Internal Fraud

What is internal fraud?

Internal fraud (also referred to as staff fraud or insider fraud) is fraud committed against an organisation by someone employed by that organisation. Internal fraud can range from minor thefts of assets or inflated expense claims up to major diversion of funds, accounting frauds or exploitation of payroll or client data. A person employed by an organisation includes contracted employees, temporary staff, agency workers and contractors.

Why does internal fraud happen?

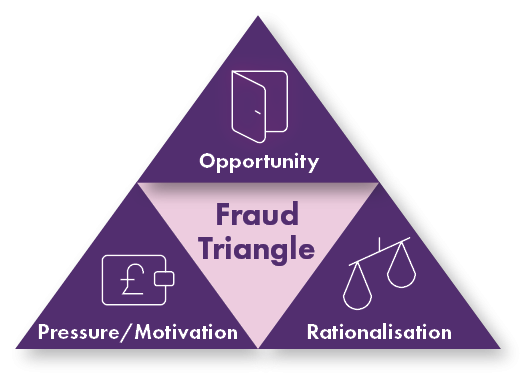

The fraud triangle is used by fraud experts to explain why fraud happens. When the three elements of pressure, opportunity and rationalisation combine, a person may cross the line into fraudulent behaviour. In addition, forensic fraud investigators refer to the 10-80-10 principle whereby:

- 10 per cent of people will never commit fraud;

- 80 per cent of people may commit fraud when the three key elements coincide; and

- 10 per cent of people will actively seek to commit fraud.

So while the vast majority of people are honest and trustworthy, they also have the capacity to commit fraud, given a particular set of circumstances. The challenge for organisations is to minimise the risk of internal fraud by controlling the elements of pressure, opportunity and rationalisation as much as possible.

Opportunity is the most obvious area that organisations can influence, by having in place a sound system of internal controls which operates effectively. However, the actions of organisations can also influence pressure (for example, the expectation to meet challenging and unrealistic targets may cause an employee to commit internal fraud) and rationalisation (for example, an employee who considers themselves to have been unfairly treated by their employer may see that as justification for committing an internal fraud).

Anyone in the organisation presents a potential fraud risk regardless of their position, age, gender or length of service.

Source: Managing the Risk of Fraud (NI):A guide for managers, Department of Finance, 2011

Is internal fraud a risk for NI public sector organisations?

Internal fraud is a real risk within the NI public sector. Under Managing Public Money NI, all actual, suspected and attempted frauds affecting departments and their arm’s length bodies must be reported to the Comptroller and Auditor General (C&AG). In the period from 1st January 2018 to 31st December 2021, 250 cases were notified to the C&AG where the perpetrator was internal to the organisation. Of these cases, 62 were reported as actual frauds. Examples of the types of frauds reported include:

- diversion of funds

- working elsewhere while off sick

- over-claiming expenses

- theft from a client.

Has COVID-19 increased the risk of internal fraud?

The COVID-19 pandemic has increased the risk of internal fraud in a number of ways, for example:

- Furlough may have led to staff shortages in some areas, compromising the application of internal controls.

- Changes in staff deployment may mean people are working in unfamiliar roles without a proper understanding of the procedures and controls which should operate.

- Working from home has now become the norm across many public sector organisations and this may have impacted on systems of internal control. Are controls still operating as they should in a remote working environment?

- Normal channels for staff or third parties to raise concerns about possible fraud risks may not have continued to operate effectively.

- The financial impact of COVID-19 on a household’s income (e.g. due to furlough or redundancy) may mean staff are tempted to make up any shortfall through, for example, false claims for overtime or expenses, aware that normal controls may not be fully operating.

- The pressure to recruit additional staff in certain key areas, in a short timescale, may have led to increased recruitment fraud, e.g. use of fraudulent documentation to support applications.

Trusting but having the appropriate checks and balances in place is not the same as not trusting. It is basic management and governance.

Source: Public Sector Counter Fraud Journal, HMG, Issue 5, June 2020

How can organisational culture help minimise the risk of internal fraud?

Organisational culture is fundamental to minimising the risk of internal fraud. There needs to be a clear message from the top of every organisation that fraud will not be tolerated and will be dealt with effectively when it occurs. But senior managers and Board members must do more than send the right message, they must lead by example. They must behave in an open, honest and ethical way and make clear their expectation that all staff do the same. A positive culture is everyone’s responsibility.

What are the consequences for an organisation if internal fraud risk is not addressed?

If an organisation does not effectively address internal fraud risk, there are a number of potential consequences, including:

- financial loss – the financial impact of internal fraud can be as significant as that of external fraud;

- reputational damage – internal fraud can significantly damage an organisation’s reputation, perhaps more so in the public sector where public money is involved;

- internal impact – the impact within an organisation can be significant, for example by damaging trust and staff morale, and there will also be financial implications in terms of the cost of the investigation and disciplinary process and the recruitment process for a replacement staff member; and

- regulatory implications – organisations may face significant financial penalties if, for example, customer or client data is compromised.

Organisational norms – the way things are done in a business – are an important influence on behaviour. The behaviour of others is an important cue – especially from senior leaders – and unethical behaviour can be contagious.

Source: Rotten apples, bad barrels and sticky situations:an evidence review of unethical workplace behaviour, CIPD, 2019

Structure of the Guide

The Guide sets out the key fraud risks/red flags and mitigating controls under a number of headings:

- General

- Employment application fraud

- Theft

- False claims

- Misuse of official assets

- Manipulation of official systems/processes

- Corruption

- Data/IT related fraud

Further information

The Guide draws on information already in the public domain. You will find links to the sources used, illustrative case examples and a self-assessment checklist towards the end of the Guide. There is also a section on internal fraud risk indicators – the early warning signs of potential internal fraud.

General

|

Fraud Risks / Red Flags |

Mitigating Controls |

|---|---|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

Employment application fraud

|

Fraud Risks / Red Flags |

Mitigating Controls |

|---|---|

|

|

Theft

|

Fraud Risks / Red Flags |

Mitigating Controls |

|---|---|

|

|

|

|

|

|

False claims

|

Fraud Risks / Red Flags |

Mitigating Controls |

|---|---|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

Misuse of official assets

|

Fraud Risks / Red Flags |

Mitigating Controls |

|---|---|

|

|

|

|

|

|

Manipulation of official systems/processes

|

Fraud Risks / Red Flags |

Mitigating Controls |

|---|---|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

Corruption

|

Fraud Risks / Red Flags |

Mitigating Controls |

|---|---|

|

|

Data/IT related fraud

|

Fraud Risks / Red Flags |

Mitigating Controls |

|---|---|

|

|

|

|

|

|

Useful sources

Managing the Risk of Fraud (NI): a guide for managers, Department of Finance, December 2011

Fraud Risk Management: A guide to good practice, CIMA, 2012

Staff Fraud and Dishonesty: Managing and mitigating the risks, CIFAS/CIPD, June 2012

Ongoing Personnel Security: a good practice guide, CPNI, April 2014

Conflicts of Interest: a good practice guide, NIAO, March 2015

Payroll Fraud: guidance for prevention, detection and investigation, NHS, June 2015

Managing Fraud Risk in a Changing Environment, NIAO, November 2015

Managing the Risk of Bribery and Corruption, NIAO, November 2017

HMG Personnel Security Controls, Cabinet Office, May 2018

Rotten apples, bad barrels and sticky situations: an evidence review of unethical behaviour in the workplace, CIPD, April 2019

Raising Concerns: a good practice guide for the NI public sector, NIAO, June 2020

Procurement Fraud Risk Guide, NIAO, November 2020

Employment Screening: a good practice guide, CPNI, August 2021

Case examples

Case example – misuse of official assets:

An employee retained a fuel card for a temporary replacement council vehicle and then made fuel purchases for his own vehicle and for others, amounting to £4,000.

Following concerns that individual budget managers were not properly monitoring fuel card usage, the process was centralised. Centralised monitoring highlighted that purchases of unleaded fuel were being made on a card issued for a diesel vehicle, or for fleet vehicles not in use on the day of fuel purchase.

The employee was dismissed following a disciplinary process and was invoiced for the cost of the fuel fraudulently purchased with the card.

Source: Review into the risks of fraud and corruption in local government procurement, Ministry of Housing, Communities and Local Government (MHCLG), June 2020, Annex 4

Key lesson: Supervisory checks must be in place and operating effectively.

Case example – manipulation of official systems/processes:

A team leader in the Independent Living Service within a local authority purchased over £117,000 worth of items, which were not required by the service/clients, over a seven year period. Concerns were raised by a manager following a budget review. The fraud took advantage of a £300 threshold where orders did not require authorisation, and a particular arrangement with a retailer involving a trade card, where no order went to the supplier.

The concerned manager called in Internal Audit who reviewed the purchases and found items being purchased that were not consistent with the service. The purchases were being resold by the team leader on eBay. The member of staff received a 20-month jail sentence and confiscation order.

Source: Review into the risks of fraud and corruption in local government procurement, MHCLG, June 2020, Annex 4

Key lesson: Management information must be reviewed to detect possible discrepancies.

Case example – manipulation of official systems/processes:

An NHS training co-ordinator was concerned that his boss was hiring a friend to deliver training on suspicious terms which were costing the Trust over £20,000 a year. More courses were booked than were needed and the friend was still paid when a course was cancelled. The co-ordinator saw the friend enter the boss’ office and leave an envelope. His suspicions aroused, he looked inside and saw that it contained a number of £20 notes.

The co-ordinator raised his concerns with a director at the Trust who called in NHS Counter Fraud. The suspicions were right: his boss and the trainer pleaded guilty to stealing £9,000 from the NHS and each received 12 month jail terms, suspended for two years.

Source: Protect (formerly Public Concern at Work)

Key lesson: There should be a clear route for staff to raise concerns about possible internal fraud; concerns should be dealt with effectively.

Case example – theft and manipulation of official systems/processes:

A senior NHS manager stole over £800,000 from his employer over a seven-year period. He set up two companies and sent hundreds of fake invoices to the hospital trust in Essex. Individually, the invoices were all for relatively modest amounts, so the senior manager was authorised to sign them off without further checks. The senior manager had submitted a ‘nil return’ declaration of interests form to his employer.

The senior manager was jailed for two counts of fraud by cheating the Revenue and two counts of fraud by false representation, to serve five years and two months and two years concurrently.

The fraud was uncovered following a data matching exercise under the National Fraud Initiative (NFI), which compared employee details with Companies House records and trade creditor payments.

Source: Media reports, June 2021

Key lesson: Data analytics/data matching should be used to help detect possible internal fraud.

Case example – theft and manipulation of official systems/processes:

A manager in Land and Property Services (LPS) stole £189,000 over a 12-year period. He admitted two counts of fraud by abuse of position and six counts of fraud by false representation. The manager had extensive knowledge of the rates system and part of his middle management role involved processing rates refunds of up to £5,000, which occasionally occurred due to overpayments. He used his knowledge and position to circumvent controls by targeting older closed rate accounts with an outstanding credit balance, where the ratepayer could not be traced and therefore the refund could not be issued, and identified a system vulnerability that enabled him to amend the billing name and address and issue the refund to himself. He was also able to bypass the approval processes and system rules that needed to be satisfied before a refund could be paid. Another member of staff discovered suspicious activity on a rate account and raised concerns. An internal investigation examined over 2,000 refunds involving the manager and found that he had misappropriated over 50 of these, paying them to himself using various means, such as different addresses.

LPS has put in place additional controls to prevent a recurrence of this type of fraud. For example, billing details can now only be amended by staff who have no approval authority, thereby ensuring a separation of duties. More generally, LPS has thoroughly reviewed and strengthened its process checks, quality assurance reviews and monitoring of system access and functionality for users. The manager, described as a “trusted civil servant”, was jailed for a year.

Source: Department of Finance and NI media reports, November 2021

Key lesson: ‘Trust’ must be supplemented by an effective system of internal controls.

Case example – corruption:

Three NHS managers (two project managers employed via an agency and one in-house estates manager) defrauded a Welsh NHS body to the sum of over £822,000. One of the project manager’s responsibilities included sourcing external contractors, approving tenders and quotes, authorising payments of invoices and verifying work completed. A works project was allocated £342,000 by the NHS body and the project manager directed that a specific contracting company be used. An investigation conducted by NHS Counter Fraud Services (CFS) Wales confirmed that the company was actually set up and run by the project manager, with the intention of paying himself for the work he was supposed to be contracting out on behalf of NHS body. In total, the project manager’s company made over £822,000 from NHS contracts.

The project manager used the money to fund a lifestyle of luxury holidays, cars and property purchases. The second project manager knew from the outset that the first project manager was connected to the company, and the estates manager found out sometime later. Both became complicit in the fraud by accepting bribes in the form of envelopes containing cash or cheques, posted to their home addresses. The work that was actually carried out was done to a very poor standard, so the NHS body subsequently had to pay to have it corrected.

In November 2018, the three managers were sentenced to a combined total of 14 years in prison and were subject to confiscation orders.

Source: NHS CFS Wales, November 2018

Key lesson: Agency employees must be subject to the same due diligence and code of conduct requirements as direct employees.

Case example – theft and manipulation of official systems/processes:

In February 2005, the Sports Institute for Northern Ireland (SINI) appointed a Finance and Corporate Services Manager whose responsibilities included accountancy, payroll administration, banking, reconciliations and signing cheques. An office administrator discovered a series of suspicious financial transactions and raised concerns, resulting in an investigation. It found that the manager: had sole responsibility for bank transfers; dishonestly obtained the passwords to the on-line banking system, allowing him to create, authorise and execute payments to the bank accounts of his wife and daughter, disguising them as legitimate salary payments; hid the fraudulent payments in the bank reconciliations which he produced; and made changes to his PAYE records to dishonestly minimise his income tax. In total, the manager was estimated to have stolen over £75,000 in a 10-month period. He received an 18-month prison sentence, suspended for two years.

The investigation identified a number of control weaknesses which allowed the internal fraud to occur, including: a lack of separation of duties; outdated financial procedures; a lack of management supervision; and failings in corporate governance arrangements, in particular poor quality reporting to the Board and ineffective internal audit arrangements.

Source: Internal Fraud in the Sports Institute for Northern Ireland, NIAO, 19 November 2008

Key lesson: Fundamental controls, such as documented procedures, separation of duties and management supervision, must be in place and operating effectively.

Case example – theft and manipulation of official systems/processes:

In August 2003, Ordnance Survey Northern Ireland (OSNI) uncovered an internal fraud which had been perpetrated over a five year period and resulted in a loss to OSNI of almost £71,000. The fraudster, who was a supervisor in Accounts Branch, replaced cash, which had been received from the sale of maps, with cheques to the equivalent value which he had stolen from incoming post. As credit controller, the fraudster created fictitious credit notes to amend customer accounts to the value of the stolen cheques, thereby clearing any outstanding debt. The fraud was discovered when the perpetrator went off on extended sick leave and was unable to cover his tracks.

The fraudster pleaded guilty to stealing cash and falsifying records and was sentenced to twelve months imprisonment, suspended for two years. He was also ordered to repay £30,000. The fraud persisted because of the absence of, or non-compliance with, basic controls. In addition, fraud indicators were missed, for example queries from customers whose accounts had been manipulated.

Source: Internal Fraud in Ordnance Survey NI, NIAO, 15 March 2007

Key lesson: Potential fraud indicators are early warning signs and must be followed up effectively.

Case example – theft

The chair of a Parents Teachers Association (PTA) defrauded the charity of over £35,000 over four years. The fraud was discovered following the appointment of new trustees who uncovered financial irregularities. They discovered that there were no financial controls in place, including no recording of money raised at fundraising events. Funds raised by the charity were also not forwarded to the school at regular intervals. A review of the PTA’s financial records by the Trustees identified a number of failings. The matter was reported to the police who investigated the case.

The fraudster was convicted of five counts of theft and sentenced to two years in jail, suspended for two years, plus 300 hours of unpaid work. The PTA was able to recover £20,000 of the stolen money.

The PTA strengthened its internal controls by implementing formal cash handling procedures, bank signatories, monthly checking of bank statements by the PTA treasurer and regular submission of funds raised to the school.

Source: Case studies of insider fraud in charities, GOV.UK, April 2018

Key lesson: Basic internal financial controls are a fundamental requirement in any organisation, to help prevent internal fraud.

Case example – false qualifications

A senior executive secured a series of high profile posts in the NHS on the basis of a number of false qualifications, including a degree and a Master of Business Administration (MBA). The deception came to light when, during a separate fraud case in which he was acquitted, his various job applications were assessed and there were found to be inconsistencies.

The fraudster admitted deception and fraud, and was jailed for two years. The court estimated that he had benefited by £643,000 as a result of his deception but assessed his available assets at only £97,737. Under the Proceeds of Crime Act 2002, he was ordered to pay this sum within three months, however this confiscation order was overturned on appeal.

Source: Media reports, 2018 and 2020

Key lesson: Effective pre-employment screening must be in place, in particular for senior posts.

Case example – false qualification

A senior manager in an Oxfordshire NHS Foundation Trust was found guilty of fraud after claiming in his job application that he had a degree, even though possessing a relevant degree was not an essential requirement for applicants; those with “at least ten years’ experience in senior management positions within sizable organisations” could apply without one.

The fraud was discovered when all of the Trust’s executive and non–executive directors’ files were being updated in late 2017, as part of the Trust’s duties under the ‘fit and proper persons’ checks. The manager was ordered by the court to complete 30 hours of rehabilitation and 200 hours of unpaid work.

Source: NHS Counter Fraud Authority, January 2020

Key lesson: Implement effective pre-employment screening to detect any fraudulent information provided by candidates.

Case examples – thefts in local councils

In the first case, an audit of a local council revealed that £12,000 cash income from market traders was unaccounted for. Internal control measures had failed. In particular, the audit found: a lack of income and budgetary control by senior managers; a single employee was involved in the collection and lodgement of cash; a lack of written procedures; and no countersigning of income returns. The council was able to offset some of the loss by way of monies due to the employee in question, and recovered the balance from his pension funds.

In a second case, poor internal controls over the purchase of goods for the canteen resulted in a loss of £3,600 to a council. The employee making the purchases, using petty cash, committed fraud by also purchasing items for personal use. The audit found a lack of regular monitoring of purchases and no documented procedures.

Source: Local Government Auditor reports, NIAO, June 2008 and June 2010

Key lesson: Basic controls such as documented procedures and effective supervision are essential, particularly where cash transactions are involved.

Self-assessment checklist

Please note: This checklist is for guidance only and is not intended to be exhaustive. It focuses on the key good practice standards, and should be considered in conjunction with the more detailed mitigating controls listed in the main sections of this Guide. It can be completed and reviewed/updated periodically to provide a degree of assurance in relation to your organisation’s exposure to internal fraud risks.

|

Good practice standard |

Yes / No |

Action required |

|---|---|---|

|

1. General |

||

|

1.1 Our organisation has a zero tolerance approach to fraud and corruption that is communicated to all staff in an anti-fraud policy, endorsed at a senior level. All staff are aware of their role in relation to fraud prevention. |

||

|

1.2 There is clear commitment from senior management and the Board that fraud will not be tolerated. |

||

|

1.3 We have designated a senior manager with lead responsibility for fraud prevention/counter fraud arrangements within our organisation. |

||

|

1.4 Our line managers are aware of their key role in reducing the risk of internal fraud through effectively supervising and supporting staff. |

||

|

1.5 We have a code of conduct which clearly defines acceptable behaviour for employees. All staff are required to sign up to this. |

||

|

1.6 There are arrangements in place for reporting and addressing conflicts of interest, including a register of interests. Staff are made aware of the need to declare potential conflicts of interest. |

||

|

1.7 Our organisation maintains a register of gifts and hospitality. Staff are aware of the need to register any gifts and hospitality received. |

||

|

1.8 We have a fraud risk assessment in place which considers internal fraud risks and is reviewed and updated regularly. We are alive to the potential indicators of internal fraud. |

||

|

1.9 We have updated our fraud risk assessment in light of the increased risk of internal fraud due to the impact of COVID-19 on working arrangements. |

||

|

1.10 We have a sound system of internal controls in place, including separation of duties, staff rotation, effective supervision etc. Controls are regularly tested. |

||

|

1.11 We recognise that trust is not a control. |

||

|

1.12 Our organisation has an internal raising concerns policy and procedures in place. These are accessible to all staff and offer a choice of reporting routes. |

||

|

1.13 We encourage and support staff to raise concerns about possible internal fraud. |

||

|

1.14 All staff receive fraud awareness training, both at induction and on an ongoing basis. Targeted training is provided to staff in higher risk roles, such as finance and procurement. |

||

|

1.15 We respond effectively when an internal fraud is discovered, in accordance with our fraud response plan. |

||

|

1.16 We report appropriately on frauds internally, and report externally as required by Managing Public Money Northern Ireland or as advised by the Local Government Auditor. |

||

|

1.17 We recognise the importance of good staff morale in minimising the risk of internal fraud, and seek to create a positive, supportive working environment. |

||

|

1.18 We recognise the negative impact that COVID-19 working arrangements may have had on staff morale and seek to mitigate this through regular team contact and reinforcement of culture/internal control messages. |

||

|

2. Employment application fraud |

||

|

2.1 We implement a sound system of pre-employment screening to minimise the risk of fraudsters entering our organisation. We recognise that the Baseline Personnel Security Standard is the minimum for government employees. |

||

|

2.2 We ask prospective employees to sign a declaration that all information provided on their application is true and accurate. |

||

|

2.3 We consider using targeted checks for specific higher risk posts. |

||

|

2.4 We ensure there is clarity about responsibility for pre-employment checks when employing agency staff. |

||

|

3. Theft |

||

|

3.1 We ensure separation of duties in high risk areas such as finance, to prevent diversion of funds. |

||

|

3.2 We are mindful of the fraud risk indicators which could indicate theft by an employee. |

||

|

3.3 We maintain up-to-date asset registers and perform regular spot checks. |

||

|

3.4 We have robust inventory systems in place, including clear separation of duties. |

||

|

4. False claims |

||

|

4.1 We have clear guidance on what can be properly claimed regarding travel and subsistence, working hours and overtime. |

||

|

4.2 We have robust authorisation procedures in place. Potential conflicts of interest are properly managed. |

||

|

4.3 We use the appropriate counter fraud declaration on internal claim forms. |

||

|

4.4 We have clear rules around secondary employment. |

||

|

5. Misuse of official assets |

||

|

5.1 We require employees to declare any business interests or additional employment they may have. |

||

|

5.2 We ensure separation of duties in relation to supplies. |

||

|

5.3 We have effective systems for monitoring the use of official assets. |

||

|

5.4 We tightly control the issue and use of procurement cards and reconcile expenditure to card issuer statements. |

||

|

6. Manipulation of official systems/processes |

||

|

6.1 We have fundamental internal controls in place, including separation of duties, rotation of staff, supervisory checks and proper authorisation of changes to standing data. |

||

|

6.2 We recognise the importance of complete documentation and a full audit trail. |

||

|

6.3 We ensure that conflicts of interest are declared and properly managed, to avoid any perception of nepotism or favouritism. |

||

|

6.4 We make proactive use of management information and data analytics to detect anomalies and inconsistencies, which could indicate internal fraud. |

||

|

7. Corruption |

||

|

7.1 We have a clear statement of ethical values for our organisation and consider bribery and corruption risks as part of our fraud risk assessment. |

||

|

7.2 We have comprehensive policies covering conflicts of interest and gifts and hospitality, to avoid any uncertainty as to what is acceptable. |

||

|

7.3 We raise awareness of bribery and corruption risks as part of fraud awareness training for all staff. |

||

|

8. Data/IT related fraud |

||

|

8.1 We have a comprehensive data/IT policy in place which includes defined roles and responsibilities. |

||

|

8.2 We ensure that staff access rights to sensitive data/IT systems are regularly reviewed, and updated/amended as appropriate. |

||

|

8.3 We ensure there is a full audit trail in relation to data being processed, which is periodically reviewed by management to identify any suspicious activity. |

||

|

8.4 We have reassessed internal data/IT fraud risks in light of revised working arrangements due to the COVID-19 pandemic. |

||

|

8.5 We have a social media policy in place which highlights the risks of staff posting information about their employment online, thereby leaving them open to possible undue influence by fraudsters. |

Internal Fraud Risk Indicators

|

Organisational Indicators |

Operational Indicators |

Personal Indicators |

|---|---|---|

|

|

|