Abbreviations

ASB: Aggregated Schools Budget

AWPU: Age Weighted Pupil Units

C&AG: Comptroller and Auditor General

CFS: Common Funding Scheme

Department: Department of Education

DfE: Department for Education

EA: Education Authority

ELB: Education and Library Board

GMI: Grant Maintained Integrated

GSB: General Schools Budget

IAS: Internal Audit Service

IM: Irish-Medium

LMS: Local Management of Schools

MEMRs: Monthly Expenditure and Monitoring Reports

NIAO: Northern Ireland Audit Office

PAC: Public Accounts Committee

VG: Voluntary Grammar

Key Facts

Budget

£1.79 billion: The General Schools Budget in 2016-17

£1.17 billion: The value of the Aggregated Schools Budget delegated to schools in 2016-17

9.3 per cent: The percentage reduction in the General Schools Budget between 2012-13 and 2016-17 after taking inflation into account

Deficits

165: The number of Controlled and Maintained schools with a deficit at 31 March 2017 exceeding £75,000 or five per cent of their delegated budget, whichever is the lesser

£32 million: The total value of deficits accumulated by Controlled and Maintained schools at 31 March 2017

£1.6 million: The value of the largest school deficit at 31 March 2017 (Drumcree College)

Surpluses

471: The number of Controlled and Maintained schools with asurplus at 31 March 2017 exceeding £75,000 or five per cent of their delegated budget,whichever is the lesser

£46.8 million: The total value of surpluses accumulated by controlled and Maintained schools at 31 March 2017

£1.0 million: The value of the largest school surplus at 31 March 2017 (St Louise’s Comprehensive College)

Executive Summary

Introduction

1. The Local Management of Schools, introduced in 1990, changed the way in which schools are funded and managed, by giving Boards of Governors and school principals the autonomy to make decisions on resource allocation and priorities in order to improve the quality of teaching and learning in schools. A Common Funding Scheme (CFS) was implemented in April 2005 in an attempt to establish a system for the funding of all grant-aided schools on a consistent and equitable basis, irrespective of location or management type. Over £1 billion is allocated to schools each year under the CFS.

2. A number of factors impact on the funding allocated to each school, including the number of pupils attending the school; the number of pupils with additional educational or social needs; and the size of the school premises.

3. The Education Authority (EA) requires that Controlled and Maintained schools aim to contain expenditure within their allocated budget. Schools should not accumulate surpluses in excess of five per cent of their delegated budget or £75,000, whichever is the lesser, unless they are being accumulated for specific purposes. Permission for schools to overspend, that is incur a deficit, is subject to an upper limit of five per cent of a school’s budget share or £75,000, whichever is the lesser.

Key Findings

4. Although the amount allocated under the CFS increased in cash terms between 2012-13 and 2016-17, in real terms, that is taking inflation into account, there was a 9.3 per cent reduction in the General Schools Budget during this five year period.

5. Our analysis of schools’ financial position showed that the number of schools with a surplus and the value of accumulated surpluses have fallen in the last five years. During the same period the number of schools with deficits and the value of accumulated deficits have increased. The EA’s 2017-18 Provisional Outturn shows that the value of schools’ accumulated deficits exceeds accumulated surpluses for the first time in 2017-18.

6. We found that accumulated deficits and surpluses for a significant number of Controlled and Maintained schools exceeded five per cent of budget or £75,000, whichever is the lesser. In addition, although surpluses should be utilised within three years and deficits cleared or substantially reduced within the same period, this was not the case, with a large number of schools having significant surpluses or deficits in each of the last five financial years. Similar issues were raised in an independent review of the CFS in 2013 but the issues were not addressed and thus an opportunity to improve the effectiveness of delegation of schools’ budgets was missed.

7. The EA Board established a Surpluses and Deficits Working Group in response to the deteriorating financial position of schools. However, we found that implementation of the Working Group’s action plan, which included 37 action points, has been slow. Only four of the 25 action points, which should have been addressed by 31 March 2017, were addressed by September 2017. The EA advised that 29 of the 37 action points had been implemented by April 2018.

8. This report indicates an environment where there is pressure on school budgets, increasing pupil numbers and schools with sustainability issues. Therefore, it is clear the system is coming close to a tipping point and action needs to be taken as a matter of urgency.

Recommendations

Recommendation 1

The Department of Education, in conjunction with the Education Authority, should undertake a fundamental review of the Local Management of Schools arrangements. This should include:

- a review of the Common Funding Scheme and its funding factors to ensure that it has no unintended consequences for the funding of schools;

- ensuring that appropriate and effective interventions are developed and applied for those schools which continuously exceed their approved budget, in order to reduce the risk of mismanagement of delegated budgets; and

- consideration of whether the current mechanisms for ensuring schools remain in budget need to be strengthened to ensure better financial management. In doing so, the Education Authority should ensure that appropriate support mechanisms are in place, such as financial expertise at Board of Governors and operational level.

Recommendation 2

The Department of Education and the Education Authority should ensure that the action points arising from the Education Authority’s Surpluses and Deficits Working Group and the recommendations contained in the Department of Education’s ‘Internal Audit Review of School Spend’ are implemented as soon as possible.

Recommendation 3

The Department of Education and the Education Authority should reassess and expedite the implementation of outstanding recommendations included in the Northern Ireland Audit Office’s 2015 Report ‘Department of Education: Sustainability of Schools’ and the Public Accounts Committee’s ‘Report on Department of Education: Sustainability of Schools’ published in 2016. In addition to progressing the implementation of these recommendations, the Department of Education and the Education Authority should consider alternative arrangements to facilitate cost savings, such as shared governance structures.

Recommendation 4

The Department of Education and the Education Authority should review the initiatives being developed by the Department for Education in England and consider whether these should be implemented to support schools in Northern Ireland. In doing, so the Education Authority should ensure that its central procurement framework provides best value for money for Controlled and Maintained schools.

Part One: Introduction and Background

Introduction

1.1 The Department of Education’s (the Department) primary statutory duty is to promote the education of the people of Northern Ireland and ensure the effective implementation of education policy. It is supported in delivering its functions by a range of arm’s length bodies, including the Education Authority (EA).

1.2 The EA is responsible for ensuring that efficient and effective education services are available to meet the needs of children and young people, and for supporting the provision of efficient and effective youth services. These services had been delivered by five Education and Library Boards (ELBs) until 1 April 2015.

Northern Ireland Educational Structure

1.3 Northern Ireland has a complex educational structure, with a range of bodies involved in its management and administration.

1.4 Apart from the 14 independent schools which receive no state funding, all schools in Northern Ireland are grant-aided. Figure 1 sets out the number of grant-aided schools funded under the Common Funding Scheme arrangements (see paragraph 1.7), by school type.

Figure 1: Number of Schools by School Type

|

School Type |

Number of Schools 2017-18 |

|---|---|

|

Pre-school |

95 |

|

Primary |

809 |

|

Post-primary |

201 |

|

Total |

1,105 |

Source: Department of Education

1.5 Education services within Northern Ireland are provided by a number of different management types (Figure 2).

Figure 2: School Management Types

|

Management Type |

Number of Schools 2017-18 |

Characteristics |

|---|---|---|

|

Maintained |

495 |

Maintained schools are managed by Boards of Governors which consist of members nominated by trustees, along with representatives of parents, teachers and the EA. These schools are funded through the EA for their running costs and directly by the Department in relation to capital building works. For Catholic Maintained schools, the employing authority is the Council for Catholic Maintained Schools (CCMS). Other Maintained schools are any schools that are not Catholic Maintained. They are typically, but not exclusively, Irish-Medium schools. |

|

Controlled |

495 |

Controlled schools are managed and funded by the EA through Boards of Governors. Primary and post-primary school Boards of Governors consist of representatives of transferors - mainly the Protestant churches - along with representatives of parents, teachers and the EA. |

|

Controlled Integrated |

27 |

Controlled Integrated schools are Controlled schools which have acquired integrated status. |

|

Grant Maintained Integrated |

38 |

Grant Maintained Integrated schools are self-governing schools with integrated education status, funded directly by the EA (the Department, prior to 1 April 2017) and managed by Boards of Governors. The Board of Governors is the employing authority and responsible for employing staff. |

|

Voluntary Grammar |

50 |

Voluntary Grammar schools are self-governing schools, generally of long standing, originally established to provide an academic education at post-primary level on a fee-paying basis. They are funded by the EA (the Department, prior to 1 April 2017) and managed by Boards of Governors. The Boards of Governors are constituted in accordance with each school’s scheme of management - usually representatives of foundation governors, parents, teachers and, in most cases, departmental or EA representatives. The Board of Governors is the employing authority and is responsible for the employment of all staff in its school. |

|

Total |

1,105 |

Source: Department of Education

Funding Framework

1.6 The Local Management of Schools (LMS), introduced in 1990, changed the way in which schools are funded and managed, by giving Boards of Governors and school principals the autonomy to make decisions on resource allocation and priorities in order to improve the quality of teaching and learning in schools.

1.7 Under the provisions of the Education and Libraries (NI) Order 2003 (the 2003 Order), a Common Funding Scheme (CFS) was drawn up to apply to all grant-aided schools under the LMS arrangements. The CFS was first implemented in April 2005 in an attempt to establish a system for the funding of all grant-aided schools on a consistent and equitable basis, irrespective of location or management type.

1.8 In 2013-14 the Minister for Education instigated a consultation process to review the CFS. The Minister’s key area of focus was the need to ensure appropriate targeting of resources to help schools provide support for young people from disadvantaged backgrounds, in order to reduce the level of educational underachievement. Following this consultation exercise, the Minister determined that a £١٠ million fund be set aside for ‘Additional Social Deprivation’; £5.5 million for nursery and primary schools, and £4.5 million for post-primary schools. In addition to this Additional Social Deprivation factor, the CFS for 2014-15 was amended to incorporate two funding streams, one for nursery and primary schools and one for post-primary schools.

1.9 Since it was formed in April 2015, the EA has been the funding authority for Controlled and Maintained schools. Since April 2017, it is also the funding authority for Voluntary Grammar (VG) and Grant Maintained Integrated (GMI) schools. Prior to this, the Department funded these schools.

1.10 A number of factors impact on the funding allocated to each school, including:

- the total amount of the budget allocated to schools, known as the Aggregated Schools Budget;

- the number of pupils attending the school;

- the number of pupils with additional educational or social needs attending the school; and

- the size of the school premises.

General Schools Budget

1.11 The General Schools Budget (GSB) is the total sum to be spent by the funding authority under the terms of the CFS. It consists of:

- The Aggregated Schools Budget (ASB) – total amount delegated to schools under the two LMS funding streams (nursery and primary, and post-primary). The ASB is expected to meet:

- teacher costs i.e. the cost of teacher salaries including short-term sickness absence;

- repairs and building (tenant) maintenance;

- vehicle running costs; and

- non-teacher costs including classroom assistants, administrative and ancillary staff, books and materials, fuel and light, and examination fees.

- Resources Held at Centre – schools may be allocated funding from central funds for certain staff costs such as substitution; Special Education Needs; and other accommodation costs; and

- Centrally Held Resources Attributed to Schools – amounts held by the EA for services provided to schools (but not at an individual school level), for example, home to school transport, school crossing patrols and curriculum advisory and support services.

1.12 Almost £2 billion is allocated to schools each year under the CFS (Figure 3).

Figure 3: General Schools Budgets and Aggregated Schools Budgets

|

2012-13 £ million |

2013-14 £ million |

2014-15 £ million |

2015-16 £ million |

2016-17 £ million |

|

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

General Schools Budget |

1,730 |

1,750 |

1,780 |

1,820 |

1,790 |

|

Aggregated Schools Budget |

1,123 |

1,123 |

1,145 |

1,178 |

1,175 |

Source: Department of Education

1.13 The EA is required to set out the conditions under which the Board of Governors of each Controlled and Maintained school is given delegated authority and its delegated budget. In imposing such conditions, the EA should have regard to any guidance issued by the Department.

1.14 VG and GMI schools have direct control of their finances and the conditions applied to these schools are subject to separate arrangements operated under financial memoranda. Any overspend on their annual budget by these schools must be financed by the schools from their own resources or bank overdrafts/loans.

Financial targets and pressures

1.15 The Department’s ‘Guidance on Financial and Management Arrangements for Controlled and Maintained Schools funded under the Common Funding Scheme’ (the Guidance), issued in March 2005, states that these schools should aim to remain within budget, to ensure that financial resources are appropriately managed for the existing and future needs of pupils in the school. The Guidance requires that schools should not accumulate surpluses or deficits in excess of five per cent of their delegated budget or £75,000, whichever is the lesser.

1.16 Although in cash terms the GSB and ASB increased between 2012-13 and 2016-17 (see Figure 3), the GSB decreased by 9.3 per cent and the ASB by 10.4 per cent in real terms (i.e. adjusting for inflation). Schools in Northern Ireland advised us that they are facing financial pressures as a result of costs which are outside their control. These include inflationary increases, such as pay rises and higher employer contributions to national insurance and the teachers’ pension scheme. In addition, the number of pupils funded under the CFS arrangements within grant-aided schools increased from over 319,000 in 2012-13 to over 327,000 in the 2016-17 school census year (an increase of 2.5 per cent).

Scope of Report

1.17 This report examines the extent to which schools have been able to manage within their budget for the period 2012-13 to 2016-17 and whether surpluses or deficits are within required limits. The report is structured as follows:

- Part Two analyses the financial position of schools;

- Part Three examines the actions and initiatives being taken by the Department and the EA to address the financial issues facing schools; and

- Part Four sets out our findings, conclusions and recommendations.

1.18 Our study methodology is set out in Appendix 1.

Part Two: Schools' Financial Position

Controlled and Maintained Schools

2.1 The Department’s Guidance states that to ensure that resources are deployed effectively, the Board of Governors of each Controlled and Maintained school is required to agree a financial plan for its school and submit it to the EA for approval. The plan, which should align with the School Development Plan, covers the incoming financial year in detail and the following two years at a level prescribed by the EA. The plan must be consistent with the financial resources available to the school and based on realistic assumptions regarding pupil numbers and income.

2.2 A school’s expenditure should be contained within the approved budget. Large surpluses or deficits must be avoided and schools should aim to remain within budget, thereby ensuring that financial resources are appropriately managed for the existing and future needs of pupils in the school.

2.3 Schools may accumulate savings without affecting the funding they receive in subsequent years. However, the Guidance advises that excessive surpluses should not be accumulated by schools without good reason. Conversely, no school may plan for a deficit without the prior consent of the EA and any school with a deficit will have its budget share in the succeeding financial year reduced by the appropriate amount.

2.4 The Guidance sets an upper limit of five per cent of a school’s budget share or £75,000, whichever is the lesser, for both accumulated surpluses and permitted deficits.

2.5 These requirements have been incorporated into a key performance indicator (KPI) by the EA to ensure schools’ surpluses and deficits are appropriately managed. The EA’s Annual Report and Accounts for the year ending 31 March 2017 shows that only one of the three measures relating to the KPI was achieved in 2016-17 (Appendix 2).

The number of schools with a surplus is decreasing; the number of schools with a deficit is increasing

2.6 In January 2017, the (then) Education Minister advised the Assembly Committee for Education that “…some schools in deficit are, generally speaking, moving into bigger deficits and, for the most part, the schools that are in surplus are moving into decreasing levels of surplus.”

2.7 Between 31 March 2013 and 31 March 2017, the number of Controlled and Maintained schools with a surplus fell from 856 to 711. Conversely, the number of schools in deficit increased from 197 to 315 during the same period (Figure 4).

Figure 4: Controlled and Maintained schools in surplus and deficit 2012-13 to 2016-17

|

Year |

Schools in Surplus |

% of Schools in Surplus |

Schools in Deficit |

% of Schools in Deficit |

|---|---|---|---|---|

|

2012-13 |

856 |

81 |

197 |

19 |

|

2013-14 |

817 |

78 |

217 |

21 |

|

2014-15 |

790 |

76 |

242 |

23 |

|

2015-16 |

785 |

77 |

239 |

23 |

|

2016-17 |

711 |

69 |

315 |

31 |

Source: NIAO analysis of data provided by Department of Education.

Whilst overall schools are in surplus, the value of deficits is increasing

2.8 The GSB and ASB have been decreasing in real terms (see paragraph 1.16) and this has resulted in the net surplus for Controlled and Maintained schools in Northern Ireland falling from a peak of £41.1 million in 2012-13 to £14.8 million in 2016-17. However, the surpluses accumulated by these schools decreased from £55.9 million to £46.8 million. Following an upward trend in the previous three years, there was a marked decrease in schools’ surpluses in 2016-17. However, the value of schools’ cumulative deficits increased consistently over the period, from £14.8 million at 31 March 2013 to £32.0 million at 31 March 2017, an increase of 116.2 per cent (Figure 5).

The number of schools with surpluses exceeding the threshold is reducing

2.9 In the five years to 31 March 2017, the number of Controlled and Maintained schools with accumulated savings in excess of the threshold of five per cent of their budget or £75,000, whichever is the lesser, fell by 151, from 622 to 471 (Figure 6). Nevertheless, this means that 45.9 per cent of Controlled and Maintained schools in Northern Ireland had accumulated surpluses in excess of the threshold at 31 March 2017.

Figure 6: Controlled and Maintained schools’ surpluses compared with the threshold of five per cent of budget or £75,000

|

Year |

Number of schools with a surplus below the threshold |

Number of schools with a surplus above the threshold |

Total number of schools with a surplus |

|---|---|---|---|

|

2012-13 |

234 |

622 |

856 |

|

2013-14 |

262 |

555 |

817 |

|

2014-15 |

246 |

544 |

790 |

|

2015-16 |

254 |

531 |

785 |

|

2016-17 |

240 |

471 |

711 |

Source: NIAO analysis of data provided by Department of Education.

The number of schools with deficits exceeding the threshold is increasing

2.10 In the five years to 31 March 2017, the number of schools with deficits in excess of the threshold of five per cent of their budget or £75,000, whichever is the lesser, increased from 90 to 165, with a marked increase between 31 March 2016 and 31 March 2017 (Figure 7). Consequently, 16.1 per cent of Controlled and Maintained schools in Northern Ireland had a deficit at 31 March 2017 which exceeded the threshold.

Figure 7: Controlled and Maintained schools’ deficits compared with the threshold of five per cent of budget or £75,000

|

Year |

Number of schools with a deficit below the threshold |

Number of schools with a deficit above the threshold |

Total number of schools with a deficit |

|---|---|---|---|

|

2012-13 |

107 |

90 |

197 |

|

2013-14 |

123 |

94 |

217 |

|

2014-15 |

143 |

99 |

242 |

|

2015-16 |

132 |

107 |

239 |

|

2016-17 |

150 |

165 |

315 |

Source: NIAO analysis of data provided by Department of Education.

Accumulated deficits exceed accumulated surpluses

2.11 The EA’s 2017-18 Provisional Outturn reports that the number of schools in surplus at 31 March 2018 reduced to 622, with accumulated surpluses totalling just over £39 million. It also indicates that 396 schools were in a deficit at the end of the 2017-18 financial year, with the deficits totalling £48 million. As a result, 2017-18 is the first year that schools’ deficits outstrip schools’ surpluses.

Some schools have accumulated surpluses and deficits for more than three years

2.12 The Guidance states that the expectation is that any significant savings would be utilised within the period of the three-year budget plan. However, from the data provided by the Department, we identified that for the 1,012 schools which were open for all five years ending 31 March 2017:

- 549 schools had a surplus balance every year, with 288 of these having a surplus in excess of the threshold every year; and

- the closing surplus for 18 schools, whose surplus was in excess of the threshold, had increased year-on-year, with their combined surplus increasing from £1.3 million at 31 March 2013 to £3.1 million at 31 March 2017 - an increase of 138.5 per cent.

2.13 Similarly, any deficits should be cleared or substantially reduced within the period of the three-year budget plan. However:

- 72 schools had a deficit balance for the whole five year period, with 34 of these having a deficit in excess of the threshold every year; and

- the closing deficit balance for 14 schools, whose deficit exceeded the threshold, increased year-on-year, with their combined deficit increasing from £3.7 million at 31 March 2013 to £12.7 million at 31 March 2017 - an increase of 243.2 per cent.

2.14 Of the 72 schools which had a deficit each year for the five years ending 31 March 2017:

- 15 were primary schools with fewer than 105 pupils (the minimum enrolment number for such schools as set out in the Department’s Policy for Sustainable Schools); and

- 12 were post-primary schools with fewer than 500 pupils (the minimum enrolment number for such schools as set out in the Department’s Policy for Sustainable Schools).

2.15 In April 2017 the EA published, ‘Providing Pathways - A Strategic Area Plan for School Provision 2017-2020’ (the Area Plan). The Area Plan sets out the challenges for the education system in Northern Ireland, advising that in some areas of Northern Ireland there are too many school places for the size of the population, while in other areas, there are not enough places. The EA has also published two Annual Action Plans which detail the actions proposed to address the issues identified in the Area Plan. These Annual Action Plans also contain some actions for schools where sustainability is an issue.

2.16 The Annual Action Plan for April 2018 to March 2019 shows that almost one-third of the actions required relate to sustainability issues in 27 named schools. The 27 schools named:

- include only three of the 15 primary schools which had been in deficit each year for the five-year period ending 31 March 2017 and whose enrolment was fewer than 105 pupils; and

- include only one of the 12 post-primary schools which had been in deficit each year for the five-year period ending 31 March 2017 and whose enrolment was fewer than 500 pupils.

2.17 We asked the Department why sustainability was not considered to be an issue for all those schools which had deficits in each of the last five years and which had fewer pupil numbers than the minimum set out in the Department’s Policy for Sustainable Schools. The Department advised that the Policy for Sustainable Schools contained six criteria for assessing school sustainability. While one is finance related, this does not carry more weight than other criterion. Addressing the sustainability of individual schools is a matter for the statutory planning authorities and managing authorities to address in the first instance and through the Area Planning and Development Proposal processes as required.

Post-primary schools have the largest individual surpluses

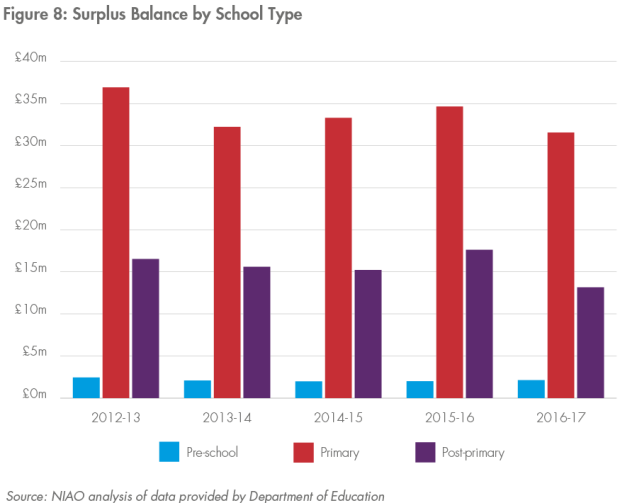

2.18 The annual surplus balance by school type (pre-school, primary and post-primary) remained relatively constant for the five year period ending March 2017 (Figure 8).

2.19 At individual school level, post-primary schools had larger surpluses. The largest individual school surplus at 31 March 2017 was at a post-primary school (St Louise’s Comprehensive College, £1.0 million). This compares with the largest primary school surplus of £0.5 million at St Patrick’s, Dungannon and largest pre-school surplus of £0.1 million (Lisnagelvin Nursery).

Post-primary schools have the largest deficits

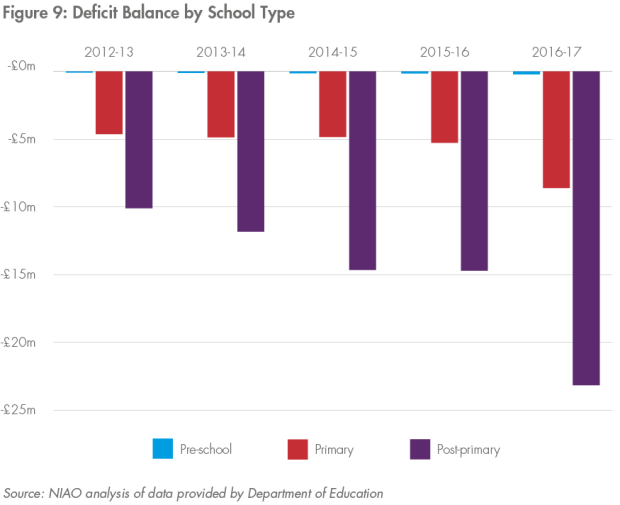

2.20 Prior to 2016-17, the value of pre-schools’ and primary schools’ deficits were relatively constant. However, the deficits accumulated by primary schools increased significantly in 2016-17. Post-primary schools’ deficits increased consistently over the last five years, increasing by almost 129.7 per cent from £10.1 million at 31 March 2013 to £23.2 million at 31 March 2017 (Figure 9).

2.21 Deficits at individual school level were highest in the post-primary schools. Seven post-primary schools had a deficit in excess of £1 million at 31 March 2017, with the largest deficit of £1.6 million at Drumcree College (Figure 10). This compares with the largest deficit at a primary school of £0.4 million (Springhill, Belfast) and a pre-school of £37,000 (St. Anthony’s Nursery, Larne).

Figure 10: Schools with Deficits over £1 million at 31 March 2017

|

School |

Deficit at 31 March 2017£ million |

Number of Pupils |

|---|---|---|

|

Drumcree College |

1.6 |

180 |

|

Strabane Academy |

1.4 |

590 |

|

Crumlin Integrated College |

1.4 |

100 |

|

City Armagh High School |

1.3 |

275 |

|

Coleraine College |

1.1 |

212 |

|

St Eugene’s College, Enniskillen8 |

1.1 |

55 |

|

St Columban’s College, Kilkeel |

1.0 |

156 |

Source: NIAO analysis of data provided by Department of Education.

The largest surpluses are more likely to be at larger schools

2.22 Two schools had accumulated surpluses at 31 March 2017 which were in excess of £700,000. The school with the largest surplus (St Louise’s Comprehensive College, Belfast, £1.0 million) had 1,473 pupils. Holy Cross College, Strabane had 1,539 pupils.

The largest deficits are more likely to be at smaller schools

2.23 Seven schools, all of which were post-primary, had accumulated deficits of more than £1 million at 31 March 2017 (Figure 10), compared with three at 31 March 2016. Only one school of the seven (Strabane Academy) had more than 500 pupils, which is the minimum post-primary enrolment threshold in the Policy for Sustainable Schools.

Voluntary Grammar and Grant Maintained Integrated Schools

2.24 As with Controlled and Maintained schools, Voluntary Grammar (VG) and Grant Maintained Integrated (GMI) schools are allocated fully delegated budgets via the CFS. In 2016-17, the Aggregated Schools Budget for VG and GMI schools totalled £270 million (23.0 per cent of the Aggregated Schools Budget for all schools in Northern Ireland). It should be noted that the majority of VG and GMI schools are post-primary schools and as such they receive a higher Age Weighted Pupil Units (AWPU) cash value under the CFS. Pupils at VG and GMI schools represented 20.2 per cent of the total number of CFS funded pupils in 2016-17 (Figure 11).

Figure 11: Analysis of Schools’ 2016-17 Budgets by Management Type

|

Management Type |

Number of Pupils in 2016-17 |

General Schools Budget £ billion |

Aggregated Schools Budget £ billion |

|---|---|---|---|

|

Voluntary Grammar |

50,322 |

0.24 |

0.21 |

|

Grant Maintained Integrated |

15,907 |

0.08 |

0.06 |

|

Controlled and Maintained schools |

261,340 |

1.47 |

0.90 |

|

Total |

327,579 |

1.79 |

1.17 |

Source: Department of Education

2.25 All schools in the VG sector are post-primary schools, while the GMI sector comprises both primary and post-primary schools (23 and 15 respectively).

2.26 The majority of VG and GMI schools operate as companies limited by guarantee and/or charities, and they all have direct control of their finances. Unlike Controlled and Maintained schools, whose annual funding and outturn positions are included within the EA’s annual accounts, all VG and GMI schools must prepare their own, externally audited, set of annual accounts. They are managed by a Board of Governors appointed in line with each school’s scheme of management.

2.27 Since April 2017, the EA has been the funding authority for VG and GMI schools and as such is responsible for monitoring their expenditure. The EA requests and analyses annual returns from the schools and publishes Annual Outturn Statements for these schools.

VG and GMI schools can retain surpluses but must finance deficits

2.28 Separate financial memoranda for VG and GMI schools set out the conditions and arrangements for the payment of grant-in-aid to these schools. Both memoranda state that any savings made on a school’s budget share will accrue to the school and will not be subject to grant adjustments. The financial memorandum for VG schools also advises that significant surpluses should not be built up, except for a particular purpose; likewise, levels of expenditure should be contained within the total resources available to the school.

2.29 The limits imposed for Controlled and Maintained schools (five per cent or £75,000, whichever is the lesser) do not apply to GMI and VG schools.

2.30 If a VG or GMI school underspends against its budget, the unspent cash is held in a commercial bank account. However, any school overspends against budget must be covered out of the school’s assets, a credit bank balance or, if needs be, by a bank overdraft.

2.31 The cumulative surplus/deficit figures for VG and GMI schools often take account of non-public funds and reflect their individual accounting policies, for example, depreciation and investments. Furthermore, VG and GMI schools do not distinguish between public and non-public income streams in their accounts. Consequently, the financial position of VG and GMI schools cannot be compared on a like-for-like basis with each other or with Controlled and Maintained schools.

The number of VG and GMI schools with surpluses is reducing

2.32 In the five years to March 2017, the number of VG and GMI schools reporting a cumulative surplus fell from 67 to 59, while those reporting a cumulative deficit increased from 20 to 29 (Figure 12).

Figure 12: VG and GMI Schools’ Surpluses and Deficits 2012-13 to 2016-17

|

Year |

Schools in Surplus |

% of Schools in Surplus |

Schools in Deficit |

% of Schools in Deficit |

|---|---|---|---|---|

|

2012-13 |

67 |

77 |

20 |

23 |

|

2013-14 |

63 |

72 |

24 |

28 |

|

2014-15 |

61 |

71 |

25 |

29 |

|

2015-16 |

61 |

69 |

28 |

31 |

|

2016-17 |

59 |

67 |

29 |

33 |

Source: NIAO analysis of data provided by Department of Education.

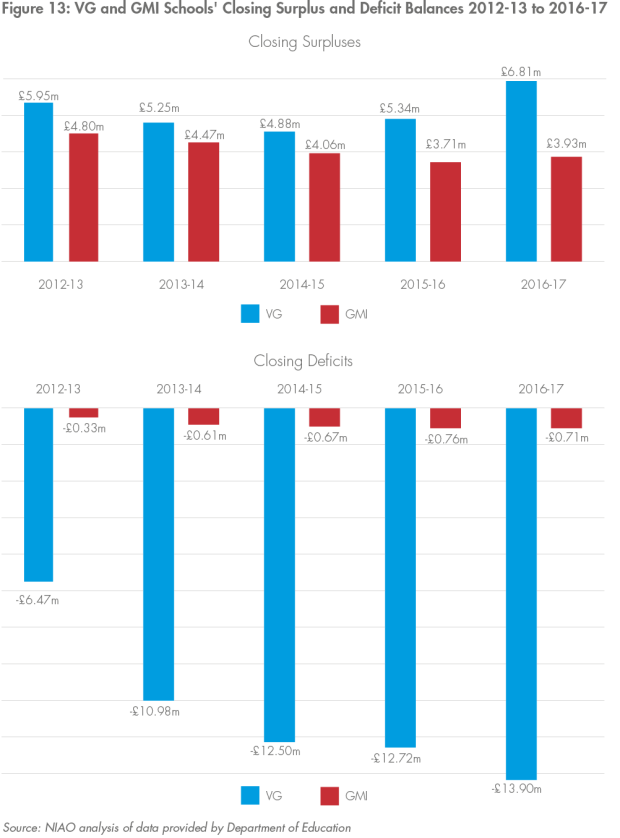

2.33 Between 2012-13 and 2014-15 the total value of VG and GMI schools’ surpluses decreased, but has since increased to £10.74 million at 31 March 2017 (Figure 13), with surplus balances at individual schools ranging from £23,000 to more than £920,000.

2.34 Of the 59 VG and GMI schools in surplus at 31 March 2017, 47 had been in surplus in each of the previous four years.

2.35 The overall value of VG and GMI schools’ deficits increased each year in the last five years, from £6.8 million at 31 March 2013 to £14.61 million at 31 March 2017 (Figure 13). One VG school had a £7.1 million deficit at 31 March 2017. Deficit balances at other VG and GMI schools ranged from £5,000 to £1.2 million at 31 March 2017.

2.36 Of the 29 VG and GMI schools in deficit at 31 March 2017, 13 had been in deficit in each of the previous four years.

2.37 Additional data supplied by the Department indicates that at 31 March 2017, VG and GMI schools had net assets of £428 million and a net bank balance of £46 million. Despite 29 VG and GMI schools having accumulated deficits compared with budget allocation, only one school was overdrawn at 31 March 2017, while none had been overdrawn at the end of the previous financial year.

2.38 We also noted that 22 of the 23 GMI primary schools had a surplus balance every year for the five-year period ending 31 March 2017.

Summary

2.39 Our analysis of financial information provided by the Department and the EA showed that:

- the number of Controlled and Maintained schools with a surplus decreased, while the number of schools with a deficit increased over the five year period ending 31 March 2017;

- Controlled and Maintained schools’ accumulated deficits exceeded accumulated surpluses for the first time in 2017-18;

- the largest surpluses for Controlled and Maintained schools tend to be at larger schools; and

- the number of VG and GMI schools in deficit and the total value of deficits increased in the five year period ending 31 March 2017.

Part Three: The Department's and the EA's response to the financial health of schools

Current Monitoring Arrangements

3.1 As the funding authority for schools, the EA’s role is to monitor the operation of finances in schools; provide them with management information; provide individual schools with statements showing their financial allocations and actual expenditure; operate an audit system to provide assurance that proper controls are in place to safeguard public funds; and apply sanctions, where appropriate, including suspension of delegated budgets. The EA’s role also includes making central provision for significant, unforeseen costs and supporting schools in their delegated responsibilities, for example, a provision to phase in a reduction in teaching complement and class-size funding.

3.2 The EA reports monthly to the Department on the Controlled and Maintained schools through completion of Monthly Expenditure and Monitoring Reports (MEMRs). The MEMRs include details of each schools’ year-to-date expenditure, along with the schools’ estimated and projected spend through to the financial year-end.

3.3 The EA advised us that staff discuss year-to-date expenditure with schools, reviewing this against the schools’ plans, identifying any variances and obtaining explanations and information on the actions which the schools are taking to address the variances.

3.4 The schools’ outturn position and three-year financial plans are analysed by the EA to obtain an understanding of the individual position of each school and the movement in their financial outturn from the previous financial year.

3.5 Each year, the actual outturn position for all schools are published, with the latest Outturn Statements (for 2015-16) published in May 2017 (Outturn Statements - Education Authority), Voluntary grammar schools - 2015/16 outturn statement | Department of Education, and Grant Maintained Integrated Sector - 2015/16 outturn statement | Department of Education.

Sanctions available

3.6 Legislation provides that delegation of the management of a school’s budget share under the Common Funding Scheme may be subject to such conditions as imposed by the EA. In accordance with this legislative provision, the EA may restrict the authority delegated to individual Boards of Governors where it believes that the school cannot operate within the level of resources it has at its disposal. Such restrictions can be used to ensure that planned and actual expenditure are acceptable to the EA.

3.7 The EA advised that, short of suspension of financial delegation, it is constrained in effecting financial restraint on a Controlled or Maintained school and that, to date, the primary avenue for effecting challenge to school management in respect of their financial planning activities has been through direct and formal accountability meetings with either senior officers and/or ELB Board members.

3.8 Legislation empowers the EA to suspend the right to a delegated budget if it appears that the Board of Governors of the school:

- has been guilty of a substantial or persistent failure to comply with any requirement or conditions applicable under the CFS; or

- is not managing the resources put at its disposal for the purposes of the school in a satisfactory manner.

3.9 Where the right to a delegated budget is suspended, the power to determine staffing complement reverts to the EA.

3.10 ‘An Independent Review of the Common Funding Scheme’ (the Salisbury Report), published in January 2013, reported that “…budget delegation has been combined, with very limited accountability for schools. Delegation has never been removed from any school, even where a large and increasing deficit has been incurred.” The report acknowledged that the pattern of large and persistent deficits in part reflected the urgent need for structural changes. However, it indicated that the pattern of deficits raised serious issues about the effectiveness of the existing systems for the financial administration of delegated funds. It warned that a forthcoming real terms reduction in school funding meant the issue was fast becoming critical.

3.11 The analysis in Part Two of this report shows that the issues identified in the Salisbury Report materialised and that, in breach of the Guidance, a significant number of Controlled and Maintained schools have carried a surplus or deficit balance for more than three years. However, to date, delegation has never been removed from any school.

3.12 We asked the Department why the ultimate sanction of suspension of the delegated budget had not been applied, given that a number of schools’ financial position has deteriorated in recent years. The Department advised that suspending financial delegation is not a decision that would be taken lightly and given the complexities of schools funding and governance requires careful consideration of all relevant factors and approval at various levels within EA, DE and at Ministerial level. The sanctions and processes leading up to suspension of schools delegation are currently under review by the Department, in conjunction with the EA.

3.13 The analysis shows that there has been a substantial and persistent failure to manage schools’ surplus and deficit balances in compliance with the scheme requirements. Despite the Salisbury Report raising concerns regarding the increase in school deficits as far back as 2013, no school has had its delegated budget removed. Therefore, in our view, there are no real consequences for, or deterrents against, schools who do not undertake effective financial management of their budget.

The EA established a Surpluses and Deficits Working Group

3.14 In September 2015, the EA’s Finance and General Purposes Committee raised concerns about schools’ aggregated financial outturns and the implications for the EA’s own finances. In response, the EA established a Surpluses and Deficits Working Group to consider how schools in the Controlled and Maintained sectors could be more effectively monitored and supported to achieve consistent budgetary efficiency. The aims of the Working Group are set out in Appendix 3.

3.15 The ‘Working Group Summary Report and Recommendations’ was presented to, and approved by, the EA Board on 15 December 2016. An action plan, which included 37 action points in relation to Working Group’s 25 recommendations, was developed, with priorities assigned to each action (Figure 14). A list of the Working Group’s recommendations is included at Appendix 4.

Figure 14: Surpluses and Deficits Working Group Recommendations and Action Points

|

Number of Recommendations |

Action Point Priority |

Number of Action Points |

|

|---|---|---|---|

|

Managing Surpluses and Deficits |

16 |

Priority 1 Priority 2 Priority 3 |

6 10 9 |

|

Prescribed Thresholds |

1 |

Priority 2 Priority 3 |

3 1 |

|

Governance |

5 |

Priority 2 Priority 3 |

4 1 |

|

Communication |

2 |

Priority 2 |

2 |

|

Bursars |

1 |

Priority 4 |

1 |

|

TOTAL |

25 |

37 |

Source: NIAO analysis of data provided by Department of Education.

3.16 By September 2017 only four of the 37 action points had been implemented.

3.17 Only one of the six Priority 1 action points, which were to be implemented immediately, was completed by September 2017. This involved delivery of fifteen training sessions on LMS financial matters for Governors, which commenced in December 2016 in response to recommendation 2 (see Appendix 4). However, whilst a schedule of training sessions had been agreed for 2017-18, due to budget constraints, courses planned for late 2017 were postponed.

3.18 Only three of the 19 Priority 2 action points, which were to be implemented by March 2017, were completed by September 2017:

- Schools now have full online access to their financial data held on the EA finance system, ensuring that financial information can be made available to principals and governors in a more timely manner. Utilisation of this facility is being considered further by LMS/Senior Finance Personnel (recommendation 11 at Appendix 4 refers).

- Finance reports for schools are generated from the system as part of the month- end procedures, ensuring consistent information is readily available to every school for reporting to their governors (recommendation 12 at Appendix 4 refers).

- A review of surplus and deficit positions and trends for schools, individually and collectively, was carried out and published on the EA’s website in December 2017 (recommendation 17 at Appendix 4 refers).

3.19 The EA advised that the remaining actions are on-going. However, the EA has not set revised implementation dates for the outstanding action points.

3.20 Although the Working Group agreed to reconvene in 12 months, this did not happen and in our view may have contributed to delays in the implementation of the Group’s action plan. We asked the EA why the Working Group’s recommendations had not been implemented in accordance with the timescales set out in the action plan. The EA advised that while the Working Group did not reconvene within 12 months, and there have been some delays in implementing the recommendations, there has been progress in taking forward the recommendations, with 29 implemented as at April 2018. The EA advised that it is actively seeking to implement the remaining recommendations as soon as possible.

The Working Group identified areas for further consideration

3.21 The Working Group identified other areas, beyond its terms of reference, which impact on effective financial planning and where a school’s financial planning may have other consequences (see Figure 15). However, in order to focus on ensuring more effective management of schools’ finances, the Working Group decided not to explore these.

Figure 15: Areas for further consideration identified by the Surpluses and Deficits Working Group

Area Planning

The process for implementing the Department’s Sustainable Schools Policy (SSP). The purpose of the policy is to ensure that children and young people have access to high-quality education that is delivered in schools that are educationally and financially sustainable. In 2015, a Committee for Education position paper14 noted that area planning appeared to have limited impact on the schools’ estate.

Area Learning Partnerships‘

Learning Communities’ bringing schools together to help meet the curriculum Entitlement Framework15. Funding is received by the school where the pupil is enrolled but the costs are borne by the school delivering the curriculum. There is a need to ensure a fair distribution of cost (curriculum delivery) with income (enrolment of pupils).

School Development Plan

A strategic plan for improvement, setting out how a school will raise standards, resource the changes and demonstrate targets and outcomes achieved. The Working Group considered that the connection between a school’s financial plan and its development plan must be further developed.

Policy matters

There is a need to consider policy matters which have a bearing upon a school’s financial circumstances, to ensure that the financial management issues for a school are factored into those considerations. The policy matters to be considered include potential changes in the Common Funding Scheme, earmarked funds and transport.

Resource implications

The group’s recommendations may have resource implications, whether financial or staffing. In progressing the recommendations, consideration should be given to the associated resource implications.

Source: Department of Education

3.22 The ‘Working Group Summary Report and Recommendations’ indicated that the EA’s Finance Committee may wish to see further work being done in relation to these five areas.

3.23 The EA has already been considering some of these other matters. As noted in paragraph 2.15, the first ever Area Plan for Northern Ireland, ‘Providing Pathways - A Strategic Area Plan for School Provision 2017-2020’, was published in April 2017 and the second of three accompanying annual plans was published in April 2018. In addition, the EA has clarified its role in local Community Planning Partnerships. The EA also advised that matters are also being considered as part of wider structural issues and transformation.

The Department commissioned an Internal Audit review of school expenditure

3.24 The Department’s Annual Report and Accounts for 2016-17 indicated that the EA had overspent on its budget allocation for the year ended March 2017. The Department reported that one of the main causes of the overspend was that schools’ delegated expenditure was £7.8 million more than budgeted.

3.25 The Department’s 2016-17 Governance Statement advised that unfunded pay pressures for the previous two years led to more schools accessing surpluses, as they are entitled to do, and to more schools incurring or increasing deficits in 2016-17. Both scenarios had to be funded by the EA in the absence of in-year Monitoring Round bids being met.

3.26 The Comptroller and Auditor General (C&AG) reported on the EA’s actual overspend of £19.1 million compared with its budget as part of his audit of the EA’s 2016-17 financial statements. A copy of his report is included in the EA’s Annual Report and Accounts which were published on 23 March 2018 (http://www.eani.org.uk/_resources/assets/attachment/full/0/75327.pdf).

3.27 As a result of the overspend, the Department commissioned its Internal Audit Service (IAS) to undertake a review of the EA’s systems and capacity to monitor schools’ spend. The IAS was also asked to identify the underlying causes of escalating schools’ spend.

3.28 In their report, issued in March 2018, the IAS made ten recommendations, all of which were categorised as Priority 1. The IAS made two recommendations in relation to strategic issues which impact on the ability to effect change:

- LMS staff advised the IAS that while they can provide advice and guidance to schools, they cannot force financial plans on schools as this is a specific responsibility of the Board of Governors. The IAS recommended that a review of the current LMS arrangements should be undertaken, to determine if changes can be introduced which would ensure that appropriate action is taken if Boards of Governors and principals fail to undertake their financial management responsibilities properly.

- The IAS found anecdotal evidence that the Common Funding Scheme (CFS) allocation of funding for additional circumstances (such as small schools, Targeting Social Need and Newcomers) may be skewing the funding provided to schools and contributing to the build-up of large surpluses at some schools, while the number of schools in deficit is increasing. The IAS recommended that the Department should consider undertaking a review of the CFS.

3.29 The IAS made a further eight operational recommendations, many of which were similar to those contained in the EA Working Group’s report, to help address the growing school deficits (Appendix 5).

3.30 The Department and the EA have accepted all ten of the IAS’s recommendations and target dates for implementation have been set, with the last recommendation due to be implemented by 30 June 2018.

Summary

3.31 Neither the EA nor the ELBs have ever fully utilised the sanctions available under the terms of the CFS.

3.32 Only four of the 37 action points arising from the EA’s Surpluses and Deficits Working Group report had been implemented by September 2017. Twenty-five action points should have been addressed by 31 March 2017 in accordance with the action plan. The EA has advised that 29 of the 37 action points were implemented by April 2018.

3.33 The Department commissioned its IAS to review the EA’s systems and capacities to monitor school spend and identify the underlying causes for the growth of school deficits. The Department and the EA have accepted the need to implement all ten of the strategic and operational recommendations.

3.34 The C&AG reported on the EA’s overspend of £19.1 million as part of his audit of the EA’s 2016-17 financial statements.

Part Four: NIAO Findings and Conclusions

4.1 The majority of schools’ delegated budgets (almost 90 per cent of their net expenditure in 2016-17) are spent on staff costs, with overheads (maintenance, fuel, electricity, books and materials etc.) accounting for the remaining 10 per cent.

4.2 As part of our review, we visited 12 schools to obtain an understanding of the financial issues affecting them and the management of their delegated budget. The schools visited covered all sectors, school types and regions (Appendix 6). In addition, they included schools which had been constantly in surplus and schools which had been constantly in deficit for the last five years.

Staff Costs

4.3 As the majority of staff costs relate to teachers pay, changes in teaching staff will have the most significant impact on a school’s finances. Some schools advised us that they had reduced staff costs by reducing contracted hours for teachers or employing teaching assistants instead of full-time teachers. However, school principals advised us that decisions on teaching staff complements are a matter for the Board of Governors and that managing staffing levels can only be achieved properly if there is sufficient notice of funding, since any attempt to reduce teaching staff will have a lead in time.

4.4 Some schools advised that when their financial position deteriorated, their first response was to cut the hours and numbers of classroom assistants and administrative staff.

4.5 Some principals advised that efforts have been made to reduce staff costs by replacing retirees and voluntary redundancies with staff at a lower point on the pay scale. A pilot of the Investing in the Teaching Workforce Scheme, which aims to encourage teachers over the age of 55 to retire and replace them with recently qualified teachers, allowed 29 teachers to leave between December 2017 and March 2018. The Department advised that a further scheme offering the opportunity for up to 200 teachers to leave will be delivered in 2018-19.

4.6 Sickness absence was an issue for many schools. The latest statistics available from the Department for 2016-17 show that, on average, 9.5 days were lost per teacher due to sickness and that substitution costs totalled £73.6 million. We noted that any costs associated with the first 20 working days of a sickness absence (10 days for schools with four full-time equivalent teachers or less) must be covered by the school’s delegated budget. Principals told us that substitution costs can be as much as £200 per day. Some schools look for substitute teachers at lower grades to reduce the cost impact, while others who cannot afford to bring in substitute teachers, found cover from existing staff or split a class across all other teachers.

4.7 Whilst the approaches adopted by schools may be of financial benefit, they may impact upon the quality of teaching provided by the school and the effective delivery of the curriculum. Reducing teaching staff may lead to increases in class sizes and could result in a reduction in the number of subjects offered in some post-primary schools.

Overheads

4.8 Schools have attempted to reduce their overhead costs. Schools in the VG and GMI sectors regularly tender for contracts including energy, catering, telephone and stationery contracts and as a result have realised savings.

4.9 In the Controlled and Maintained sectors there is less opportunity to make savings, due to centralised procurement. Nevertheless, Controlled and Maintained schools have sought opportunities to reduce overhead costs by cutting back on books and equipment, photocopying and postage. Many schools recognise that the savings they are making are at the margins and feel that the opportunity to make further savings on overheads is limited.

4.10 A number of schools considered the cost of contracts awarded via central procurement to be high. Schools felt that central procurement offered very little value for money and that it restricted their use of the delegated budget. We were told that, although sourcing maintenance locally could be time-consuming, it was significantly cheaper. One school told us that it was able to carpet a classroom from parent/teacher funds for considerably less than the price paid for other classrooms via central procurement. Another school told us that it had arranged its own cleaning contract and halved the price of the EA contract, saving around £30,000.

4.11 In light of schools’ comments, the EA should ensure that the central procurement framework provides best value for money.

Common Funding Scheme

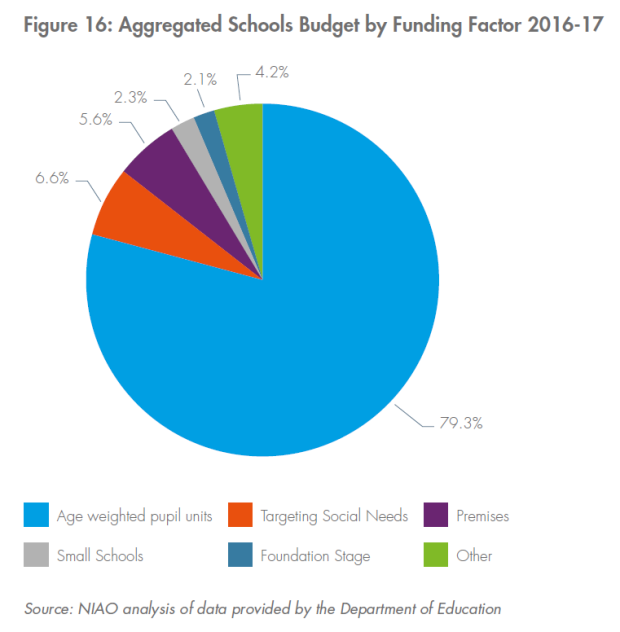

4.12 Almost 80 per cent of the amount distributed in 2016-17 under the CFS was based on pupil numbers (known as the Age Weighted Pupil Units factor) - see Figure 16, while almost seven per cent (£77.6 million) was allocated to schools to Target Social Needs (TNS). Appendix 7 provides a full analysis of amounts allocated under the CFS by funding factor for 2016-17.

4.13 A number of principals raised concerns regarding the outworkings of the CFS. Some principals considered that there needed to be a more even and fair distribution of funding between primary and post-primary schools.

4.14 Schools receive the same allowance per square metre for premises (covering heating costs and maintenance) regardless of the age or condition of buildings. Thus older schools receive the same amount as newer schools which are more energy efficient and which should require less maintenance.

4.15 Some schools feel that medium-size schools lose out as they do not qualify for the Small Schools Support Factor and at the same time do not benefit from the funding associated with having a large number of pupils.

4.16 Some schools advised that their surplus financial position was the result of increasing pupil numbers and additional allowances such as Support for Newcomers, rather than the direct result of their financial management. Similar anecdotal evidence was obtained by the Department’s IAS (see paragraph 3.28).

4.17 The Department should ensure that the CFS and its funding factors do not have any unintended consequences for the funding of schools and consequently their financial position.

School Sustainability

4.18 Linked to these concerns regarding the CFS, a number of schools raised the issue of school sizes and sustainability.

4.19 A number of studies, including ‘An Independent Review of the Common Funding Scheme’ issued in 2013, indicated the need for rationalisation of the schools’ estate, given the number of small schools in Northern Ireland and the additional funding which they attract. The schools visited felt that rationalisation of the schools’ estate would free up more funds for distribution to sustainable schools.

4.20 In June 2015, the Northern Ireland Audit Office (NIAO) published its report ‘Department of Education: Sustainability of Schools’. The report evaluated the progress made by the Department of Education in delivering sustainable schools since the Bain Review in December 2006. Bain concluded that, because of falling pupil numbers and the number of school sectors in Northern Ireland, there were too many schools and that some would become educationally unsustainable. Bain also concluded that the surplus capacity, to cater for a degree of uncertainty in planning and to accommodate parental preference, should not exceed 10 per cent across the schools’ estate.

4.21 The NIAO’s 2015 report noted that, overall, there had been some progress in implementing the Department’s Sustainable Schools Policy through area planning, with the schools’ estate reducing by 89 schools, from 1,133 in 2006 to 1,044 in 2015. By 2017-18, the number of Controlled and Maintained schools had reduced to 1,017.

4.22 The NIAO’s 2015 report also noted that around £36 million of school budgets are allocated to schools because they are small. In 2016-17, £27 million (2.3 per cent of school budgets) was still being allocated to small schools.

4.23 The Policy for Sustainable Schools sets out the minimum enrolment thresholds for primary and post-primary schools. The NIAO’s 2015 report advised that in 2014-15, 36 per cent of primary schools had fewer than the minimum threshold of 105 pupils, while 47 per cent of post-primary schools had fewer than the minimum threshold of 500 pupils in years 8 to 12. Updated figures provided by the Department show that the percentage of primary schools with fewer than 105 pupils had fallen to 32 per cent in 2016-17, while the percentage of post-primary schools with fewer than 500 pupils had fallen to 42 per cent.

4.24 The NIAO’s 2015 report advised that there were 50,389 surplus places in primary schools and 21,151 surplus post-primary school places in 2014-15. We note, based on information contained in the Annual Action Plan for April 2018 to March 2019, there were 35,910 available places in primary schools and 13,718 available places in post-primary schools in 2017-18.

4.25 Following the Public Accounts Committee (PAC) examination of, and an evidence session on, the NIAO’s 2015 report, the PAC published its ‘Report on Department of Education: Sustainability of Schools’ in March 2016, making ten recommendations for the Department’s consideration. The Department’s responses and undertakings in relation to the PAC’s recommendations were set out on the ‘Department of Finance Memorandum on the Thirty Fifth Report from the Public Accounts Committee Mandate 2011-16’ issued in June 2016. Only three of the eight commitments which the Department agreed to undertake have been achieved to date. The remaining commitments are being progressed by the Department.

4.26 We recognise that it will take time to rationalise the number of schools and the political sensitivities associated with it. Therefore we recommend that consideration is given to alternative arrangements to facilitate cost savings, such as shared governance structures, collaborative procurement and clustering of schools.

Financial Expertise

4.27 Some of the schools reported that they lack the financial skills required for day-to-day financial management of their budget. They felt the need to employ professional accountancy support but did not have the resources to do so. VG schools have full- time bursars, while schools within the GMI sector employ bursars on a full-time or part-time basis. At the GMI school we visited, there is a bursar on-site one day per month.

4.28 The Surpluses and Deficits Working Group findings include a Priority 4 action point that the EA should consider developing and piloting a model Bursar Scheme for Controlled and Maintained schools. The EA has indicated that it would be keen to see a pilot bursar scheme developed so that schools would have more dedicated financial management support over and above that presently available from LMS. The EA has undertaken to look at this in due course.

Other Initiatives

4.29 In 2013 the Department for Education (DfE) in England completed a review of school efficiency and undertook to support schools via a number of initiatives:

- effective workforce deployment;

- benchmarking;

- an indicator of school efficiency;

- improved procurement;

- support for clusters of primary schools to take on a school business manager; and

- more effective governance and accountability.

4.30 In January 2016, DfE launched its Schools Financial Health and Efficiency programme. Key elements of the programme include:

- a webpage for the DfE’s guidance and tools;

- a financial health checklist service;

- strategies for workforce, procurement and communications; and

- access to framework contracts.

4.31 We asked the Department whether similar initiatives had been introduced in Northern Ireland. The Department advised that at this time consideration is being given to developing broader benchmarks for use in promoting efficient and effective use of school budgets, extending beyond Pupil/Teacher Ratios, Management Allowances and structures. In addition, schools are presently required to demonstrate evidence of procurement savings if they buy from sources other than EA contracts and also, by virtue of their relationship with the EA, that their procurement activity is within the jurisdiction of EU procurement guidelines.

4.32 The Department also advised that the EA is seeking to establish multi-disciplinary teams working across education, human resources and finance to support schools in the management challenges they face.

Conclusions

4.33 Our analysis of schools’ financial positions in Part Two showed that the number of schools in surplus and the value of surpluses accumulated had fallen in the five financial years 2012-13 to 2016-17. During the same time the number of schools with deficits and the value of accumulated deficits have increased. The EA’s 2017-18 Provisional Outturn shows that the value of accumulated deficits exceeds accumulated surpluses for the first time in 2017-18.

4.34 Accumulated deficits and surpluses for Controlled and Maintained schools exceeded the EA’s Guidance of five per cent of budget or £75,000, whichever is the lesser. In addition, although the Guidance advises that surpluses should be utilised within three years and deficits cleared or substantially reduced within the same period, this was not the case, with a large number of schools having significant surpluses or deficits in each of the five financial years 2012-13 to 2016-17.

4.35 Although the Guidance provides for suspension of a school’s delegated budget and restriction of delegated authority, neither the EA nor the ELBs fully utilised the sanctions available.

4.36 In response to schools’ deteriorating financial positions, the EA set up a Surpluses and Deficits Working Group. However, we found that implementation of the resulting action plan has been slow, with only four of the 25 action points which should have been addressed by 31 March 2017, actioned by September 2017. The EA advised that 29 of the 37 action points had been implemented by April 2018.

4.37 The Department has only achieved three of the eight commitments given in response to the PAC’s report on the Sustainability of Schools.

Recommendations

4.38 The Department, in conjunction with the EA, should undertake a fundamental review of the Local Management of Schools arrangements. This should include:

- a review of the Common Funding Scheme and its funding factors to ensure that it has no unintended consequences for the funding of schools;

- ensuring that appropriate and effective interventions are developed and applied for those schools which continuously exceed their approved budget, in order to reduce the risk of mismanagement of delegated budgets; and

- consideration of whether the current mechanisms for ensuring schools remain in budget need to be strengthened to ensure better financial management. In doing so, the EA should ensure that appropriate support mechanisms are in place, such as financial expertise at Board of Governors and operational level.

4.39 The Department and the EA should ensure that the action points arising from the EA’s Surpluses and Deficits Working Group and the recommendations contained in the Department’s ‘Internal Audit Review of School Spend’ are implemented as soon as possible.

4.40 The Department and the EA should reassess and expedite the implementation of outstanding recommendations included in the NIAO’s 2015 Report ‘Department of Education: Sustainability of Schools’ and the Public Accounts Committee’s ‘Report on Department of Education: Sustainability of Schools’ published in 2016. In addition to progressing the implementation of these recommendations, the Department and the EA should consider alternative arrangements to facilitate cost savings, such as shared governance arrangements.

4.41 The Department and the EA should review the initiatives being developed by the Department for Education in England and consider whether these should be implemented to support schools in Northern Ireland. In doing so, the EA should ensure that its central procurement framework provides best value for money for Controlled and Maintained Schools.

Appendix 1: Study Methodology (Paragraph 1.18)

The study used a combination of quantitative and qualitative methods for gathering evidence, including:

- discussions with key staff at the Department of Education and the Education Authority;

- visits to schools, encompassing primary and post-primary and Controlled, Maintained, Voluntary Grammar and Grant Maintained Integrated schools, and discussions with school principals, bursars and governors;

- review of documentation, including work performed by the National Audit Office and the Assembly Research and Information Service; the Department of Education and Education Authority policies/procedures/guidance; and relevant legislation; and

- data analysis of summarised Monthly Expenditure Monitoring Reports provided for the period 2012-13 to 2016-17.

Appendix 2: Progress in 2016-17 against the EA's objective to ensure that schools' surpluses and deficits are appropriately managed (Paragraph 2.5)

|

Actions / Commitments |

Measures |

Position Report at 31 March 2017 |

|---|---|---|

|

Schools’ deficits managed in line with extant financial guidance. |

In 2016-17, reduction in the number of schools with a deficit that is in excess of five per cent or £75,000, whichever is the lesser, of their delegated budget. |

Not Achieved |

|

Appropriate review of financial plans for schools in deficit. |

Financial plans for those schools already in deficit, or planning to go into deficit in 2016-17, formally approved by the Interim Chief Executive and they clearly show how the school plans to fully recover this deficit within an acceptable time period (no greater than three years). |

Not Achieved |

|

Schools’ surpluses managed in line with extant financial guidance. |

In 2016-17, reduction in the number of schools with a surplus that is in excess of five per cent or £75,000, whichever is the lesser, of their delegated budget. |

Achieved |

Source: Education Authority Annual Report and Accounts for the period ended 31 March 2017

Appendix 3: Aims of the EA's Surpluses and Deficits Working Group (Paragraph 3.14)

The Working Group aimed to identify measures to:

- minimise the risks to the EA and the Department;

- improve schools’ financial planning activities;

- improve the EA’s monitoring of schools’ projected/actual surplus and deficit positions and take appropriate action, where required; and

- ensure that concerns drawn to the attention of a school/Board of Governors receive an appropriate response.

Appendix 4: Recommendations made by the EA’s Surpluses and Deficits Working Group (Paragraph 3.15)

Managing Surpluses and Deficits

1. There is a need for the EA to develop LMS structures which ensure support is consistent across the whole of the EA.

2. Training to be offered to all Governors and Principals on general financial management matters.

3. Specific training programmes to be targeted at schools in like circumstances and with the most significant financial challenges, to focus attention on that which needs to be addressed, with involvement and input from education personnel.

4. To develop financial modelling tools that enable schools to more directly understand the dynamics which may impact upon their individual circumstances.

5. To direct schools to relevant information which is already available to assist in financial planning i.e. demographics.

6. The timely notification of schools’ budgets by the Department to schools.

7. The EA to ensure schools are more accountable in forecasting their financial position by introducing a formal mid-year review of schools’ initial financial plans and all such detail to be signed off by the Board of Governors.

8. To develop appropriate arrangements where education advice and support is available to assist a school’s management in identifying all alternatives for resolving financial difficulties.

9. Officers to develop escalation procedures to ensure that the EA is proactive in ensuring that schools’ actions are in accordance with their circumstances.

10. In ensuring that the reporting of schools’ financial positions are considered at every meeting of Boards of Governors, the EA should review present arrangements which seek to ensure compliance with this objective.

11. Consideration to be given as to how financial information can be made available to Principals/Governors in a more timely manner.

12. To develop advice on the minimum financial information that should be presented to Governors at meetings of the full Board of Governors.

13. To review all Financial Guidance for schools to ensure that it:

i. supports the schools in managing their finances;

ii. supports the EA in discharging its funding authority responsibilities; and

iii. promotes good practice on financial management matters which are educationally focused.

14. LMS budgets must be more effectively managed on an EA-wide basis and officers should review LMS arrangements in relation to:

i. providing financial management advice and support to schools;

ii. considering the budget planning and approvals processes;

iii. the financial reporting arrangements; and

iv. effecting challenges to variations between planned and actual expenditure.

15. To seek to ensure that any earmarked resources are notified to schools as soon as possible.

16. To review CFS funding elements and additional earmarked funds to ensure that:

i. funds were appropriately targeted; and

ii. the intended objectives were being achieved.

Prescribed Thresholds - the lesser of £75,000 or 5%

17. Officers to examine and review the surplus/deficit threshold limits and consider:

i. the appropriateness of the absolute figures for larger schools;

ii. the timeframes within which individual schools are required to address their surplus/deficit above the agreed tolerances; and

iii. officers to develop a model of support that includes educational input in addressing underlying financial management issues.

Bursars

18. The EA to consider developing and piloting a model Bursar Scheme for Controlled and Maintained schools.

Governance

19. The EA should review the mechanics by which schools’ financial plans are approved and consider how approval could be conditional on whatever obligations the EA, as funding authority, considers appropriate.

20. The establishment of an appropriate procedure within the EA for effecting suspension of financial delegation to a Board of Governors.

21. A review of the present engagement arrangements in relation to the annual budgetary cycle, drawing upon financial performance in prior years.

22. A review of the Common Funding Scheme to explore what other avenues may be available to the EA to make schools more accountable for the implications of their operational decisions, in particular, in relation to the management of surpluses.

23. Further work to be carried out on developing appropriate sanctions to be applied to a school when all other avenues, short of the suspension of financial delegation, have been exhausted.

Communication

24. Officers to develop a communications strategy with schools on LMS financial management matters.

25. The development of effective communications aimed at keeping schools informed, and to increase their understanding of the financial issues facing the education system as a whole, as well as that impacting at the individual school level.

Source: Department of Education

Appendix 5: The Internal Audit Service’s Operational Recommendations (Paragraph 3.29)

- It is vital that the EA always approves school financial plans by 30th June. The IAS recommended that progress to achieving this target is reported to the EA Board and the Department.

- Where financial plans are not in line with the financial resources available, the use of Conditional Letters of Approval is deemed appropriate to help ensure schools take action to reduce expenditure.

- Where final budget figures are not available before year-end, planning on the basis of indicative figures should be undertaken.

- The EA should urgently establish a consistent approach to monitoring schools’ financial performance, to include regular monitoring of variances against plans, and a process to deal with circumstances where significant variances against plans are identified.

- Higher risk schools should be required to meet with one of the EA’s Committees to explain the circumstances of their deficit and the actions taken to reduce it.