Definitions and Abbreviations

BRCD: Belfast Region City Deal

C&AG: Comptroller and Auditor General

Capital receipts: Income received when assets (such as land or buildings) are sold. Capital receipts can only be used to buy new or improve existing assets. These assets could be land, buildings or large pieces of equipment such as vehicles.

Capital grants: Sums of money given to councils by the Government. This money can only be used as capital expenditure, to buy or improve assets of lasting value.

CIPFA: Chartered Institute of Public Finance and Accountancy

Department: Department for Communities

Earmarked reserves: Money that has been set aside for a particular purpose, such as buying or repairing equipment, or the maintenance of public parks or buildings.

Emphasis of matter: A paragraph that is included by the Local Government Auditor in her audit report to direct the attention of users of financial statements to a matter that has been discussed appropriately in the financial statements (usually a disclosure). It is a professional judgement that the matter is of such importance that users should know about it in order to completely understand the financial statements.

FTE: Full Time Equivalent

FM Code: Financial Management Code

General Fund balance: This is a contingency fund - money set aside for emergencies or to cover any unexpected costs that may occur during the year, such as unexpected repairs.

NIAO: Northern Ireland Audit Office

Real-term: Real-term expresses the historical value of money in the past, at today’s value. This is because the value of £1 today is less than it was in previous years.

SOLACE: Society of Local Authority Chief Executives

Treasury management: The management of the organisation’s investments and cash flows, its banking, money market and capital market transactions; the effective control of the risks associated with those activities; and the pursuit of optimum performance consistent with those risks.

Usable reserves: This is accumulated, unspent money that each council has set aside from previous years to provide services or buy assets now or in the future.

Unusable reserves: These relate to accounting treatment balances, rather than real usable money. They include, for example, balances relating to ‘unrealised gains or losses’ in respect of assets, such as buildings, whose value changes over time. There may also be commitments linked to these assets such as loans or maintenance needs. The funds held in the unusable reserves fund can only be unlocked and turned into usable money if the assets are sold.

Local Government Auditor’s Introduction

As Local Government Auditor, it is my responsibility to audit and provide an opinion on the financial statements of the 11 councils in Northern Ireland. I am also required to prepare an annual report on the exercise of my functions.

This report provides my perspective on the audits of local councils based on the key messages from audit work completed by 31 March 2020. This includes the audit of the financial statements for 1 April 2018 to 31 March 2019 (the 2018-19 financial year) and the audit of councils’ performance improvement plans and outcomes from 1 April 2019 to 31 March 2020 (the 2019-20 financial year). As such, parts one to three of my report reflect the circumstances councils were operating in prior to the Covid-19 pandemic.

In my report, I have sought to highlight areas of strength and areas for improvement within local councils. I have also considered several important issues that may affect the councils in the near future. Both councillors and officers should consider this report and review how their council is managing the issues I have highlighted.

The Covid-19 pandemic has had a significant impact on all aspects of our lives. Our public services have been particularly impacted as in most cases they are considered to be front line services. Local government responded positively and played its part in ensuring key services have been maintained. The full scale and impact of the ongoing pandemic on communities, local services and the economy is unknown at this stage but is likely to be very significant and place further strain on local government finances.

The Department for Communities (the Department), with the consent of the Comptroller and Auditor General for Northern Ireland (the C&AG), designated me as the Local Government Auditor in January 2018. I am also the Chief Operating Officer of the Northern Ireland Audit Office (NIAO).

In addition to providing an opinion on the financial statements of the 11 councils, I am responsible for the audit of two joint committees, the Local Government Staff Commission and the Northern Ireland Local Government Officers’ Superannuation Committee.

In total, audit opinions are issued on 15 sets of financial statements. I am pleased to report that all 15 audit opinions for the 2018-19 financial statements were unqualified. This means that all financial statements were properly prepared and that they gave a true and fair view of the financial position of the body concerned and its income and expenditure for the year.

Councils are independent of central government and are accountable to their citizens. They consider local circumstances in making decisions in the best interests of the communities they serve. All councils have the same basic legislative responsibilities, although each council has the discretion to place a different emphasis on the services delivered.

In providing such a broad range of services, either directly or in partnership with others, councils require substantial resources. In the 2018-19 financial year they spent over £1 billion on providing services to the public, employed over 10,000 full time equivalent staff and utilised assets worth in excess of £2.5 billion.

As part of my audit work, I consider whether each council has proper arrangements in place to secure economy, efficiency and effectiveness in the use of resources and that public money is properly accounted for. If I consider it appropriate, I can make a report in the public interest on any matter coming to my notice in the course of an audit. No public interest reports were made during the year and my audit findings were issued to each council in their annual audit letter, which is published on councils’ websites, detailing where any action is required. I expect councils to take these actions forward as appropriate.

In addition to the audit of 2018-19 local government financial statements, I am responsible for the audit and assessment of the councils’ performance improvement responsibilities. The work carried out during the year in this area concluded that all councils met their key performance improvement responsibilities, both in relation to improvement planning and the publication of improvement information, and all received the same overall assessment. Although councils are at different stages of development, all strengthened their performance improvement arrangements and each council demonstrated measurable improvements to functions. I have provided feedback to each council on how their arrangements could be further improved.

This was the third year that councils were required to report on their performance against that of other councils in delivering the same or similar functions, where it was reasonably practicable to do so. In my reports I highlighted that significant progress by all councils was needed to allow a broader range of functions to be benchmarked in future.

Given the ongoing impact of Covid-19, the Department has initially suggested consulting councils on performance improvement requirements over the next two years. It has suggested that it may be more beneficial for councils to produce plans setting out their proposals for service delivery and performance recovery, rather than the performance improvement plans currently required by legislation and statutory guidance.

As the Local Government Auditor, I can also undertake comparative and other studies designed to make recommendations for improving economy, efficiency and effectiveness in the provision of services by local government bodies, and to publish my results and recommendations. The NIAO C&AG and I have recently published a joint report on “Managing Attendance in central and local government” which highlighted that levels of absence for councils are the highest in the UK. Our report identified a number of key principles and good practice that should be applied in managing attendance.

I have recently been directed to hold an extraordinary audit of Causeway Coast and Glens Borough Council, concentrating on land disposals and easements and related asset management policies and procedures. I will shortly consider the scope and timing of this audit.

I would like to thank elected members, Chief Executives and staff of the 11 councils and other local government bodies audited, for the assistance provided to audit staff in completing this year’s audits. I also wish to thank those members of staff of the NIAO who assisted me in the performance of the Local Government Auditor’s functions.

Pamela McCreedy

Local Government Auditor

15 December 2020

Council districts

Source: NIAO

Key Facts

In 2018-19 councils:

INCOME

Received income of £917 million – 68% of which was from district rates

EXPENDITURE

Incurred operating expenses of £1 billion and spent £131 million on capital projects

£549m

PENSION

Net pension liabilities increased to £549 million

£527m

LOANS

Had outstanding loan balances of £527 million

£258m

RESERVES

Held usable reserves of £258 million

SICKNESS

Lost an average of 13.93 days due to sickness

Part One: Financial Performance

1.1 This section provides a summary of the councils’ financial performance in 2018-19.

Key Messages

1. The majority of councils’ income is received from district rates.

2. Income and expenditure increased in 2018-19, however there remains a shortfall as the increase in expenditure outweighs the increase in income.

3. As in previous years, some councils continue to be very reliant on agency staff. There is a risk that over-reliance on agency staff, over an extended period of time, does not provide value for money.

4. Usable reserve balances have increased since the formation of the new councils, however General Fund balances in some councils have declined rapidly. Councils should monitor the levels of reserves carefully.

5. Pension liabilities are a cost pressure for all councils and the net pension liability increased by almost 10 per cent to £549 million.

6. Borrowing increased significantly in 2018-19 and substantial amounts are committed to repaying the loans.

7. Robust financial management arrangements are required to aid decision making and ensure long-term financial sustainability.

Income and expenditure

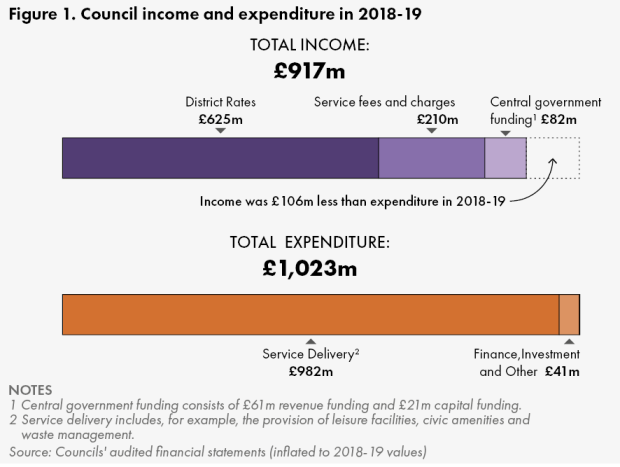

Councils received income of £917 million, the majority of which was from district rates

1.2 In 2018-19, councils received income of £917 million (£862 million in 2017-18) from rates, service charges, grants and investment income and spent £1,023 million (£936 million in 2017-18) (see Figure 1). The total income received is made up of £896 million of revenue-based income, which is spent on the delivery of council functions and services, and £21 million of capital income, which is spent on acquiring or improving new assets, for example leisure centres and play parks. Councils can also spend money from their usable reserves and supplement their income by borrowing money to support capital projects.

1.3 The majority of councils’ income, 68 per cent (70 per cent in 2017-18), was received from district rates. Service fees and charges, for example planning fees or charges to use facilities, and other income accounted for almost 23 per cent of income (22 per cent in 2017-18) and general revenue funding from central government accounted for almost 7 per cent. Capital grants fluctuate from year to year, depending on investment decisions, and in 2018-19 accounted for just over 2 per cent of total income.

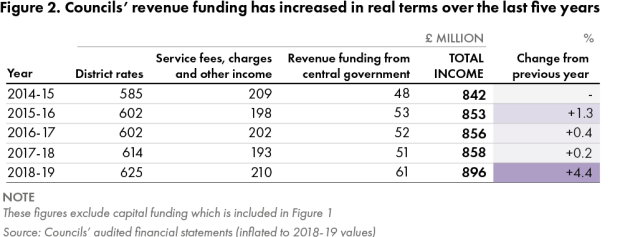

1.4 Overall the local government sector has experienced a real-term increase in revenue-based income over the past five years (see Figure 2), and in 2018-19 income from service fees, charges and central government revenue funding increased having declined in 2017-18.

1.5 In 2018-19 seven of the eleven councils were entitled to a Rates Support Grant at varying levels. It is designed to provide additional finance to those councils whose total rateable value, per head of the population, falls below a standard determined by the Department. The total amount available varies annually, depending on the Department’s spending priorities. As a result of funding pressures the total annual amount allocated to the councils (£17.2 million in 2018-19) has not been reducing (£17.6 million in 2017-18). As with the previous year, the Department has not been in a position to notify councils of the Rates Support Grant until after they have struck the district rates for the year. This makes financial planning more difficult.

1.6 Income levels vary considerably across each council, but all continue to be reliant on income from the district rate. It is important that councils continue to explore options to maximise the income generated from services, and where possible reduce costs, including considering the potential for more efficient service delivery such as online facilities, automated processes and the sharing of services across councils.

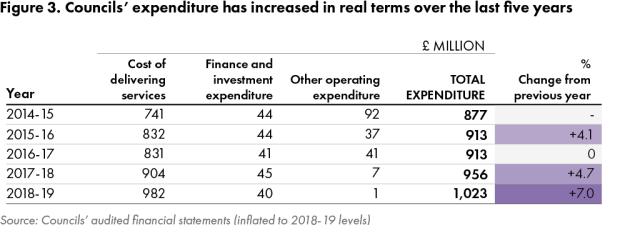

There has been a real-term increase in expenditure

1.7 As with income, expenditure levels vary considerably across each council and overall there has been a real-term increase in expenditure in recent years (see Figure 3). The main areas of council expenditure include the provision of leisure facilities, civic amenities, and waste management.

Observation

Over the past five years, expenditure has exceeded income every year. The shortfall between revenue income (see Figure 2) and expenditure (see Figure 3) has notably increased in the past two years and in 2018-19 the shortfall was £127 million. This may not be sustainable in the longer term and, as noted at paragraph 1.6, councils must continue to explore options to maximise income and reduce costs.

Staffing levels and costs

Some councils spend significant amounts on agency staff

1.8 Council services across Northern Ireland are primarily delivered by a combination of council employees and, to a lesser extent, agency staff. Historically, most agency staff have been temporary and seasonal in nature. Despite it being more than four years since the formation of the new councils there continues to be an increased dependency within some councils on agency staff to help deliver services.

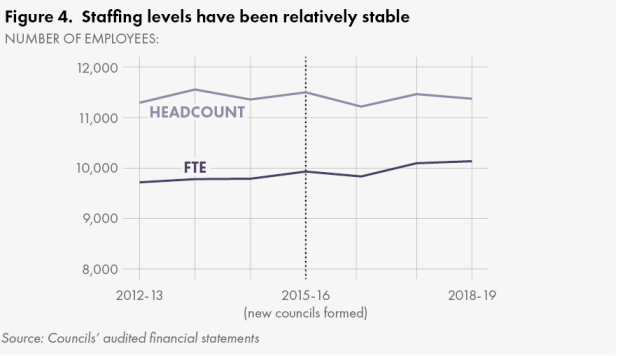

1.9 The total number of Full Time Equivalent (FTE) employees remained relatively stable in 2018-19. The total number of FTE employees across all councils has increased since their formation in 2015 (see Figure 4). This is a result of the net effect of planning staff transfers from central government to councils in 2015 (as well as the transfer of other functions) and recruitment, offset to an extent by council staff leaving on exit packages and natural wastage. As councils are not required to report the number of agency staff contracted during the year, the actual total workforce at each council is likely to be higher than reported.

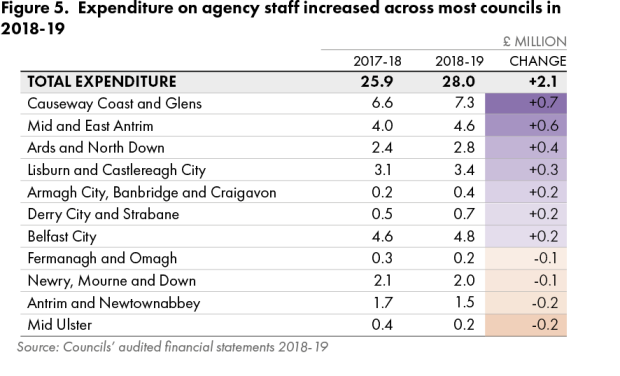

1.10 In 2018-19, total employee costs represented approximately 39 per cent (£381 million) of total operating expenditure, with agency staff accounting for a further 3 per cent (£28 million). The overall cost of agency staff has continued to increase year on year (£2.1 million increase in 2018-19) and agency staff costs vary significantly across councils (see Figure 5). Last year I reported that agency costs in the majority of councils had reduced or remained static. In comparison, in 2018-19 agency costs in seven councils have increased from the prior year. Most of this increase was attributable to Causeway Coast and Glens Borough Council, Mid and East Antrim Borough Council and Ards and North Down Borough Council.

Exit Packages

The number and cost of exit packages increased significantly in 2018-19

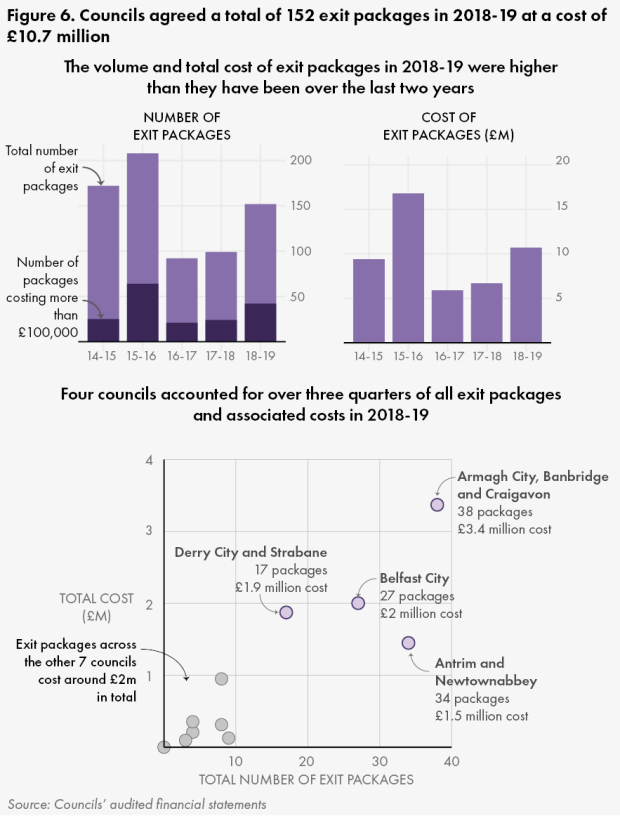

1.11 Councils are required to disclose the number and cost of staff exit packages. The costs include compulsory and voluntary redundancy costs, pension contributions and other departure costs. Over the five financial years from 2014-15 to 2018-19 councils have paid a total of £49.5 million in exit packages to staff (see Figure 6). The number and cost of exit packages has increased significantly in 2018-19, with councils agreeing 152 exit packages at a cost of £10.7 million (in 2017-18, 99 exit packages were agreed at a cost of £6.7 million). The majority of the exit package costs were in four councils.

Capital expenditure and financing

In 2018-19 total capital expenditure was £131 million, increasing for the first time since the formation of the new councils

1.12 Capital expenditure relates to assets which are purchased, constructed or improved by the councils, to support the delivery of their services. These range from one-off purchases in-year, to larger projects which can take more than one year to complete.

1.13 Councils finance capital expenditure in a number of ways including revenue funding, borrowing (from the government or commercial lenders), capital receipts, grants and other contributions. Councils are required to be prudent and consider the affordability of their capital expenditure programme and its impact on the day-to-day running of its services.

1.14 Capital expenditure in 2018-19 totalled £131 million (£101 million in 2017-18) and Figure 7 shows how this compares with real-term capital expenditure over the previous five years. It illustrates a significant increase in the year preceding council mergers and a peak in 2015-16, the first year of the new councils. Since then, capital expenditure levels have reduced, with the 2018-19 financial year seeing the first increase in capital expenditure since the councils merged.

1.15 A number of significant projects have contributed to the level of capital expenditure in 2018-19 including:

- Ards Blair Mayne Leisure Centre (Ards and North Down);

- South Lake Leisure Centre (Armagh City, Banbridge and Craigavon);

- Lisnasharragh Leisure Centre (Belfast);

- Andersonstown Leisure Centre (Belfast);

- Olympia Leisure Centre (Belfast);

- Brook Activity Centre (Belfast);

- Down Leisure Centre (Newry, Mourne and Down); and

- Portrush Public Realm and North Pier (Causeway Coast and Glens).

1.16 Councils’ total ‘Capital Financing Requirement’ increased from £655 million in 2017-18 to £713 million in 2018-19. This is a measure of a council’s underlying need to borrow to fund capital expenditure. The financing mix (using council reserves or obtaining loans) will be determined by each individual council, depending on its treasury management strategy and capital investment strategy. At 31 March 2019, councils had committed to ongoing or approved future capital schemes with an estimated cost of almost £343 million. A number of councils have highlighted the potential need for significant future external funding in order to complete their capital expenditure programmes.

Borrowing

Borrowing levels increased significantly for the first time since the formation of the new councils

1.17 Councils decide how much debt is required to deliver services. The costs of servicing the debt (repayment of principle amount and interest charges) should not adversely impact on service delivery.

1.18 The majority of debt relates to external borrowing which contributes to the financing of capital expenditure and consists of a mix of short-term and long-term loans, mostly from central government. Councils can also use overdrafts to assist with working capital balances.

1.19 Borrowing varies widely across councils and is based upon individual treasury management strategies and local priorities. It also reflects historical decision making, as the level of borrowing includes inherited loan balances from the legacy councils. Each council is required to maintain its long-term borrowing balance below the level of its Capital Financing Requirement. All councils complied with this requirement in 2018-19.

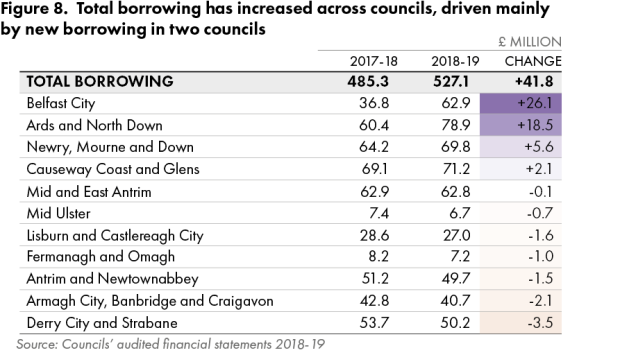

1.20 Loans outstanding at 31 March 2019 totalled £527.1 million, an increase of £41.8 million from 2017-18 (see Figure 8). This represents the first significant increase in borrowing since the formation of the new councils.

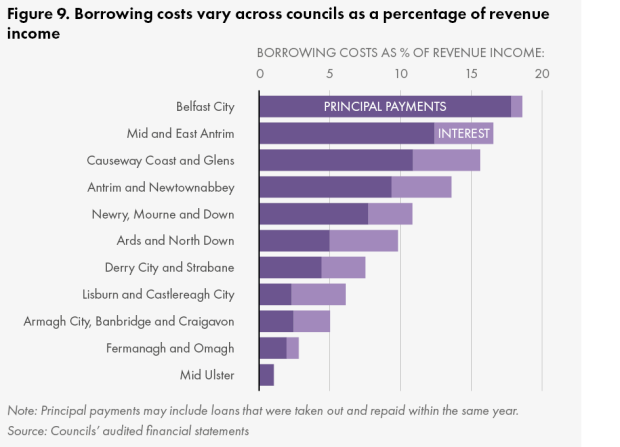

1.21 The annual costs committed to repaying loans reduces the amount councils have available to spend each year on delivering services (see Figure 9). The amounts paid during the year, and the extent to which this impacts services, depend on the period over which councils agree to repay their loans, as well as any impact from interest rate fluctuations and future inflation. In 2018-19, councils paid almost £78 million towards the principal outstanding balances and over £٢٣ million in interest costs.

Pensions

Pension liabilities are a significant cost pressure and the net pension liability increased to £549 million

1.22 The vast majority of council pension liabilities are the responsibility of the Northern Ireland Local Government Officers Superannuation Committee, which operates a pension scheme fund for the local councils and other similar bodies in Northern Ireland. In 2018-19, councils’ total net pension liabilities increased by almost 10 per cent, to £549 million. The pension liability increased across all councils.

1.23 Council pension liabilities have been impacted by the outcomes in recent legal cases. In December 2018, the Court of Appeal ruled that transitional arrangements put in place when firefighters’ and judges’ pension schemes were reformed were age discriminatory. Whilst the judgement was not in relation to members with Local Government Pension Scheme (NI) benefits, it is reasonable to assume that the Government will seek remedy for all public sector schemes and so all 11 councils were required to increase their pension liability. The impact of this, along with adjustments required to address historic inequalities that arose due to the existence of Guaranteed Minimum Pensions, was an increase of £53 million in the total council pension liability in 2018-19.

1.24 Pension contributions have been a cost pressure for councils in recent years. Every three years an independent review is undertaken to calculate how much each council should contribute. Councils contribute a percentage rate plus deficit recovery contributions. The percentage contribution rate in 2018-19 was 19 per cent of employees’ gross salary and will increase by 1 per cent each year until 2021, when a new review will set new contribution rates.

Reserves and investments

Whilst overall levels of usable reserves have increased since the formation of the new councils, some General Fund balances have declined rapidly

1.25 All councils hold invested funds, the majority of which are liquid cash reserves which generate small amounts of interest-based income. Other forms of long-term investment portfolios can include commercial property rental, and investments in associated companies, charities and trust funds, however, these type of investments are uncommon in Northern Ireland.

1.26 Usable reserves play an important role in councils’ financial management. The main usable reserves are the General Fund (£109 million), Capital Reserves (£93 million) and the Renewal and Repairs Fund (£15 million). These reserves can be used to finance major projects or to respond to unexpected events, however they need to be managed carefully.

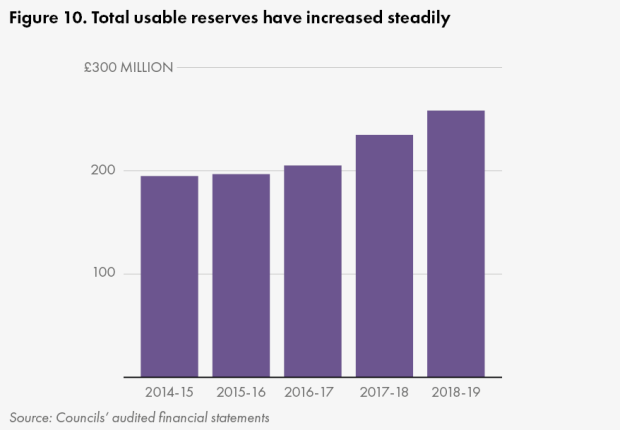

1.27 Figure 10 shows that the overall level of usable reserves across councils increased by 9.7 per cent, from £235 million in 2017-18 to £258 million in 2018-19. Prior to 2017-18 the total value of usable reserves had remained relatively constant. All but three councils increased their level of usable reserves during 2018-19.

1.28 The General Fund is the main usable reserve and accounts for over 40 per cent of the total usable reserves. It represents the surplus of income over expenditure. It can be used to provide for any unexpected expenditure that cannot be managed within existing budgets, or to supplement income where necessary. Each council should set its General Fund at a prudent but not excessive level, as holding a high level of reserves can impact on resources and performance.

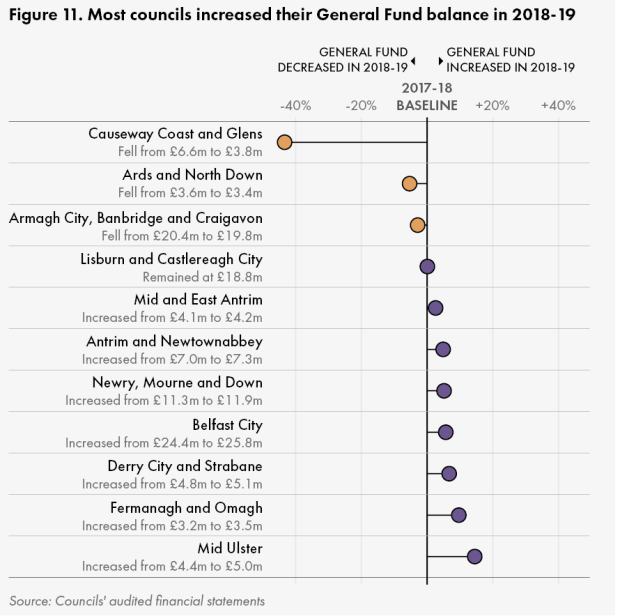

1.29 Overall, the total General Fund balance held by all councils remained relatively static during 2018-19 at £108.6 million. During 2018-19 seven councils increased their General Fund balance while others needed to use the fund to supplement income to enable continued service delivery. In one council the General Fund balance decreased by more than 40 per cent (see Figure 11).

1.30 I previously observed the need for councils to keep their reserves policy under review and ensure that sufficient, but not excessive reserves were retained to meet the challenges ahead. Whilst most councils have been able to achieve this despite increasing financial pressures, one council’s General Fund reserve decreased significantly and this must be closely monitored. In the current economic climate, where council income has been significantly reduced as a result of the Covid-19 crisis, it is very likely that councils may need to utilise their reserves in order to continue to deliver local services.

Observation

Councils should ensure that reserve balances are monitored and managed closely, particularly as income levels decline as a result of the Covid-19 crisis. In the longer term, councils should consider the reasons for the level of reserves held and ensure they are used for the purposes intended.

Financial Management

Councils face significant financial challenges, which require robust financial management arrangements to ensure long-term financial sustainability

1.31 Councils are facing significant financial challenges including the impact of central government budgeting decisions, the need to identify significant efficiency savings and service transformation to be able to fund local services without significant rate increases. The impact of the Covid-19 pandemic, which has led to a significant reduction in income and increased expenditure, increases the scale of the financial challenge facing councils. Robust financial management will be essential to achieving financial sustainability.

1.32 The CIPFA Financial Management Code (the FM Code), published in October 2019, is designed to support good practice in financial management and to assist local authorities in demonstrating their financial sustainability. The FM Code identifies risks to financial sustainability and introduces an overarching framework of assurance which builds on existing best practice and sets explicit standards of financial management.

1.33 The FM Code is based on a series of principles supported by specific standards and statements of practice which are considered necessary to provide the strong foundation to:

- financially manage the short, medium and long-term finances of a local authority;

- manage financial resilience to meet foreseen demands on services; and

- financially manage unexpected shocks in their financial circumstances.

1.34 The underlying principles that inform the FM Code include:

- Leadership demonstrating a clear strategic direction based on a vision in which financial management is embedded into organisational culture.

- Accountability based on medium-term financial planning that drives the annual budget process.

- Transparency is at the core of financial management, using consistent, meaningful and understandable data, reported frequently with evidence of periodic officer review and elected member decision-making.

- Long-term sustainability of local services is at the heart of all financial management processes and is evidenced by prudent use of public resources.

Conclusion

1.35 Councils are facing significant challenges in respect of financial sustainability and the pressure to maintain service levels with reducing resources. Robust financial management arrangements will be essential to aid decision-making and ensure the most efficient and appropriate use of resources.

Part Two: Good Governance

Key messages

- Councils’ governance statements complied with relevant guidance and continue to be comprehensive and of good quality.

- Audit and Risk Committees should continue to assess their effectiveness and ensure they exhibit the key effective characteristics expected from them.

- Councils should ensure that Internal Audit has sufficient resources to complete its planned work.

- All councils should report actual, suspected and attempted frauds to the Local Government Auditor.

- Concerns continue to be raised directly with the Local Government Auditor primarily in relation to planning processes.

Proper arrangements to secure economy, efficiency and effectiveness

Each council had in place proper arrangements to ensure economy, efficiency and effectiveness in the use of resources

2.1 The Local Government (Northern Ireland) Order 2005 requires me to be satisfied each year that proper arrangements have been made for securing economy, efficiency and effectiveness (value for money) in the use of resources. Details of the nature of my work in this area are outlined in Chapter 3 of my Code of Audit Practice 2016. In order to assess whether proper arrangements are in place, my staff require councils to complete an annual questionnaire and provide supporting documentation on a wide range of corporate activities including financial planning and reporting, IT security, procurement policy and procedures, risk management and governance arrangements.

2.2 As a result of my audit work in this area, I was satisfied that all 11 councils had in place proper arrangements to ensure economy, efficiency and effectiveness in the use of resources for the 2018-19 financial year. No public interest reports were made during the year and my audit findings were issued to each council in their annual audit letter.

Governance Statements

Governance statements continue to be comprehensive and of good quality

2.3 The annual governance statement accompanies a council’s financial statements and explains its governance arrangements and controls for managing the risk of failing to achieve strategic objectives. It is a key statement by which a council demonstrates to its ratepayers, elected members and other external stakeholders that it is complying with the basic tenets of good governance.

2.4 The statement explains the process for reviewing the effectiveness of those arrangements, and outlines actions taken to deal with any significant governance issues. What is considered significant will depend on an individual council’s governance framework, how effectively it is operating and the extent to which the issue has the potential to prevent a council from achieving its strategic objectives. The number of individual significant issues raised varied considerably between councils, ranging from zero to seven. This may be wholly reasonable, however, councils must be content that this reflects the results of robust management and review of their governance framework.

2.5 As with the previous year, I have found the governance statements to be comprehensive and of good quality.

There were a number of common significant issues disclosed within governance statements, as well as a number of common issues arising from my audits

2.6 Many of the more common significant governance issues identified by councils in their 2017-18 governance statements featured again in 2018-19 including: budgetary uncertainty; meeting waste management targets; ICT security and the ongoing uncertainty of leaving the European Union (see Part Four, paragraph 4.22). Other issues included Local Growth/City Deals (see Part Four, paragraphs 4.14 to 4.21), and procurement and contract management.

2.7 During the audit of the 2018-19 financial statements I raised a number of audit issues and made recommendations for improvement. These included procurement and contract management issues and significant expenditure on agency staff (see Part One). I will monitor councils’ implementation of these recommendations in future audits.

2.8 In my report on Derry City and Strabane District Council, I included an emphasis of matter paragraph, drawing attention to disclosures included in the Council’s financial statements of the potential impact on the carrying value of assets connected with City of Derry Airport. The key concern is the uncertainty in respect of sufficient funding for the London airport route. Should these going concern issues crystallise, then there may be a significant impairment on the carrying value of airport assets (£45 million as at 31 March 2019). The Council told me that it completed a tender exercise in 2019, appointing an operator for the London route from September 2019 to March 2021. Council officers are now completing a funding proposition for 2021 to 2026.

Audit and Risk Committees

Audit and Risk Committees should continue to assess their effectiveness and ensure they exhibit the key effective characteristics expected

2.9 The main purpose of an Audit and Risk Committee is to give independent assurance to elected members and the public about the governance, financial reporting and financial management of a council. It also scrutinises the council’s financial management and reporting arrangements and provides an independent challenge to the council. All councils have Audit and Risk Committees in place and my staff attend meetings of these committees on a regular basis.

2.10 In 2018, the Chartered Institute of Public Finance and Accountancy (CIPFA) emphasised the impact that an effective audit committee can have. It is my opinion that the mechanisms and procedures to facilitate the effectiveness of councils’ Audit and Risk Committees continued to improve during the year. I encourage all Audit and Risk Committees to continue to assess their effectiveness and also to ensure that they are satisfied with the quality, relevance and timeliness of information and data submitted to them.

Internal Audit

A professional, independent and objective Internal Audit service is one of the key elements of good governance

2.11 The Public Sector Internal Auditing Standards (PSIAS), which came into force in April 2013 and were updated in April 2017, are applicable to all public sector bodies in the UK. The PSIAS includes a definition of internal auditing and provide detail on the main areas where Internal Audit activity must contribute to improvement including governance, risk management and internal control.

2.12 The PSIAS apply to all Internal Audit providers, whether in-house, shared services or outsourced. A number of Internal Audit functions did not complete all of the work planned during 2018-19, and were required to roll forward work into 2019-20. In most cases this was due to resourcing issues. The core principles of the PSIAS require that Internal Audit services are “appropriately positioned and adequately resourced” therefore councils should ensure that Internal Audit has sufficient resources to fulfil its planned work. It is also important to highlight that Internal Audit must remain independent and, as such, councils should ensure that Internal Audit is not asked to take on any duties which could impact on its independence.

Code of Conduct

The Northern Ireland Local Government Commissioner for Standards considers complaints where a Councillor may have failed to comply with the Northern Ireland Local Government Code of Conduct for Councillors

2.13 Councillors are expected to observe the highest standards of behaviour in undertaking their official duties. They are required to comply with the principles and rules of conduct set out in the mandatory Code of Conduct for Councillors (the Code), introduced in May 2014.

2.14 The Code is based on 12 principles of conduct which are: Public Duty, Selflessness, Integrity, Objectivity, Accountability, Openness, Honesty, Leadership, Equality, Promoting Good Relations, Respect, and Good Working Relationships.

2.15 Each council is required to establish, maintain and make publically available a register of members’ interests. Also, the Code recommends that a register for gifts and hospitality is established and that procedures are in place for dealing with relevant declarations of interests.

2.16 The Northern Ireland Public Services Ombudsman (the Ombudsman), in their role as Northern Ireland Local Government Commissioner for Standards (the Commissioner), is responsible for investigating and adjudicating on complaints that a councillor has failed to comply with the Code.

2.17 In order to maintain an appropriate separation of the investigative and adjudication functions, the Commissioner has delegated the authority to conduct investigations and report on the outcome of investigations to the Deputy Commissioner and his staff in the Local Government Ethical Standards Directorate.

2.18 In addition to, or as an alternative to investigating a complaint, the Deputy Commissioner can also take alternative action to resolve a complaint, for example by requiring a councillor to apologise for his or her conduct or to attend training on the Code.

2.19 If the Commissioner adjudicates on a case and finds that a councillor has failed to comply, they can impose a sanction that, in the most serious cases, can result in disqualification from serving as a councillor for a period of up to five years.

2.20 In December 2018, an updated formal protocol was signed with the Ombudsman which sets out arrangements for co-operating and working together, both in the role as Ombudsman and as Commissioner, in order to fulfil our statutory responsibilities as fully, effectively and efficiently as possible.

2.21 Each year, the Commissioner receives a number of complaints of failure to comply with the Code. The Commissioner’s Annual Report reveals that in 2018-19 a total of 62 complaints were made against councillors, compared to 44 in 2017-18. Around half of the complaints made were about councillors’ behaviour towards other people, including a failure to show respect and consideration. A third of complaints related to obligations as a councillor. The Code requires councillors to act lawfully, in accordance with the Code, and not to act in a manner which could bring their position as a councillor, or their council, into disrepute. Where there are any financial implications arising from non-compliance with the Code, I may decide to report this information. I am not aware of any cases which have had financial implications this year.

Reporting fraud

Councils should continue to notify the Local Government Auditor of all actual, suspected and attempted frauds

2.22 Local councils agreed to voluntarily submit returns about all actual, suspected and attempted frauds involving public money to the Local Government Auditor from 1 April 2016. This mirrors the requirement for all central government bodies, including core departments, agencies, non-departmental public bodies and other sponsored bodies, to report all actual, suspected and attempted frauds to the C&AG, under the terms of Managing Public Money (NI).

2.23 Fraud reporting plays an important part in identifying potential control weaknesses and highlighting areas where controls need to be introduced, amended or strengthened. It allows me to have an overview of risks across the sector and can help to highlight the need for fraud alerts or additional guidance, as part of the continuing fight against fraud.

2.24 The NIAO guide on Covid-19 Fraud Risks was published in September 2020. This short guide highlights key risks, sets out controls that can mitigate those risks and provides details of further sources of guidance for NI public sector organisations.

Raising concerns

The majority of concerns raised continue to relate to the planning process

2.25 Effective arrangements for raising concerns are an important element of good governance arrangements and are essential for helping to bring to light matters of concern in an organisation. Where wrongdoing exists, those responsible must be held to account, mistakes must be remedied and lessons must be learnt.

2.26 All councils may receive concerns in line with their own policies. Councils must have procedures in place to deal promptly and robustly with concerns raised and must ensure that those raising concerns are supported and protected from any form of detriment or victimisation.

2.27 As the Local Government Auditor within the NIAO, I am a prescribed person to whom protected disclosures can be made, under the Public Interest Disclosure (NI) Order 1998, in relation to the proper conduct of public business, fraud and corruption and value for money. In that capacity, I receive concerns relating to local government bodies (see Figure 12).

Figure 12. Concerns reported directly to the Local Government Auditor

|

2015-16 |

2016-17 |

2017-18 |

2018-19 |

2019-20 |

|

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

Number of concerns reported directly to the LGA |

12 |

15 |

23 |

23 |

18 |

Source: NIAO data

2.28 In June 2020 the NIAO published a good practice guide on raising concerns. The guide encourages organisations to put in place effective arrangements for receiving concerns from the wider public and ensuring that they are properly considered and appropriately acted upon. The guide also suggests organisations appoint a speak-up guardian or raising concerns champion who can be a source of advice and support for staff and a key resource for connecting the organisation to service users and the wider public.

2.29 The NIAO website provides contact details for those wishing to raise a concern with me as the Local Government Auditor. Concerns raised will be evaluated as audit evidence, taking into account a range of factors including:

- professional judgment;

- audit experience;

- whether there is a “public interest” element to the issue; and

- whether the concerns indicate serious impropriety, irregularity or value for money issues.

2.30 I consider a number of possible actions when dealing with concerns. These range from discussing the issues with the audited body, to carrying out a full audit investigation and including relevant comments in our audit reports. I am not required to undertake investigations on behalf of individuals.

2.31 I note that concerns about the planning process continue to be the most commonly raised with me. I would urge councils to ensure consistency in the approval, or rejection, of planning applications, as well as the retention of documentation to support the rationale for planning decisions.

2.32 Adhering to good practice and ensuring lessons are learned from previous planning processes, as well as from other UK regions, is essential. In collaboration with the C&AG, I have now commenced a study on Planning in both central and local government.

Conclusion

2.33 All councils have made positive progress in strengthening their governance arrangements since their formation in 2015, particularly around the adoption of good practice to promote more effective Audit and Risk Committees. However, I would encourage all councils to notify me of all actual, suspected and attempted frauds.

Part Three: Performance Improvement

Key Messages

- All councils strengthened their performance improvement arrangements and each council demonstrated measurable improvements to functions.

- Due to the impact of the Covid-19 pandemic, the requirement to publish annual performance plans for 2020-21 by 30 June 2020 was set aside. Self-assessment reports, outlining councils’ performance against their 2019-20 performance improvement plans, were still required to be published by 30 September 2020. Due to the ongoing impact of Covid-19 the Department is consulting with councils on performance improvement requirements over the next two years.

- The first statements of progress for each community plan were published by each council in November 2019 and highlight some promising initiatives.

- The first results of the Planning Monitoring Framework were published in September 2019 by the Department for Infrastructure, showing significant variations in performance between councils.

Performance Improvement audits and assessments

Councils have a statutory responsibility to make arrangements for, and report on, continuous improvement in functions or services

3.1 The performance improvement framework has been phased in since 2015-16 and became fully operational in 2017-18. It places a statutory responsibility on councils to make arrangements for, and report on, continuous improvement in their functions or services. Improvement should be more than gains in service output or efficiency, or the internal effectiveness of an organisation. The activity should enhance the sustainable quality of life and environment for ratepayers and communities. The framework also places a statutory responsibility on me to conduct an ‘improvement audit and assessment’ each year and report my findings.

3.2 Councils are required to select and consult on improvement objectives and then publish these in annual performance improvement plans, along with details of how they plan to achieve them. Underlying this, councils are required to make arrangements to deliver each objective and collect data to enable them to report on the achievement of improvements. Councils had to publish details of this information for 2018-19 in their annual self-assessment report in September 2019. This report considered their performance against the objectives they had set. It also reported performance against planning, waste management and economic development standards and indicators set by central government, and made comparisons with other councils.

3.3 I am required to assess and report whether each council:

- discharged its duties in relation to improvement planning;

- published the required improvement information;

- acted in accordance with guidance issued by the Department in relation to those duties; and,

- was likely to comply with legislative requirements for performance improvement.

3.4 My detailed findings in respect of the 2019-20 plans and the 2018-19 performance reports were reported to each council and the Department in November 2019. I subsequently published summaries of my findings for each council on the NIAO website in March 2020. I did not undertake any special inspections or recommend formal intervention by the Department.

Councils strengthened their performance improvement arrangements in year

3.5 All of the councils met their key performance improvement responsibilities for publishing performance improvement plans and self-assessment reports during the year. Although councils are at different stages of development, all strengthened their performance improvement arrangements and each council demonstrated measurable improvements to functions. In September 2019, NIAO published a good practice briefing which identifies some key aspects of improving performance, illustrated by examples drawn from councils’ experience.

3.6 Given the track record of performance improvement achievements now available, for the first time I was able to undertake an assessment of whether the councils were likely to meet their performance improvement responsibilities under legislation for the remainder of the 2019-20 year. For all but one council I concluded that they were likely to comply with these responsibilities. For Causeway Coast and Glens Borough Council, it was not possible for me to assess if its performance improvement arrangements were sufficiently developed to deliver measurable improvements, and whilst there were some indications of improvement, the embedding of performance management systems and council structures are essential to resolving this going forward. I therefore concluded that the Council was unlikely to comply with its legislative performance improvement responsibilities during 2019-20.

3.7 Councils have a wide degree of discretion on their performance improvement arrangements within the overall statutory framework. As a result, my audit work in 2019-20 continued to focus primarily on compliance with the legislation and guidance; and on identifying and sharing emerging good practice. I have provided feedback to each council on how its arrangements could be further improved. However, it is a matter for each council to decide the extent to which it accepts my proposals. I reviewed what progress had been made on implementing my previous proposals on performance improvement. Generally councils had resolved many of the issues that I had raised, however in some instances I recommended that addressing these issues needed to be given more priority.

3.8 In previous years I identified challenges that some councils faced in collecting data to support any claims of improvement. Much progress has been made in establishing management information systems and improving the measurements used to assess improvement, but in some instances further work is needed to fully resolve the issues. Whilst some councils had undertaken data validation exercises to gain assurance on the accuracy of the underlying information being used to monitor and assess performance, others needed to develop this further. I also noted instances where inaccurate performance information had been published by councils.

3.9 Generally, improvement objectives for 2019-20 are focussed, realistic and achievable. However there are still some instances of objectives being strategic in nature and this can make it challenging for councils to demonstrate that improvements are achieved. In some cases defined measures of success, indicating quantifiable targets, together with baseline information would assist councils in being able to better demonstrate the achievement of an objective. Whilst some councils may find it difficult to realise more aspirational objectives, the arrangements made to deliver these objectives may nonetheless result in some demonstrable improvements.

3.10 This was the third year that councils were required to report on their performance against that of other councils in delivering the same or similar functions, where it was reasonably practicable to do so. Whilst comparisons had been made in prior years on statutory indicators set by central government on planning, waste management and economic development, comparisons relating to self-imposed indicators were very limited. During 2019 the Department advised that comparisons should be published in the 2018-19 self-assessment reports on at least two self-imposed indicators for prompt payment and sickness absence, relating to the ‘General Duty’ to improve. However I noted in my reports that significant progress by all councils was needed to allow a broader range of functions to be benchmarked in future. A sub-group of SOLACE’s performance improvement working group prepared a paper on the way forward to establishing a regional performance framework for benchmarking during 2019, but a considerable amount of work would be necessary to take this forward.

3.11 Last year I noted the progress made on clarifying the requirements of the ‘General Duty’ to improve within the Department’s statutory guidance by the multi-stakeholder group, which included representatives from the Department and councils. This resulted in new guidance on the General Duty being issued by the Department in June 2019 and this has resolved many of the issues raised in previous performance improvement audits in this area.

Impact Covid-19 may have on performance improvement arrangements over the next two years

3.12 During 2020 the Covid-19 pandemic impacted significantly on the delivery of council services and on councils’ ability to publish annual performance plans for 2020-21 by 30 June 2020. The Department therefore set aside this requirement for 2020-21 but indicated that self-assessment reports, outlining councils’ performance against their 2019-20 performance improvement plans, should still be published by 30 September 2020. Given the ongoing impact of Covid-19 the Department is consulting with councils on performance improvement requirements over the next two years. It has initially suggested that it may be more beneficial for councils to produce plans setting out their proposals for service delivery and performance recovery, rather than the performance improvement plans currently required by legislation and statutory guidance. I look forward to discussing the audit arrangements for this work with the Department in the coming months.

Community Planning

Councils published their first statements of progress on Community Planning in November 2019 highlighting progress on a range of projects

3.13 Community planning is a new responsibility for councils, designed to improve the lives and wellbeing of residents throughout the council’s area. It involves working with a wide range of partners, including the community and voluntary sector, education, health, Police Service of Northern Ireland and Tourism Northern Ireland. As lead partner of each of the 11 Community Planning Partnerships, each council published its first ‘Community Plan’ between March and November 2017, setting out community visions, ambitions and goals for each council area to improve the social, economic and environmental wellbeing of districts and the people who live there.

3.14 The Local Government Act (Northern Ireland) 2014 requires councils to publish a statement on outcomes achieved and actions taken within two years of the plan being published. Community planning partners must provide the council with relevant information to enable them to prepare this statement. In addition, councils must carry out a review of the plan before its fourth anniversary.

3.15 In December 2018 the Department issued guidance to Community Planning Partnerships and Statutory Community Planning Partners to provide practical advice on the arrangements for monitoring and reporting on community plan progress. The first statement of progress for each community plan was published in November 2019, with councils reporting progress against outcomes to date and highlighting projects which have begun to make a difference to local communities.

3.16 Councils have adopted a variety of formats for their progress reports, from short summary documents, to extensive reports covering more than 100 pages. The content of the reports also varies widely. Most councils have used a form of Red/Amber/Green (RAG) rating to report progress against each outcome or action. Some councils have also used a balanced scorecard approach to assess each action and have put action plans or priorities in place.

3.17 Varying levels of progress have been reported by councils over the first two years of their community plans. Whilst some reported that the majority of indicators showed a positive change, this was often not quantified. Some councils considered that it was too early in the process to determine whether progress had been made, or stated that there was not enough data available to measure progress, while others were able to demonstrate some progress including the number of jobs created, a reduction in the volume of waste going to landfill, and the extent of new social housing built.

3.18 A number of projects that have commenced as part of the community plans have the potential to make a difference in local communities. Most councils have used case studies to illustrate the type of project being delivered and demonstrate the potential to make a difference in local communities. There are some common themes amongst the projects including dementia friendly events, ageing well initiatives, jobs and careers fairs, multi-agency support hubs and active community events.

3.19 Although an audit of community plans is not required, I assessed and reported on whether councils’ improvement objectives in their 2018-19 Performance Improvement Plans had links to community planning, as part of the improvement audit and assessment. I am pleased to note that all councils demonstrated the necessary links. I welcome the ongoing engagement and support that the Department has with Community Planning Partnerships, and encourage all partners, both statutory and non-statutory, to fully engage in and support this process.

Planning: the Planning Monitoring Framework

The first results of the Planning Monitoring Framework were published in September 2019 and show significant variations in performance against planning targets

3.20 As noted in paragraph 3.2, part of my audit and assessment of councils’ arrangements for continuous improvement includes their performance against statutory planning standards and indicators.

3.21 Recognising that the standards and indicators relating to planning do not cover all the planning work undertaken by councils, the Department for Infrastructure introduced, from 1 April 2018, a further set of performance indicators covering wider planning activity. By measuring and reporting on progress against these indicators, councils are able to evidence and demonstrate their contribution towards the draft Programme for Government outcomes and their stated purpose of improving wellbeing for all, by tackling disadvantage and driving economic growth. The indicators also allow councils to report their progress in implementing their community plans and the associated local development plans.

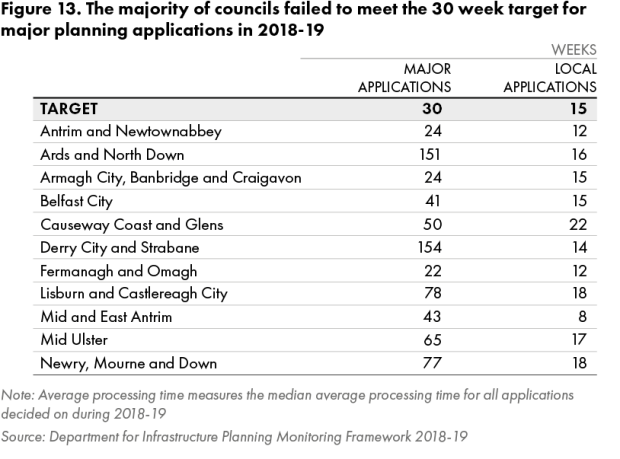

3.22 Data was collected from 1 April 2018 and the first results were published, along with the Department for Infrastructure’s 2018-19 official planning statistics, in September 2019. The results demonstrate that there are significant variations in performance against planning targets amongst the 11 councils (see Figure 13). For example, the time taken to process major planning applications ranged from 22 to 154 weeks and only 3 of the 11 councils were able to meet the 30 week target for major applications. Performance against the 15 week target for local applications ranged from 8 to 22 weeks. As previously noted, in collaboration with the C&AG, I have now commenced a detailed study on the Planning process in both central and local government. This will include an assessment of councils’ performance against statutory targets.

Conclusions

3.23 Councils continue to strengthen their performance improvement arrangements and I have continued to provide feedback on areas which could be strengthened. I will continue to discuss the way forward for the performance improvement arrangements with the councils and the Department in the months ahead.

3.24 The first results of the Planning Monitoring Framework highlight that whilst there are significant variations in performance against planning targets across the 11 councils, the majority consistently miss the statutory target for approving major applications. These issues will be explored in more detail as part of the study on the planning process in both central and local government.

Part Four: Challenges and Opportunities

Key messages

- The Department for Communities has not yet completed the planned review of the Local Government Reform Programme.

- Levels of staff absenteeism continue to represent a challenge for councils.

- Prompt payment of suppliers varies significantly across councils.

- Economic Growth Deals now cover the whole of Northern Ireland and represent considerable opportunities for councils.

- The continued response to the Covid-19 pandemic presents a significant challenge to all councils.

Efficiency Savings

The Departmental review of the Local Government Reform Programme has been delayed

4.1 In my 2018 report, I recommended that the Department should give early consideration to, and clear guidance to councils on, devising an appropriate methodology for measuring efficiency savings and reporting outcomes relating to the reduction in the number of councils in 2015.

4.2 Last year, I reported that the Department would carry out a review of the cost benefit analysis of local government reform for the period 1 April 2015 to 31 March 2019, analysing monetary and non-monetary factors. The Department intended to complete this review during 2019-20, however it has been delayed and will now be completed during 2020-21.

4.3 Further delays in completing this review should be avoided. I will continue to monitor and engage with the Department in relation to this project and may decide to report on this matter in more detail in the future.

Absenteeism

Overall sickness absence rates remained high, with an average of almost 14 days lost per employee

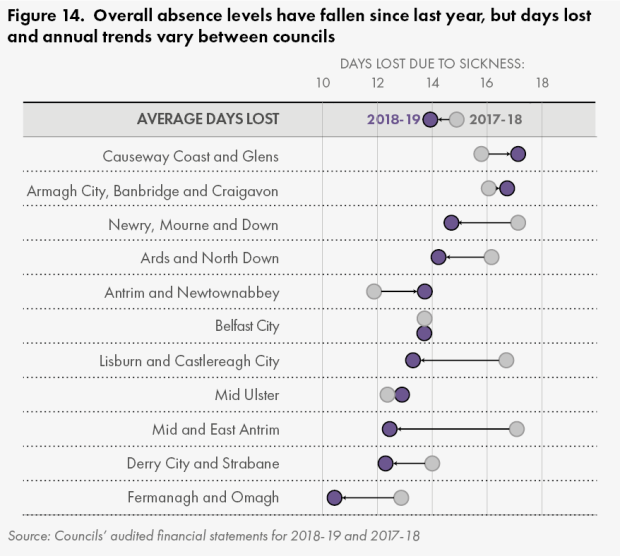

4.4 Whilst there was a small decrease in absence rates in 2018-19, overall absence rates remain high and there has been very little improvement over the years. In 2018-19, the average sickness absence rate for the councils was 13.9 days (14.9 days in 2017-18) representing approximately 6.4 per cent of total working days (see Figure 14).

4.5 The data for 2018-19 continues to show a significant range in the average number of days lost per employee. Fermanagh and Omagh District Council recorded the lowest number of days lost at 10.4 days (12.9 days in 2018-19), while Causeway Coast and Glens Borough Council recorded the highest rate at 17.1 days (15.8 days in 2017-18). In seven councils, absence levels have reduced since the previous year, with increases in the other four.

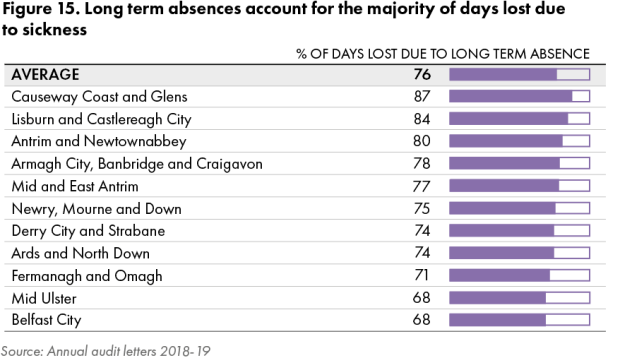

4.6 The majority of days lost at each council relate to long-term absenteeism (average of 10.6 days in 2018-19), with conditions such as musculoskeletal problems, stress and depression being key contributors (see Figure 15).

4.7 I have consistently highlighted the importance of closely monitoring and actively managing sickness absence levels. This is to ensure that staff welfare is protected and that the delivery of front line services is not adversely affected. A detailed report on ‘Managing attendance in central and local government’ was published in November 2020. The report highlights good practice, and provides additional guidance on managing attendance.

Prompt Payment

The majority of councils fail to meet prompt payment targets for their suppliers

4.8 Councils are encouraged to pay suppliers as promptly as possible and to endeavour to meet the commitment made by the Northern Ireland Executive to pay the majority of valid invoices within 10 days. The average number of days taken to pay a supplier varies considerably across the councils.

4.9 In 2018-19, six councils paid at least half of their valid invoices within 10 days. Whilst this is an improvement on the prior year, when five councils managed to achieve this, most councils’ performance still falls significantly behind central government performance (see Figure 16).

Observation

As in previous years, the prompt payment statistics show there is considerable room for improvement across most councils. Prompt payment of invoices helps businesses’ cashflow and this is increasingly important in order to maintain financial viability in the current challenging economic climate.

Asset management

Good asset management is essential to help deliver sustainable public services

4.10 In Part One of this report (paragraphs 1.12 to 1.16) I highlighted the significance of capital expenditure, which relates to the purchase and improvement of council assets. Councils own and manage a significant number and range of public assets which are used to support the delivery of their services. The value of these assets at 31 March 2019 was in excess of £2.5 billion, with a small proportion (with an approximate value of £27 million) currently surplus to requirements, or being held for future development.

4.11 There is increasing pressure, since the formation of the 11 councils in 2015, to consolidate, replace and maintain ageing public sector assets, as well as manage the risks associated with operating ageing assets. This is set against a backdrop of increasing resource pressures. It is therefore essential that councils ensure their asset management practices are sufficient to help deliver sustainable public services. In my 2019 report I included nine principles of good asset management. In partnership with the Strategic Investment Board, work has commenced on a good practice guide on asset management.

Capital projects

Councils have announced ambitious capital expenditure plans which will require significant external funding

4.12 Councils are committed to spending almost £343 million on future capital projects, which include plans for leisure centres, play parks, civic buildings, community centres and village renewal schemes. However only £33 million of the required funding for these projects had been secured in grant-in-aid by 31 March 2019. Councils will need to identify sources of funding for these projects. It has been suggested that savings from service transformation, along with reserves and funding linked to City Deals, will be used, however these have not been quantified. It is probable that councils will require significant funding from external sources such as loans in order to proceed with these ambitious capital plans.

4.13 Some councils already have a significant amount of underlying debt (see paragraphs 1.17 to 1.21), and so the impact of any additional loan commitments needs to be considered carefully, in light of councils’ ability to meet repayments, the impact on cash available for service delivery and the effect on councils’ net debt position. Given the ongoing financial challenges arising from the Covid-19 pandemic, councils may need to reconsider future plans and commitments.

City Region and Local Growth Deals

Every part of Northern Ireland is now covered by an economic Growth Deal

4.14 Councils are partners in the City Region and Growth Deals. A total of £1.2 billion has been committed to date to support economic growth and development by promoting a range of measures and projects designed to increase the skills, productivity and competitiveness of each region. Four deals have now been agreed covering all 11 council areas:

- Belfast Region City Deal - £850 million

- Derry City and Strabane Region City Deal - £210 million

- Mid, South and West Growth Deal - £252 million

- Causeway Coast & Glens Growth Deal - £72 million.

Belfast Region City Deal

4.15 In its 2018 Autumn budget (the Budget), the UK Government committed £350 million of funding to the Belfast Region City Deal (BRCD). In May 2020, the NI Executive committed to match the £350 million of UK Government funding, with six participating councils committing £100 million and the two Universities committing £50 million. This makes the deal worth at least £850 million before any funding is attracted from the private sector. The deal is a binding, long-term agreement aimed at boosting economic growth led by the city region over 10 to 15 years. It is intended that the funding will be used to deliver a programme of capital investments to support the region’s high growth ambitions, creating up to 20,000 new and better jobs. The BRCD partners, including Regional further education colleges, universities and local councils will deliver a complementary employability and skills programme to ensure that people gain the necessary skills to secure and deliver on the new and better paid jobs that will be created.

4.16 Belfast City Council is leading the BRCD, which will require effective collaboration with robust governance and accountability arrangements between councils, central government public bodies, and the UK Government. In March 2019, the Secretary of State, BRCD partners and the Northern Ireland Civil Service signed a Heads of Terms document, enabling full business plans to be prepared for the projects proposed.

Derry City and Strabane District Area Deal

4.17 In May 2019, the UK Government announced a £105 million City Deal and Economic Growth Funding Package for the Derry City and Strabane District Area Deal. The investment package announced comprises a £50 million City Deal and a £55 million Inclusive Future Fund which aim to boost the economic potential of the city region and to support a more prosperous, united community and stronger society. In May 2020 the NI Executive further confirmed match funding for both the City Deal and Inclusive Future Fund investment totalling £105 million bringing the total confirmed funding to £210 million. Along with anticipated funding from project partners of £40 million, this will bring the total investment in the North West to around £250 million.

4.18 The investment will comprise three new innovation centres of excellence; enhancing and maximising digital connectivity; two major city and town centre regeneration schemes; tourism and skills investment; and a new Entry Level Medical School for Northern Ireland to be located at the Ulster University Magee.

Two Local Growth Deals have been announced covering the Mid, South and West of Northern Ireland and the Causeway Coast and Glens

4.19 In October 2019 the UK Government announced that Northern Ireland regions would benefit from an additional £163 million of funding to support local economic growth, create jobs and invest in local projects. The 2020 Budget announced two new Local Growth Deals:

- £126 million for the Mid, South and West of Northern Ireland deal; and

- £36 million for the Causeway Coast and Glens deal.

In May 2020 the NI Executive announced match funding for both Growth Deals, bringing the total values to £252 million and £72 million respectively. The Executive also announced a £100 million complementary fund in relation to the City and Growth Deals and councils are awaiting information on this package of support.

These Growth Deals bring opportunities as well as risks which will need to be carefully managed by councils and partners

4.20 The capacity of councils and their development partners to deliver large scale projects against a challenging public sector backdrop represents a significant risk. Councils will need to strike a balance between maximising opportunities and carefully managing the risks at all stages of the projects they embark upon.

4.21 Councils will have to ensure that robust accountability and governance arrangements are put in place, as well as considering how the long-term success of economic Growth Deals will be measured, including how they have contributed to Programme for Government outcomes. This will be key to determining the extent of economic growth and the extent to which value for money has been delivered. These City and Local Growth Deals are now more important than ever as councils assist in rebuilding the economy.

Observation

In light of the future challenges and opportunities presented by the economic Growth Deals, the C&AG and I will continue to monitor the Deals as they progress.

Councils are considering their readiness for leaving the European Union

4.22 Much uncertainty remains regarding the impact of leaving the European Union for councils. Councils’ readiness for exiting the European Union is considered at the monthly SOLACE meetings to ensure that all councils are taking a proactive approach. Council officers are working with colleagues across the 11 councils to ensure that areas of risk are identified and appropriate measures are in place to manage these risks where possible.

Impact of the Covid-19 pandemic

4.23 Councils have faced unprecedented challenges related to Covid-19 which will continue as they deal with both the immediate and longer-term repercussions of the pandemic. There has been a significant financial impact related to decisions made by councils in order to maintain public safety, particularly during the emergency response to the pandemic. There is likely to be a long-term and ongoing impact on the economy and public sector finances, however the full extent is unknown at this stage.

4.24 In May 2020, the Minister for Communities in Northern Ireland announced that the Executive was allocating £20.3 million to councils to assist them with their financial pressures up to the end of June 2020 as a result of Covid-19. This funding was to allow councils to continue to provide essential services such as waste collection and disposal, provision of registration and cemetery services and to support those in need. An additional £40 million was announced in September 2020 to support the operation of all 11 councils. In October 2020, the Executive allocated a further £15 million to councils to ensure that they continued to positively contribute to the response to, and recovery from Covid-19.

4.25 Many staff were furloughed due to the restrictions on service provision. Whilst some services have resumed, continued restrictions will impact on the ability to fully resume service delivery and income streams, particularly those from leisure and tourism, will continue to be significantly impacted.

Conclusion

4.26 Looking ahead, councils face a wide range of challenges and opportunities. In these unprecedented times, continuing to deliver positive outcomes will require strong leadership, effective governance structures and continued engagement both internally and externally. This can be further enhanced through the development of effective partnership arrangements with other public bodies and local communities.