Abbreviations

MOU: Memorandum of Understanding

NIAO: Northern Ireland Audit Office

OBA: Outcomes Based Accountability

PFG: Programme for Government

SLA: Service Level Agreement

SRO: Senior Responsible Owner

Part One: Introduction

1.1 In June 2018 the Executive Office launched an outcomes delivery plan setting out the actions that departments intend to take during 2018-19 to give effect to the previous Executive’s stated objective of “Improving wellbeing for all – by tackling disadvantage and driving economic growth”. The plan’s starting point is the framework of 12 outcomes that was developed by the previous Executive, consulted on and refined during 2016-17 (Appendix 1).

1.2 The plan reflects the responsibilities placed on departments by the previous Assembly and Executive to work collaboratively, reflecting the reality of how people see public services with a focus on impact and outcomes, not on the administrative structures for delivery. Working in a collaborative way across departmental boundaries to achieve impact is a significant challenge. There is also a local government dimension, with each of the 11 councils now delivering, through partnership working, community plans that respond to the needs of their areas. Central and local government working collaboratively with the voluntary and community sector also adds value to public services, bringing specialist or local knowledge or experience and links with communities.

1.3 This Guide provides practical advice and guidance to encourage open and constructive collaborative working between public sector organisations and with local communities. The Guide is intended to complement current guidance and brings together best practice in partnership working drawn from local, national and international work relevant to the public sector in Northern Ireland. It includes a self-assessment checklist for public bodies that will assist in developing effective collaboration (Appendix 2).

1.4 This is the second of a series of good practice guides designed to support the delivery of the new outcome-based approach in the Programme for Government (PfG). It follows the publication of the good practice guide “Performance management for outcomes” in June 2018. Two further guides, on innovation and engagement, will be published in the coming months.

Partnerships are key to delivering PfG outcomes

1.5 Effective partnership working across all of government will be key to the planning and delivery of improved outcomes. Figure 1 summarises the Executive Office overview of its outcomes-based approach to the PfG and shows the connections between outcomes, indicators, actions and performance measures.

Figure 1: The outcomes-based approach to the Programme for Government (PfG)

Source: The Executive Office

“These outcomes will be delivered through collaborative working across the Executive and beyond government and through the provision of high quality public services” (Outcomes delivery plan 2018-19: The Executive Office, June 2018)

1.6 The PfG established a framework of indicators that will present evidence of impact against each of the 12 PfG outcomes. Effective partnerships and collaboration between government departments, local government, other agencies, the private sector and the public are at the heart of performance accountability and key to the delivery of effective outcome-based programmes and projects.

Structure of guide

1.7 This Guide follows the main stages in the lifecycle of a partnership, identifying potential barriers to success and levers to overcome them. It covers:

- Part 2: Scoping, identifying and building a partnership;

- Part 3: Planning, managing and resourcing a partnership; and

- Part 4: Implementing, measuring and reviewing a partnership.

Part 2: Scoping, identifying and building a partnership

Effective partnerships need to work across all of government

2.1 Partnership activities in government are not new. Public officials from different organisations work across departmental boundaries to deliver government services; collaborate in the development of policy; and exchange information and professional expertise. Regardless of the size or nature of the collaboration, operating across traditional departmental boundaries can pose challenges, however they often provide innovative solutions to difficult issues, enabling local communities to interact with public services. sets out an example of how Policing and Community Safety Partnerships (PCSPs) have helped develop Support Hubs, also known as Concern Hubs, which formalise collaborative working amongst statutory agencies at a local level, sharing information to allow them to work with vulnerable individuals to improve their circumstances. This is a good example of how a collaborative approach can produce successful outcomes which cannot necessarily be achieved through one public service body.

Partnership arrangements come in many forms

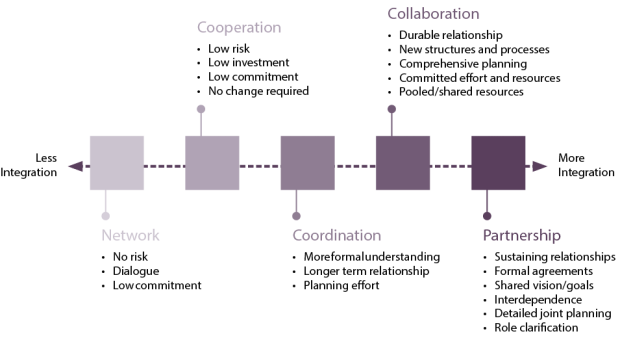

There are many levels of partnering and relationships must be responsive to changing requirements and circumstances:

- Collaborations may begin with simple exchanges of information, but may develop into more formal and extensive relationships

- Partnership arrangements must be adapted to the needs and characteristics of the project or programme and the partners involved

- In reality, partnerships are combinations of networking, cooperation and collaboration, working to achieve coordination

- Arrangements that require more integration will have greater resource needs

- What drives the complexity of the arrangements are the nature of the issues being addressed and the level of collaboration required between partners

All collaborative arrangements require discipline, clarity and a well organised approach to working arrangements

Collaboration is necessary to achieve PfG outcomes

PfG Outcome 4 (“We enjoy long, healthy, active lives“)

“for individuals, families and communities to take greater control over their lives and be enabled and supported to lead healthy lives, active collaboration is needed across government and with local government, the community and voluntary sector, private businesses and other organisations and delivery partners to address the factors which impact on health and wellbeing.”

Identify the appropriate level of collaboration in advance

Source: Adapted from model Developed by Success Works, 2002 and included in Putting Partnerships into Practice Final Report. Report prepared for the Department of Human Services 2004 (Australia).

Why have a partnership?

2.2 The launch of the PfG has increased awareness of the importance of focusing on the user’s experience of public services. This often means that public bodies must work together both to deliver services that are tailored to user needs and to plan and deliver co-ordinated service strategies. Although the principles underlying this kind of collaboration are simple, it is often difficult to achieve in practice.

2.3 Real partnerships do work and are worth the time and effort to establish. Partnerships are about sharing creative practices and sharing risk and responsibility. Effective partnerships also enable tasks to be more streamlined and, if established properly, the productivity of a partnership is higher than each partner working separately. Activities are often driven by the need to deliver statutory obligations and good partnerships across a range of sectors can help deliver more effective public services. However, partnerships can often be faced with budgetary pressures; tight deadlines; and complex guidelines. This can lead to partners feeling pressure to protect their individual organisation and not commit fully to the partnership. Many management structure models are available, but agreeing a model and working to it is key.

Initiating partnerships

2.4 The PfG Senior Responsible Owners (SROs) have a key role in bringing together the various actions from different departments and public bodies that contribute to the population accountability outcome for which they are responsible. This approach should be proportionate, recognising that some bodies will have a very focused or specific contribution to the PfG outcome framework. However, the SRO can help the process, by providing resources for identifying and brokering partnerships.

Initiating partnerships

There are two important roles in establishing a partnership:

- The initiator: the individual responsible for identifying the original concept or creating the vision; and

- The broker: the individual identified as the person who sets up the partnership. The brokering role builds relationships between stakeholders, facilitates negotiations, mediates conflict or dispute, records and documents information and drives the development process forward. This will include helping public bodies to identify the most appropriate PfG outcome with which to align; the establishment of appropriate partnership arrangements; and the performance measures and indicators against which progress will be assessed.

Sometimes the initiator can also be the broker. However, the brokering role can also be fulfilled by another stakeholder with the skills and motivation to drive the concept forward. Whatever the decision, roles should be assigned for this initiation phase of the partnership and be open to review in the next phase of development for the partnership.

2.5 It is important that preliminary discussions are held with potential partners (including funding body or bodies) to discuss relevant issues prior to making a decision that a partnership is desirable. Each organisation must be ready, willing and able to partner. Time spent up front in establishing a firm foundation will pay off in the long run, greatly increasing the probability of the partnership’s success.

2.6 The initial meeting of a partnership is key as it establishes the appropriate level of collaboration. The reasons for establishing the partnership must be clearly articulated, understood and accepted by all members. The initial meeting is also crucial to building effective relationships and collaboration. Appendix 3 sets out a suggested agenda for this initial collaboration/partnering meeting, to help keep the collaboration on track and ensure that each partner agrees the specifics of the collaboration. Importantly, the initial meeting is about establishing an understanding of each other’s organisational culture and operating environment.

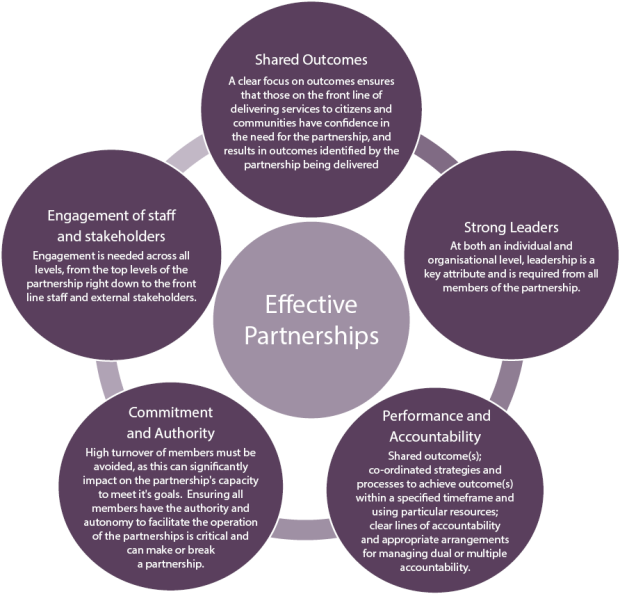

2.7 A key challenge for any partnership is understanding the environment in which it will operate. Part 3 of our good practice guide “Performance management for outcomes” (paragraph 1.4) provides guidance for public bodies on building lasting stakeholder relationships that will help officials and partners at all levels develop an understanding of the public’s needs and expectations. Figure 2 sets out the features of an effective partnership.

Figure 2: Features of an effective partnership

Work together towards a shared outcome

2.8 Working relationships are more important than any model or structure of delivery and the ability of public sector partners to work together to achieve outcomes for citizens and communities is the key to effective partnership arrangements. Forming new partnerships or bringing new members to an existing partnership takes time and will require several meetings for the dynamics of individual partnerships to ‘bed in’. It is, however, an important part of the life cycle of the group.

Outcome-Based Accountability: key steps:

- Identify what outcomes you want to achieve (high-end targets).

- Choose what indicators best measure these outcomes.

- Identify how to change these measurements, making progress towards the desired outcomes – “Turning the Curve”.

- Decide what works / is working, using data analysis.

- Ensure a flexible and dynamic approach, evolving and adapting in accordance with the evidence.

Strong leaders are essential

2.9 Identifying the most appropriate structure or model of collaboration or partnership for delivery of outcomes requires strong leadership. At both an individual and organisational level leadership is a key attribute, required from all members of the partnership – from the chair; from partners on behalf of their organisations or the group they represent; and from partners who are required to lead on specific issues. To promote a sense of ownership, staff at the operational level also need to lead. However, the chair of any partnership needs to possess the skills, personality and capacity to provide strong leadership, while maintaining inclusive processes and practices to maximise the engagement of all the partners.

Embedding performance and accountability

2.10 To enable members of a partnership to perform well individually and collectively, each partner’s expectations, responsibilities and functions need to be clearly identified, documented and understood, including the arrangements for funding; monitoring of progress; and performance reporting.

2.11 The fact that any one partner is responsible for all the actions needed to achieve successful outcomes can be a difficult issue. A lead organisation with authority to drive the agenda provides clarity, but it may also be appropriate to establish a joint approach in which all bodies share accountability at the aggregate level, as well as having individual accountabilities for facets of the partnership. Whatever path is chosen, identifying potential risks (either to one body or shared risk to the partnership) is better conducted early in the partnership planning process and reviewed regularly.

Membership commitment and authority

2.12 Consistency of membership, from an organisational and individual level, is important to maintain the connection and momentum within the partnership. Commitment to the partnership is an important behaviour, and a high turnover of members must be avoided as this can impact significantly on the partnership’s capacity to meet its goals. Ensuring all members have the authorisation and autonomy to commit their own organisations to action is critical and can make or break a partnership.

2.13 Transparency in financial management at all levels is important for cross-entity activities. Appropriate systems should be established early, so that expenditure against milestones and deliverables can be monitored properly. This supports comprehensive management reporting and the ongoing management of partnership issues. It is also important to consider how much time a person can lend to the partnership and any financial and non-financial resources that are available to commit to the administrative support function (for example, agendas, minutes and overall coordination, joint actions, initiatives, planning and evaluation).

Engaging staff and stakeholders on the front line

2.14 Staff and stakeholders should be engaged at all levels, from the top levels of the partnership down to the front line. Strong engagement helps to maintain the common purpose of the partnership and to increase its effectiveness. Communicating the objectives and desired outcomes of the partnership clearly, before or just after the launch of the partnership, may offer senior members the opportunity to review arrangements or to address more effectively the issues on the ground.

Forming partnerships outside government

2.15 The outcome-based approach places an additional requirement on public bodies to take a broader view to delivering outcomes for citizens and communities. Wider engagement and participation with the voluntary and community sector and the private sector are necessary elements of this approach. Indeed, the involvement of an appropriate mix of government, private sector and not-for-profit contributions has at its heart the objective of achieving value for money and improved delivery of public services.

2.16 Retaining the openness, transparency and accountability that is expected in the public sector can be a key challenge. Private sector or community institutions that are willing to deliver outcomes on behalf of government may be used to operating under governance structures different to those of the public sector. However, any public body that engages with external partners must remain accountable for expenditure of public money and for achieving outcomes. The commissioning body (or partnership) therefore needs to negotiate operating arrangements that meets public sector transparency and reporting requirements, but still allows the partner to engage and deliver effectively.

2.17 In 2010 we published a report Creating Effective Partnerships between Government and the Voluntary and Community Sector. With support from the Northern Ireland Council for Voluntary Action, we identified examples of good practice and examples where, through better co-ordination and a joined-up approach, public bodies could make a significant difference by reducing bureaucracy and administration costs and improving value for money for both themselves and the sector.

Part 3: Planning, managing and resourcing a partnership

Leadership, governance and performance management

3.1 A 2015 review by What Works Scotlandpresented evidence from empirical research on UK public service partnerships. The paper included a review of the key assumptions and risks underpinning effective partnership working, highlighting the need for effective leadership, governance and performance management in developing and maintaining partnerships (Figure 3).It identified that centrally imposed performance management requirements can act as a major barrier to effective partnership. It highlighted a key challenge for partnerships: to develop robust and meaningful systems of leadership, governance and performance management to allow a partnership to work responsively and flexibly.

Figure 3: Conditions for effective partnership working: assumptions and risks

|

Assumptions |

Risks |

|---|---|

|

This is a partnership |

Term ‘partnership’ used cynically to mask hierarchical arrangements |

|

Partnership is the appropriate form of organisation to address this issue |

Partnership formed naively as it seems the right thing to do |

|

There is a clear need and rationale for the partnership |

No clear sense of purpose and outcomes |

|

There are shared understandings of final outcomes |

Programme of work complex and unwieldy |

|

The partnership has sufficient autonomy and authority to make decisions |

Not all partners involved in decision making and agreeing direction of partnership |

|

All partners are involved in clarifying direction and decision making |

Voluntary and community sector excluded and marginalised |

|

There is effective power sharing across the partnership |

Operational staff excluded from strategic decision making |

|

There are sufficient resources to deliver on objectives |

Work of the partnership dominated by performance management reporting requirements |

|

Timeframes are realistic |

Lack of ownership amongst partners |

Source: What Works Scotland Evidence Review: Partnership working across UK public services: December 2015

Establishing clear roles, responsibilities and governance arrangements

3.2 Partnering arrangements involve public bodies working together towards a shared objective. As partners, the bodies are collectively responsible for the operation of any partnership agreements and the achievement of outcomes. This accountability can have three dimensions:

- horizontal accountability obligations among the partners;

- vertical accountability between a public body and the source of its resources and its contribution to the partnership; and

- collective accountability of all partners to a PfG SRO included in the PfG delivery plan (paragraph 1.4) for the success of the partnership.

Map the partnership for clarity

Gaining an understanding of the breadth and span of its influence and the extent of its rep-resentation can be a key challenge for any new partnership. Mapping a new partnership will:

- identify organisations and other key stakeholders and any strategic alliances that need to be involved;

- identify current service systems or pathways through the partnership using the end user (client) perspective;

- analyse the key relationships and how they currently operate; and

- assess the current and potential value of each opportunity and relationship.

Proper definition and communication of each partner’s role(s) and responsibilities is important

|

It allows each partner to: |

Nevertheless, it is also important to: |

|---|---|

|

|

|

Early attention should be given to embedding the governance arrangements into the collaboratiacve process. Major policy initiatives or programmes will generally benefit from the appointment of a lead department and/or a management committee with a nominated chair and representatives from the lead department and other partners. |

Effective governance arrangements create a firm basis for decision-making and performance monitoring and can help to prevent unnecessary duplication of effort and administrative risk. |

Communication is vital to success

3.3 Effective communication arrangements should be established at the beginning of the partnership. Identifying the target audiences, developing clear messages and communicating them effectively will increase the likelihood of initiatives and their outcomes being accepted and successful. Good communication not only keeps people informed about what is going on, it promotes trust and a friendlier and satisfying working relationship; creates a more productive environment; helps to avoid conflict and helps partners achieve their objectives.

Effective communications

- Establish a communication plan and process - good communication among partners does not happen unless there is a plan in place and a process has been identified to support the communication.

- Identify who is responsible for communication between the partners.

- Identify what information needs to be shared and with whom.

Build good governance through written agreements

3.4 Written agreements between partners can provide a foundation for sharing a range of government services and expertise, from data sharing between two entities to the implementation of complex social reforms through multiple departments. Signing a partnership agreement is an indication of a public body’s intent to carry out the functions and obligations in the agreement. There are hundreds of such agreements in place across the public sector. However, the appropriateness of such agreements and the benefits they deliver can be variable.

3.5 A Memorandum of Understanding (MoU) is the most common type of partnership agreement. It records the common intent and agreement between two or more parties and defines the working relationships and guidelines between collaborating groups or parties. Further guidance on building an MOU is included at Appendix 4.

Part 4: Implementing, measuring and reviewing a partnership

Embedding performance management for outcomes

4.1 The PfG framework provides an overview of the key strategic priorities for the (former) Executive. To be effective, it must be underpinned by robust performance management arrangements in each of the public bodies that contribute to the delivery of the intended outcomes. “Performance management for outcomes” provides an overview of the outcomes-based approach, providing a framework for better planning and delivery of public services (paragraph 1.4).

4.2 The principles of performance management apply equally to partnership working. Managing performance in a partnership is complex. Partners are likely to have different decision-making and accountability arrangements, organisational cultures, planning and performance systems. This can be de-stabilising and act as a brake on partnership performance. It is important that partnerships establish strong performance management arrangements as early as possible, to ensure partners have a shared commitment, understanding of priorities and the ability to measure impact.

Sharing risks

4.3 The complexity of risk management is often compounded for partnerships. Taking a structured and broadened approach to risk management is therefore particularly important. This should include careful consideration and monitoring of risks (particularly any shared risks) facing each of the partners throughout the development, implementation and review stages of cross-cutting work as well as specific risks relating to the process of collaboration and partnership. It is important that these risks are considered in the context of the delivery of the overall outcome being sought.

4.4 The process can be helped by assigning a specific risk or group of risks to a single lead organisation, even if the risks span more than one of the partners. Clearly, this has to be linked with suitable mechanisms to monitor the risks, communicate any variations in the risk profile, and alert partners to challenges requiring corrective action. The use of ‘traffic light’ progress or status reports is one way that entities manage such situations effectively.

4.5 The NIAO has published good practice on Risk Management which is tailored to the experiences and needs of public sector bodies in Northern Ireland. It includes examples to illustrate how well risk is handled in practice and identifies better and more innovative ways of managing risk.

Anticipating and managing conflict

4.6 Successful partnerships recognise that conflict is a natural part of partnering with diverse groups, and are able to anticipate and use conflict constructively. Discussion and the documentation of a process for resolving differences and conflict situations is essential at an early stage.

Tips on managing conflicts

- Create a sense of interdependency among partnership members.

- Provide regular information to all partners to create a sense of being well informed.

- Work continuously to maintain a high degree of trust among partners.

- Create a process of decision-making that is perceived as fair and open by all partners.

Understanding partnership lifecycles

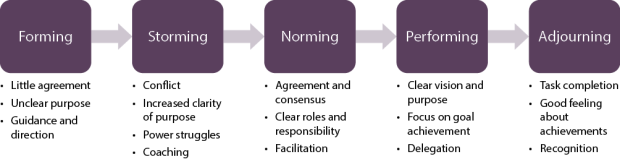

Partnerships go through different stages of development and growth at different times depending on where the partnership is in its life cycle. The stages at Figure 4 are adapted from Tuckman’s model. Understanding the challenges at key points will help the members identify appropriate strategies to sustain the partnership.

Figure 4: Partnership Lifecycles

Source: Group & Organization Management: Vol. 2, No. 4, 419–427; Tuckman, B & Jensen, 1977

Success depends on sustaining the partnership

4.8 The success of any partnership depends on sustainability, particularly in an environment where leadership, administrations, and policy makers may change. Maintaining energy and sustaining the partnership over a long period requires partners:

- to have a sense of interdependence;

- to be recognised and rewarded;

- to align planning with action; and

- to create a learning environment.

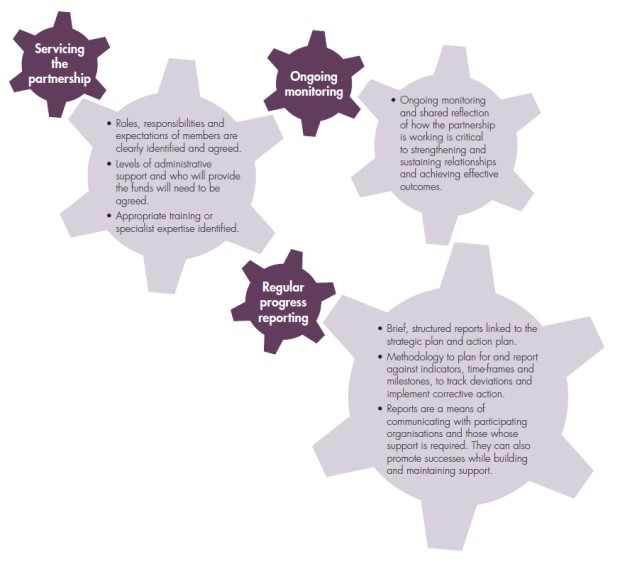

A competent, well-supported partnership is essential to success. Ongoing monitoring will ensure that relationships are sustained and regular progress reporting will help maintain support and enthusiasm.

An outcome based collaborative approach is a long-term commitment

4.9 Adopting an outcome based accountability approach (OBA) in the context of partnership working requires a cultural and organisational change process, demanding the necessary time and resources to implement. OBA performance accountability by service delivery organisations is regarded as being easier to implement than the population accountability indicators included in the PfG, as it focuses on services delivered. However, population accountability is a much more strategic and longer-term commitment. The development of performance measures by service delivery bodies requires them to move out of silos: beyond their own services and directorates, engaging in collaborative work with other organisations and agencies which have a role to play in improving well-being for all citizens. Recognising the importance and long term nature of this work is key to achieving better outcomes at a wider population level.

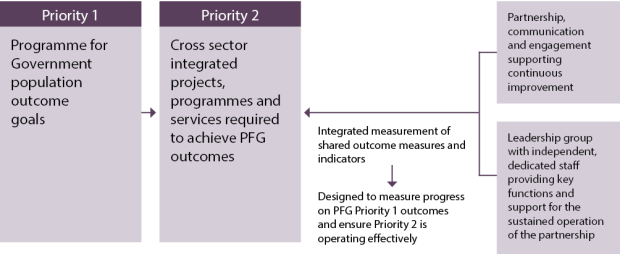

4.10 In the PfG environment, it is important that partnerships are based on a structure that fosters a shared leadership for desired outcomes and engagement with key stakeholders and the community. Figure 5 presents a potential structure for helping to ensure that those partnerships have a clear line of sight on PfG outcomes. It includes a leadership group with representatives from the key outcome owners, which provides direction and authority for the partnership and the necessary support and evaluation systems.

Figure 5: Suggested model for delivery of Programme for Government outcomes

Source: NIAO

Evaluating the partnership

4.11 Evaluating the partnership is at the heart of success. Performance information provides the facts for the partnership, to know if it is on track or if it needs to take action to correct and improve its performance or, perhaps, cease ineffective actions. Evaluation requires a range of actions that require planned, consistent and systematic collection of data about the activities, characteristics, and outcomes using a shared measurement system for monitoring performance.Effective progress monitoring and a commitment to action if things do not go well are essential to avoid the pitfalls of partnership working.

Common reasons why partnerships fail

- Rationale behind the establishment of the partnership was not clearly articulated, understood or accepted by stakeholders.

- Underestimating the time to establish a partnership – developing a trusting relationship of mutual benefit takes time and effort.

- Partners do not recognise their interdependence and the value of partnering.

- Lack of clarity of purpose or failing to recognise potential participation constraints.

- Lack of authority – partnership does not have authority to make decisions nor key responsibilities.

- Failure to lead – partnership suffers from lack of shared vision, purpose or direction.

- Inadequate resourcing of partnership activities.

Appendix 1 PfG outcomes framework (Paragraph 1.1)

These outcomes will be delivered through collaborative working across the Executive and beyond government and through the provision of high quality public services

Appendix 2 Self-assessment checklist: effective collaboration (Paragraph 1.3)

This self-assessment checklist will help public bodies develop better practice, procedures and protocols for effective collaboration.

|

Developing effective collaboration: self-assessment |

In place? |

|---|---|

|

Understand the cross-entity environment |

|

|

1 Entities have worked together to understand the common goals and drivers for any proposed collaboration. |

|

|

2 Entities have established and mutually agreed that a collaborative arrangement is likely to present advantages over a single entity approach. |

|

|

Promote cross-entity performance and accountability |

|

|

3 Entities have discussed and agreed on a clear purpose, a coordinated strategy and shared and visible lines of accountability. |

|

|

4 Each party’s expectations, responsibilities and functions have been identified, agreed, understood and documents, including arrangements for funding, monitoring progress and performance reporting. |

|

|

Establish clear roles, responsibilities and governance arrangements |

|

|

5 The parties have agreed and documented accountability arrangements in three dimensions:

|

|

|

6 Appropriate consideration has been given (and action taken) to appointing a lead entity and/or management committee to oversee and drive the partnership and monitor outcomes. |

|

|

7 Appropriate consideration has been given towards establishing formal dispute resolution mechanisms in order to deal effectively with any differences that arise during the course of the partnership. |

|

|

Work towards a shared objective or outcome, while managing shared risks |

|

|

8 The desired objective or outcome of the collaboration has been agreed and clearly documented. |

|

|

9 Funding and accountability arrangements have been discussed, agreed and clearly documented, with a focus on ensuring transparent and appropriate expenditure of public funds. |

|

|

10 Risks associated with the collaboration—including shared risks—have been identified, considered and fairly allocated, and agreement has been reached and documented on how risks will be managed and reported on. |

|

Appendix 3 Suggested agenda for initial partnering meeting (Paragraph 2.6

AGENDA

1. Introductions

It is important not to rush through initial introductions. This is as much about introducing the organisation and its focus and priorities as well as individuals. Understanding each other’s organisation and its possible contribution to the partnership. Who are the best people from which organisation for this partnership and who is best to chair?

2. Objectives and outcomes

Come to the meeting with a draft plan and discuss what success looks like at both the population accountability (PfG outcome) level and local service (performance) level.

3. Timescales

Include key decision-making milestones, such as PfG commitments, budget approvals and potential down-time.

4. Resources

Be clear about which partner is bringing what to the table (financial and non-financial resources). Discuss administrative support available and how much time individual partners can commit (weekly, fortnightly, or monthly). Identify your comparative strengths and which partners have the most effective links with any potential third party advocates.

5. Possible governance structures

What type of collaboration or partnership is planned or would suit the partnership? Is it specified in the funding agreement? What protocols and communication processes will we need to make this work (Memorandum of Understanding?).

6. Evaluation and measuring

Cover outputs and outcomes at both national and local level and which organisation is responsible for capturing which. Discuss and identify public service delivery data available to measure outcomes and whether local partners can help.

7. Sign-offs and wider buy-in

Discuss need to share plans for engaging political leadership and surface any possible challenge. If partnership personnel move on, does the wider organisation know about the collaboration to provide cover and make sure momentum is maintained?

8. Update meetings and liaison points

Agree the update and reporting schedule and how the wider team will keep in touch. All partners allocate a project lead.

Appendix 4 Memorandum of Understanding (MOU) (Paragraph 3.5)

What is a memorandum of understanding?

A Memorandum of Understanding (MoU) is a document that records the common intent and agreement between two or more parties. It defines the working relationships and guidelines between collaborating groups or parties.

Functions of MoUs

MoUs can help clarify roles and responsibilities, intent and goals. An MoU’s content and depth depend on its purpose. For example, if the MoU is to be used to describe the service delivered by one public body to another, it will contain significantly more detail on scope of services than if it is used to describe something less complex, like a working arrangement.

How is an MoU different from a contract and service-level agreement?

MoUs, service-level agreements (SLAs) and contracts are all joint-working agreements, each with different implications and purposes. The key difference between an MoU and a contract is that an MoU is neither a legal document nor legally binding. Therefore the principles within it are not legally binding. It can be terminated without legal consequence in most circumstances. A Service Level Agreement (SLA) focuses solely on measuring performance and quality agreed between both parties. It may be used as a measurement tool as part of a contract or MoU. An SLA would not determine governance arrangements, financial arrangements, contract lengths, etc. Creating an SLA as well as a contract/MoU allows you to revise the SLA without changing the contract. Though the contract may be for five years, the SLA may be reviewed and amended quarterly or yearly.

When to use an MoU?

- MoUs are used when two or more parties wish to collaborate on a project or arrangement but do not want to make the agreement legally binding. Therefore, MoUs are useful when there is a high level of trust between the parties.

- A contract would be used when the relationship between parties needs to be legally binding.

- MoUs are flexible, and can be created and implemented relatively quickly.

- When performing a joint procurement activity, an MoU may be created to define the working relationship between the procuring parties.

- When one party delivers services for another, they may use an MoU if they do not need to create a legally binding contract.

Sources of research

In compiling this Guide, we have drawn on a range of available good practice including:

- Memorandum of understanding guidance: Corporate services productivity programme; NHS: Improvement June 2018

- Working together: A toolkit for campaigns collaboration across the public sector; Government Communication Service; 2016

- What works Scotland, Evidence review December 2015

- Public Sector Governance: Strengthening performance through good governance: Better Practice Guide; Australia National Audit Office; June 2014

- Partnership practice guide; Victoria Council of Social Science; 2011

- Improving the governance of local strategic partnerships; Audit Commission; 2009

- Putting outcomes based accountability into practice; National Children’s Bureau; June 2018

- The 7 stages of partnership development; Mental Health Coordinating Council (Australia)

- Trying Hard is Not Good Enough – How to Produce Measurable Improvements for Customers and Communities; Mark Freidman.

- Group & Organization Management, Vol. 2, No. 4, 419–427; Tuckman, B & Jensen;1977

Acknowledgements

We are grateful to many people for their contributions and input to the research which informed this guide. In particular we wish to record our thanks to:

Brendan McDonnell and Brenda Kent, Community Evaluation NI

Celine McStravick, National Children’s Bureau (NI)

Katrina Godfery, Department for Infrastructure

Lesley McCombe, Department of Justice, Community Safety Division