Abbreviations

3PD Third Party Development

ALB Arm’s Length Body

BRT Belfast Rapid Transit

CBI Confederation of British Industry

CEF Construction Employers Federation

CoPE Centre of Procurement Expertise

CPD Construction and Procurement Delivery

DAERA Department of Agriculture, Environment and Rural Affairs

DE Department of Education

DfC Department for Communities

DfE Department for the Economy

DfI Department for Infrastructure

DoF Department of Finance

DoH Department of Health

DoJ Department of Justice

DTS Delivery Tracking System

EIB European Investment Bank

EU European Union

FBC Full Business Case

FTC Financial Transaction Capital

GB Great Britain

GMPP Government Major Projects Portfolio

HS2 High Speed Rail Programme

IFA Irish Football Association

IPA Infrastructure and Procurement Authority

IRFU Irish Rugby Football Union

ISNI Investment Strategy for Northern Ireland

NAO National Audit Office

N/A Not applicable

NHS National Health Service

NICS Northern Ireland Civil Service

NIEA Northern Ireland Environmental Agency

NIFRS Northern Ireland Fire and Rescue Service

NIGEAE Northern Ireland Guide to Expenditure Appraisal and Evaluation

NIPS Northern Ireland Prison Service

NISRA Northern Ireland Statistics and Research Agency

N/K Not Known

OBC Outline Business Case

OECD Organisation of Economic Co-operation and Development

PAR Project Assessment Review

PCCC Primary Community Care Centre

PfG Programme for Government

PPP Public Private Partnership

PSNI Police Service for Northern Ireland

RAG Red, Amber and Green

RGH Royal Group of Hospitals

RIBA Royal Institute of British Architects

SIB Strategic Investment Board

SRO Senior Responsible Officer

TEO The Executive Office

UCGAA Ulster Council Gaelic Athletic Association

UK United Kingdom

UU Ulster University

Executive Summary

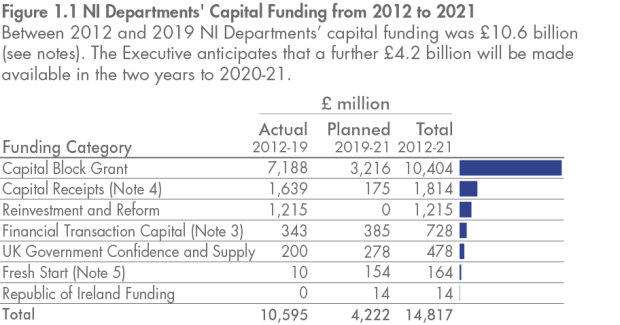

1. Over the eight year period to 31 March 2019, almost £10.6 billion was spent on Northern Ireland public infrastructure. Current estimates indicate that by 31 March 2021, a total of over £14.8 billion will have been invested in Northern Ireland (over a ten year period). This exceeds the £13.3 billion anticipated in the latest Investment Strategy for Northern Ireland (ISNI 2011-21).

2. The construction industry is the second largest industry in Northern Ireland with over 10,300 businesses (14 per cent of all businesses at December 2018) and an estimated 35,020 employee jobs (4.5 per cent of all employees). Northern Ireland infrastructure construction (including for example, roads, bridges, water/sewage works, power stations, gas storage and pipelines, airports, railways and harbours) is substantial, at around £677 million in the 12 months to December 2018 – just under half of this (£330 million) was attributable to public sector work.

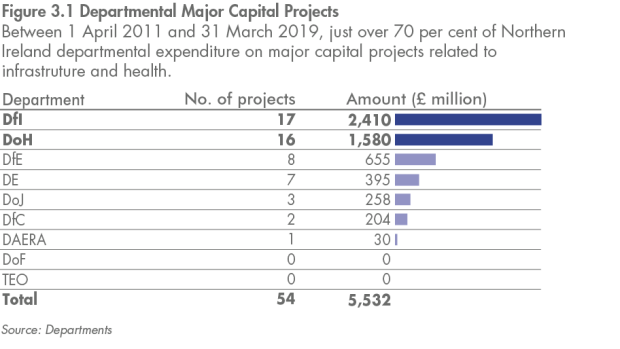

3. In the period from 2011 to 2019, departments managed 54 major capital projects (over £25 million excluding local government and housing association projects) with a total estimated cost of £5.5 billion. The majority of the major capital projects (61 per cent by number and 72 per cent by cost) were managed by two departments - the Department for Infrastructure (DfI) and the Department of Health (DoH).

4. The DfI reported the largest major capital project portfolio, 17 projects (31 per cent of the total) with a combined cost of £2.4 billion (43 per cent of the total). The majority of the DfI projects relate to roads and transportation including, for example, the A5 and A6 road schemes.

5. The DoH reported 16 major capital projects (30 per cent of the total) with a combined estimated cost of £1.6 billion (29 per cent of the total). The majority of DoH major capital projects are managed within the Health and Social Care (HSC) Trusts or within its other Arms Length Bodies (ALBs) and typically involve creating additional, or replacement, facilities, for example, the Mother and Children’s Hospital.

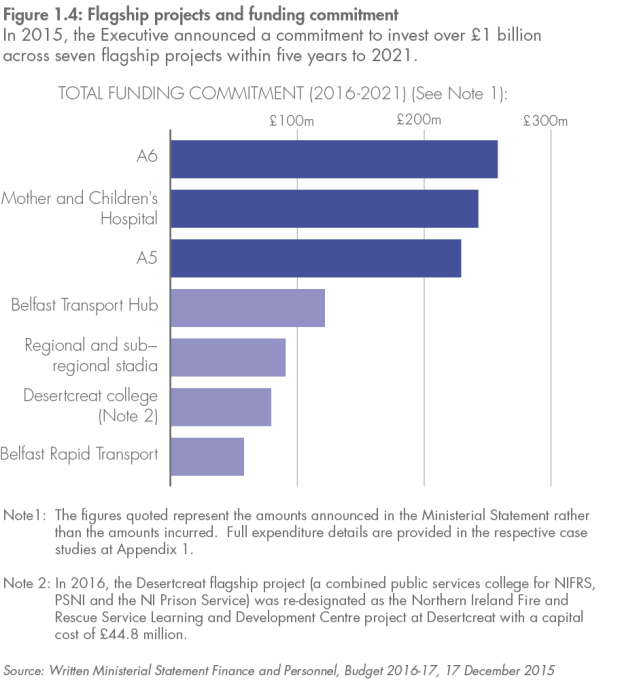

6. In 2015, the Northern Ireland Executive identified seven flagship infrastructure projects as its highest priority projects. Funding for these projects was allocated over a five year period. Total investment for these projects over the period from 2016 -17 to 2021-22, was estimated at just over £1 billion.

7. We conducted a high level review of each of the flagship projects and four additional projects which we know have experienced problems. We found that each of the projects examined suffered time delays and/or cost overruns when compared against original timescales and budgets. Departments told us that typically, time delays and cost overruns occurred as a result of one or more of the following:

- funding constraints;

- legal challenges;

- planning issues;

- limited interest from the construction industry; and

- issues with the quality of construction.

8. Three projects we examined have encountered significant problems: the A5 project, which was brought to the point of construction on schedule in August 2012, is currently expected to be delivered 10 years later than the original planned delivery date as a result of several legal challenges and uncertainty over future funding; the Critical Care Centre which is now expected to be completed (and fully occupied) eight years later than originally planned following various construction problems and; the Ulster University, Greater Belfast Development which needs to attract substantial additional external finance to bridge the current, major funding gap.

9. Lead departments delivering major capital projects will work with a range of bodies including the Procurement Board, the Strategic Investment Board, various divisions within the Department of Finance (DoF) and other Northern Ireland departments.

10. In 2013, a review of the commissioning and delivery of major infrastructure projects in Northern Ireland found that, “despite there being areas of good practice and effective delivery within the commissioning and delivery system and despite the best efforts of able and hard-working staff, the system as a whole is not fit for purpose and works against … best endeavours to deliver”.

11. The review concluded that change was necessary to all parts of the current system and that “the system needs to be overhauled and reformed in order to enhance its efficiency and effectiveness, and to ensure that it delivers better value for money for taxpayers”. The review team considered that there was “a real opportunity ….. for the Executive to build a high performance commissioning and delivery system for procuring the infrastructure which Northern Ireland needs”.

12. The report did not receive universal support and while DoF progressed a number of the actions for which it had responsibility, the proposed reform stalled and, consequently, some of the improvements to the commissioning and delivery of infrastructure are not being realised.

13. In 2013, the Confederation of British Industry (CBI) advised that various changes were required to Northern Ireland arrangements to enhance the ability of the public sector to deliver value for money. These included the need for more intelligence-led commissioning of infrastructure, a change from the process-driven culture, more realistic budgets and prioritisation of turnkey solutions. It recommended that Northern Ireland move towards models in Scotland and the Republic of Ireland by creating a new centralised procurement and delivery agency to develop and deliver infrastructure taking responsibility, initially, for education and health capital building projects; and seek to drive efficiencies in delivery costs. The CBI acknowledged the need to retain the existing DfI CoPEs (Translink, Northern Ireland Water and Roads Service) as individual entities “focusing on the intensive civil engineering works, and other specialisms in which they are already experts”.

14. While recognising efforts to ensure efficiency in major infrastructure procurement in Northern Ireland, in 2016 the Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development (OECD) highlighted the need to clarify the roles and responsibilities of key stakeholders and, as a result, eliminate duplication in administrative functions and institutional frameworks. It concluded that the need to better respond to the procurement needs of government had not been matched by the development of new procurement approaches or the adoption of new solutions. The OECD was critical of developing expertise across numerous departments, which it considered duplicative and costly.

Concluding Commentary

15. This report presents an overview of the Northern Ireland major capital projects portfolio. Appendix 4 provides high level information on the 54 major capital projects commenced by government departments and their ALBs during the period 1 April 2011 to 31 March 2019. It is clear from the information provided by departments, that performance in delivering these complex projects varies and while some projects deliver the intended outcomes to cost and time, many suffer cost overruns and/or significant time delays against original estimates.

16. While accepting that project delivery problems are not unique to Northern Ireland, it is disappointing that, in the 11 high profile projects considered in this report, costs and timescales envisaged at the outset of projects, were not achieved. Even flagship projects, identified as the Northern Ireland Executive’s highest priority and with funding secured over a longer period, have suffered time delays and/or cost overruns. Inevitably, where projects suffer substantial cost overruns, this impacts on the delivery of other projects.

17. Departments told us that significant issues leading to delays are often encountered at the pre-construction stage, particularly in the case of major road projects as a result of funding issues, legal challenges, planning issues or due to limited interest in the project from the construction industry. The identification of flagship projects was an effective way of addressing funding issues for high priority projects by protecting budgets on those projects over a five year period, however performance in delivering against estimated costs and deadlines will only improve when each of the challenges faced by departments is addressed simultaneously.

18. In our view, the existing cumbersome governance and delivery structures within the Northern Ireland public sector are not conducive to maximising the achievement of value for money. Several reports on Northern Ireland public procurement have highlighted the potential for improving performance across Northern Ireland Civil Service (NICS) departments by, for example, creating a new centralised procurement and delivery agency to develop and deliver infrastructure and streamline public sector processes. We do not wish to be prescriptive about future structures, but we consider that there is considerable merit in considering how alternative models, resourced with sufficient, highly skilled staff might improve future infrastructure delivery.

19. Given the importance of major capital projects to the economy of Northern Ireland, this is an area which we will be revisiting. Our future work programme will include in-depth assessments of the extent to which value for money has been achieved in a number of individual projects. Also, in view of the number of projects which have experienced significant delays because of legal challenges and planning issues, we are conducting two separate pieces of work: one identifying the lessons arising from Judicial Reviews and another considering the efficiency and effectiveness of the Northern Ireland planning system.

Conclusions and Recommendations

20. A series of reviews of the roles of the Procurement Board, CPD, SIB and commissioning entities have highlighted that current commissioning and delivery arrangements in Northern Ireland are not fit for purpose and have identified the need to:

- eliminate duplication in administrative functions and institutional frameworks;

- improve project prioritisation;

- reduce bureaucracy by focusing more on ‘within budget’ and ‘on time’ delivery, rather than on process; and

- drive better deals by increasing innovation.

21. We fully endorse these recommendations. While we note the transfer of the relevant part of the Health Estates Investment Group to CPD in 2014, it is disappointing that further progress in transforming commissioning and delivery arrangements in Northern Ireland has not been made.

22. We agree that there is significant merit in considering how alternative models, resourced with sufficient, highly skilled staff could improve future infrastructure delivery by supplementing public sector skills with those available in other sectors and streamlining processes. We recommend that the potential benefits of alternative models are fully explored as a matter of priority.

23. The Northern Ireland public sector faces significant challenges delivering against its major capital projects portfolio. From our high level overview of a number of projects and our focus group, we identified that challenges typically include funding difficulty or uncertainty, challenges through the courts, delays with planning or a lack of appetite and capacity within the local construction industry to take o public sector work.

24. Although in 2015, the Northern Ireland Executive identified a number of flagship projects and prioritised these by providing secured funding over the five year period to 2022, we noted that a number have not proceeded as originally planned. Further, where projects have been completed, in many cases, estimated timescales and costs were exceeded.

25. Part 2 of this report recommends considering the potential benefits of alternative commissioning and delivery models. We acknowledge that it will take time to identify and select the most suitable model for the future. Given that many of the projects we obtained detail on experienced similar problems, we recommend that, in the interim, contracting authorities collaborate and share best practice.

Part One: Introduction and background

This report presents an overview of the Northern Ireland major capital projects portfolio and examines departmental progress in delivering a number of significant projects

1.1 This report presents an overview of the Northern Ireland major capital projects portfolio. For the purposes of this report, we have defined major as over £25 million and have excluded projects relating to local government and housing associations. The report also examines departmental progress in delivering a number of major capital projects and draws out the challenges the public sector faces in managing capital projects.

1.2 Our findings are based on:

- information obtained from government departments and their arm’s length bodies (ALBs) on the capital projects portfolio (Figure 1.5, Figure 3.1, Figure 3.2 and Appendix 4);

- a high level review of each of the flagship projects and an additional four projects which we know have suffered delays, which established timelines, tracked (estimated and actual) costs and sought explanations for project delays and cost overruns. A summary of the progress on, and challenges encountered with, each of the projects is provided at Appendix 1;

- discussions with Strategic Investment Board (SIB) and Construction and Procurement Delivery (CPD) staff;

- a focus group meeting attended by representatives from each of the government departments, CPD and SIB. Each attendee is involved or experienced in some aspect of major capital project delivery, management or oversight. Attendee views are provided throughout this report;

- discussions with representatives from the Construction Employers Federation in Northern Ireland; and

- a review of other relevant literature.

1.3 The main issues covered in this review are:

- the roles and responsibilities in relation to capital projects (Part 2) – setting out and considering the suitability of arrangements in Northern Ireland for commissioning and delivering capital projects; and

- the project management process (Part 3) – examining the progress made on delivery of 11 major capital projects and highlighting reasons for time delays and cost overruns.

Over the period from 2012 to 2021, £14.8 billion capital funding will be available to Government Departments in Northern Ireland

1.4 Capital funding of £10.6 billion was provided to support capital projects in Northern Ireland over the period 2012 to 2019. In the two years to 2020-21, the Northern Ireland Executive (the Executive) anticipates that an additional £4.2 billion will be made available (Figure 1.1). The majority of funding (70 per cent) is made available through the Northern Ireland block grant.

Source: Department of Finance

Notes:

1) This figure includes actual funding received between 2012 and 2019 and estimated funding levels from 2019 to 2021.

2) Figures for the Belfast Region City Deal and Derry and Strabane City Deal have not been included in this figure as the profiling has yet to be confirmed with HM Treasury.

3) Financial Transaction Capital (FTC) is funding allocated to the Executive by the United Kingdom (UK) Government. While the Executive has discretion over FTC allocations to projects, it can only be deployed as a loan to, or equity investment in, a capital project delivered by a private sector entity.

4) Capital receipts for planning years are not yet known. Capital receipts over the period 2012-19 amounted to almost £1.6 billion. These consisted mainly of developers’ contributions in respect of NI Water and Roads; proceeds from the disposal of land and buildings; loan repayments, mainly relating to the NI Housing Executive; and European Union funding, the European Regional Development Fund is the main EU Structural Investment Fund. DoF told us that, over the period 2012-19, capital grants totalling £350 million had been received from the EU.

5) This does not include a re-profile of Fresh Start (Shared Education) Capital which will increase 2019-20 funding by £6.9 million and 2020-21 by £47.5 million. Although the re-profiling has been agreed by HM Treasury, it has not yet been formally included in a HM Treasury fiscal announcement.

The scale of investment in major capital projects in Northern Ireland is significantly less than in Great Britain

1.5 Unsurprisingly, the scale of major capital investment is much larger in Great Britain (GB). The Government Major Projects Portfolio (GMPP) contains details of the most complex and strategically significant GB projects and programmes. Projects included in the GMPP are those which have required HM Treasury approval either because their budget exceeds departmental expenditure limits, or it requires primary legislation, or is innovative or contentious.

1.6 In 2017-18, the GMPP listed 133 projects to be delivered by 16 departments/arm’s length bodies, with a Whole Life Cost of £423 billion (see Figure 1.2). Projects included under Infrastructure and Construction include, for example, the High Speed Rail Programme (HS2) connecting London to Manchester and Leeds, with initial costs estimated at £30 billion; and the Crossrail Programme, a 73 mile rail line crossing London east to west, estimated to cost £15 billion.

Figure 1.2: Whole Life Costs of projects listed in the GMPP

|

Category of Project |

Total Number of Projects |

Estimated Whole Life Cost |

|---|---|---|

|

Transformation and Service Delivery |

41 |

£83 billion |

|

Information and Communications Technology |

29 |

£10 billion |

|

Infrastructure and Construction |

31 |

£196 billion |

|

Military Capability |

32 |

£134 billion |

|

TOTAL |

133 |

£423 billion |

Source: Infrastructure and Projects Authority (IPA)

The construction industry in Northern Ireland is important to the economy

1.7 The construction industry is the second largest industry in Northern Ireland (after agriculture) with over 10,300 businesses (14 per cent of all businesses at December 2018) and an estimated 35,020 employee jobs (4.5 per cent of all employees). It is estimated that the construction industry accounted for 7.2 per cent of the regional Gross Value Added in 2017 (latest available regional data).

1.8 Despite fluctuations, the total volume of construction output in Northern Ireland, has been on an upward trend in recent years. This was largely due to increased output in two of the three construction sub-sectors, housing and ‘other work’, and mainly as a result of increases in private sector output. While infrastructure output (one of three construction sub-sectors) is substantial (£677 million in the 12 months to December 2018) it has declined as a proportion of overall construction output, from 28 per cent in 2013 to 22 per cent in 2018.

1.9 On 2 September 2019, the Construction Employers Federation (CEF) published the latest State of Trade Survey covering the first half of 2019. It reported the opinions of 80 Northern Ireland headquartered construction firms which were, collectively, responsible for turnover of approximately £975 million during 2018-19. These local construction firms consider that:

- 60 per cent of respondents think the local construction market will worsen in the next 12 months, 25 per cent think it will stay the same;

- As a direct result of the Stormont impasse, 60 per cent of firms have put off growth plans;

- Only 35 per cent of respondents said they were operating at full or almost full capacity, compared to 75 per cent in February 2019;

- 30 per cent hope to increase profitability in the year ahead while 25 per cent of firms are in survival mode – up from 20 per cent in February 2019.

1.10 CEF attributed the additional economic uncertainty to Brexit and the reality of over two and a half years since the collapse of the Executive. While CEF acknowledged that the restoration of the Executive cannot, alone, solve this crisis, it recognised that its absence has impacted on the sustainability of the pipeline of work (which provides certainty to the market) and created infrastructure funding challenges which are continuing to hold vital development back.

1.11 CEF reported that, in its view, funding challenges are most prevalent with Northern Ireland Water. It considers that the consistent underfunding of NI Water has led to a “drastic curtailment in much needed wastewater treatment works upgrades right across Northern Ireland and, consequently, a significant slowdown in the number of new homes being started and completed”.

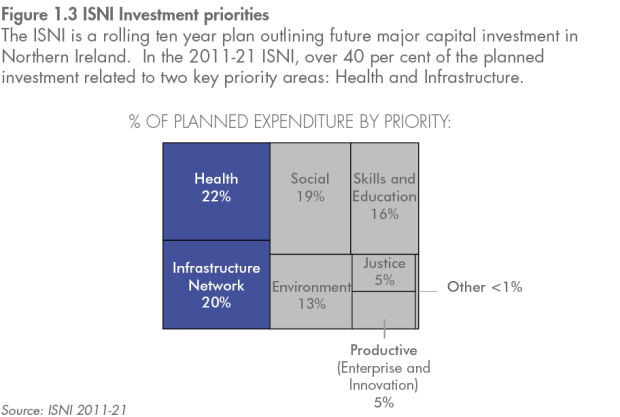

The Executive’s Programme for Government clarifies government priorities and sets the context for the Investment Strategy for Northern Ireland

1.12 The Programme for Government (PfG) 2011-15 (2016 -21 is in draft) sets out the Executive’s priorities and identifies the actions necessary to address them. Priority 1 relates to Growing a Sustainable Economy and Investing in the Future and provides the context for the Executive’s Investment Strategy Northern Ireland (ISNI). The ISNI is a rolling 10 year plan outlining future investment in major capital projects across Northern Ireland.

1.13 The Strategic Investment Board (SIB) prepares the ISNI on behalf of the Executive. The current strategy 2011-21 (2017-27 is in draft) is the second update to the original strategy (produced for 2005 -15) and outlines plans to invest a total of £13.3 billion (Figure 1.3) over the period from 2011-12 to 2020 -21. In the period from 2015 to 2021, the ISNI anticipates that just over £1 billion of this total will be funded by alternative finance (supplementing conventional funding through the NI Block Grant) as follows:

- almost £400 million on roads;

- over £200 million on schools and youth; and

- over £500 million on primary care, hospitals and public safety.

1.14 In addition to setting out the funding allocations for each of the seven key infrastructure areas (pillars), the ISNI details:

- key achievements (over the period 2008 to 2012) against each pillar (summarised at Appendix 2);

- projects underway; and

- planned projects.

In 2015, the Executive announced seven flagship projects as its highest priority projects

1.15 Given their size and complexity, capital projects usually run for several years. The allocation of annual budgets to departments can cause funding uncertainty for capital projects. In order to address this, in 2015 the Executive identified seven infrastructure flagship projects as its highest priority projects. Funding for these projects was allocated over a longer, five year period. Total investment for these projects over the period from 2016 -17 to 2020 -21 was estimated at just over £1 billion (Figure 1.4).

We considered progress on each of the flagship projects (and an additional four projects we knew were encountering problems) and found that almost all have experienced time delays and cost overruns

1.16 We conducted a high level review of each of the flagship projects and four additional projects which we know have experienced problems (Critical Care Centre (at the Royal Group of Hospitals), Primary Community Care Centres (at Lisburn and Newry), Ulster University, Greater Belfast Development and Strule Shared Education Campus). Figure 1.5 provides details on the progress in delivering each of these projects. More detail on individual projects is provided at Appendix 1 and summarised in Part 3 of this report.

Concerns regarding performance in delivering major capital projects across the United Kingdom have been widely reported

Northern Ireland Audit Office Reports

1.17 We have published a number of reports on capital projects. Several of our reports highlighted instances where delivery difficulties have been experienced. Common issues faced by public sector bodies have included the failure to:

- undertake comprehensive preparation work;

- allocate key project governance roles promptly;

- actively manage projects; and

- identify and share learning.

National Audit Office

1.18 The National Audit Office (NAO), in a 2016 briefing to the Public Accounts Committee, stated that the public sector has had a poor track record in delivering projects successfully. While it reported improvements in the way aspects of project delivery were managed in some departments, it highlighted that frequently projects were not delivered on time or within budget and had not achieved their intended outcomes.

1.19 The NAO, in addition to undertaking reviews of major projects and programmes (around 100 since 2010), has produced various aids on project and programme management, including:

- Framework to Review Programmes (13 September 2017) provides a guide for examining projects and programmes, with a series of questions (grouped under four elements) that need to be considered – purpose; value; programme/project set-up; and delivery and variation management; and

- Survival guide to challenging costs in major projects (21 June 2018) highlights factors that can lead to cost growth and seeks to help by providing tips on the early warning signs and suggesting challenges to over-enthusiastic sponsors and project teams.

Infrastructure and Procurement Authority (IPA)

1.20 The IPA is government’s centre of expertise for infrastructure and major projects. It has recently reported that the common causes of failure in major projects are well known, and are similar in the public and private sector and across a wide range of project types. It identified the common causes of failure in major projects as:

- lack of clarity around project objectives;

- lack of alignment amongst stakeholders;

- unclear governance and accountability;

- insufficient resources (human or financial);

- inexperienced project leadership; and

- over-ambitious cost and schedules.

1.21 The IPA considered that well-designed projects address all these issues in the vital project initiation phase, concluding that good project initiation maximises the chance of a successful outcome.

Figure 1.5 Summary of Performance on the flagship and four other major capital projects at 31 March 2019 against Outline and Full Business cases

|

Department |

Case Study (Appendix 1) |

Project |

Estimated Completion Date1 |

Actual/ Latest Estimated Completion Date (N/K= Not Known) |

Actual/ Potential Time Overrun from OBC (Years) (N/K= Not Known) |

Estimated Cost1 £ million |

Final/Latest Estimated Final Costs £ million |

Actual/ Estimated (Under)Overspend From OBC2 (N/K= Not Known) |

Actual Costs Incurred by March 2019 £ million |

||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

OBC |

FBC |

OBC |

FBC |

£ millions |

% |

||||||||

|

DfI |

1. |

A5: Londonderry, Strabane, Omagh, Aughnacloy |

|

2018 |

- |

2028 |

10 |

799.03 |

- |

1,100.0 |

301.0 |

37.7% |

80.3 |

|

2. |

A6: |

Randalstown to Castledawson |

- |

2020 |

2021 |

1 |

- |

184.04 |

189.0 |

5.0 |

2.7% |

119.8 |

|

|

Dungiven to Drumahoe |

- |

2021 |

2022 |

1 |

- |

239.0 |

222.7 |

(16.3) |

(6.8%) |

48.7 |

|||

|

Caw to Drumahoe (project on hold) |

- |

2024 |

N/K |

N/K |

- |

171.0 |

171.0 |

0 |

0 |

5.9 |

|||

|

3. |

Belfast Rapid Transit |

|

2017-18 |

2018-19 |

2018-19 |

1 |

98.5 |

87.9 |

94.4 |

(4.1) |

(4.2%) |

93.6 |

|

|

4. |

Belfast Transport Hub |

|

2023 |

2025 |

2025 |

2 |

208.9 |

227.2 |

227.2 |

18.3 |

8.8% |

20.3 |

|

|

DoH |

5. |

Mother and Children’s Hospital |

Regional Childrens’ Hospital |

2020 |

- |

2025 |

5 |

223.0 |

- |

353.9 |

130.9 |

58.7% |

39.4 |

|

Maternity Hospital |

2015 |

2021 |

2021 |

6 |

57.2 |

72.8 |

73.9 |

16.7 |

29.2% |

29.3 |

|||

|

6. |

Critical Care Centre |

2012 |

- |

2020 |

8 |

95.0 |

- |

151.7 |

56.7 |

59.7% |

151.3 |

||

|

7. |

Primary Community Care Centres: |

Lisburn PCCC |

2016 |

- |

2021 |

5 |

3PD unitary charges expected to be in line with estimates. |

||||||

|

Newry PCCC |

2016 |

- |

N/K |

2 year build not started 3 years after expected completion date. |

3PD unitary charges expected to be in line with estimates. |

||||||||

|

8. |

NIFRS Learning and Development Centre, Desertcreat5 |

Phase 1 |

2018 |

2019 |

2019 |

1 |

4.2 |

4.8 |

4.8 |

0.6 |

14.3% |

4.7 |

|

|

Phase 2 |

2020 |

2023 |

2023 |

3 |

40.6 |

41.6 |

41.6 |

1.0 |

2.5% |

0 |

|||

|

DfC |

9. |

Regional Stadia Programme and Sub-Regional Stadia Programme for Soccer: |

Windsor Park |

2015 |

- |

2016 |

1 |

35.0 |

- |

35.0 |

0.0 |

0% |

35.0 |

|

Kingspan |

2015 |

- |

2015 |

0 |

16.5 |

- |

16.5 |

0.0 |

0% |

16.5 |

|||

|

Casement Park |

2016 |

- |

N/K6 |

Not started 3 years after expected completion date. |

77.5 |

- |

110.0 |

32.5 |

41.9% |

10.3 |

|||

|

Sub-Regional Stadia Programme for Soccer |

No OBC |

- |

N/K7 |

Not started 1 year after expected completion date. |

36.2 |

- |

36.2 |

N/K |

N/K |

0 |

|||

|

DfE |

10. |

UU, Greater Belfast Development |

|

2018 |

- |

2021 |

3 |

254.0 |

- |

363.98 |

109.9 |

43.3%9 |

151.3 |

|

DE |

11. |

Strule Shared Education Campus |

2020 |

- |

2024 |

4 |

168.910 |

- |

213.7 |

44.8 |

26.5% |

37.8 |

Source: Departments have verified all date and cost information.

Note 1: Estimated completion dates and estimated costs were obtained from project Outline Business Cases and, where available, Full Business Cases.

Note 2: This will include inflation and construction industry price pressures which were not foreseeable at the time of the OBC.

Note 3: The Department informed us that uplifting the OBC estimated cost (£799 million) to a 2017 base year using Bank of England inflationary indices gives a revised cost of £975 million.

Note 4: The approved FBC figure (including sunk costs) has been uplifted by £10.6 million delay costs incurred in relation to an unsuccessful legal challenge.

Note 5: In 2016 the Desertcreat Flagship project (a combined public services college for NIFRS, PSNI and the NI Prison Service) was re-designated as the Northern Ireland Fire and Rescue Service Learning and Development Centre project at Desertcreat, with a capital cost of £44.8 million

Note 6: DfC told us that, in the absence of Ministers, it is impossible to estimate construction start and completion dates.

Note 7: DfC told us that, in the absence of an OBC or Ministers, it is impossible to estimate construction start and end dates.

Note 8: DfE explained that the final cost figure includes £25.2 million relating to additional planned works around Frederick Street and Block BA BB. Excluding these costs reduces the overspend to £84.6 million (33%). These figures also include £60.6 million Value Added Tax (VAT) which is irrecoverable.

Note 9: DfE told us that if the planned changes of £25.3 million are excluded, the estimated overspend percentage reduces to 29.5 per cent.

Note 10: DE told us that this figure did not include an allowance for inflation.

Part Two: Roles and responsibilities relating to Major Capital Projects

Many Northern Ireland public bodies have a role to play in the commissioning and delivery of major capital projects

2.1 While individual departments remain accountable for the major capital projects they commission and fund, responsibilities for policy, strategy approval and guidance in Northern Ireland fall across several bodies including the Procurement Board, SIB and DoF. A summary of the role of each of these is provided in Figure 2.1. Arrangements within the Department for Infrastructure vary, it operates through three Centres of Expertise (see paragraphs 2.2 to 2.8).

Figure 2.1: Central Roles and Responsibilities in delivering major capital projects

The Procurement Board

- Responsible for the development, dissemination and co-ordination of public procurement policy and practice across Northern Ireland public bodies.

The Procurement Board is Chaired by the Finance Minister and comprises the Permanent Secretary of each of the departments, seven external advisers and the Chief Executive of Construction and Procurement Delivery (CPD). A representative from SIB attends as an observer. It is accountable to the Northern Ireland Assembly.

In the absence of the Finance Minister, the Procurement Board, chaired by the Head of the NI Civil Service, has continued to meet. Since the collapse of the Northern Ireland Executive, on 9 January 2017, the Board has met on six occasions up to April 2019.

The Strategic Investment Board (SIB)

- Works with departments to produce the Investment Strategy for Northern Ireland (ISNI).

- Plays a role in encouraging interest in projects from private sector to increase competition.

- Maintains the capital projects Delivery Tracking System (DTS) which provides the public and industry with details of individual contracts emerging through the government’s infrastructure plans (the ‘infrastructure investment pipeline’). All bodies covered by the NI Public Procurement Policy are required to provide up to date information on infrastructure developments, including procurement information, for release on the ISNI Information Portal.

- Places staff in project management and advisory roles within departments/public bodies providing specialist knowledge and skills to support faster delivery of significant projects in an economically and operationally sustainable manner (Appendix 3).

- Statutory bodies are required to have regard to SIB’s advice and facilitate/co-operate in the exercise of its functions.

- In its advisory role to the Executive, it is involved in the planning and prioritising of major investment projects, funding and borrowing and implementation.

The Department of Finance (DoF)

- DoF, as well as maintaining responsibility for managing its own capital projects, has a central role in providing guidance, granting business case approvals and obtaining assurances on the progress of major projects managed by other departments.

- DoF’s core guidance on the appraisal, evaluation, approval and management of procurement policies, programmes and projects is set out in the Northern Ireland Guide to Expenditure Appraisal and Evaluation (NIGEAE).

DoF Supply Division

- DoF (through its Supply Division) is required to approve project business cases where departments intend to incur expenditure on:

- IT projects over £1 million; and

- other capital projects involving over £2 million central government expenditure (unless other delegations specifically allow).

Construction and Procurement Delivery (CPD)

- Provides advice to Northern Ireland departments and ALBs.

- Provides training to CPD customers.

- Engages with the construction industry.

- Plays a role in the All Party Group on Construction which discusses issues affecting the local construction industry, including public procurement processes.

- Provides a project management service to Health and Social Care Trusts and other DoH ALBs taking forward major capital projects (through CPD Health Projects).

- Provides best practice guidance. The CPD project management guidance sets out the requirements for Northern Ireland public sector bodies and promotes a structured approach based on tested methods and processes. The guidance covers:

- Leadership and Responsibility:

Overall responsibility for delivering the project must be vested in a single, responsible and visible individual (the Senior Responsible Owner (SRO)), and as far as possible, the role should be fulfilled throughout the life of the project by the same person. SROs must complete relevant training, for example, CPD’s SRO Master Class.

- Management Methodologies:

The PRINCE2 methodology should be used for project management generally, and for construction projects, the Policy Framework for Construction Procurement should be followed. These methodologies should be applied proportionately.

- Skills and Experience:

It is important that people leading, managing and working on projects are able to carry out their roles effectively. In addition to being clear about their responsibilities, staff must have the relevant competencies (through experience and training) associated with their role.

- Integrated Assurance Process (IAP)

A series of Gateway Reviews which are mandatory for all infrastructure projects with a capital value of £20 million or more. The reviews, undertaken at key points throughout project planning and delivery, are carried out by an experienced and impartial review team. Review reports provide recommendations and a ‘Delivery Confidence Assessment’ using Red, Amber and Green (RAG) ratings, indicating the potential for successful delivery.

Exceptionally, the Department for Infrastructure operates through three Centres of Procurement Expertise (CoPEs): Roads and Rivers; Translink; and Northern Ireland Water

2.2 The Department for Infrastructure (DfI), with responsibility for maintaining roads, public transport and water and sewerage infrastructure, manages the largest capital budget within the Northern Ireland Civil Service. In 2018-19, DfI’s capital budget was almost double that of the next largest department (the Department of Health (DoH)). DfI was responsible for four of the seven Executive flagship projects, all being delivered simultaneously.

2.3 DfI operates through three independently-assessed Centres of Procurement Expertise (CoPEs): Roads and Rivers; Translink; and Northern Ireland Water. All three CoPEs were accredited in 2018 and, like other CoPEs, comply with NI, UK and EU public procurement best practice and legislation.

2.4 Roads and Rivers CoPE is responsible for construction and specialist supplies and services procurement. Translink and NI Water CoPEs handle all procurement for their business with the exception of collaborative contracts. More common and collaborative contracts are procured through a Service Level Agreement with DoF CPD.

2.5 DfI assesses projects using the Gateway Process and Project Assessment Review (PAR). Projects are managed along PRINCE2 principles and notified to the ISNI Delivery Tracking System. DfI maintains close contact with CPD, SIB and the construction and consulting industries.

2.6 A review commissioned in 2015, undertaken by the Cabinet Office Major Projects Authority, concluded that DfI had “well established and effective appraisal, reporting, evaluation and governance processes in place” and noted that officials could “have a high degree of confidence that projects are being managed, monitored and procured in line with Central Government guidance”. The report highlighted that “in the familiar ‘standard’ delivery areas such as road building, rail and bus infrastructure, water pipe laying and waste water treatment… officials in the relevant delivery organisations …have, over time, built up a considerable track record of project development, cost assurance, delivery and monitoring experience and expertise.

2.7 The Cabinet Office highlighted that there was no reason for complacency, identifying that some issues remained around cost estimate processes and the interface between delivery organisations and DfI which needed to be addressed. It also highlighted that the governance arrangements around novel, complex or non-standard projects may require more careful planning and consideration. While beyond the scope of the Cabinet Office report, it reported the views of almost all stakeholders consulted that the annual budgeting cycle has “an adverse impact on the planning, effectiveness, efficiency and value for money derived from major capital programme delivery”.

2.8 Following the review, DfI established a Major Projects Committee, chaired by the Permanent Secretary, which meets quarterly to maintain oversight of DfI’s delivery of major projects.

In 2012 the Procurement Board initiated a review of the commissioning and delivery of major infrastructure projects in Northern Ireland

2.9 In 2012 the Procurement Board initiated a review (undertaken by SIB) of the commissioning and delivery of major infrastructure projects in Northern Ireland. The review, published in October 2013, found that, “despite there being areas of good practice and effective delivery within the commissioning and delivery system, and despite the best efforts of able and hard-working staff, the system as a whole is not fit for purpose and works against…. best endeavours to deliver”.

2.10 The review concluded that change was necessary to all parts of the current system and that “the system needs to be overhauled and reformed in order to enhance its efficiency and effectiveness, and to ensure that it delivers better value for money for taxpayers”. The review team considered that there was “a real opportunity ….. for the Executive to build a high performance commissioning and delivery system for procuring the infrastructure which Northern Ireland needs”.

2.11 The report identified the need to:

a. strengthen political direction of the commissioning and delivery system in order to give a clear lead and build a sense of common purpose;

b. ensure effective alignment of the government departments and agencies involved in operating the commissioning and delivery system;

c. strengthen the focus on strategic planning and prioritisation of infrastructure investment in order to get the right infrastructure in the right place at the right time;

d. shift the balance to focus more on ‘within budget’ and ‘on time’ delivery of infrastructure assets, rather than having a disproportionate emphasis on inspection, scrutiny and accountability;

e. gather time and cost metrics and benchmarking data, and use them effectively in operational activities;

f. remove inefficient, wasteful and bureaucratic processes;

g. focus on the provision of well-designed, fit-for-purpose infrastructure that meets operational needs, improves operational efficiency and provides good value for money;

h. drive better deals though our procurement activities, while reducing the time, effort and money costs of those activities;

i. strengthen our overall project delivery capability;

j. reform and improve the planning approval process for major infrastructure projects; and

k. ensure that the local construction sector and its representative bodies play their part in helping us to deliver.

SIB’s report to the Procurement Board concluded that the ‘decentralised’ model reinforces departmental silos, increases competition in the prioritisation of projects, makes it more difficult to generate efficiencies through economies of scale and incurs additional costs

2.12 SIB highlighted that while the decentralised model in place in Northern Ireland ensures close working with the client, enabling knowledge and experience of ‘what works best’ in a particular area to be built up, it:

- reinforces departmental ‘silos’ and leads to fragmentation of both the government client base and of procurement expertise and resources;

- fosters greater competition in the planning and prioritisation of capital programmes and creates difficulties in achieving compliance with over-arching and cross-departmental procurement policies and processes;

- makes it more difficult to leverage the scale of government demand for construction works and services to drive better procurement deals; and

- leads to higher costs due to the large number of procurement operations across government, and the risk of ‘gold-plating’ assets as a result of over-specification and non-standard designs.

2.13 The report recommended adoption of a centralised model to cut across departmental ‘silos’, concentrate procurement expertise and resources, create a stronger position for engaging the market and reducing overhead costs. The report concluded that such an approach would facilitate planning and prioritisation of capital programmes; compliance with over-arching policies; and standardisation of procurement processes and documentation. In addition, the report considered that such an approach would facilitate the use of time and cost metrics and benchmarks, and standard designs and specifications, likely to lead to reduced construction costs. Finally, the report highlighted that the centralised approach would make it easier to pursue integrated approaches to service provision, through cross-departmental and cross-public sector infrastructure initiatives like service hubs, planned communities and urban regeneration schemes. The report recommended that the first priority should be to centralise the construction procurement functions of CPD and those CoPEs mainly involved in procuring buildings of various types, before including those mainly involved in procuring civil engineering type construction (that is, DfI CoPEs), which are “more specialist and are currently working reasonably well”. In line with this recommendation, in October 2014, the Department of Health transferred the construction and procurement elements of its Health Estates Investment Group, to CPD. Since then, the newly formed CPD Health Projects has provided a project management service, managing major construction projects on behalf of the Health and Social Care Trusts and other DoH ALBs.

Following publication of the report, a sub-group was created to consider the findings

2.14 On receipt of SIB’s final report in November 2013, the Procurement Board established a sub-group comprising the Permanent Secretaries of those departments with high capital spending and chaired by DoF, to consider the findings. The sub-group prepared an Action Plan in response to the report’s findings, and concluded that without its implementation “the systemic impediments to the likelihood of the successful delivery of infrastructure projects will remain”.

2.15 Key areas addressed in the Action Plan included:

- the prioritisation key, strategically significant projects;

- the need to establish a more centralised construction procurement service for building projects, including government offices, specialist buildings, health care facilities and educational buildings (excluding new-build social housing projects which are mainly procured by Housing Associations (and therefore not covered by Public Procurement Policy) and civil engineering projects (such as highways, bridges, water treatment works and railways)) which will continue to be carried out by the DfI CoPEs operating under a common set of performance and reporting procedures; and

- a move, within departments and their sponsored bodies, to a delivery-focused culture.

2.16 In June 2014, the Action Plan received support from the external members of the Procurement Board and some departments. However, a number of Board members stated that their Ministers reserved approval considering that the matter should be presented to the Executive. The Finance Minister wrote to Executive Colleagues in September 2014 seeking endorsement of the Action Plan, and the plan was referred to in a ‘Dear Accounting Officer’ letter of December 2014. One Minister was not content to support the Action Plan and a further four Ministers were yet to confirm their position when, in April 2016, DoF initiated a Review of the Action Plan. In the event, the Action Plan was not submitted to the Executive for approval.

2.17 The Review Team, comprising senior staff (including the Chief Executive) from the IPA, was to consider whether the Action Plan was the correct approach to improving the delivery of infrastructure in Northern Ireland and how the collective working of all key parties could be improved. While the Review commenced, it did not progress.

2.18 In 2016, DoF identified that, although it had progressed a number of the actions for which it had responsibility, progress against the remaining actions had stalled and, consequently, the improvements to infrastructure are not being realised. DoF told us that CPD staff continue to work with the Construction Industry Forum for Northern Ireland to drive further improvements.

The private sector considers that changing existing arrangements in Northern Ireland could realise efficiencies

2.19 A 2013 report by the Confederation of British Industry (CBI) commented that various changes were required to Northern Ireland arrangements to enhance the ability of the public sector to deliver value for money projects. These included the need for:

- more intelligence-led commissioning of infrastructure – calling, where necessary, on appropriate skills from the private sector to inform prioritisation;

- a change from the process-driven culture – focusing more on user need and potential benefits;

- more realistic project budgets – the quality of the product, outcomes and lifetime costs must account for a larger part of the awarding criteria; and

- prioritisation of turnkey solutions – for example, adopting common designs for building each school or each hospital. In addition, bundling of projects, with specific frameworks in place to ensure that small contractors are not excluded, can realise efficiencies.

2.20 In line with the findings of the SIB review, the CBI report recommended that Northern Ireland follows best practice elsewhere (Scotland and the Republic of Ireland) by creating a new centralised procurement and delivery agency to develop and deliver infrastructure. It envisaged that the new agency would bring together existing structures, with appropriate skills for relevant sectors brought in as necessary to create a critical mass of capability. Projects commissioned by departments would be delivered by the new agency. The report anticipated that such an approach has a number of benefits:

- providing a pool of expertise;

- providing a clearer pipeline of works across all government departments;

- delivering better productivity for capital spend;

- offering a clearer focus on delivery within budgetary envelopes and realising efficiencies;

- streamlining and improving commissioning, procurement and delivery; and

- potentially reducing the risk of judicial review.

In 2016, the Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development recommended an evaluation of the roles of the Procurement Board, CPD, SIB and commissioning entities

2.21 A 2016 report by the Organisation of Economic Co-operation and Development (OECD) identified the importance of eliminating duplication in administrative functions and institutional frameworks to drive efficiency. The OECD recognised efforts in Northern Ireland to ensure efficiency in major infrastructure procurement, including the creation of a centralised procurement and delivery service in CPD (following the transfer of the relevant part of the Health Estates Investment Group in 2014), the simplification of pre-qualification processes, the standardisation of terms and conditions for contracts across the government and the implementation of eTendersNI.

2.22 However, it concluded that the need to better respond to the procurement needs of government, focusing on value for money and achieving efficiency, has not been matched by the development of new procurement approaches or the adoption of new solutions. The OECD identified ‘aversion to risk’ as the main factor slowing process innovation and recommended pursuing greater use of information systems and actively engaging with stakeholders to improve innovation and services, while reducing risks in procurement.

2.23 While all public bodies involved in construction projects must have access to the right mix of professionalism in procurement and construction, the OECD highlighted that developing expertise across numerous departments is duplicative and costly. During the OECD research, interview participants expressed a range of views about the relationship and potential for overlap between the work of CPD and SIB. The OECD identified that roles and responsibilities of stakeholders in procurement need to be clarified. In major procurement projects, the Procurement Board, CPD, the SIB and commissioning entities all have a role to play. The OECD commented that this can appear duplicative, undermining effectiveness and efficiency gains.

2.24 The OECD made the following recommendations:

- Evaluate, with relevant stakeholders, agenda-setting for the Procurement Board;

- Address perceived risk aversion to empower innovative decisions;

- Develop further the role of officials responsible for commissioning procurements;

- Lever existing successes as pilots to cross silos; and

- Clarify and harmonise the roles of relevant stakeholders in the commissioning and delivery of major infrastructure projects.

Conclusions and Recommendations

2.25 A series of reviews of the roles of the Procurement Board, CPD, SIB and commissioning entities have highlighted that current commissioning and delivery arrangements in Northern Ireland are not fit for purpose and have identified the need to:

- eliminate duplication in administrative functions and institutional frameworks;

- improve project prioritisation;

- reduce bureaucracy by focusing more on ‘within budget’ and ‘on time’ delivery, rather than on process; and

- drive better deals by increasing innovation.

2.26 We fully endorse these recommendations. While we note the transfer of the relevant part of the Health Estates Investment Group to CPD in 2014, it is disappointing that further progress in transforming commissioning and delivery arrangements in Northern Ireland has not been made.

2.27 We agree that there is significant merit in considering how alternative models, resourced with sufficient, highly skilled staff could improve future infrastructure delivery by supplementing public sector skills with those available in other sectors and streamlining processes. We recommend that the potential benefits of alternative models are fully explored as a matter of priority.

Part Three: Departmental Management of Major Capital Projects (including

Flagship Projects)

Over the period April 2011 to March 2019, the Northern Ireland public sector major capital project portfolio consisted of 54 projects with a total value of almost £5.5 billion

3.1 We used information held by the Supply Division (within DoF) to identify major capital projects (capital projects with budget approval over £25 million, and excluding programmes, grant schemes and housing association projects) which commenced during the period 1 April 2011 to March 2019. We issued that information to all departments and asked each to ensure the information was complete and accurate, to supplement the list with major capital projects approved prior to April 2011 but completed during this period and to provide information on the progress of each project. The final list of major capital projects, verified by departments, contains details of 54 projects with an original estimated cost of over £5.5 billion (Appendix 4). While we note that a number of projects have suffered time delays and cost overruns, we recognise that several projects completed over the period examined were delivered on time and within budget.

The Department for Infrastructure and Department of Health are responsible for over half of these major capital projects

3.2 Over the seven year period to March 2019, the majority of the major capital projects (61 per cent by number and 72 per cent by cost) were managed by two departments - the DfI and DoH (Figure 3.1).

3.3 The DfI reported the largest major capital project portfolio, 17 projects (31 per cent of the total) with a combined cost of £2.4 billion (43 per cent of the total). The majority of the DfI projects relate to roads and transportation including, for example, four of the Executive’s flagship projects: the A5 and A6 roads (Case Studies 1 and 2 at Appendix 1); the Belfast Rapid Transit (Case Study 3 at Appendix 1); and the Belfast Transport Hub (Case Study 4 at Appendix 1).

3.4 The DoH reported 16 major capital projects (30 per cent) with a combined estimated cost of £1.6 billion (29 per cent). The majority of DoH major capital projects within the Health and Social Care Trusts or its Arm’s Length Bodies are managed using the project management services of CPD Health Projects and typically involve creating additional or replacement facilities, for example, the two Executive flagship projects: the Mother and Children’s Hospital and the Northern Ireland Fire and Rescue Service (NIFRS) Learning and Development Centre at Desertcreat (Case Studies 5 and 8 at Appendix 1).

3.5 The DoH told us that while it is continuing to invest in flagship and other projects which were contractually committed in line with previous Ministers’ strategic priorities, the funding envelope and single year budget environment has not allowed any significant new investments to progress in recent years. It is currently developing a strategic assessment of its long term capital priorities, with input from Health and Social Care Trusts and other ALBs, which will be subject to endorsement by an incoming Minister.

Despite the existence of good practice, access to expertise and mechanisms for facilitating lesson learning, departments still struggle to deliver major capital projects within the timescales and costs anticipated in original business cases

3.6 While representatives attending our focus group acknowledged that there is extensive guidance available in relation to managing major capital projects, and that the experience and skills available within SIB, CPD and individual Centres of Procurement Expertise (CoPEs) can be relatively easily accessed, we found that some departments still struggle to deliver major capital projects within budget and on time.

3.7 Our high level review (see paragraph 1.16) of projects identified that many of the issues identified in previous reports continue to impact on the successful delivery of major capital projects in Northern Ireland. Figure 3.2 highlights the reasons for cost overruns and time delays on specific projects. Details of individual projects are provided at Appendix 1.

3.8 The DfI Belfast Rapid Transit project was the only project we examined which has been delivered within the estimated costs outlined in the initial business case (although the final cost slightly exceeded the cost outlined in the full business case). In relation to the other flagship projects to date, none have been delivered within original timescales or within budget. We noted however that:

- DfI expects that two (of the three) elements of DfI’s flagship A6 project are expected to be delivered for close to, or less than, the estimated full business case cost and within one year of the estimated timescale. The third element of the overall project has been put on hold.

- Two projects of the Regional Stadia Programme (Case Study 9 at Appendix 1) were delivered within budget and broadly within time estimates.

3.9 Latest departmental estimates for flagship projects indicate that:

- Costs for the A5 will exceed the outline business case costs by 38 per cent and delivery will be 10 years later than expected;

- Costs and delivery timescales for both elements of the Mother and Children’s Hospital project will be exceeded. The Regional Children’s Hospital is due for completion by 2025 (five years later than the date specified in the outline business case) at a cost of £353.9 million (59 per cent higher than the original business case cost including inflation and construction price issues). The Maternity Hospital is due for completion in 2021 (six years later than anticipated in the outline business case) at a cost of £73.9 million (29 per cent higher than the outline business case cost, but in line with the FBC which will have fully incorporated inflation and construction price changes).

- Three years after the original expected completion date, the Casement Park Stadium project has yet to begin. Casement Park Stadium costs are expected to exceed original estimates by £32.5 million (42 per cent). While one year after the expected completion date, the Sub-Regional Stadia Programme for Soccer has not yet begun. The likely revised cost of this programme is not yet known.

3.10 In relation to the additional four projects we examined, none have been delivered within envisaged timescales. We noted that:

- While delivery of the Primary Community Care Centres (PCCCs) (being delivered by an alternative delivery approach ‘third party development’ (or 3PD)) has been delayed by over five years, the agreed unitary payment for the Lisburn PCCC is less than that anticipated in the Business Case. DoH expects that the Newry PCCC will be in a similar position.

- The Critical Care Centre is now expected to be completed eight years later than originally expected at a cost of £151.7 million (60 per cent in excess of the original business case estimate).

- The Ulster University, Greater Belfast Development is now expected to be delivered three years later than the originally expected at a cost of £363.9 million (43 per cent in excess of the original budget).

- The Strule Shared Education Campus is now expected to be completed four years later than originally expected at a cost of £213.7 million (27 per cent in excess of the original budget).

3.11 Figure 3.2 shows that the main issues causing delays or changes to the projects include:

- the need to substantially change the scope of the project to ensure more efficient use of resources (NIFRS Learning and Development Centre at Desertcreat);

- funding constraints (affecting a number of projects);

- legal challenges to the A5 and A6 projects at planning and during construction; and

- the time taken to get planning approval for the Belfast Transport Hub and Casement Park Stadium (part of the flagship Regional Stadia Project).

3.12 In the four additional projects we examined (other than flagship projects) the main causes of delay included:

- funding restrictions led to the exploration of alternative funds for the Lisburn and Newry Primary Community Care Centres project. It was hoped that this would avoid delays associated with awaiting conventional capital funding however, both projects still suffered delays;

- limited interest from the construction sector in Strule Shared Education Campus project. One company reported that it would not be submitting a tender against the backdrop of the political difficulties following the collapse of the NI Executive in January 2017. Given that this left only one bidder in the procurement process, the department took the decision to suspend the competition; and

- construction issues have led to major re-working and consequent delays in both the Critical Care Centre and the Ulster University, Greater Belfast Development.

3.13 We intend to keep the progress of the flagship and other projects we examined under review.

Attendees at our focus group highlighted problems they have encountered which impact on the cost and timing of major capital project delivery

3.14 Members of our focus group (see paragraph 1.2) confirmed that a reduction in the capacity and interest of the local construction sector has impacted on their ability to deliver projects. They highlighted that, in their experience, some Northern Ireland construction companies focus their attention on work in England and the Republic of Ireland, where capital build has more buoyancy than in Northern Ireland.

3.15 While accepting the need for the business case process, members told us it can add significant time and cost due to layers of review involved, queries on aspects other than key factors and the need to produce detailed updates to reflect changes.

3.16 Members also mentioned that the increasing appetite in Northern Ireland to challenge procurements and decisions (the latter through Judicial Review), whether successful or not, can result in the need to revise plans, refresh environmental impact assessments and re-work business cases for approval. This view was echoed by the Construction Employers Federation. We intend to carry out an audit of the Northern Ireland Judicial Review process during the 2020-21 financial year.

3.17 Other concerns raised included:

- funding uncertainty beyond the current year/budgeting period makes planning and scheduling for future projects problematic; and

- the absence of a local assembly is beginning to impact on the pipeline of delivery.

Conclusions and Recommendations

3.18 The Northern Ireland public sector faces significant challenges delivering against its major capital projects portfolio. From our high level overview of a number of projects and our focus group, we identified that challenges typically include funding difficulty or uncertainty, challenges through the courts, delays with planning or a lack of appetite and capacity within the local construction industry to take on public sector work.

3.19 Although in 2015, the Northern Ireland Executive identified a number of flagship projects and prioritised these by providing secured funding over the five year period to 2022, we noted that a number have not proceeded as originally planned. Further, where projects have been completed, in many cases, estimated timescales and costs were exceeded.

3.20 Part 2 of this report recommends considering the potential benefits of alternative commissioning and delivery models. We acknowledge that it will take time to identify and select the most suitable model for the future. Given that many of the projects we obtained detail on experienced similar problems, we recommend that, in the interim, contracting authorities collaborate and share best practice.

Figure 3.2 Explanation of Cost Overruns and Time Delays in examined projects

|

Project |

Actual/Expected Over(Under)runs |

Reasons for Cost Overruns/ Time Delays |

|||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

Cost |

Time |

||||||||||||

|

£ million |

% |

Years |

Funding Issues |

Legal Issues |

Planning Issues |

Public Inquiry/Consultation |

Tendering/ Procurement Issues |

Scope Change |

Design Change |

Dependency on other projects |

Site/ Construction Issues |

Environmental/ Archaeological Issues |

|

|

Flagship Projects: |

|||||||||||||

|

A5 (Londonderry, Strabane, Omagh and Aughnacloy)2 |

301.0 |

38% |

10 |

Yes |

Yes |

Yes |

Yes |

||||||

|

A6 |

|||||||||||||

|

Randalstown to Castledawson |

5.0 |

3% |

1 |

Yes |

Yes |

Yes |

Yes |

Yes |

Yes |

||||

|

Dungiven to Drumahoe |

(16.3) |

(7%) |

1 |

||||||||||

|

Caw to Drumahoe (project on hold) |

- |

- |

- |

Yes |

|||||||||

|

Belfast Rapid Transit |

(4.1) |

(4%) |

1 |

Yes |

|||||||||

|

Belfast Transport Hub |

18.3 |

9% |

2 |

Yes |

Yes |

||||||||

|

Mother and Children’s Hospital: |

|||||||||||||

|

Regional Children’s Hospital |

130.9 |

59% |

5 |

Yes |

Yes |

Yes |

Yes |

Yes |

|||||

|

Maternity Hospital |

16.7 |

29% |

6 |

Yes |

Yes |

Yes |

Yes |

||||||

|

Regional Stadia Programme and Sub Regional Stadia Programme for Soccer: |

|||||||||||||

|

Kingspan |

0 |

0 |

0 |

||||||||||

|

Windsor Park |

0 |

0 |

1 |

||||||||||

|

Casement Park3 |

32.5 |

42% |

N/K |

Yes |

Yes |

Yes |

Yes |

Yes |

|||||

|

Sub Regional Stadia Programme for Soccer4 |

N/K |

N/K |

N/K |

||||||||||

|

NIFRS Learning and Development Centre, Desertcreat |

|||||||||||||

|

Phase 1 |

0.6 |

14% |

1 |

Yes |

|||||||||

|

Phase 2 (not yet started) |

1.0 |

2% |

3 |

Yes |

Yes |

||||||||

|

Other Projects (Non-Flagship): |

|||||||||||||

|

Critical Care Centre |

56.7 |

60% |

8 |

Yes |

Yes |

Yes |

|||||||

|

Primary Community Care Centres5: |

|||||||||||||

|

Lisburn |

N/A |

N/A |

5 |

Yes |

Yes |

||||||||

|

Newry (2 year build not yet started) |

N/A |

N/A |

>5 |

Yes |

Yes |

Yes |

|||||||

|

UU –Greater Belfast Development6 |

109.9 |

43% |

3 |

Yes |

Yes |

Yes |

Yes |

||||||

|

Strule Shared Education Campus |

44.8 |

27% |

4 |

Yes |

Source: Departments

Note 1: This will include inflation and construction industry price pressures which were not foreseeable at the time of the OBC.

Note 2: The Department informed us that uplifting the OBC estimated cost (£799 million) to a 2017 base year using Bank of England inflationary indices gives a revised cost of £975 million. Using the uplifted figures reduces the overspend to £125 million (13%).

Note 3: In the absence of Ministers, it is not possible to estimate a construction start or completion date.

Note 4: The Sub Regional Stadia Programme for Soccer is pre-Outline Business Case stage, therefore no revision to actual costs and construction dates has been confirmed. The Sub-Regional Stadia Programme for Soccer was not launched prior to the collapse of the Executive in January 2017 and there has been no progress in the programme delivery.

Note 5: The Primary Community Care Centres are being delivered using 3PD.

Note 6: DfE explained that the final cost figure includes £25.3 million relating to additional planned works around Frederick Street and Block BA BB. Excluding these costs reduces the overspend to £84.6 million (33 per cent).

Appendix One: (Paragraphs 1.2, 1.16 and 3.7) Departmental Case Studies

Department for Infrastructure Case Studies:

1. A5

2. A6

3. Belfast Rapid Transit

4. Belfast Transport Hub

Department of Health Case Studies:

5. Maternity and Children’s Hospital

6. Critical Care Centre

7. Lisburn and Newry Primary Community Care Centres

8. NIFRS Learning and Development Centre, Desertcreat

Department for Communities Case Study:

9. Regional Stadia Programme and Sub-Regional Stadia Programme

Department for the Economy Case Study:

10. Ulster University, Greater Belfast Development

Department of Education Case Study:

11. Strule Shared Education Campus

A5

The A5 is one of five key transport corridors identified in the Regional Transportation Strategy for Northern Ireland. Its development will improve strategic links between Londonderry, Strabane, Omagh and Aughnacloy and with the Republic of Ireland.

First identified in 2007, at 55 miles (88 km), it was to be the single largest road scheme undertaken in Northern Ireland. In July 2009, when the preferred route was announced, the cost of the scheme was estimated at between £650 million and £850 million. Construction was originally intended to commence in 2012, with completion planned in 2018. Commissioned in late 2007, the project was brought to the point of construction in August 2012, with a contractor appointed. Delays from that date have been largely due to a succession of legal challenges.

The project was included as a commitment under the Fresh Start Agreement and was recognised as a ‘flagship’ project in the Northern Ireland Executive’s 2016-17 budget, which allocated funding of approximately £230 million to the project over the four years to 2020-21.

Funding Difficulties

At the outset, the project was expected to benefit from a significant funding contribution from the Republic of Ireland Government – up to £400 million. However, due to the financial crisis this was scaled back and £8 million was received from the Republic of Ireland Government in 2009-10 and £14 million in 2011-12. Under the Fresh Start Agreement, in November 2015, the Republic of Ireland Government committed to providing a further £75 million (£25 million each calendar year over a three year period).

In light of the funding shortfall, in February 2012 it was announced that the project would be taken forward in three, more manageable, phases. The total cost of all three phases is now estimated to be around £1.1 billion.

A business case for the full scheme (all phases) was approved by DoF in October 2017. This was developed in conjunction with DoF to facilitate the necessary DoF approvals associated with the phased delivery of the scheme.

At present, only part of the first phase of the project is being taken forward, a stretch of about 15km, between Newbuildings and Strabane, originally estimated at a cost of £168 million. Plans anticipated that construction would commence in 2017 and be completed in 2019, however progress to construction has been stalled as a result of legal challenge. DfI estimates that this element of the project could start in 2020 with completion in 2022 and with projected costs expected to increase to £207 million. Further legal challenge is however likely.

The anticipated timeframe for the remaining phases suggests construction of the second part of phase 1 (Omagh to Ballygawley) between 2021 and 2023 (at a cost of £270 million), with phase 2 (Strabane to Omagh) between 2023 and 2025 (at a cost of £499 million), and the final phase (Ballygawley to Aughnacloy) between 2026 and 2028 (at a cost of £158 million). Delivery of the scheme is dependent upon completion of statutory procedures and availability of future funding.

If achieved, this would represent an overrun of some 10 years in project delivery. Revised costs for these elements of the project are not yet available.

By March 2019, just over £80 million had been spent on the project. The bulk of this relates to development and preparatory work on the project in the form of payments to consultants (£49.7 million) and contractors (£20.5 million), ground investigations (£4 million), services (£1.1 million) and archaeology (£1 million). It also includes £2.9 million land related costs (such as compensation to landowners) and other costs related to public consultations and inquiries (£1.1 million). To date, no actual road building has taken place on site.

DfI has confirmed that it is unlikely that any expenditure on construction works will be incurred in the 2019 calendar year.