Abbreviations

CFF Common Funding Formula

CYPS Children and Young People Services

DARS Dispute Avoidance and Resolution Service

Department Department of Education

EA Education Authority

EMS Education Management System

ETI Education and Training Inspectorate

GMI Grant Maintained Integrated School

GTCNI General Teaching Council for Northern Ireland

HEIs Higher Education Institutions

HSCTs Health and Social Care Trusts

NICCY Northern Ireland Commissioner for Children and Young People

PHA Public Health Authority

PLP Personal Learning Plan

SEN Special Educational Needs

SEND Special Educational Needs and Disability

SENDO Special Educational Needs and Disability (Northern Ireland) Order

SENCO Special Educational Needs Co-ordinator

SIMS Schools Information Management System

VGS Voluntary Grammar School

Key Facts

67,224 children with reported special educational needs in 2019-20

19.3% percentage of the school population with reported special educational needs in 2019-20

19,200 children with a statement of special educational needs in 2019-20

£311m spent by the Education Authority on children with special educational needs in 2019-20

36% percentage increase in children with a statement of special educational needs in the past nine years

85% percentage of statements of special educational needs issued outside the 26 week statutory limit in 2019-20

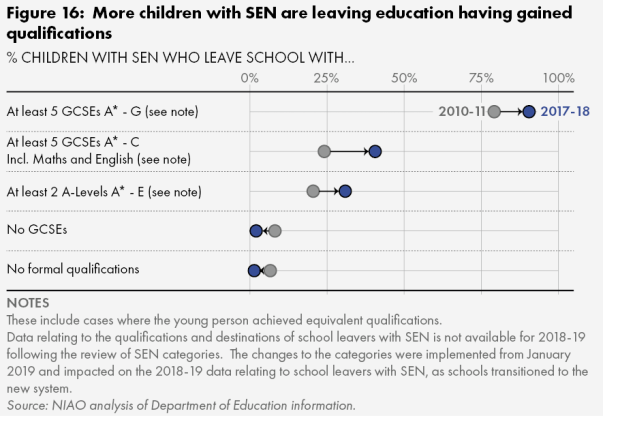

90.5% percentage of children with special educational needs leaving school with at least 5 GCSEs A*-G in 2017-18

13 years number of years that have passed since the Department of Education began a review of special educational needs, at a cost of nearly £3.6 million. It is still not complete.

Executive Summary

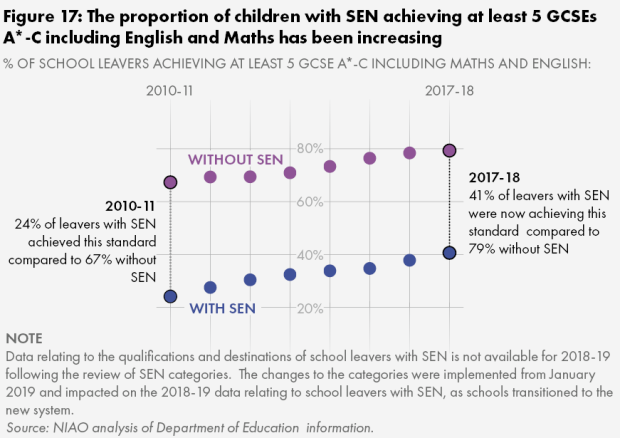

1. On 27 June 2017, we published our Special Educational Needs (SEN) report. The report highlighted that the number of children with SEN and the associated costs were continuing to rise. Whilst the educational achievements of children with SEN were improving, there had been no strategic evaluation of the support provided to these children to ensure the best possible outcomes. Our report also highlighted inconsistencies in the identification of children with SEN and unacceptable delays in the statementing process.

2. We made 10 recommendations (see Appendix 1) and concluded that neither the Department of Education (the Department) nor the Education Authority (EA) could demonstrate value for money in terms of economy, efficiency or effectiveness in the provision of support to children with SEN in mainstream schools.

3. This report presents the findings of our impact review. The primary objective of this latest review was to assess the degree of progress made by the Department and the EA in addressing the recommendations for improvement which had been made, and to consider other developments in this area.

4. To address our recommendations the Department set up a Programme Board, a number of Project Teams and Action Plans. This impact review found that actions have been taken to progress all of the recommendations from our previous report, however in our opinion none have been fully implemented and work remains to be done. Whilst the Programme Board remains in place, many of the Project Teams and Action Plans have now been closed. The Department must ensure that the Programme Board continues to drive forward progress on addressing the issues identified and recommendations made, ensuring no momentum is lost.

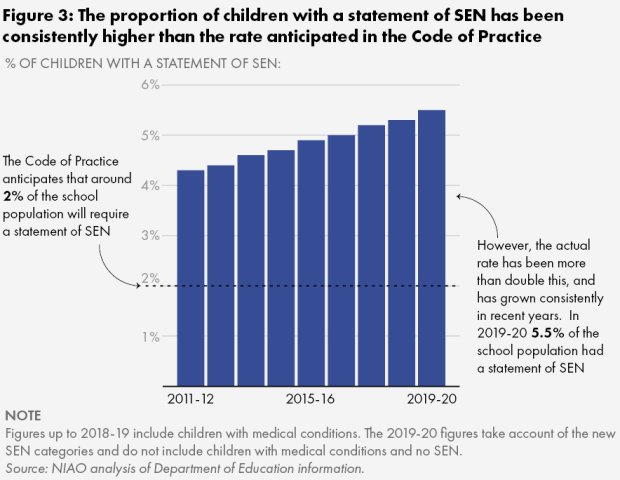

Impact review key findings

5. In 2019-20, 67,224 children were reported as having SEN (with or without a statement). As we previously reported, the Department’s Code of Practice on the Identification and Assessment of Special Educational Needs anticipates that only about two per cent of the school population should require a statement of SEN. However, 19,200 children had a statement of SEN in 2019-20. That is 5.5 per cent of the school population.

More still needs to be done to ensure schools are applying a clear and consistent approach to identifying and providing for children with SEN

6. The importance of early identification of a child’s needs and appropriate intervention is widely recognised. The sooner a child’s needs are identified and appropriate support put in place, the more responsive the child is likely to be. The Department has reminded schools of the requirement to adopt a consistent approach to the identification, assessment and provision made for all children with SEN. However, there is no evidence that this requirement is being adhered to in all schools. Furthermore, a lack of early identification and intervention has again been highlighted recently by the Commissioner for Children and Young People (NICCY). In our view, the Education and Training Inspectorate (ETI), at the direction of the Department, should assess whether schools are applying a clear and consistent approach to identifying and providing for children with SEN.

Significant delays in assessing and providing for children persist

7. As part of this review we sought details on how many children are waiting to access pupil support services at stage 3 and how long it takes for them to access the necessary support following their assessment by the Educational Psychologist. The EA advised that each of the services has a different way to quantify service capacity and average response time. EA figures show that the waiting list for some of these services can be very long and indications are that demand for stage 3 services far exceeds supply. Consequently, many children are waiting to access these services.

8. Proactive management and monitoring of the Statutory Assessment process is essential to prevent any unnecessary delays, however we found there to be a lack of routine management information and monitoring of performance against the 26 week Statutory Assessment timeframe within the EA. We previously reported that in 2015-16, 79 per cent of new statements were issued outside the 26 week statutory limit. It is disappointing to find that performance has further deteriorated, with 85 per cent of all assessments exceeding the 26 week statutory timeframe in 2019-20. We also found that the start date on the system for measuring compliance with the 26 week statutory timeframe is not being accurately or consistently recorded. Consequently, the data currently held by the EA with regards to performance against the 26 week timeframe is not accurate and performance could be worse than that reported.

There is a need for an urgent overhaul of the SEN policies, processes and procedures

9. The number of appeals against the EA’s decisions is rising, primarily as a result of the EA’s refusal to conduct a Statutory Assessment or reassess. We are concerned by the number of cases which the EA concedes prior to Tribunal hearing. Decisions made by the EA in relation to SEN should be robust and able to withstand challenge. In our opinion, the number of cases conceded, and the number which are found in favour of the parent or carers when they do proceed to Tribunal, raises questions as to whether the processes and procedures followed by the EA in relation to SEN are fit for purpose. There is a clear need for an urgent review and overhaul of the SEN processes in place within the EA. This should include the provision of reliable performance management information which should be reported and monitored on a regular basis by both the EA and the Department.

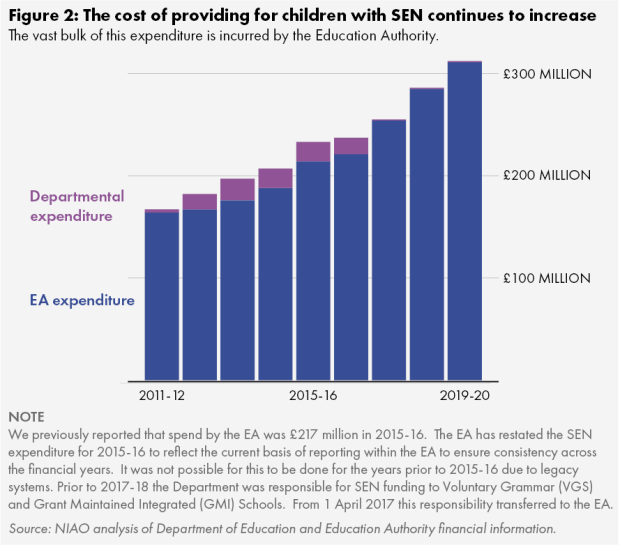

The cost of providing for children with SEN continues to rise

10. Annual expenditure on SEN is increasing and in 2019-20 was £312 million. Of this, £311 million is EA expenditure, including £95 million on classroom, general and supervisory assistants. The EA is now able to identify spend on most SEN services and the reporting issues associated with the legacy financial systems are no longer an issue. However, in our opinion, the current funding of SEN services is not financially sustainable. There is a need for a fundamental review to consider the effectiveness of the funding allocated to all stages of the SEN process to ensure the needs of children, with or without a statement, are met. This requires an evidence base as to which types of support have the best outcomes for children to ensure resources are used to best effect. It should also include assessing the potential impact of directing more resources to support children without a statement, in an effort to maximise the effectiveness of early intervention measures, which might reduce the need for statementing.

More still needs to be done to monitor and evaluate the effectiveness of the support provided

11. As we previously reported, we recognise that measuring progress will be different for each child. Progress may involve closing the attainment gap between the child and his or her peers, or could involve an improvement in social or personal skills. Whatever the outcome, it is important that progress is regularly monitored to ensure the best results are achieved for each child. In our view, the ETI can play a significant role in monitoring and evaluating provision for SEN. It is disappointing that the action short of strike has prohibited the ETI from carrying out an evaluation of SEN provision in mainstream schools. There remains a need to evaluate the provision for children with SEN in primary and post primary schools, identifying strengths and weaknesses in the current provision across Northern Ireland.

12. There is a recognition within the EA that more needs to be done to develop, collate and evaluate data on pupil outcomes, however this is not yet available. Consequently, the effectiveness of the various types of support provided to children has not yet been evaluated and there is no evidence that the support is adequate or positively impacts on outcomes for children. Nor is there any evidence base as to which types of support are the most appropriate or effective. There remains an urgent need for the Department and the EA to evaluate the support provided to children with SEN in terms of the progress they make. This will enable the Department and the EA to make informed decisions and focus resources on the types of support which maximise progress and achieve the best outcomes.

Current developments

13. The Special Educational Needs and Disability (SEND) Act (Northern Ireland) 2016 was passed in the Assembly in January 2016. This is the first element in the Department’s new SEN Framework. The Framework will also include new SEN Regulations and a new SEN Code of Practice. At the time of our previous report the Department intended to begin implementing the new SEN Framework during the 2018-19 academic year. However, due to the suspension of the NI Assembly the presentation of the Regulations was not possible. The Department has worked with the Departmental Solicitor’s Office to make some changes to the draft Regulations and intends to commence the consultation on the draft Regulations and Code of Practice during autumn 2020, subject to Ministerial Approval.

14. In 2018-19 the Department established an Education Transformation Programme in order to review aspects of the existing education system, identify where improvements could be made, develop policy and operational proposals to transform the education system and deliver a managed programme of transformation for the benefit of and responsive to the needs of children and young people. Several projects related to SEN commenced under the Education Transformation Programme including:

- The SEN Learner Journey: this project aims to transform the communication and engagement with learners, their parents or carers and relevant stakeholders. The project will seek to maximise opportunities for effective digital case management and information sharing, at all stages of the SEN process, while protecting data access. It also aims to improve awareness of, and confidence in, the SEN processes.

- A review of pupil support services: this project is reviewing and aiming to develop improved frameworks for a range of pupil support services. There is a recognition by the Department and the EA that there is a need to simplify access arrangements to services; enhance the visibility of services; and enable access to earlier interventions that have a robust evidence base in terms of effectiveness and pupil outcomes. The overall aim of the project is to enhance the provision for children with SEN throughout Northern Ireland.

- Common Funding Scheme: this project is reviewing the current funding arrangements for schools with a view to developing evidence based and fully costed options to make the funding arrangements more effective. Funding for SEN will be considered as part of this project.

Whilst the Education Transformation Programme has been temporarily suspended due to the wider COVID-19 pandemic pressures, the EA is proposing a SEN Strategic Programme which will include taking forward a number of SEN related projects, including the SEN Learner Journey and the review of pupil support services.

15. In recent months the EA has undertaken an internal audit of practice in Special Education across the EA and has made a number of recommendations for improvement. The audit, its associated recommendations and the subsequent scrutiny by the Education Committee are to be welcomed. We are encouraged by the actions now taken by the EA to reduce the backlog of open cases exceeding 26 weeks, with particular focus on the longest standing cases. In addition, the EA are working to improve the management information available to enable tracking of individual cases; collation of data in relation to the number of statements being completed each month and monitoring against the 26 week statutory timeframe. It is however disappointing that neither the Department nor the EA acted sooner, given the significant delays in the Statutory Assessment process have been widely reported in the media over recent years and also highlighted in our 2017 report.

16. In response to the COVID-19 pandemic, the EA introduced a number of short term measures with effect from 23 March 2020. These measures were in line with government guidance to ensure the EA continued to deliver essential education and support services. Special schools remained open for pupils while children with a statement of educational needs, with no viable alternative, could discuss arrangements with their school to determine if the school could provide a safe environment. Children with SEN but no statement were to be home schooled unless they fell into other categories of vulnerabilities. Arrangements were put in place for children, families and schools to be able to contact pupil support services via telephone or email for support and advice. Many of the services developed online resources to provide support. While services have continued to operate in a limited way, aspects of practice requiring face-to-face engagement in a school or home environment have not been possible.

Overall conclusion on value for money

17. It is over thirteen years since the Department began a review to address a range of issues including the increase in the number of children with SEN, and the inconsistencies and delays in identification, assessment and provision. To date the Department has spent more than £3.6 million on the review which is not yet complete.

18. Whilst it is evident that work is underway to address our recommendations, the significant issues identified in our 2017 report persist. In the absence of any meaningful assessment or inspection there is no evidence that schools are identifying children with SEN in a consistent and timely way. Delays throughout the SEN process persist and the support provided has not been evaluated to assess its effectiveness. We remain of the view that the Department and the EA cannot demonstrate value for money in the provision of support to children with SEN. In our view there is a need for a systemic review of the SEN policies, processes, services and funding model to ensure the provision is sufficient to meet the needs of all children with SEN.

Part One: Introduction and Background

1.1 A child has special educational needs (SEN) if he or she has learning difficulties and is assessed as requiring special help. The term ‘special educational needs’ is defined in legislation as ‘a learning difficulty which calls for special educational provision to be made’. A learning difficulty means that a child has significantly greater difficulty in learning than the majority of children of his or her age, and/or has a disability which hinders his or her use of everyday educational facilities. Special educational provision means educational provision which is different from, or additional to, the provision made generally for children of comparable age.

1.2 The Education (Northern Ireland) Order 1996, the Special Educational Needs and Disability (Northern Ireland) Order 2005 and the Special Educational Needs and Disability Act (Northern Ireland) 2016 provide the primary legislation for the SEN Framework. The majority of the provisions in the 2016 SEND Act have yet to be commenced, as they are dependent on the SEN Regulations being made by the Assembly. Statutory responsibility for securing provision for children with SEN rests with schools and the EA. They must identify, assess and, when appropriate, make provision for children with SEN. The Special Educational Needs and Disability (Northern Ireland) Order 2005 (SENDO) brought in a strengthened duty to educate children with SEN in mainstream schools. The 2016 SEND Act requires the Board of Governors of a school to ensure that ‘…the teachers in the school take all reasonable steps to identify and provide for those (pupils attending the school) who have special educational needs’.

1.3 The Department has no role in the identification and assessment of a child’s SEN nor any power to intervene in the process, however, it does have a policy role and provides funding to the EA. The Education and Training Inspectorate (ETI) provides inspection and evaluation services for the Department. As part of the school inspection process, the ETI evaluates the provision for children with SEN and aims to promote the dissemination of good and innovative practice.

1.4 As we previously reported, pupils with SEN are increasingly being educated in mainstream schools, including Learning Support Centres attached to mainstream schools. In 2019-20, 70 per cent of pupils with a statement of SEN attended mainstream schools.

All mainstream schools have a SEN Co-ordinator

1.5 In all mainstream schools a designated teacher should be appointed as the SEN Co-ordinator (SENCO). The SENCO is responsible for:

- the day-to-day operation of the school’s SEN policy;

- responding to requests for advice from other teachers;

- co-ordinating SEN provision;

- maintaining a SEN register;

- liaising with parents or carers of children with SEN;

- establishing the SEN in-service training requirements of staff, and contributing as appropriate to their training; and

- liaising with external agencies.

The 2016 SEND Act will place a new statutory duty on schools to appoint a teacher in their school to the role of Learning Support Co-ordinator, the new name for SENCO.

A Code of Practice sets out a staged approach to identifying and assessing children with SEN

1.6 The Department’s current Code of Practice on the Identification and Assessment of Special Educational Needs (the Code of Practice) produced in 1998, is based on legislation and is a guide for schools and the EA. The Code of Practice sets out a five stage approach to the identification of children with SEN, the assessment of their needs and the making of whatever special educational provision is necessary to meet those needs (see Figure 1).

Figure 1: The five stage approach to the identification of SEN as per the Code of Practice

Stage 1:

Teachers identify and register a child’s special educational needs and, consulting the school’s SENCO, take initial action.

Stage 2:

The SENCO takes lead responsibility for collecting and recording information and for co-ordinating the child’s special educational provision, working with the child’s teachers.

Stage 3:

Teachers and the SENCO are supported by specialists from outside the school.

Stage 4:

The EA considers the need for a Statutory Assessment and, if appropriate, makes a multi-disciplinary assessment.

Stage 5:

The EA considers the need for a statement of SEN; if appropriate, it makes a statement and arranges, monitors and reviews provision.

Source: Department of Education.

1.7 The first three stages are based in the school, calling as necessary on external specialists at stage 3; at stage 4 the EA is responsible for undertaking a Statutory Assessment; and at stage 5 the EA is responsible for the additional provision outlined in any statement issued.

1.8 A statement of SEN (a statement) is a document that sets out a child’s needs and the special help required. The EA will make a statement when it decides that the help needed by a child cannot reasonably be provided within the resources normally available to a school.

Expenditure on SEN continues to increase year on year

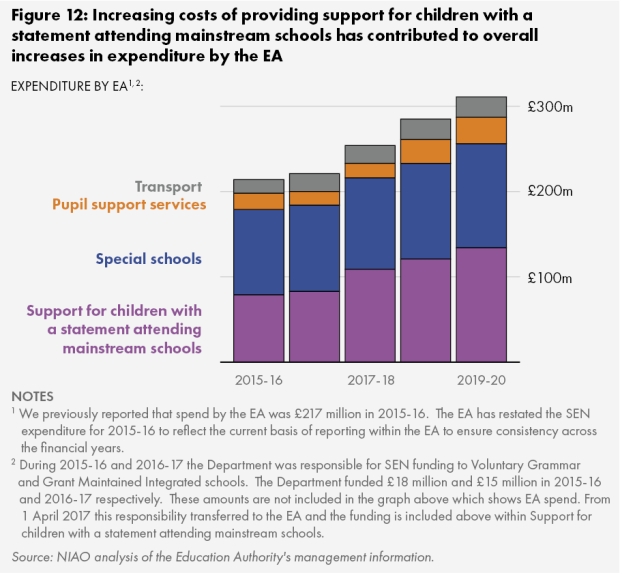

1.9 This impact review found that expenditure on providing for children with SEN continues to increase (see Figure 2). During 2019-20, expenditure on providing services for children with SEN was £312 million (£233 million in 2015-16). Of this, £311 million (£214 million in 2015-16) was EA expenditure.

The percentage of children with a statement is still higher than the Department anticipates

1.10 According to the Code of Practice, the proportion of children with SEN will vary from area to area and from time to time, but it anticipates that for only about two per cent of the school population should the child’s needs be such as to require a statement of SEN. Currently 5.5 per cent of the school population has a statement (see Figure 3 and Appendix 5).

1.11 During 2017-18 a full review of SEN categories was undertaken and a new list of SEN categories and associated descriptions has been created (see Appendix 2). Guidance was issued to highlight the changes which were implemented from January 2019. In addition, a list of medical categories, with associated descriptions, was provided to allow the creation of a Medical Register. All schools now have a SEN Register and a separate Medical Register. Those pupils with a medical diagnosis and no SEN should be on the new electronic Medical Register only. If a pupil has SEN and no medical diagnosis they should be on the SEN Register only. Those pupils with a medical diagnosis and a SEN (related or not) should be recorded on both. The data associated with the new categories was captured in the October 2019 annual school census. These changes have reduced the number of pupils recorded on the SEN Register (see Appendix 5).

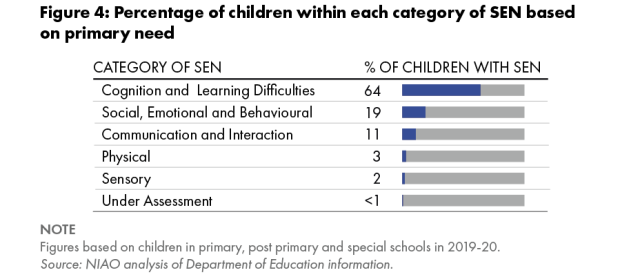

1.12 In Northern Ireland, the majority of children with SEN have cognitive and learning difficulties (see Figure 4).

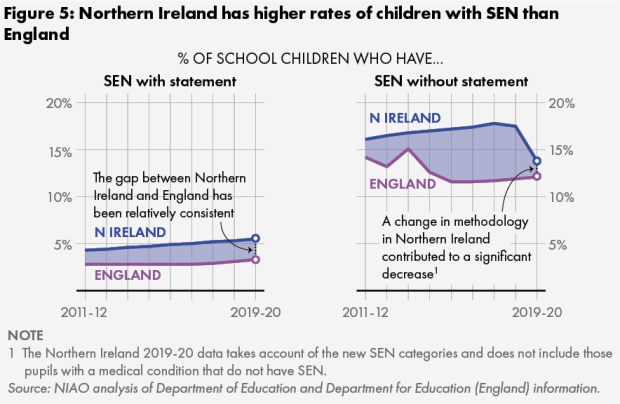

The percentage of children with SEN is higher in Northern Ireland than in England

1.13 In Northern Ireland, the percentage of children with SEN without a statement has decreased from 16.1 per cent in 2011-12 to 13.8 per cent in 2019-20 as a proportion of total school enrolments, while the percentage of children with a statement has increased from 4.3 per cent in 2011-12 to 5.5 per cent in 2019-20 (see Figure 5 and Appendix 5). In England, the percentage of children with SEN without a statement decreased, from 17.8 per cent in 2011 to 12.1 per cent in 2020 and the percentage of children with a statement remained constant at 2.8 per cent between 2007 and 2018, after which it increased to 3.3 per cent in 2020. According to the Department for Education (England), the implementation of the SEND reforms in September 2014 led to more accurate identification, resulting in a steep decline in the number of children with SEN.

The Department’s review of SEN began in 2006 and is still not complete

1.14 The Department commenced a review of SEN in 2006, in response to a number of concerns. The review aimed to address the bureaucracy attached to the SEN Framework, the increasing number of children with SEN and inconsistencies and delays in assessment and provision. Following a period of consultation and extensive feedback on the new proposals, in 2012 the Minister for Education presented the final proposals to the Executive who agreed to proceed with the proposals and the preparation of the required implementing legislation. The Special Educational Needs and Disability (SEND) Act (Northern Ireland) was subsequently passed in the Assembly in January 2016. Significant policy changes include a reduction in the SEN stages from five to three (see Figure 6), each child with SEN to have a Personal Learning Plan replacing the current Individual Education Plan, and children over 16 to be given their own rights. There is to be a new independent mediation service and increased co-operation between the Health and Education sectors. A new independent Dispute and Resolution Service (DARS) has been in place since September 2019.

Figure 6: The current five SEN stages in the Code of Practice and the proposed changes

Stage 1 – teachers identify and register a child’s special educational needs and consulting the school’s SENCO, take initial action.

Stage 2 – the SENCO takes lead responsibility for collecting and recording information and for co-ordinating the child’s special educational provision, working with the child’s teachers.

New Stage 1

- Personal Learning Plan required

- Schools deliver special educational provision

Stage 3 – teachers and the SENCO are supported by specialists from outside the school.

Stage 4 – the EA considers the need for a Statutory Assessment and, if appropriate, makes a multi-disciplinary assessment.

New Stage 2

- Personal Learning Plan required

- Schools deliver special educational provision plus external provision

Stage 5 – the EA considers the need for a statement of SEN; if appropriate, it makes a statement and arranges, monitors and reviews provision.

New Stage 3

- Personal Learning Plan required

- Both school and EA special educational provision and, as appropriate, any treatment or service identified by the Health sector

Source: NIAO based on Department of Education documentation.

1.15 The SEND Act (Northern Ireland) 2016 is the first element of the new SEN Framework being developed by the Department. This Act will be supported by new SEN Regulations and a new SEN Code of Practice. At the time of our previous report the Department intended to begin implementing a new SEN Framework during the 2018-19 academic year. However, due to the suspension of the NI Assembly the presentation of the Regulations was not possible. The Department has worked with the Departmental Solicitor’s Office to make some changes to the draft Regulations and intends to commence the consultation on the draft Regulations and Code of Practice during autumn 2020, subject to Ministerial Approval.

1.16 To date, the Department has spent more than £3.6 million on the review which has been ongoing for over thirteen years and the outworking of the process is not yet complete.

Scope of this impact review

1.17 This impact review considers the actions taken and progress made by the Department and the EA in response to the recommendations in our 2017 report (see Appendix 1).

1.18 We have also provided an update on relevant statistics including the number of children with SEN (with and without a statement), spend on the various types of support for children with SEN, the timeframe for assessing and issuing statements and the reason for delays. We have also considered developments in the area. The report is structured as follows:

- Part Two reviews the progress made in early identification and intervention;

- Part Three considers the costs and funding arrangements for SEN provision; and

- Part Four examines the progress made in monitoring and evaluating the impact of SEN provision.

1.19 Our study methodology is at Appendix 4.

Part Two: Early identification and intervention

2.1 Our 2017 report noted that the importance of the early identification of a child’s needs is widely recognised and was a key theme emerging from the Department’s review of SEN. Some incidences of SEN can be identified at a young age, however in other cases the difficulties may only become evident as the child develops. At whatever age the need arises, the sooner it is identified and appropriate support is put in place, the more responsive the child is likely to be.

2.2 However, it was evident that there were variations in the methods used to identify children requiring additional support. We concluded that in the absence of the application of a standardised approach by schools, children throughout Northern Ireland with similar needs may not be treated equitably and may not have access to the same provision within the same timeframe. We recommended that the Department and the EA should ensure that schools apply a clear and consistent approach to identifying, and providing for, children with SEN (Recommendation 1).

More still needs to be done to ensure schools are applying a clear and consistent approach to identifying and providing for children with SEN

2.3 In June 2018 the Department reminded schools that they have a legal duty, under Article 4 of the Education (Northern Ireland) Order 1996, to have due regard to the provisions of the SEN Code of Practice and its Supplement and that the Board of Governors and school leadership should ensure that they adopt a consistent approach to the identification, assessment and provision made for all children with SEN. The Department asked the EA to remind schools about the need to have regard to the existing SEN Code of Practice during their training sessions to prepare schools for the new SEN Framework.

2.4 As noted in Paragraph 1.11, a review of the SEN categories was undertaken in 2017-18 and the Department issued revised SEN and Medical Category information and guidance to all schools. The purpose of this guidance was to reinforce the process for placing children on the SEN Register, to introduce the revised SEN categories and associated descriptions and to promote a common understanding of what is meant by a particular SEN category. Separate Medical Diagnoses (including physical conditions) categories and relevant associate descriptions were introduced. The revised SEN categories are at Appendix 2. All schools were provided with training on the new SEN and Medical categories. The Department made the corresponding software changes to the School Information Management System (SIMS) IT system. In addition to their SEN Register, schools now have a new electronic Medical Register. The October 2019 census figures show a reduction in the number of children recorded as having SEN without a statement and the Department has attributed the decrease to the application of the new guidance.

2.5 The Department commissioned the ETI to carry out an evaluation of the impact of SEN provision in mainstream schools and support on pupil outcomes, with a particular focus on effective early intervention strategies. The ETI selected twenty primary schools and ten post-primary schools which had been previously evaluated as having highly effective provisions for pupils with SEN. In May 2019, the ETI published its Report of a survey of SEN in mainstream schools, discussing effective practice for SEN in the schools and providing relevant case studies. The Department told us that as a means of sharing best practice, the report was disseminated to all schools and followed up with complementary video sessions involving some of the schools surveyed.

2.6 The ETI reported that the available data from school admissions shows a continuing rise in the number of pupils with SEN and that the needs of pupils in mainstream schools are more complex, with an increasing number starting school with under-developed communication, social and self-help skills. The ETI highlighted that some schools are experiencing very significant challenges to managing their budgets, particularly with regard to SEN. The schools have developed a comprehensive variety of systems and strategies to provide competently for these pupils and identified the common factors which have provided high quality provision for pupils with SEN (see Appendix 3).

2.7 The Department has reminded schools of the requirements and the ETI report serves to highlight and share the good practice found in schools with a highly effective provision for pupils with SEN. However, a lack of early identification and intervention has again been highlighted recently by the Commissioner for Children and Young People (NICCY). In our view, in the absence of monitoring or a full evaluation by the ETI, there is no evidence that schools are applying a clear and consistent approach to identifying and providing for children with SEN.

Training and developing staff expertise continues

2.8 Our 2017 report noted that good, regular and practical training in SEN identification and provision is important for all staff in mainstream schools, not just SENCOs. We found a general consensus that there was not enough focus on SEN as part of initial teacher education and that all newly qualified teachers need to be able to identify SEN issues, and know how to deal with them, as soon as they start teaching.

2.9 We recommended that the Department and the EA should ensure that all teachers, including those studying for their teaching qualification, receive appropriate training so they are able to identify children with SEN and take the necessary action to provide support to them (Recommendation 2).

2.10 This impact review found that the EA developed a compendium of training for schools. This training compendium is updated annually and communicated to schools. The training programme focuses on a number of SEN areas. Between 2017-18 and 2019-20, the Department provided £4.6 million for the EA’s SEND Implementation Team. The largest element of this funding was to cover a training package for schools (Principals and SENCOs) and EA staff on the new SEN Framework with a focus on the new SEN Regulations and new Code of Practice. Nearly 960 school Principals and SENCOs were trained by the EA, of which 99.9 per cent rated the training as satisfactory to excellent. In 2020-21, a further £2.5 million has been allocated to the EA for implementation of the new SEN Framework. The Department told us this will allow training for schools and EA staff to continue and will include training on the new electronic Personal Learning Plan which will be required for all pupils on a school’s SEN Register.

2.11 The Department told us that all NI Higher Education Institutions (HEIs) offering Initial Teacher Education provide compulsory modules which specifically relate to SEN and Disability Awareness within their Bachelor of Education and Post-graduate Certificate in Education programmes. The precise content of courses, and individual modules within them, is determined by the HEIs. During 2019 the EA engaged with the HEIs, exploring how student teachers were taught to recognise pupils with SEN and take necessary action to support them. The EA found there was a range of differences and disparities in the approaches adopted by the individual HEIs, including:

- course design, duration and content;

- opportunities for SEN placements;

- optional modules; and

- method of delivery and assessment.

2.12 During June 2018 the EA engaged with the General Teaching Council for Northern Ireland (GTCNI) to ensure that teacher competences took account of SEN. These teacher competences are being reviewed as part of the programme of work being taken forward through the Learning Leaders Strategy. The Department also told us that the GTCNI has confirmed that when assessing the evidence documents submitted by the HEIs, its Accreditation Committee gives particular attention to how HEIs are preparing their student teachers and helping them to become competent in dealing with SEN. The GTCNI has also agreed that robust assessment processes would be put in place to ensure the standards of teaching qualifications accepted for registration from other jurisdictions are as comparable as possible with the NI based initial teacher training.

2.13 During this review we became aware that children with SEN are nearly twice as likely to be suspended from school as those without SEN. The Department was unable to provide any insight as to why this may be the case, however the review by NICCY suggested it could be linked to a lack of capacity in schools to adequately manage the behavioural issues which can be associated with some types of SEN. In England, the Children’s Commissioner and Ofsted have found evidence of informal exclusions such as children being out on part-time timetables or being sent home without a formal record of being excluded. Informal exclusions have also been highlighted by NICCY. We discussed the issue with the Department and it told us it does not capture data in relation to informal exclusions. It explained that as this practice is not provided for in education legislation any details in relation to it would be anecdotal. It is however undertaking a review of the current policy on suspension and expulsion arrangements in Northern Ireland schools.

2.14 Developing staff expertise is a continual process and, as we previously highlighted in our 2017 report, regular training in SEN identification and provision is important for all staff in schools. Since our last report the Department and the EA have invested in training and development opportunities for schools. Going forward it is essential that the capacity within schools continues to be developed and monitored to ensure that the training available is effective in equipping teachers with the appropriate skills to support all children and improve outcomes.

The needs of the majority of children with SEN are expected to be met at the school-based stages of the Code of Practice

2.15 As outlined in our 2017 report, schools are expected to make reasonable adjustments and provide appropriate support for pupils with SEN. The first three stages of the Code of Practice are based in the school (see Figure 1) and the support provided may include special help within the normal classroom setting at stage 1: an Individual Education Plan drawn up by the SENCO and teacher(s) for stage 2 and beyond; and a range of pupil support services provided by the EA to meet the needs of children and young people mainly at stage 3. These services include language and communication, autism, visual impairment, hearing impairment, specific literacy difficulties, behaviour support, education outside school, early years and support for children with generalised learning difficulties. This stage 3 support occurs at three levels: pupil interventions, advice and support to schools, and training in relation to strategies that are specific to particular types of SEN. The EA told us that these pupil support services are complementary to the work of the school and access to the services is informed by an Educational Psychology Assessment in the majority of cases.

2.16 As we previously reported, following the establishment of a single Educational Psychology Service, a common model for the allocation of psychology services is being used to deliver services to primary and post-primary schools. This includes calculating the time allocation to each school on a regionally-based formula which takes into account the size of the school, educational attainment and a social index of need. The EA told us that the formula used to allocate school psychology hours is based on the anticipated Educational Psychologists’ hours available across the region, factored against an index of need for each school. The EA records and monitors the time provided to each school. The Education Psychology Service issues an annual report to schools, noting how each school is using its allocated time. In 2017 we welcomed the drive for regional consistency and noted the EA would need to ensure that it monitors and reviews the impact of this common model for the time allocation of Educational Psychology Service. To date, the EA has not reviewed the model but told us it plans to do so during 2020.

2.17 The Educational Psychology Service formally consults with schools regarding pupils being considered for an assessment at stage 3, giving the school an opportunity to explore appropriate school based solutions before completing a stage 3 referral. The EA told us that Educational Psychologists help schools identify and prioritise their stage 3 assessment needs. The referrals will only be processed following discussion with the Educational Psychologists and where the school has the necessary number of Educational Psychology Service hours available to progress. This approach is intended to ensure that the number of stage 3 referrals remains steady and within the resource limitations of the EA (see Figure 7). The EA does not hold a waiting list of all the children the schools would like to refer to its pupil support service; this is recorded on the school’s SEN register.

Figure 7: The number of referrals to the Educational Psychology Service is determined by co-ordinated discussion with schools based on their hours available

|

2015-16 |

2016-17 |

2017-18 |

2018-19 |

2019-20 |

|

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

Total pupils referred |

4,461 |

4,197 |

4,434 |

4,183 |

3,421 |

Source: NIAO based on EA documentation.

2.18 At December 2019, the EA employed 106 full time equivalent (136 in 2016) Educational Psychologists and 22 full time equivalent (8.5 in 2016) Psychology Assistants. Despite the reduction in staff, the EA told us that the average waiting time for an Educational Psychologist stage 3 assessment meeting has reduced by 16 per cent over time, from 57 days in 2015-16 to 41 days in 2018-19, against a Departmental target of six months. As the number of referrals to the Educational Psychology Service is determined following discussion with schools and based on the time allocation hours available, the EA can progress each referral quickly. The Department told us that the six month target has been in use for many years and they will review it in consultation with the EA.

2.19 The EA told us there are approximately 13,000 children with SEN receiving EA support services at stage 3. In addition, 1,981 children were supported by the SEN Early Years Inclusion Service during 2019-20. As part of this review we sought details on how many children are waiting to access stage 3 services and how long it takes for them to access the necessary support following their assessment by the Educational Psychologist. The EA advised that each of the services has a different way to quantify service capacity and average response time. EA figures show that the waiting list for some of these services can be very long and NICCY recently reported that there is a “bottle neck” in accessing the stage 3 services, with demand far exceeding supply. The NICCY report also highlighted concerns that the support provided at stage 3 does not last long enough to yield positive lasting results. We are therefore concerned that the length of time spent waiting to access the stage 3 support may in some cases be longer than the period of time for which the support will then be provided.

2.20 A review of pupil support services has commenced (see paragraph 14). This involves reviewing the service delivery frameworks across a range of pupil support services including Psychology, Autism Advisory and Intervention, Sensory Support, Literacy, Language and Communication, Early Years SEN, SEN Inclusion and Behaviour Support. The Department and the EA have recognised that the current delivery models are disparate and that there is a need to simplify access arrangements to services; enhance the visibility of services; and enable access to earlier interventions that have a robust evidence base in terms of effectiveness and pupil outcomes.

Delays in the Statutory Assessment process persist

2.21 In some cases, the needs of children with SEN cannot be met at the school-based stages of the Code of Practice and the EA will have to carry out a Statutory Assessment of need. This is a detailed multi-disciplinary assessment which aims to find out exactly what a child’s needs are and what provision is required. The EA must seek professional advice from the Educational Psychology Service, educational advice, medical and social services advice, as well as parental submissions, together with any other advice which may be considered desirable. All requests for advice specify a date by which it must be submitted.

2.22 When considering a request for Statutory Assessment the EA considers factors such as the size of the school and the relevant budget allocations for SEN which may impact on the range of adjustments and measures that a school can make. The Statutory Assessment will not be conducted without appropriate evidence that the school has made every effort to meet a pupil’s SEN at the school based stages.

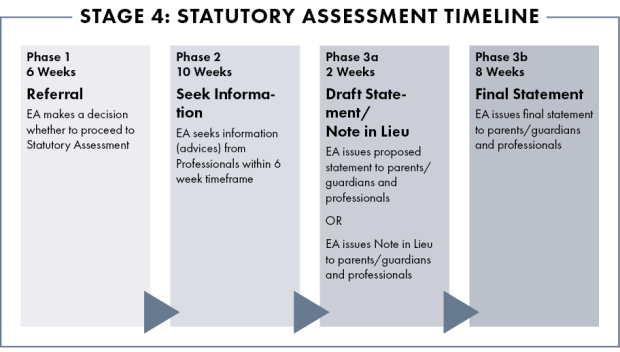

2.23 Under legislation, the length of time taken for the EA to issue a proposed statement must be no more than 18 weeks from the date of receipt of the parent’s or carer’s request for a Statutory Assessment or the EA’s decision to perform an Assessment, whichever is appropriate. The EA then has a further eight weeks to issue a final statement – 26 weeks in total (see Figure 8).

Figure 8: Current outline of Statutory Assessment timeline

Source: the Education Authority.

2.24 The current legislation states that the EA must comply with the statutory timeframe of 10 weeks for Phase 2 unless it is impractical to do so for the following reasons (known as “valid exceptions”):

i. In exceptional cases after receiving the advice it is necessary for the EA to seek further advice.

ii. The child’s parent indicates that he/she wishes to provide advice to the EA after the expiry of 6 weeks and the EA has agreed to consider such advice.

iii. The EA has requested advice from a school during a period when the school is closed for a continuous period of not less than 4 weeks.

iv. The EA has requested advice from the Health Trusts and the Trust has not responded within 6 weeks.

v. Exceptional personal circumstances affect the child or his/her parent during the 10 week period.

vi. The child or his parent is absent from Northern Ireland for a continuous period of not less than 4 weeks during the 10 week period.

vii. The child fails to keep an appointment for an examination or test during the 10 week period.

2.25 In 2017 we reported that despite the time limits assigned to the Statutory Assessment process, in 2015-16 79 per cent of new statements were issued outside the statutory 26 week limit. According to the EA, the majority of cases were valid exceptions, primarily relating to delays in advice from a Health Trust, however a breakdown of the reasons for the delays could not be provided. We recommended that the EA must record and monitor the reasons for all delays in issuing statements in order to take effective action to reduce waiting times (Recommendation 3). We also recommended that the Department should continue to work to improve the waiting time for Statutory Assessments and this should include co-ordinating with the Department of Health to agree on an improved achievable timescale for receiving advice (Recommendation 4).

2.26 Following our report the EA conducted an analysis of the delays, identifying factors internal to the EA including: internal advice sharing was still paper based in some areas; different interpretations of valid exceptions; information management challenges; and work prioritisation. Factors identified as being external to the EA include: requests for Statutory Assessments from schools peaking during end of June and early July which impact on valid exceptions; pace of response from the Health Trusts; and staff sickness absence.

2.27 We found that the EA have formed collaborative relationships with the Health Trusts and the Public Health Agency (PHA) to develop strategies and processes in an effort to reduce the length of time for the completion and return to the EA of the Medical Advice for the children undergoing statementing. These include the establishment of a triage system in partnership with the Health Trusts, to assist with the prioritisation of requests for Medical Advice. The Department told us that in order to further reduce timeframes and unnecessary delays caused by the manual exchange and inputting of information, the EA and Health Trusts are exploring potential solutions for sharing information electronically. Since April 2020, a secure eMail system has been used to exchange information relating to the Statutory Assessment process as an interim solution.

2.28 A SEN co-ordinator and data analysts were appointed to each of the five Health Trusts in 2019. The purpose of the SEN co-ordinators is to streamline processes and improve timescales for the return of Medical Advice to the EA. Data analysts will capture the volume of cases received, record the time of year, and identify pressure points and trends. The EA told us that early indications are that this work is already leading to improvement and further improvements are expected.

In 2019-20, there were delays in issuing 85 per cent of Statutory Assessments

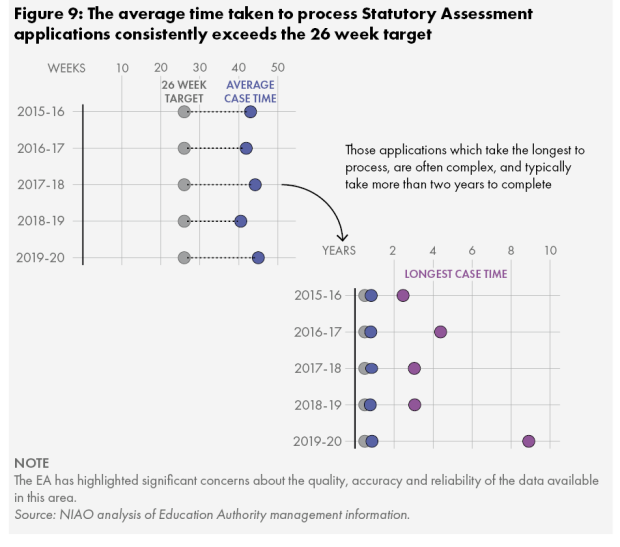

2.29 We were disappointed to find that 85 per cent of Statutory Assessments were issued outside the 26 week statutory timeframe in 2019-20 and as such performance has deteriorated since our last report. The EA provided a breakdown of the reasons for the delays and according to its data the majority are due to Health Trust or Social Service delay.

2.30 However, during 2019, the EA analysed a sample of cases which had exceeded the 26 week timeframe and found that some of the longest delays appeared to be a result of EA delay as opposed to delays in Medical Advice. The “valid exception” was applied as a result of initial delay in receiving Medical Advice, however, once that advice was received the case was not proactively progressed by the EA. The EA told us that when there is more than one reason for delay it is not always recorded on the system and there are different interpretations amongst EA staff in relation to “valid exceptions”, and when they are applicable. Consequently, there is an issue with the reliability of the data. We understand that the EA intends to review the term “valid exception” and develop appropriate guidance to ensure consistency going forward.

2.31 This impact review found the average time for processing Statutory Assessments (see Figure 9 and Appendix 5) has increased from 43 weeks in 2015-16 to 45 weeks in 2019-20. We note that in 2019-20 the longest time elapsed for a Statutory Assessment was 463 weeks, compared to the 26 weeks statutory timeframe. The EA has highlighted significant concerns about the quality, accuracy and reliability of the data available in this area. The EA told us that a service improvement plan has been put in place and it will address the need to improve data quality as a priority.

2.32 The EA told us that in November 2019, 107 children were waiting for more than 80 weeks for their Statutory Assessment to be completed. By early June 2020, this had reduced to 18 children, a reduction of 83 per cent. During the same period the number of children waiting over 60 weeks reduced from 265 to 169 (a 36 per cent reduction) and those over 40 weeks reduced from 540 to 362 (a 33 per cent reduction). The progress being made by the EA is encouraging, however, the impact that such delays have on families and a child’s learning cannot be overestimated.

2.33 Proactive management and monitoring of the cases is essential to prevent any unnecessary delays, however we found a lack of routine management information and monitoring of performance against the 26 week Statutory Assessment timeframe within the EA. This was also identified by the EA during the internal audit of practice (see Paragraph 15) and it has recognised the need for greater use of standardised management information reports to enable more effective monitoring.

The Education Authority is not accurately or consistently recording the Statutory Assessment start dates used to generate reports on compliance with the statutory 26 week timeframe

2.34 The start date for the 26 weeks should be the date the EA receives a referral for a Statutory Assessment. In the cases we looked at we did not find a consistent approach to recording the start date. For example, in one case the date of the decision to give the parents or carers notice of consideration of a Statutory Assessment of SEN was recorded as the start date, instead of the date the referral was received. This effectively amended the start date on the system by 8 weeks. In another case the date the regional Statutory Assessment Panel reviewed the file and decided to proceed to Statutory Assessment was used as the start date, removing 18 weeks from the timeframe recorded on the system. Consequently, the data currently held by EA with regards to performance against the 26 week timeframe is not accurate. We are aware that the EA has also identified anomalies in the start date in a number of cases as part of the internal audit of practice (see Paragraph 15).

The number of appeals and complaints is rising

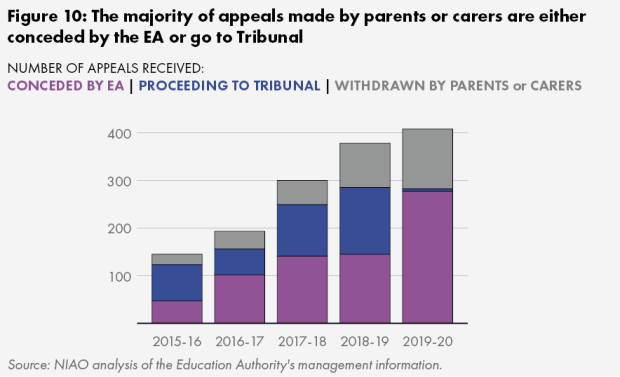

2.35 The number of appeals against the EA decisions in relation to SEN has almost trebled, from 145 appeals in 2015-16 to 408 in 2019-20. The majority of the appeals received are against the EA’s refusal to assess or reassess a child’s SEN. We also found that the number of complaints received by the EA in relation to SEN and the Statutory Assessment process more than doubled between 2017-18 (41 complaints) and 2019-20 (83 complaints).

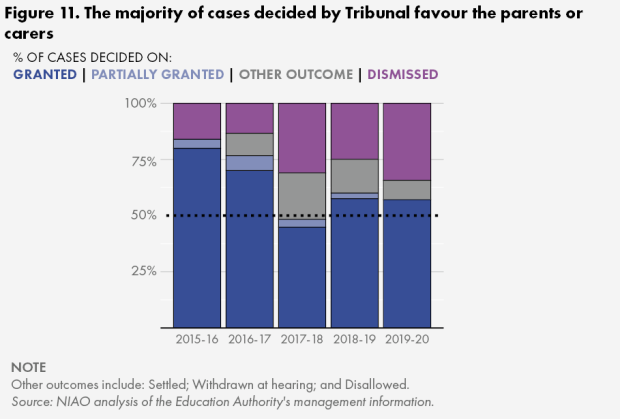

2.36 As shown in Figure 10, whilst some parents or carers will withdraw their appeals, the majority of cases either proceed to Tribunal or are conceded by the EA prior to the Tribunal.

2.37 As shown in Figure 11 and Appendix 5, in the majority of cases, when an appeal goes to Tribunal the decision is in favour of the parents or carers.

2.38 The EA has a Dispute Avoidance and Resolution Service (DARS) providing an informal means of avoiding and resolving parents’ and carers’ disagreements with schools or the EA, relating to a child with SEN. DARS provides an independent, confidential and informal forum to address disagreements. It is to be used for issues that do not generate an appeal right. DARS may facilitate a possible resolution but they do not have the authority to impose the outcomes. The number of cases taken to DARS in recent years has increased by almost 50 per cent, from 164 during 2014-15 to 245 in 2018-19. In September 2019, the EA put in place a contract with Global Mediation for a new DARS, independent of the EA. Global Mediation provide EA with feedback on the uptake of the service so future monitoring will be possible.

2.39 The 2016 SEND Act will require the EA to provide an independent mediation service that will be available to anyone intending to appeal against a decision made by the EA, which gives rise to the right of appeal to a Tribunal. EA’s contract with Global Mediation, for the provision of DARS, also includes provision for a mediation service. The mediation section in the 2016 SEND Act has to be commenced before Global Mediation can start to provide this service. Whilst this may reduce the need for parents or carers to progress to the Appeals Tribunal it will not solve the underlying issues which are resulting in complaints and appeals.

2.40 Decisions by the EA in relation to SEN should be robust and able to withstand challenge. We are concerned about the increasing number of appeals against EA decisions on SEN statements. In our opinion, the number of cases conceded, and the number which are found in favour of the parents or carers when they do proceed to Tribunal, raises questions about whether the processes and procedures followed by the EA in relation to SEN are fit for purpose. There is a clear need for an urgent review and overhaul of the SEN processes in place within the EA.

Part Three: The cost of providing for children with SEN

The EA currently spends in the region of £311 million on children with SEN

3.1 Whilst children without a statement can access a range of pupil support services which are funded by the EA (see Paragraph 2.15), the costs associated with providing support for children with SEN without a statement are primarily funded from school budgets. Once a child has a statement of SEN, the special education provision is centrally funded by the EA.

3.2 Spend by the EA on SEN continues to increase and is currently in the region of £311 million (see Figure 12). Funding is allocated to:

- special schools - staffing and other costs are met centrally by the EA;

- support for children with a statement attending mainstream schools – this includes the cost of adult assistance and also includes the costs relating to learning support centres attached to mainstream schools;

- pupil support services – this refers to the range of services available to schools to support a pupil with SEN (at stages 3, 4 & 5 of the Code of Practice) (see Paragraph 2.15); and

- transport costs.

3.3 In 2017 we reported that total expenditure on SEN could not be readily quantified, there were inconsistencies between the figures held by the Department and the EA and we were unable to get a complete breakdown of expenditure, with only spend on classroom assistants being separately identified. We recommended that the EA must ensure that SEN expenditure was reported consistently and that EA expenditure on all types of support for children with SEN could be easily identified and monitored, otherwise it cannot be controlled (Recommendation 5).

3.4 The financial information available at the time of our previous report was taken from five separate systems operated by the legacy Education and Library Boards. In December 2016 the EA implemented a single financial system and sought to map out consistent financial reporting requirements. We found that the EA is now able to provide a breakdown in relation to SEN spend (see Figures 13 and 15).

In 2019-20, £95 million was spent on adult assistance

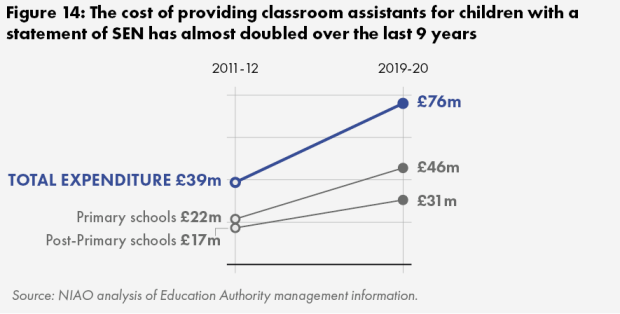

3.5 Spend on providing for children with a statement of SEN in mainstream schools continues to rise and, as shown in Figure 13, the vast majority continues to be spent on adult assistance. This includes general, supervisory and classroom assistants. Of the £95 million spent on adult assistance in 2019-20, £76 million was spent on classroom assistants. The cost of classroom assistants has almost doubled since 2011-12 (see Figure 14).

In 2019-20, £24 million was spent on SEN related pupil support services

3.6 The EA provided the costs associated with the provision of the SEN related pupil support services which are also rising year on year (see Figure 15). We have not included the costs associated with Behaviour Support Services. The Department told us that the costs associated with this service are not wholly attributable to SEN and there is no basis of apportionment at this time to identify the SEN and non-SEN elements of the associated spend.

Figure 15: The EA is now able to provide a breakdown of the SEN related pupil support costs

|

Pupil support services |

2016-17 £k |

2017-18 £k |

2018-19 £k |

2019-20 £k |

|---|---|---|---|---|

|

Educational Psychology Service |

10,040 |

9,814 |

9,441 |

9,849 |

|

Autism Intervention |

2,101 |

2,017 |

2,909 |

3,154 |

|

Sensory Impaired Services |

1,595 |

1,640 |

1,963 |

1,972 |

|

Peripatetic Service |

4,408 |

4,210 |

– |

67 |

|

Literacy Service |

2,741 |

2,712 |

6,120 |

6,722 |

|

SEN Inclusion Service |

– |

– |

– |

825 |

|

Early Years SEN Inclusion |

– |

– |

– |

1,392 |

|

Other SEN support services |

– |

764 |

3,209 |

136 |

|

Total |

20,885 |

21,157 |

23,642 |

24,117 |

NOTE

Staff previously employed in Peripatetic Service are now mostly employed in the Literacy Service and Sensory Impaired Service.

Source: NIAO based on the Education Authority figures.

Work is ongoing to capture the full cost of providing for children with SEN in mainstream schools

3.7 Since our last report, the EA has made efforts to capture school delegated expenditure on SEN to build up a more complete picture of the cost of providing for children with SEN. As part of the 2019-20 Financial Planning process the EA issued a template to all schools designed to capture the delegated planned SEN expenditure, including the number of hours spent teaching, non-teaching support and other non-staffing costs, for example equipment, books, practise material and other resources. Approximately half of schools responded and half of those provided financial information. The EA told us that it will further refine this process and continue to engage with schools to improve the response rate.

3.8 EA expenditure on most types of support for children with SEN can now be identified and this will enable appropriate monitoring and reporting. However, the SEN related costs for Behaviour Support Services cannot yet be separately identified.

A statement may be considered as a gateway to resources and funding

3.9 In 2017 we highlighted that a statement of SEN may be considered as a gateway to resources and funding as the needs of children without a statement have to be primarily met from within the school budget, in addition to the funded pupil support services provided by the EA from stage 3 (see Paragraph 2.15). At that time, the EA considered there was a prevailing view that resources and provision for children with SEN could only be accessed through the Statutory Assessment process and in 2015, it told the Assembly’s Education Committee that “a key change that we need to make and a key message that we need to convey... is that support can be available and effective interventions can take place without a statement.”

3.10 We consider that all children with SEN, with or without a statement, need appropriate support to enable their needs to be met effectively. Therefore, we recommended that the Department and the EA should review the current funding arrangements to ensure that available resources were used effectively to meet the needs of all children with SEN, with or without a statement (Recommendation 6).

3.11 The Department conducted a benchmarking exercise against the funding for SEN in Education Authorities in England and an overview of SEN funding within other jurisdictions. It found that on a per pupil basis, the level of funding per child with SEN in Northern Ireland is less than in England. As part of the Department’s Education Transformation Programme, a project is underway to review the Common Funding Formula (CFF). The CFF project has considered a SEN funding options paper, which includes consideration of directing additional resources to schools, in particular to address the resourcing impact of the additional responsibilities which will be placed on schools when the new SEN Framework is introduced. It is our understanding that additional funding is required to fund the Department’s preferred option. No decisions have been made at the time of our impact review.

3.12 Whilst it is evident that work has been ongoing within the Department to consider the funding arrangements, we note that the proposals are linked to bids for additional funding. It is important to note that our recommendation was based on using the available resources effectively and it should not be considered to be dependent on additional funding. In our opinion, the current funding of SEN services is not financially sustainable. There is a need for a fundamental review to consider the effectiveness of the funding allocated to all stages of the SEN process to ensure the needs of children with or without a statement are met.

This requires an evidence base as to which types of support have the best outcomes for children to ensure resources are used to best effect. It should also include assessing the potential impact of directing more resources to support children without a statement, in an effort to maximise the effectiveness of early intervention measures, which might reduce the need for statementing.

Part Four: Monitoring and evaluation of the impact of SEN provision

4.1 In 2017, we found no evidence that the effectiveness or quality of support provided for children with SEN was monitored at a strategic level by the Department or the EA. In the absence of any evaluation of the support provided, we concluded that it was difficult to see how the Department or the EA could ensure they achieved the best outcomes for children with SEN, or demonstrate value for money.

The ETI can play a major role in monitoring and evaluating SEN provision but has been hampered by the teachers’ industrial action short of strike

4.2 In 2017 we reported that the ETI employed a small number of specialist inspectors, including one with a SENCO background, who worked mainly in special schools. In mainstream schools, the provision for children with SEN was evaluated as an integral part of the inspection process. At that time, the ETI told us that while it would be ideal to deploy a specialist in all inspection teams in mainstream schools, due to the number of inspections carried out on an annual basis and a reducing staff resource this was not always possible. When it was not possible to deploy a specialist inspector, the SEN provision was evaluated jointly by the members of an inspection team. In addition, and where appropriate, inspection findings were quality assured by the specialist SEN team.

4.3 The purpose of inspection is to promote the highest possible standard of learning, teaching, training and achievement throughout the Education sector. We recommended that the Department gave further consideration to the level of expertise within each inspection team to ensure that SEN provision was evaluated in mainstream schools by a specialist, particularly where there was a high proportion of children with SEN (Recommendation 7).

4.4 Since our last report the ETI has conducted internal skills audits and identified a number of staff with SEN skills or an interest in the area. An Associate Assessor recruitment exercise was conducted in June 2018, attracting an additional three staff with SEN skills. The ETI had intended to conduct another Associate Assessor recruitment exercise during 2019 but decided that because of the reduced ability to inspect schools due to the teachers’ industrial action short of strike it was not necessary.

4.5 The ETI’s Schedule of Inspection is giving greater cognisance to the level of SEN needs in a school when deploying the inspectors. The ETI aims to deploy a specialist SEN inspector to schools with the highest numbers of pupils with SEN. Between 2017 and 2019 specialist SEN inspectors were involved in, or led in, 172 inspections across mainstream and special schools. In addition to this, the ETI is implementing a new management information system to assist with inspection planning, monitoring the SEN numbers and the number of SEN specialists within an inspection team. The new management information system went live in June 2020 with a phased roll out planned across the ETI during 2020-21.

4.6 The ETI has engaged in a Professional Development Programme for all staff to further equip them for the increasing numbers of pupils with SEN, including workshops, courses, and information days. Where possible the ETI has deployed inspectors to special school inspections to increase their understanding of the strategies used in special schools to address the increasing challenges faced by teachers in mainstream schools.

4.7 We welcome the work which has been completed to date and the drive to ensure that inspectors with SEN experience are involved in inspections in schools with high numbers of children with SEN. However, we are conscious that the ETI was unable to complete detailed inspections in many schools due to teachers’ industrial action short of strike. Until the ETI recommences its full inspection regime it is difficult to determine if there will be appropriate levels of expertise available for each inspection team.

4.8 Our 2017 report found that the ETI last evaluated the overall provision for SEN in primary and post-primary schools in 2007-08 and 2006 respectively. While a number of strengths were identified, one area for improvement was evaluating the progress and achievements of children with SEN. We recommended that the Department should commission the ETI to carry out an up-to-date evaluation of SEN provision in mainstream schools which could play a key part in highlighting areas to be addressed in the development of SEN strategy and future training programmes. A particular focus in primary schools should be the use of, and effectiveness of, early intervention strategies (Recommendation 8).

4.9 In response to our recommendation, the Department commissioned the ETI to carry out an evaluation of the impact of SEN provision in mainstream schools on pupil outcomes, with a particular focus on effective early intervention strategies and support. A full ETI evaluation of the quality of the provision for SEN was inhibited by action short of strike by four of the teaching unions. This action included non co-operation with the ETI. As a consequence, twenty primary schools and ten post-primary schools, which had been evaluated previously by the ETI as having highly effective provision for pupils with SEN, were selected for an evaluation of the SEN provision. There was a particular focus in primary schools on the use of, and effectiveness of, early intervention strategies.

4.10 In May 2019 the ETI published its SEN evaluation report, entitled ‘Report of a survey of Special Educational Needs in mainstream schools’ (see Paragraph 2.5). The report, issued to every school in Northern Ireland, reported on effective practice, including case studies, and a summary of key findings arising from the evaluation (see Appendix 3). Complementary video sessions involving some of the schools surveyed were uploaded to the Department’s website. The ETI developed eight recommendations, including continuing professional SEN development for teachers and streamlining and simplifying access to additional support when needed. However, the decision was made not to include the recommendations within the report. The Department told us that as some of the recommendations required additional funding it did not want to create unrealistic expectations and decided they would be taken forward separately with the EA.

4.11 It is disappointing that a full evaluation of SEN provision in mainstream schools has not been completed due to action short of strike. Whilst we welcome the sharing of good practice we are concerned that practice in these schools, with a highly effective provision for pupils with SEN, is not representative of the situation in many other schools. There remains a need to evaluate the provision for children with SEN in primary and post-primary schools, identifying strengths and weaknesses in the current provision across Northern Ireland.

More still needs to be done to monitor and evaluate progress

4.12 Our 2017 report highlighted the importance of regularly monitoring children’s progress to ensure they are achieving their full potential. However, we found there was a lack of focus on outcomes. Neither the Department nor the EA collated details on the number of children with SEN who progress well with the additional support provided and subsequently revert to an earlier stage of the Code of Practice, or no longer need additional help.

4.13 We found no evidence that the effectiveness or quality of the support provided for children with SEN was monitored or evaluated at a strategic level by the Department or the EA. We concluded that in the absence of any evaluation of the support provided, it was difficult to see how the Department or the EA could ensure they achieved the best outcomes for children with SEN, or demonstrate value for money. We recommended that the Department and the EA must assess the quality of SEN support provided in mainstream schools by formally evaluating it in terms of the progress made by children. This would allow resources to be focused on types of support which maximise progress and improve outcomes (Recommendation 9).

4.14 We found that work is ongoing across the EA to identify outcomes for children and young people, as well as data systems which will support collation, analysis, reporting and use of outcomes information. During March 2018 the EA appointed a Lead Officer with responsibility for progressing work associated with monitoring and maximising pupil outcomes. In May 2018 the EA established the Outcomes Based Accountability Group to consider practices to standardise data collection, collation and reporting across the Children and Young People Services (CYPS) and develop a CYPS Management Information System. A CYPS Outcomes Based Accountability Framework is at final draft stage and the EA intends to apply it during 2020-21. The EA is continuing to develop the performance indicators and measures which will be included in the framework and the reporting output will be built up over time.

4.15 During 2020, work commenced with six schools in software testing and development of Personal Learning Plans (PLPs) for pupils. Due to the impact of COVID-19 this work has been suspended and it is intended it will resume in autumn 2020. The development of these digital PLPs will increase the speed at which plans can be developed, provide consistency around format, and allow the school to set targets and monitor pupil outcomes more effectively. It is intended that the PLPs will provide important base information on which the EA and the Department can assess the effectiveness of SEN provision.

4.16 As noted in Paragraph 14 a review of pupil support services is underway. Intended outcomes include:

- an agreed regional model of provision to support SEN pupils that: is effective; efficient; sustainable; transparent; and equitable;

- better outcomes for children and young people with additional needs;

- earlier and more effective intervention for SEN pupils; and

- reduction in resources spent on statementing and more invested in pupil support services.

4.17 Paragraphs 2.5 – 2.6 provide details of the evaluation work carried out by the ETI since our 2017 report. We understand that this will include a second phase to this work which will include more in-depth research, focusing on the impact of support provided to children with SEN and the outcomes. This second phase could not be commenced during the action short of strike by teachers, which ceased on 28 April 2020. The second phase will be carried out following ETI’s return to inspection activity post COVID-19.

4.18 Whilst work has commenced to address this recommendation it is still at an early stage and limited progress has been made. The effectiveness of the various types of support provided to children has not yet been evaluated. As such there is no evidence that the support is adequate or positively impacts on outcomes for children. Nor is there any evidence base as to which types of support are the most appropriate or effective. In the absence of such evaluations there are no assurances that resources are being used on the types of support which could maximise progress.

Statements of SEN are reviewed each year but there is no robust data held by the EA on the outcomes from that process

4.19 As reported in 2017, the EA is required to review over 17,000 statements of SEN each year. The annual review aims to: assess progress with a focus on the outcome of the targets identified in the Individual Education Plan; review the special provision made for the child; consider the appropriateness of maintaining, amending or ceasing the statement; and, where appropriate, set fresh targets for the coming year. Following the annual review meeting, the school principal prepares a report summarising outcomes and setting out any educational targets for the coming year. The EA then reviews the statement. This may result in an amendment to the statement or the statement no longer being maintained.

4.20 At the time of our 2017 report, the EA told us that around 80 per cent of statements remain unchanged following the annual review. We also reported that in 2015-16 only five per cent of the 1,318 statements ceased as a result of sufficient progress being made, so the statement was no longer required. The vast majority ended because the child reached the upper limit of compulsory school age. Research by Queen’s University estimated that the mean annual cost of each review was £350, with an annual cost of almost £6 million. The research also found that the mean annual cost of maintaining a statement was estimated to be £10,000 at key stages 1 and 2 and £7,000 at key stages 3 and 4.

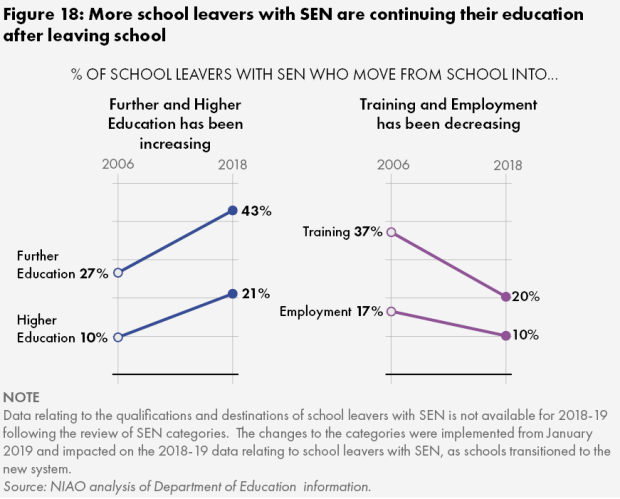

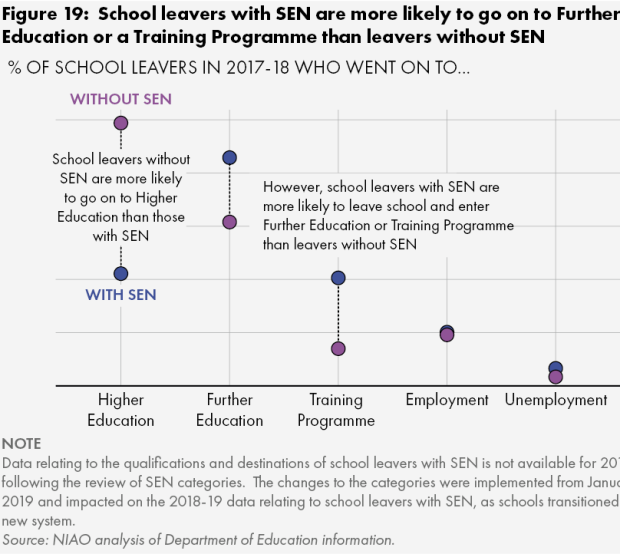

4.21 We sought an update from the EA. It was unable to quantify costs associated with maintaining and reviewing statements, and robust data on statement amendments or the reasons for cessation is not yet available from the EA information system.