relationship between the NDPB board and the minister is therefore critical. To quote from a particular chairperson ‘the chairperson of the board needs to build an open and trusting partnership with the minister. The foundations of such a relationship should start as soon as the new minister or chairperson is appointed.

3.21 It is essential that time is taken to establish and develop this relationship. Early engagement and regular scheduled meetings between the minister and the chairperson are of particular importance, with agreed agenda items for such meetings. Where possible the chief executive from the NDPB should also attend to help disentangle operational issues from the strategic issues. These meetings also provide an opportunity to discuss with the minister any issues within the NDPB of potential public interest.

Other Type of Board Structure

3.22 A board which includes executive and non-executive members operates within the health sector and government departments. This type of board structure can enable a more substantive discussion to take place during board meetings and may help to prevent non-executive members from intruding on management issues.

3.23 It can, in some cases, take time before both executive and non-executive members coming on to the individual board become fully integrated. There is anecdotal evidence of a feeling of ‘us’ and ‘them’ between executive and non-executive members. This dynamic can be particularly challenging and needs to be carefully managed. Detailed at Figure 6 are some points worthy of consideration by a board’s executive directors.

Figure 6: Key points for consideration by a Board’s Executive Director

Conflicts of Interest – an executive director may find the demands of their day job put them in an uncomfortable position with their role as a member of the board. For example, tough decisions such as cutting programme expenditure may be difficult for an executive who manages the relevant operations. The board can, however, still receive the benefit of the face-to-face discussions, but the conflicted executive should exempt themselves from any decision in this area (See Footnote 18). In relation to other sensitive areas such as the review of executive directors’ performance, discussions should be held in closed sessions whereby executives are excluded. Conducting an annual review of the executive team is imperative in meeting the board’s duty of oversight and for confirming that the board and executive agree on the objectives and priorities of the organisation. The practice of a non-executive meeting at least once a year, without the executive team present, provides a useful forum for raising any such issues.

Presence of Chief Executive – other executive directors who attend as board members may feel less able to debate. The chairperson should be alert to any signs such as the stifling of debate and reluctance to engage in rigorous discussion.

Dilution of responsibility - all board members have a duty to add value. The presence of executive members does not dilute this responsibility. Executive members should not be expected to have all the answers in terms of the issues and priorities of the organisation. Collaborative working and engagement by all board members is essential to board effectiveness and decision making.

Departmental Boards

3.24 A departmental board is advisory in that it is intended to support the permanent secretary and the senior management team. It brings together senior executives with non-executives (generally two non-executives from outside the organisation), and is chaired by the permanent secretary. Even though the composition of the departmental board is primarily made up of executive members, the presence of non-executives should help the department to operate in a business-like manner and ensure executive members are supported and challenged in the way the department is run and how it delivers public services.

3.25 The departmental board does not, however, decide policy or exercise the power of the minister. The department's policy is decided by the minister on advice from officials. The remit of the board is to advise on the operational implications and effectiveness of policy proposals.

3.26 Figure 7 below provides a summary of the key roles and responsibilities in relation to board effectiveness, presented in the context of an NDPB.

Figure 7: Roles Responsibilities – What is expected of me?

The table below sets out the main responsibilities of each role, presented in the context of an NDPB. Generally the board’s role is to develop strategies and policies and monitor performance, and the executive’s role is to implement these and provide advice when required.

|

Key Areas of Work |

Minister / Department |

Chairperson |

Board Members |

Chief Executive |

|---|---|---|---|---|

|

Appointment |

Minister has ultimate responsibility for appointing members to the board. |

Advises sponsor department and minister regarding appointments, taking account of succession planning. |

||

|

Strategy |

Minister sets overall policy and defines expected outcomes. |

Leads on formulating strategy for delivery of objectives. |

Formulate strategy for delivery of objectives. |

Assists in development of strategy:

|

|

Corporate & Business Plans |

Final approval provided by the sponsor department. |

Approval of corporate and business plans prior to submission for approval by sponsor department. |

Drafts corporate and business plans based on board agreed strategy. |

|

|

Performance |

Receives information from the board via the chairperson and provides feedback as necessary. |

The point of contact between the minister, sponsor department and the board. Ensures that board communications with the sponsor department or minister are accurate and on a timely basis. Ensures that communications from the sponsor department or minister to the board are fed back. |

Constructively challenge the executive team on all aspects of performance, including target setting.

|

Delivers effective performance by:

|

|

Board Information |

Sets/agrees the agenda for each meeting. Liaises with board secretary to ensure that appropriate information is received on a timely basis. Ensures any issues regarding the provision of information are resolved to the board’s satisfaction. |

Ensure that they receive regular financial information and other information of strategic importance. Challenge executive to satisfy board information requirements. |

Provision of comprehensive papers for each board meeting as per the agenda and as requested at any other time via the board secretary. |

|

|

Decision Making |

Sponsor department or Minister approves decisions which are outside the delegated authority of the board. |

Ensures the board, when reaching decisions, takes proper account of guidance provided by the minister and sponsor department and of relevant delegated authorities. Ensures that minutes of meetings of the board accurately record decisions taken and views of individual members. Confirms that board decisions have been effectively implemented. |

Collectively take decisions after thorough and constructive debate. Note that a sense of corporacy means that, whilst disagreement can be noted in the minutes, once a decision has been made, all board members should normally support the collective decision or resign if appropriate. Consider and agree minutes. |

Implements decisions made by the board. Takes action in line with Managing Public Money NI should the board decide on a course of action which would infringe the requirements of propriety or regularity or does not present prudent or economical administration or efficiency or effectiveness. |

|

Board Discussions |

Ensures discussions remain focused on strategy and performance and are not distracted by inappropriate detail or operational issues. Sets the style and tone of the meeting, to promote open discussion and constructive debate. Ensures that the full agenda is dealt with, within the allocated time and a conclusion is reached in respect of each agenda item, with action points noted, where appropriate. |

Contribute to thorough and constructive debate. Listen to the views of others. |

Ensures that financial and non-financial considerations are taken into account by the board to inform board discussions. Advises the board on relevant guidance from Department of Finance (DoF) or the sponsor department. |

|

|

Relationships |

Sponsor department should be open to engagement and provide support when required. |

Promotes effective relationships with and between board members, executive and the sponsor department. Builds a constructive working relationship with the chief executive. Builds rapport and engages with the minister and departmental officials. |

Formulate positive working relationships with other board members. A culture of trust should be fostered between members. |

Assists with maintaining a good working relationship with the board by ensuring there are no surprises and all relevant issues are brought to the attention of the board as early as possible. |

|

Sub Committees |

Appoints members of the board to necessary board sub committees. Ensures sufficient and appropriate delegation of responsibility. |

Attend and contribute to those sub committees of which they are members. |

||

|

Evaluation |

Perform the annual appraisal of the chairperson. Feedback on the results of the evaluation performed of board members. |

Leads the evaluation process of the full board and assesses individual members. Performs the assessment of the chief executive. Provides results of evaluations to the sponsor department if requested. |

Contribute to conversations and processes for evaluating the entire board. Actively engage in their own assessment. |

Chapter Four: Operating a Board

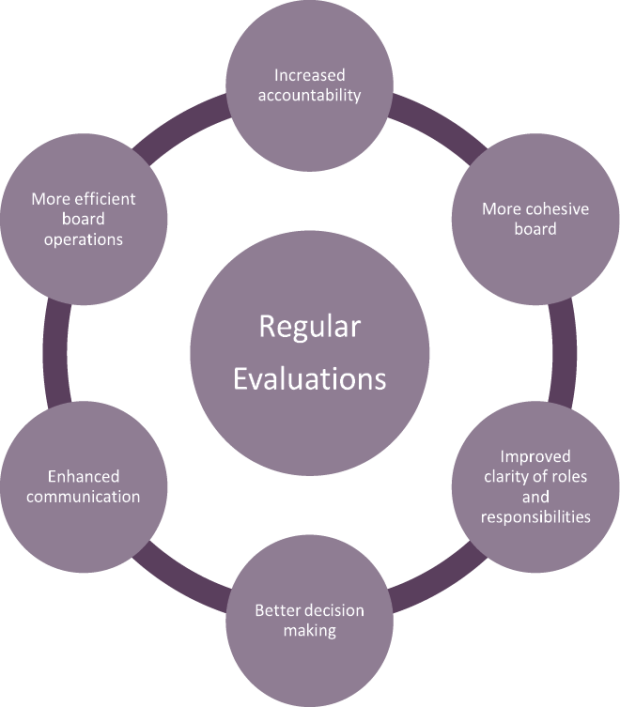

4.1 The successful operation of a board ultimately hinges on how the board conducts its affairs, particularly in the context of the board meeting. Key criteria for effective board operation are:

Frequency of Meetings

4.2 The board should, in the main, meet monthly on pre-determined dates and conduct special meetings normally at the request of the chairperson. This frequency allows the board to discharge its duties and maintain a working knowledge of the organisation’s current risks, issues and business activities. The effect of board meetings will be diluted if there are too many; although at times of rapid change, an increase in the number of meetings may be required. Annex 3 provides a suggested Board Annual Programme.

Length of Meetings

4.3 It is important to allocate sufficient time for each meeting to allow focussed discussion of agenda items. The length of the meeting should be set in advance and adhered to. This means starting the meeting on time and ending it on time. Normally a board meeting should last around two hours but definitely not more than three. Allocating time to agenda items according to their importance may help with this. Longer meetings can be symptomatic of inefficient discussion: going off on a tangent; the chairperson not managing time adequately; or having an agenda which is too long and unrealistic.

4.4 The time at which the meeting is scheduled is also important. Scheduling regular meetings for inconvenient times can have a negative impact on the morale of the board or its attendance levels. Emergencies are a reality of most organisations and may necessitate meetings at odd times, but routine meetings should be scheduled at a time reasonably convenient for all participants.

Agenda

4.5 It is the chairperson’s role to decide on the final content of the agenda. The agenda should:

- fit with the objectives of the board meetings;

- not be too long;

- have specific items for deliberation including sensitive items rather than just a list of general areas, for example standing items; and

- include cross references to the relevant items in the board papers.

4.6 The agenda also needs to be explicit about what items are for discussion, for decision or for information. This can be easily achieved by providing a key against each agenda item or annotating the top of the relevant board paper.

4.7 Consideration ought to be given to the order in which agenda items are listed and dealt with by the board. More routine items which do not require much consideration should be dealt with and cleared quickly, with strategic issues which necessitate decisions, making-up the substance of the meeting.

4.8 As stipulated before, it is a good idea to allocate a specific amount of time to each issue on the agenda based on its importance. It is ultimately the responsibility of the chairperson to manage time and keep discussions on track, although all participants have a duty to keep the meeting on track and stay on topic.

4.9 Whilst it is important to have clear agendas and to manage time well, a good chairperson does not put process ahead of substance and allows discussions to flow sensibly. Meetings should be disciplined, giving people the capacity to speak but not endless time to talk. A specimen agenda has been included at Annex 4.

Board Papers

4.10 A board pack is the main briefing tool for board members and therefore impacts on the board’s effectiveness in terms of its ability to debate and make decisions. It is the board’s collective responsibility to ensure its papers are sufficiently detailed and robust to enable members to fulfil their role and responsibilities. Where the volume or quality of information is not acceptable it is incumbent on the members to draw this to the attention of the organisation’s senior management. In addition, the board secretariat can act as a critical ally in quality assuring board papers.

4.11 Board papers should be fit for purpose, easy to understand and not take long to read and analyse. This means key information is not obscured by the provision of superfluous detail. Papers prepared for the senior management team are therefore not always appropriate for presentation to the board, as in many cases they contain detailed operational information. The papers supplied for each board meeting should be concise and strategic in nature. To achieve this, they should be distilled to remove extraneous information and draw attention to key strategic issues. Any financial information provided needs to be set in the context of non-financial data, to facilitate its comprehension.

4.12 Boards should consider applying a page limit to board papers on the agenda. It is suggested, based upon representation from board members, that the limit be set at no more than four pages in length. Where deemed necessary, the paper could provide a link to a fuller report on the issue or alternatively the board could request attendance at the meeting by the official with responsibility for the matter under deliberation, to provide further detail and answer any questions.

4.13 Generally board packs should not culminate in unrealistic preparation time and lengthy meetings. The board pack should help the board members, not burden them.

4.14 Board members must review the agenda and papers and arrive at the meeting prepared. Board packs need to be issued in enough time to allow for thorough preparation and consideration prior to the meeting. Best practice indicates this should be at least a week in advance or earlier if possible. If adequate information has not been provided on a timely basis then members should take the initiative and ask why. It is for the board to decide what information it needs and for management to meet those needs. The board, as part of the evaluation of its effectiveness, should review the format and content of its papers, as the focus and direction of the organisation may have changed with time. See below some suggestions for improving the format and content of board papers. MPMNI requires an evaluation of effectiveness, which is recorded each year in the governance statement, contained within the annual report and accounts. A specimen board paper has been included at Annex 5.

Figure 8: Aide Memoire for Board Papers

- Structure - each paper follows the same basic structure and is logical and intuitive;

- Scale - each paper is concise, so that the key messages are easy to identify;

- Scope - each paper focuses on the bigger picture; and

- Systems - consider using a board portal to distribute papers.

Use of Technology

4.15 Insufficient use of technology has been highlighted by board members in NI as one of the key weaknesses in the operational effectiveness of boards. The current working environment dictates a need for both security and efficiency in how information is communicated to members. There are many applications available which allow boards papers to be issued and viewed through a web-based facility.

4.16 Using such an application allows for:

- easy access to historical reports;

- board information to be updated or refreshed as needed;

- timeliness of distribution; and

- reduction in the cost of distribution in comparison to posting.

This ensures no more bulky board packs, late deliveries or lost and stolen documents.

Minutes

4.17 Minutes produced should capture the essence of the meeting held. Keep the minutes brief but they should still capture the contribution of individual members and be reflective of the actual discussions, decisions made, actions agreed and responsibilities allocated.

4.18 Minutes should not be biased towards management interpretation. To ensure they are a complete and accurate recording of the meeting, minutes should be distributed promptly to members for consideration and comment no more than two weeks after the meeting. The minutes should then be agreed, with amendments, at the subsequent board meeting and action points appended for tracking purposes. Minutes are key documents of accountability. These should be retained for reference. See Annex 6 for board minutes template.

Conflicts of Interest

4.19 It is important the independence of each board member is managed and maintained. A register of interests should therefore be held, kept up to date and publically available.

4.20 Specific conflicts should be known prior to the board meeting and papers being issued. The secretariat and chairperson should be aware of any declared interests so they can be managed in advance of each meeting, for example, members with conflicts are not given sight of the board papers in relation to the matter with which they have an interest and are able to excuse themselves from the actual discussion during the meeting.

For more information on managing conflicts of interest see:

Conflicts of Interest : A Good Practice Guide, NIAO, March 2015.

Decision Making

4.21 Decision making is a key duty of the board and all members have a collective responsibility for taking informed and transparent decisions within its scheme of delegation.

4.22 There needs to be a continuous focus on the outcomes the board wish to achieve within the setting of the meeting. A board should not be hindered in its decision making by:

- a dominant personality;

- failure to consider risk properly;

- failure to allow adequate time for discussion; or

- a lack of high quality information or expert opinions when necessary.

4.23 How should the board approach decision making in the most effective way?

- Maintain a critical approach to all decisions.

- The chairperson, who is an experienced facilitator, should maintain a neutral position until all viewpoints are heard.

- Judge all available options, perhaps through a pro/con list.

- Thoroughly consider the implications of all decisions, stepping outside the boardroom if necessary to understand what happens in reality.

- Question the validity of the information presented, and on which decisions are based.

- Ensure decisions are documented sufficiently.

Conflict Resolution

4.24 Constructive tension, if managed well, can bring about change and allow the board to evolve over time. However, tensions are often not dealt with adequately or at all. This can have a negative impact on relationships and board performance and morale. Frequently this leads to members choosing to resign their position rather than attempting to rectify the situation. Consequently the board can become one dimensional, with the issue or conflict having a disabling effect on the board’s operation.

4.25 A board should have mechanisms in place to deal with disputes and conflicts to ensure they do not become wider issues and impact on the effectiveness of the board. Detailed below are some ways in which conflict can be prevented or addressed when it arises.

Figure 9: Suggested actions to combat tension

- Induction should include an opportunity to build relationships between the board members on a personal level, to aid in the formation of trust and respect.

- Further time, perhaps once per year, should be set aside to reflect on and discuss communication within the board.

- Limit potential for conflict through clearly documenting roles and responsibilities.

- Ensure all members receive the same information and there are no ‘offline’ discussions which do not include all members.

- Provide training for all members on negotiation and conflict resolution as part of the annual training plan.

- Put in place a written code of conduct to guide members’ behaviours.

- The chairperson should ensure resolutions are obtained and, if required, involve a neutral facilitator should the situation warrant it.

Rather than discussing the issue of contention during a board meeting, a separate meeting should be held outside of the board to air issues and come to common ground.

Risk Management

4.26 Robust risk management goes hand in hand with the board’s ability to make decisions. Decision making is most effective when ownership and accountability of risk is clear. Clarity on the role and functions of the board and that of the Audit and Risk Assurance Committee are therefore essential.

4.27 Sufficient time and resources should be allocated to risk management, as the board has ultimate accountability for, and ownership of, the organisation's risks. Scrutinising and advising on key risks is a matter for the board. The board should, however, be supported by the Audit and Risk Assurance Committee.

Figure 10: Responsibilities of the board for risk management

- Establishes and oversees risk management procedures;

- Endorses the risk management strategy/policies;

- Ensures appropriate monitoring and management of significant risks by management;

- Challenges the risk management adopted by the organisation to ensure all key risks have been identified; and

- Is aware of any instances where risks are realised.

4.28 The board must understand and agree the organisation’s risk appetite and be familiar with current best practice in risk management for identifying, assessing and managing risk. Once processes have been established and are embedded, the board should continue to challenge management on compliance and the operational effectiveness of the risk management processes.

4.29 This is not a one-off activity. Risk management should be a standing item on the agenda of the board, whereby the board regularly deliberates on the current risks captured and maintained on the risk register; the risk appetite assessed as tolerable for the organisation; and ultimately engages in horizon scanning to identify risks at the margins of current thinking and planning.

For more information on risk management see:

Good Practice in Risk Management, NIAO, June 2011.

Chapter Five: Evaluating a Board

5.1 Boards require feedback on how they are performing as a group and how individual members are fulfilling their responsibilities. The purpose of any assessment is to evaluate effectiveness and make improvements where required. There is no definitive way of carrying out an assessment but it is important to modify the process over time to retain interest and relevance. Establishing an effective process for board evaluation can send a positive signal to the organisation that board members are committed to doing their best. It also sets the necessary example for the establishment of robust appraisal systems throughout the organisation.

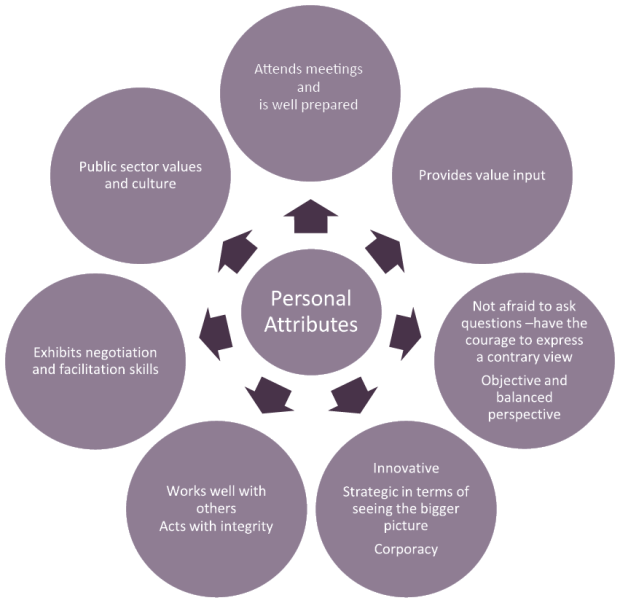

5.2 Evaluation of performance is central to corporate governance. Experience shows that a successful board is not guaranteed by just bringing together successful people. All boards can benefit from evaluation.

5.3 Figure 11 summarises some of the potential benefits of regular evaluations.

Figure 11: Benefits of Evaluation

Board Evaluations

5.4 A board should undertake an evaluation of its own effectiveness annually. Some boards do this as part of an annual awayday. This process can be seen by some as a chore and a tick box exercise; however an effectiveness evaluation is a powerful mechanism.

5.5 The chairperson sets the tone from the top and plays a pivotal role in the evaluation. It is therefore vital that the chairperson reinforces the significance and value of the evaluation process and encourages board members to participate fully.

5.6 The actual form of assessment should be tailored to each board; there is no universal template. Figure 12 outlines some of the topics board evaluations should cover.

Figure 12: Topics for consideration during Board Evaluations

- whether the board has adequately discharged its responsibilities, for example strategic planning, budgeting, risk management etc.

- the adequacy of board operations and decision making processes, for example adequacy of information, committee structure, board composition, discussion time etc.

- other areas such as board culture*, working relationships, opportunities for meaningful participation, communications with management and other stakeholders.

*[Note one of the key issues raised by board members is not feeling empowered to speak up during board meetings. A board evaluation is a good place to check if members feel they can do that.]

5.7 Consideration should also be given to external facilitation of board evaluations. A good external facilitator can add a different perspective and be both challenging and reassuring. They can provide independent and impartial advice, objectivity and rigour, leading boards to make changes that positively impact performance.

5.8 Engaging an external reviewer incurs cost but this should be weighed against the benefit that independent evaluations can provide.

5.9 Benchmarking can also help the board identify potential areas for improvement. It can be used to gauge performance against a baseline, best practices and other boards. Organisational benchmarking could be used to compare the board’s structure and performance with the accomplishments of others. If for example, another board has achieved successes through governance transformation, the board could do a compare and contrast analysis of their leadership and decision making processes with a view to identifying areas for improvement.

5.10 Board effectiveness evaluations can be simplified using a self-assessment instrument, such as a checklist. There are many different checklists available but they can have limitations. To be of value, more than a Yes/No answer is required. Good checklists describe best practice in areas such as strategic thinking and planning; board responsibilities; board appointment and composition; board operation; board relationships and ask respondents to rate their board in the different areas. This allows open-ended comments on how the board’s performance could be improved in each area. If designing a checklist, the questions included should:

- be thought provoking;

- be designed to gather information not readily available e.g. not asking the board members for their attendance, when this is available from the board secretary;

- not be repeated each year, so as to avoid routine answers;

- contain open questions to glean insight and ideas from board members; and

- cover the real drivers of board effectiveness e.g. how are relationships working in practice.

5.11 To achieve a holistic assessment, you should also consider gaining the perspectives of more than just current board members. Ascertaining the views of the executives should provide further insight as to how the board is operating and contribute to the overall evaluation.

5.12 Once the evaluation has been completed, it is important that feedback is shared amongst the board members. In addition the board needs to address any areas for improvement and put an action plan in place. This may comprise feeding the results of the evaluation into future appointments, induction and training plans. The resulting strategy for improvement should provide a framework for future development and have a defined timescale for implementation.

5.13 Once again the role of the chairperson is key. On any subsequent agendas the chairperson must ensure any actions or follow-up points from the evaluation are introduced so they are acknowledged and implemented.

5.14 Evaluation is about learning and improving. The evaluation feedback should allow the board to build on the positive aspects and gain a greater understanding of how they operate and compare with best practice. Attention should always be drawn to achievements and in-year successes.

Individual Evaluations

5.15 Annual board member evaluations should also be undertaken. It is the responsibility of the chairperson to ensure these take place. Such assessments can adopt a two-staged approach.

5.16 The first stage is conducted by the individual member through the use of a self-evaluation form. This is normally for personal use, in that it is not to be handed in or reviewed by anyone but the individual. It does however help to inform the second stage, which is the assessment interview or discussion between the board member and the chairperson.

Self-Evaluation

5.17 Figure 13 below highlights some of the factors a board member should consider as part of self-evaluation.

Figure 13: Questions to consider for self-evaluation by the board member

- I am familiar with the organisation’s mission statement, vision and corporate plan.

- I am familiar with the laws and regulations which govern the organisation.

- I am familiar with the governance framework of the organisation.

- I help to further the mission and goals of the organisation with my time commitment, skills and support.

- I regularly attend board meetings and other events requiring board participation.

- I am available to serve on committees as needed.

- I come to meetings having already read the information relevant to that meeting and prepared with questions.

- I try to be an objective decision-maker.

- I avoid participation in board issues which are self-serving or may be perceived as conflicts of interest.

- I understand and am comfortable with the board’s decision making process.

- I offer constructive challenge to board discussions but publicly support board decisions.

- I treat other board members with respect and listen openly to their opinions.

- I understand the role of the board and my responsibilities as a board member.

- I understand the difference between the executives’ responsibilities and my own as a member of the board.

- I encourage and support the organisation’s executives in achieving organisational goals.

- I visit the organisation frequently enough to be familiar with its services/ activities and to identify potential issues or needs.

- I keep abreast of legislation and other developments in the sector that might impact on the organisation.

- I have a good working relationship with the chairperson, other board members and executive team.

- I have established working relationships with relevant stakeholders and discuss pertinent issues with them advocating for their support and direction.

- I find serving on the board to be a satisfying and rewarding experience.

If each question represents 5 points, the total points available are 100. A score of 75 or more is desirable for a good board member.

Assessment Interview

5.18 The assessment interview should be conducted with reference to the clear expectations normally required of a board member. These are set out in various key documents such as the organisation’s MSFM, the terms of reference for the board and the code of conduct for board members. Such documents should have been made available to the individual board member on appointment and covered in any induction training. The various topics that should be covered in the assessment interview are outlined below at Figure 14.

Figure 14: Topics to be covered in the Assessment Interview

- the level of the member’s skills, experience and demonstrated expertise;

- the level of the member’s preparation for board discussions and the degree of participation in them;

- the member’s knowledge of the organisation, its strategic direction and its operational environment;

- the member’s record of attendance;

- the member’s ability to express views and hear the views of others;

- the member’s ethical standards; and

- the member’s commitment to the best interests of the organisation, such as its core values and behaviours.

5.19 Should there be any issues of concern arising with the performance of a specific board member, more frequent evaluation may be justified.

5.20 Many chairpersons find addressing under performance difficult to manage. This occurs through non-attendance, insufficient effective contribution and disruptive conduct. There has historically been a preference to allow people to serve out their term rather than taking more specific action. However, chairpersons need to act resolutely. When an ethical issue arises with a board member, it must be dealt with promptly and decisively, as any delay could have far-reaching consequences. Some ways to approach performance concerns are outlined in Figure 15.

Figure 15: Ways to address performance issues with a board member

If a board member has consistently not attended board meetings or makes minimal contribution to the effectiveness of the board and is actually obstructing the work of the board when they do attend, the evaluation process can be an opportune way of tackling the problem sensibly and professionally. It gives the chairperson a chance to have an open, honest dialogue. This should focus on the organisation and not the person. There is a need to change the behaviour not the person, because doing so will better serve the organisation. Avoid vague generalities. Be specific, describe behaviours. This can help illicit a fruitful conversation rather than a defensive argument.

A suggestion for poor performance made by other board members, who attended the NIAO focus group sessions, had included the implementation of a policy of ‘three strikes and you’re out’. After missing three meetings the individual is asked to account for their attendance. This obviously would warrant a discussion with the individual member at the time, rather than waiting for an annual evaluation. However, should overall attendance for an individual be less than 75 per cent for the year, this should be discussed at the annual evaluation. The removal of a board member is, however, a decision for the minister.

It is important to keep in mind that there are many ways to solve issues with board members, but finding the solution starts with finding the root cause and understanding that there are a number of reasons why a board member might not act as expected. The evaluation process can be a key mechanism for finding that solution.

Peer Evaluation

5.21 A third component that could also be included in the evaluation process is peer review, commonly used in the private sector and to a lesser extent in the voluntary sector. It is frequently argued that peer evaluators can be biased or unwilling to make hard judgements. Some board members find the prospect of peer review unsettling as they see it as potentially setting members against one another. Peer review can however be a useful source of information and a tool to improve board member performance. It gives every member of the board a voice and makes them more accountable to each other and to their role/responsibilities. For peer review to be successful it needs to have buy in from all members in that they are accepting of the judgement and advice arising from the evaluation. There is comfort in knowing your peers are not only judges but rather an important part of the whole evaluation process. A typical board member peer evaluation form can be found at Annex 7.

5.22 The depth and complexity of the evaluation process should be agreed by each board in order to meet its own needs. It is important that the assessment used by the board is robust and meaningful. As a minimum, individual evaluations should require an annual discussion of performance with the chairperson whereby any training or development requirements can be identified and the opportunity is afforded to individual members to raise any issues on the overall performance and operational effectiveness of the board.

5.23 As with board level evaluations, individual evaluations do not end with the outcome of the evaluation. It is equally important that there is appropriate follow-up. Once the assessment is completed, the chairperson should make certain that steps are taken where necessary to improve the effectiveness of the individual board members. For example, the outcomes could feed into individual training plans and consideration over re-appointments.

5.24 Individual evaluations should be viewed positively; as a constructive means by which to benefit both the performance of the individual and the board. The Public Appointments Code NI requires that evidence of effective performance is necessary when reappointment of a public appointee is being considered.

5.25 Outside annual evaluations, boards should also devise other mechanisms to ensure on-going performance improvement. Figure 16 below provides some suggestions.

Figure 16: Performance Improvement Mechanisms

- chairperson seeking feedback from members after each meeting;

- appointing a member responsible for ensuring ongoing improvement and creativity in the way the board operates;

- ensure members are aware of the method for raising concerns or suggestions; and