Abbreviations

AO Administrative Officer

BCS Business Consultancy Service

CAL Centre for Applied Learning

CGTP Central Government Transformation Programme

Covid-19 Coronavirus

CPD Construction and Procurement Delivery

CS Civil Service

DAERA Department of Agriculture, Environment and Rural Affairs

DCAL Department of Culture, Arts and Leisure

DE Department of Education

DEL Department for Employment and Learning

DETI Department of Enterprise, Trade and Investment

DfC Department for Communities

DfE Department for the Economy

DfI Department for Infrastructure

DFP Department of Finance and Personnel

DoE Department of the Environment

DoF Department of Finance

DoH Department of Health

DoJ Department of Justice

DP Deputy Principal

DRD Department for Regional Development

DWP Department for Work and Pensions

ESS Enterprise Shared Services

EU European Union

FDA Trade union for senior and middle management civil servants and public sector professionals formerly known as The Association of First Division Civil Servants

FSNI Forensic Science Northern Ireland

FTE Full Time Equivalent

GB Great Britain

HoCS Head of the Civil Service

HoP Head of Profession

HR Human Resources

ICT Information and Communication Technology

NAO National Audit Office

NIAO Northern Ireland Audit Office

NICS Northern Ireland Civil Service

NICSHR NICS Human Resources function

NICTS Northern Ireland Courts and Tribunal Service

NIPS Northern Ireland Prison Service

NIPSA Northern Ireland Public Service Alliance

NISRA Northern Ireland Statistics and Research Agency

OECD Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development

OHS Occupational Health Service

PfG Programme for Government

PPE Post Project Evaluation

PPS Public Prosecution Service

PRONI Public Record Office of Northern Ireland

PSSSP Public Sector Shared Services Programme

RHI Renewable Heat Incentive

SCS Senior Civil Service

SIB Strategic Investment Board

SO Staff Officer

SRO Senior Responsible Owner

TEO The Executive Office

UK United Kingdom

VES Voluntary Exit Scheme

WHO World Health Organisation

Key Facts

Over 22,000 Staff working in the nine Northern Ireland Civil Service (NICS) departments and their executive agencies at April 2019

3,900 Reduction in staff in the NICS workforce during the four year period to April 2019

Almost £920 million Staff costs for the nine NICS departments and their executive agencies in 2018-19

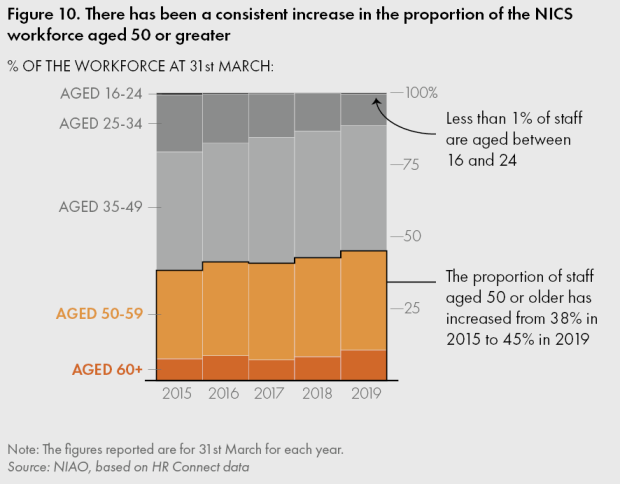

45% The percentage of the NICS workforce aged over 50 at March 2019

1,420 Staffing vacancies at March 2019 (6.9 per cent of the NICS workforce)

192% Increase in NICS temporary promotions between 2015 and 2019

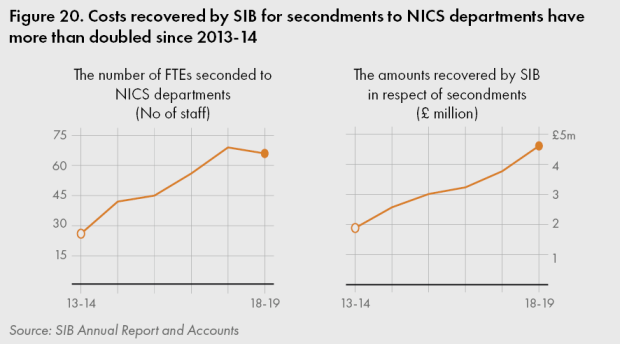

100% The percentage of NICS departments that had used the Strategic Investment Board (SIB) to address skills gaps over the three years to 2018-19

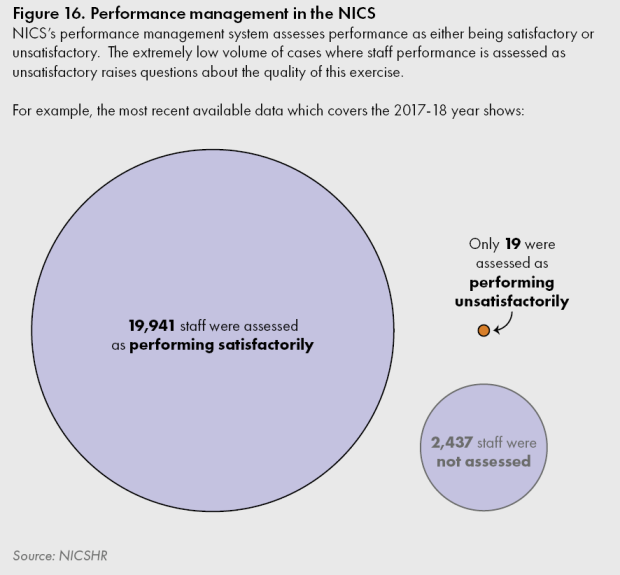

19 Number of unsatisfactory performance ratings in 2017-18 out of a workforce of over 22,000

Executive Summary

Background

1. A highly functioning Northern Ireland Civil Service (NICS) is crucial to the effective delivery of public services in Northern Ireland. At March 2019, over 22,000 people were employed by the nine NICS ministerial departments and their executive agencies, representing the third largest workforce in Northern Ireland. Total staffing costs for 2018-19 were almost £920 million.

2. Approximately 95 per cent of the NICS workforce are non-industrial staff who administer services, projects and programmes linked to the strategic priorities outlined in the 2016-2021 draft Programme for Government (PfG). Around two-thirds of these non-industrial roles are categorised as general service, with staff working in a wide range of roles including operational delivery, policy, and project or programme management.

3. In recent years, budgetary pressures have required the NICS to undertake a programme of workforce rationalisation, delivered through a voluntary exit scheme (VES) and a restructuring of NICS departments, the most significant machinery of government change since 1999. The NICS has also had to respond to several unprecedented challenges, including the suspension of the Northern Ireland Assembly for three years, preparing Northern Ireland for exiting the European Union (EU) and more recently, reacting to the coronavirus (‘Covid-19’) global health pandemic.

4. These challenges highlight the importance of a highly functioning NICS. However, serious weaknesses in the design and governance of the Non-Domestic Renewable Heat Initiative (RHI) scheme (‘the RHI Scheme’) have exposed deeper underlying concerns around the capacity and capability of the NICS to deliver complex programmes of this nature and are a key rationale for undertaking this report. The RHI Inquiry was set up to investigate the circumstances of the scheme and reported its findings in March 2020. Eleven of its 44 recommendations can be traced to shortcomings in either the capacity or capability of the NICS workforce. They cover areas such as leadership, the NICS professions, skills and experience in public finances, commercial awareness, contract and project management and the way the NICS recruits to its workforce. Appendix 3 outlines in detail the 11 recommendations.

5. Capacity involves having the ‘right-size’ workforce whilst capability relates to the workforce having the requisite skills, knowledge and expertise. Both are necessary to effectively deliver government initiatives as outlined in the draft PfG.

Key Findings

Workforce planning has been inadequate, and rapid progress is now needed to address significant vacancies and reduce reliance on temporary staffing solutions

6. Workforce planning throughout the NICS is not sufficiently developed to effectively manage a complex organisation with over 22,000 staff in a wide variety of roles across nine different government departments and their executive agencies. Prior to 2019-20, five of the nine NICS departments had no formal workforce plans in place and an NICS-wide workforce plan has not been developed.

7. In 2019, the NICS took steps to enhance workforce planning processes by introducing a new planning template for all NICS departments, covering the period 2019-2022. This progress is welcome, however, three departments could not provide us with even draft plans. The new template focuses exclusively on headcount and therefore does not consider the functional skills NICS departments require to deliver future government projects or programmes. However, the NICS HR function (‘NICSHR’) has advised that ‘a focus on headcount will establish a baseline – a fundamental element of effective workforce planning – from which further work will flow on the identification of the functional skills NICS departments require.’

8. Across the NICS, 45 per cent of staff are currently aged over 50, suggesting a significant number of retirements could occur in the next ten years. Unless significant workforce planning improvements are made and plans drawn up to address potential departures, the capacity and capability of the workforce could be significantly eroded.

9. In the absence of robust workforce planning arrangements and associated resourcing plans across all departments, the NICS has been poorly positioned to respond to increasing staff vacancy rates which, following the end of a moratorium on recruitment in 2016, have grown from 3.1 per cent in March 2017 to 6.9 per cent in March 2019. At March 2019, the total number of staff vacancies (1,420) exceeded the total workforce within the three smallest departments. This vacancy management situation has arisen in a period when the NICS should have been strengthening capacity, given that VES contributed to reducing total headcount by approximately 3,900 staff in the four year period to 2018-19.

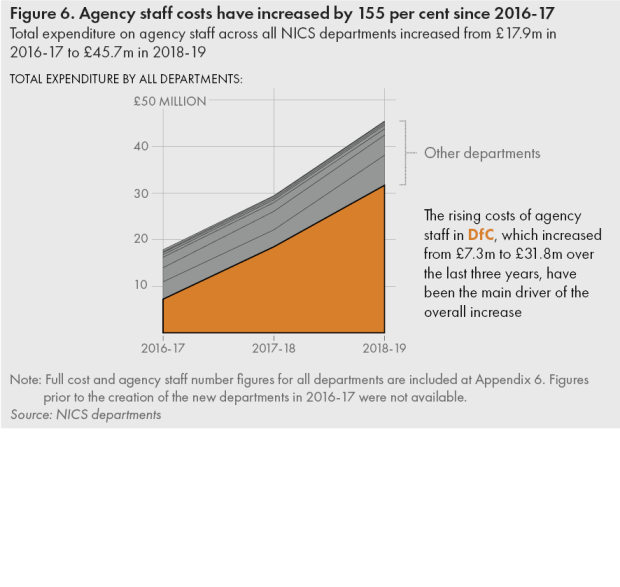

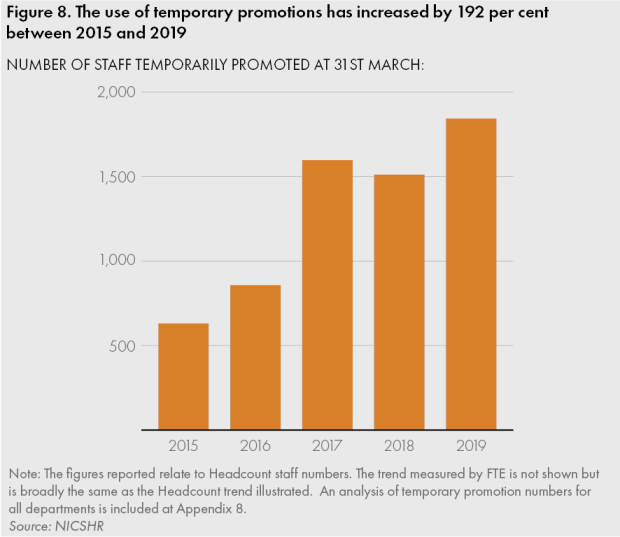

10. To partially address gaps in capacity, the NICS has used a variety of temporary staffing solutions, and has become reliant on agency staff in some areas to fill mainly junior (and some middle ranking) grades. The current agency worker framework utilised by the NICS, which had an overall anticipated cost limit of £105 million, has now been exceeded by £48 million. In 2018-19, the £45.7 million costs incurred by the NICS departments on agency staff represented a 155 per cent increase compared to 2016-17. Approximately 50 per cent of this relates to Department for Work and Pensions (DWP) benefit processing being undertaken in Northern Ireland by the Department for Communities (DfC). The use of temporary promotions across the NICS has also increased markedly, rising by 192 per cent between 2014-15 and 2018-19.

11. It is common for agency staff to be deployed for periods exceeding twelve months, and in 2019 at least six departments had cases of temporary promotions lasting longer than four years. Strong evidence therefore exists that temporary solutions are being used to plug permanent gaps in the NICS’s workforce capacity.

12. Positively, the NICS has recently sought to address the clear staffing shortfalls by undertaking large scale external recruitments, which have collectively aimed to attract substantial numbers of new permanent recruits at junior and middle ranking grades. Approximately a third of the candidates who were found to be suitable to date are external appointments with no former experience in the NICS, so those appointed should bring new skills, experience and values to the workforce.

Despite its importance to workforce capacity and capability, the current NICS recruitment approach does not support placement of ‘the right people in the right posts at the right time’

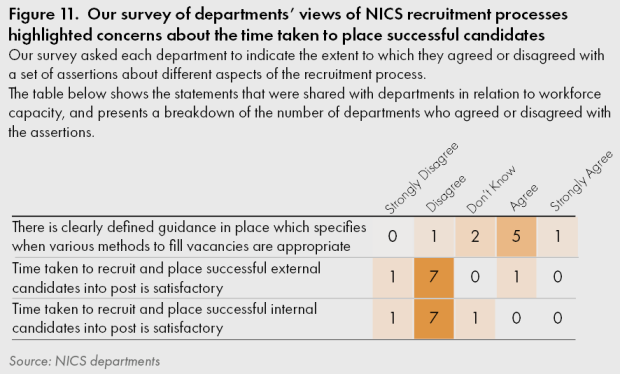

13. Current recruitment processes within the NICS are not adequately supporting it in addressing the significant vacancy management issues. In particular, NICS departments have significant concerns with the length of time being taken to place successful candidates in post, and have highlighted other issues which are contributing to the delays. These included their own inability to anticipate future supply need, the sequencing of promotions and timely access to departmental promotion lists.

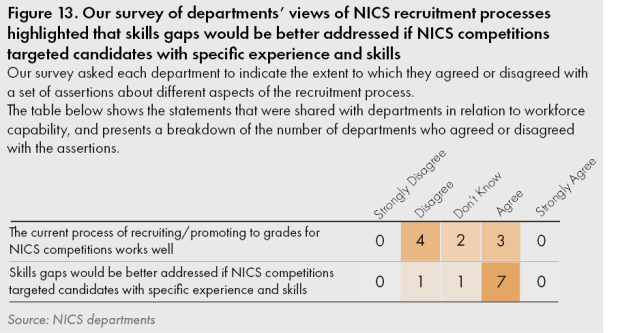

14. Although recruitment is also important in ensuring the NICS workforce has the required capability, currently NICS processes do not ensure ‘the right people are placed in the right posts’. General service appointments are not for specific roles and the recruitment and selection arrangements in place do not always assess the skills and experience of prospective candidates nor consider these when matching successful staff with vacancies. Instead, they mainly focus on testing competencies at interview. It is acknowledged however that the majority of specialist, professional, technical and Senior Civil Service (SCS) posts are recruited to specific roles.

15. Recognising the limitations of this approach, the Great Britain (GB) Civil Service recruitment process now assesses strengths, abilities, experience, technical skills and behaviours, as well as competencies. NICSHR plans to pursue this approach as part of a review of recruitment policy and process. The majority of departments recognise the need for change in this area, and agree that improving capacity and capability in the NICS requires the recruitment approach to change and be taken forward at pace. More recently, an NICS competition for general grades used a combination of assessment techniques, including competency-based interviews.

A stronger focus is required on developing functional skills within the NICS workforce

16. Unlike the GB Civil Service, the NICS has not yet adequately identified and provided a clear definition of the functional skill sets necessary for a high performing, modern NICS such as project management, commercial, contract management, data and digital technology, fraud and debt. We are aware, however, of certain instances of innovation and good practice within the NICS to build capacity and capability, but the lack of any central record of the skills and experience of NICS staff means there is no way of assessing if they are being utilised in areas that best match their abilities.

17. The RHI inquiry report confirmed the need for such functional skills in the NICS workforce. Our engagement with departments and analysis of their increasing use of the Strategic Investment Board (SIB) highlights a clear need for a wider capability and skills base across the NICS in areas such as project and programme management.

18. The NICS should now urgently apply an enhanced focus on functional skills. It currently has 24 recognised professions, however, there is little clarity on whether these staff, or those working in the larger general service workforce, possess sufficient experience or expertise in the key functional areas identified as crucial by the GB Civil Service (paragraph 16).

19. In terms of NICS professions, some have established entry standards, ongoing learning and development frameworks and career paths, but others are less formal and/or developed. Heads of Profession (HoP) are restricted in fully discharging their role, as they have to perform it alongside their substantive senior management position. While there are differences in the professions, establishing more defined and robust structures, together with sufficient resources, would enable the professions to establish and maintain a range of standards and better develop staff, thereby enhancing the capability of the NICS workforce.

We have significant concerns about the effectiveness of performance management in the NICS

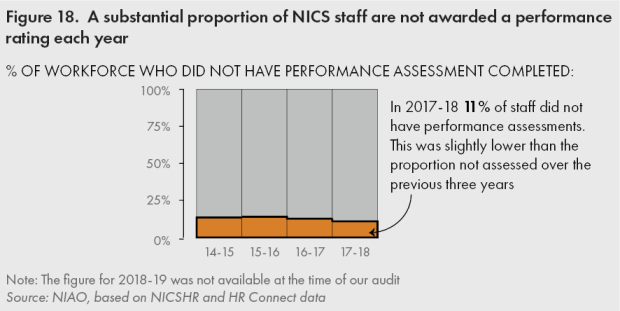

20. The current performance management system in the NICS only allows for staff to be rated as ‘satisfactory’ or ‘unsatisfactory’. Of almost 20,000 staff performance ratings awarded in 2017-18, 99.9 per cent (19,941 staff) received a ‘satisfactory’ rating, with only 0.1 per cent (19 staff) being assessed as ‘unsatisfactory’. Just over 2,400 staff did not receive any performance rating. NICSHR has advised that approximately 50 per cent of these staff would have been on maternity leave, sick leave or left the service. Further investigation of the remainder is still required.

21. Effective performance management can hugely benefit organisational development and growth but the current outcomes from the NICS performance management process raise significant concerns over its design and implementation. It is particularly difficult to see how the current system, and the culture generated, either incentivises improved performance or addresses performance shortcomings.

Leadership and talent management need to be strengthened across the NICS

22. The NICS staff surveys conducted in 2017 and 2018 identified concerns over leadership, with only 33 per cent of respondents expressing a degree of satisfaction, the lowest of all categories surveyed.

23. Leadership is an underpinning theme throughout the 2018-2021 NICS People Strategy and a range of leadership development initiatives have been introduced. Nonetheless it is too early to evaluate the overall success of these programmes and interventions. To date, an overarching talent management plan has not been developed.

24. As 80 per cent of the SCS is currently aged over fifty, succession planning and talent management is a key issue for the NICS. Work on expanding the NICS apprenticeship provision has been prioritised within the People Strategy, however it is concerning that the last general service fast track intake to the NICS was in 2014 which, in our view, is a retrograde step. More use of graduate schemes, alongside apprenticeship schemes, and other development initiatives aligned to the delivery of the NICS talent management and diversity and inclusion agenda, are essential in ensuring that the NICS has access to the skilled and experienced leaders that it needs now and in the future. Further action is now required to ensure a strong pool of skills and experience and to develop NICS future leaders.

Further work is vital to deliver an effective NICS Human Resources (HR) operating model and the implementation of its People Strategy to improve capacity and capability

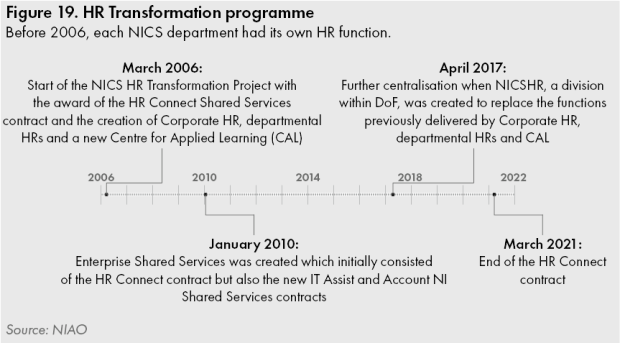

25. Since 2006, the NICS has taken incremental steps to try and transform the delivery of people management in the NICS, and adapt the supporting HR operating model. Following a review of the HR operating model in 2015, the NICS Board agreed a move to a single HR Centre of Excellence. In 2017, NICSHR was launched with the remit of delivering the services previously provided by the separate functions of Corporate HR, Centre for Applied Learning (CAL) and individual departmental HRs.

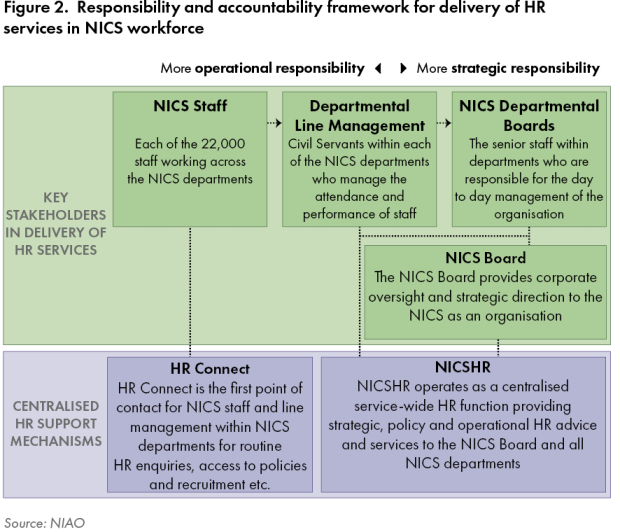

26. However, since 2006, a lack of NICS-wide strategic focus and under investment, coupled with the impact of preparing for EU exit and dealing with the Covid-19 situation, have led to no material headway in this transformation. To achieve further progress, we consider greater clarity is required on the roles and responsibilities of stakeholders within the model. This is highlighted by the results from our survey, where several departments expressed the view that the roles of certain stakeholders, including NICSHR, HR Connect and line management, are not clearly defined, whilst also advising that they have not been effectively fulfilling these roles.

27. The NICS People Strategy 2018 was an articulation of the transformation required for people management in the NICS, stating that there was “substantial enabling work to be done across the NICS by a variety of stakeholders to make the People Strategy a reality”. Unprecedented challenges along with resource limitations have hindered effective delivery of key aspects of the strategy which are crucial to improving the capacity and capability of the NICS workforce. The NICS operating context has necessitated a ‘get on and do’ approach, prioritising against the reality of its resource position.

28. The NICS has made progress on a range of actions, but the pace has been impacted by the reaction to culture change in the NICS along with other significant issues being faced (paragraph 26). It is now at a critical impasse, struggling to deal with current resourcing and other significant pressures and therefore unable to drive the transformation wanted and needed on key cultural change, long standing and longer term complex actions. This includes an overall joined up approach to talent management, strategic workforce planning and a fundamental review of recruitment and promotion.

29. These are not issues for the NICSHR function nor the Department of Finance (DoF) to address alone and will require senior leadership commitment across the NICS.

Overall VFM conclusion

30. At the heart of our findings, it is both evident and concerning that, for too long, workforce planning, organisational development and people management have been afforded inadequate priority and direction by the NICS. This is despite the fact that it employs over 22,000 staff and has responsibility for delivering critical government functions, objectives and vital public services. The out-workings of this are significant and include:

- an alarming rise in NICS staffing vacancy levels and increased reliance on temporary staffing solutions;

- workforce planning across the NICS which is not sufficiently developed to effectively manage a complex organisation with over 22,000 staff in a wide variety of roles across nine different government departments and their executive agencies and to address capacity and capability gaps;

- recruitment processes which are cumbersome and protracted, and have not been recalibrated to target and secure the necessary skills required to support a modern day civil service operating in a rapidly changing environment;

- inadequate progress in formally identifying and planning for the key functional skills required to meet current and future demands across the NICS; and

- performance management arrangements which require a radical overhaul.

31. Across the NICS, collaboration will be critical in approaching these important issues to realise the benefits which are achievable through much more joined up working and collective leadership. Against this background, we do not consider that value for money is being achieved in this crucially important area.

32. Despite the clear need to address a range of strategic weaknesses, it is important to recognise that NICS staff have continued to deliver vital services to the people of Northern Ireland during a period without an Assembly and against an unprecedented set of challenging circumstances, including the preparation for exiting the EU and responding to the Covid-19 pandemic. The NICS has recognised that action is required but strong collective leadership, driven by the new Head of the Civil Service (HoCS), will be critical to ensure the full implementation of the People Strategy 2018-2021 and the recommendations from both the RHI Inquiry and this report. Urgency, pace and investment is now needed as the NICS undertakes this transformation along with huge, but important, cultural change. Given the immense value that attaches to the work of public servants, now is the opportunity to drive this forward.

NIAO Recommendations

1. Leadership, governance and transformation

1.1 Further development of the operating model for people management and organisational development in the NICS is vital to ensuring it is in a position to deliver the scale and depth of transformation and cultural change needed. The NICS should therefore embrace good and successful models and practice from elsewhere.

1.2 Exceptionally strong leadership and a collective commitment is required to implement and prioritise, at the necessary pace, the remaining actions set out in the NICS People Strategy and the recommendations required by this report and the RHI Inquiry. This will necessitate some major strategic reform. Particular emphasis should be given to governance structures and clearly defined roles and responsibilities for all stakeholders including: the NICS Board; departmental boards; DoF; NICSHR; departments; line managers; contracted service providers for HR transactional services; and the Civil Service Commissioners.

1.3 There should be absolute clarity on who will oversee the transformation required and it is imperative that this is sufficiently resourced.

1.4 To further enhance accountability, all senior civil service staff should have capacity and capability related objectives in their annual performance expectations, along with measurable targets.

2. Workforce planning

2.1 A key goal of workforce planning should be to ensure departments have the necessary resources and skills to deliver key programmes and objectives. Workforce planning should be underpinned by accurate and robust data, including clarity around underlying assumptions in key areas of vacancies, temporary staffing solutions, alternative work patterns and partial retirees.

2.2 An NICS-wide workforce plan should be developed to include both headcount and skills, informed by a workforce planning template applied consistently across departments, and further developed to assist succession planning.

2.3 The NICS staffing costs profile should be reviewed, including costs of all temporary staffing solutions, to inform whether permanent staffing budgets and headcount baselines require adjustment to better align workforce planning to NICS staff requirements.

3. Review of resourcing

3.1 Alongside improvements in workforce planning, a fundamental review of resourcing should be undertaken, focusing on recruitment and selection methods. To place the right people in the right posts, appointments should be to roles or role categories with essential and desirable criteria tailored as appropriate. The emphasis should be on testing the required skills and experience within the recruitment process as well as the competencies and, where appropriate, using these when matching staff to vacancies.

3.2 The resourcing approach should include more external recruitment and a targeted use of secondments and the interchange system. The use of SIB should remain an option, provided departments comply with The Executive Office’s (TEO’s) engagement principles and procedures, including effective arrangements for governance and oversight.

3.3 The NICS should, on an ongoing basis, review and ensure that its arrangements in relation to market based pay flexibilities and non-salary incentives are appropriate to attract and retain in-demand skills. If the NICS needs to transition to more attractive arrangements, effective oversight and governance should be established to ensure value for money.

3.4 The NICS and the Civil Service Commissioners should work in partnership, taking account of how other models operate, to explore how they can best support the delivery of the transformation agenda and the changes needed to reform the recruitment and selection process throughout the NICS.

4. Vacancy management processes

4.1 Improvements in workforce planning and changes to the NICS approach to recruitment and selection processes should be supported by improvements to operational vacancy management processes, to provide a more flexible and responsive approach and reduce the time taken to place candidates in posts.

4.2 Improved workforce planning should identify vacancies earlier and associated resourcing plans should be developed. Vacancy management processes should be refined; duplication and delays should be removed; roles and responsibilities within the processes should be clear and understood by all stakeholders; best practice timescales for recruitment competitions should be agreed and monitored by the NICS and departmental boards; and more reliable processes for estimating future supply needs and contingency should be introduced.

5. Skills

5.1 The NICS should formally identify the professional, technical and functional skills it requires to successfully deliver current and future government programmes.

5.2 Each NICS department, applying the same overall methodology and using the same definitions, should undertake formal and ongoing skills audits, to capture intelligence about existing workforce skills, background and experience and store this information on a centralised database. The resulting database should be continually updated and contain sufficient detail to assist departments with workforce planning, succession planning, vacancy management, recruitment, learning, development and talent management. The skills audits process should form part of a continual skills assessment cycle.

5.3 A skills gap analysis, focusing on critical skills such as project management, commercial, contract management, data and digital technology, fraud and debt, should be undertaken. The NICS should outline how these skills will be acquired and developed within its workforce, with specific consideration given to the creation of new NICS professions and an enhanced role for existing NICS professions, potentially coupled with the development of a functional skills model aligned with that of the GB Civil Service.

5.4 All resulting NICS professions, or functions, especially the larger ones or those requiring accelerated development, should be provided with sufficient support and resources, to lead and develop the capabilities of the profession/function, to meet NICS professional skills demands.

6. Performance Management

6.1 The NICS performance management approach, process and guidance should be improved to recognise strong performance, appropriately manage under performance, and incentivise staff to improve and develop. Creating an effective performance management culture will require strong leadership and open, honest and clear communication. The process should be supported by clear guidance to ensure consistency of approach.

6.2 Compliance and consistency across all grades is critical and, to this end, the approach should contain quality-themed compliance checks.

6.3 There should be a continued focus on strengthening the capacity and capability of line managers at all levels in the NICS to deliver on improved performance management and other key areas impacting on capacity, such as managing attendance.

7. Talent management, learning and development

7.1 There should be a clear commitment to initiatives such as employability programmes, apprenticeships, graduate and fast-track schemes, not solely for general service grades but also for any new profession or functions arrangements (Recommendation 5.3), underpinned by on-the-job training, mentoring and other support mechanisms.

7.2 The NICS strategic response to, and leadership role in, the Executive’s Covid-19 recovery plan means that the civil service’s approach to talent management is now more important than ever. It should be further developed and communicated as a clearly defined, prioritised and resourced strategic plan to support change and drive initiatives to help guide recruitment and selection, performance management, workforce planning, succession planning and learning and development.

7.3 The NICS should develop a learning and development plan which, like the diversity plan, is aligned to the People Strategy and should be informed by departmental skills audit outcomes and take account of line of business training within departments and NICS professions or functions requirements (Recommendation 5.2).

Part One: Introduction and Background

The NICS plays a fundamental role in delivering the Northern Ireland Executive’s strategic priorities

1.1 The Northern Ireland Civil Service (NICS) is a permanent institution which supports the Northern Ireland Executive. Its principal role is to develop and implement government policies and help administer and oversee the delivery of services to the public of Northern Ireland.

1.2 There are nine NICS ministerial government departments, each with key operational responsibilities (Figure 1). These align to the Northern Ireland Executive’s strategic priorities as set out in its draft Programme for Government (PfG) document 2016-2021.

Figure 1: NICS departments - Key operational responsibilities

|

Department |

Responsibilities |

|---|---|

|

The Executive Office (TEO) |

Overall responsibility for running the Northern Ireland Executive |

|

Department of Agriculture, Environment and Rural Affairs (DAERA) |

Overall responsibility for assisting in the sustainable development of the agri-food, environmental, fishing and forestry sectors of the economy |

|

Department for Communities (DfC) |

Overall responsibility for tackling disadvantage and building sustainable communities |

|

Department of Education (DE) |

Overall responsibility for delivering pre-school, primary, post primary and special needs education |

|

Department for the Economy (DfE) |

Overall responsibility for the promotion and development of the economy |

|

Department of Finance (DoF) |

Overall responsibility for ensuring the most appropriate and effective use of public resources |

|

Department for Infrastructure (DfI) |

Overall responsibility for maintaining and developing transport and water infrastructure |

|

Department of Health (DoH) |

Overall responsibility for improving health and social wellbeing of the people |

|

Department of Justice (DoJ) |

Overall responsibility for policing and justice powers |

Source: NIAO

1.3 To secure effective delivery of the draft PfG, collaborative and cross-departmental working is required by NICS departments. The capacity and capability of the NICS is key to helping it successfully deliver the draft PfG’s fourteen intended societal outcomes.

A high performing workforce requires the right Capacity and Capability.

Capacity is having the ‘right-size’ workforce.

Capability is having a workforce with the requisite skills, knowledge and expertise.

The NICS workforce is the third largest in Northern Ireland and comprises various grades and professions

1.4 At April 2019, the nine NICS departments employed 22,313 members of staff, or 20,725 Full Time Equivalents (FTEs). This is the third largest workforce in Northern Ireland, with only the health and social care and education sectors having more staff. Total staffing costs for the nine NICS departments amounted to £917.6 million in 2018-19.

1.5 The NICS workforce comprises a range of industrial and non-industrial staff grades as well as a senior management stream (the Senior Civil Service - (SCS)). Industrial staff, which account for around 4 per cent of the workforce, perform mainly frontline operations. This report, however, primarily focuses on the non-industrial civil servants that represent 95 per cent of the workforce and have a grading structure ranging from Administrative Assistants (entry level) to Grade 6 (management level). Within the SCS, staff at Grade 5 and Grade 3 level report to the Permanent Secretaries of the nine NICS departments, who are accountable for the day to day operation of the business.

1.6 The above analysis is based on Appendix 1 which sets out the NICS grading structure and the number of FTEs employed by the nine NICS departments.

1.7 At April 2019, approximately two-thirds of non-industrial NICS staff occupied general service posts, performing a wide range of roles including operational delivery, policy and project or programme management. For these staff, movement between such roles is common practice. There are also 24 recognised NICS professions to which professional and technical staff and also general service staff may belong (Appendix 2).

1.8 The nine departments differ in terms of staff numbers, grades, skills, knowledge and expertise. A number of factors determine the optimal workforce requirements of each department including:

- line of business functions and strategic objectives;

- the technical demands of the sector, such as Infrastructure or Health; and

- the scope and complexity of projects to be delivered.

Responsibility for NICS capacity and capability lies with Permanent Secretaries, with various stakeholders providing human resources (HR) support

1.9 To function effectively and deliver the required outcomes, NICS departments require ‘the right people, in the right place, at the right time’. Permanent Secretaries are accountable to their respective Minister for their departments’ overall performance and therefore are responsible for obtaining the appropriate staffing resources. In turn, Ministers are answerable to the Northern Ireland Assembly.

1.10 In managing the NICS workforce, the Permanent Secretaries and the various line managers within their command are supported by a range of other relevant stakeholders within the people management and leadership model. A high level illustration of the current HR service operating model for the NICS (Figure 2) includes HR Connect, which assists with everyday HR and payroll enquiries, and the NICS HR function (‘NICSHR’) which provides policy development and operational support and advice on strategic and more complex HR issues.

1.11 Created in April 2017, NICHSR brought together the functions of Corporate HR, Departmental HR and the Centre for Applied Learning (CAL) and it currently has 430 FTE staff. HR Connect Service Management Division within DoF’s Enterprise Shared Services (ESS) has a complement of 9 FTEs and manages the services provided by HR Connect to the NICS. Both units are part of DoF. The Civil Service Order 1999 makes DoF (formerly the Department of Finance and Personnel) responsible for the general management and control of the NICS. The Department may make regulations or give direction on;

- the number and grading of posts within the civil service and employment;

- regulations or directions relating to remuneration, expenses, allowances, conditions of service, classification or re-classification of civil servants;

- the Code of Conduct and Code of Ethics; and

- recruitment for the NICS.

1.12 The NICS Board, which is a senior management leadership forum chaired by the Head of the Civil Service (HoCS), and attended by the nine Permanent Secretaries along with various other stakeholders, also considers workforce requirements and people issues from a strategic perspective. It provides corporate oversight and strategic direction to the NICS as an organisation and has recognised the need to improve capacity and capability of the wider NICS workforce by agreeing its People Strategy in May 2018.

Successful workforce planning is fundamental to building NICS capacity and capability

1.13 Successful workforce planning ensures that an organisation has both appropriate capacity and capability i.e. the right number of staff with the requisite skills, knowledge and experience. Alongside this, organisations must have effective processes for deploying, managing and developing their workforce.

1.14 In recent years, local public sector bodies, including NICS departments, have faced increasing challenges in ensuring that their workforces are equipped with the required capacity and capability. Indeed, as Appendix 3 outlines, inadequate capacity and capability has contributed to various shortcomings within key NICS programmes and projects.

1.15 The serious weaknesses in the design and governance of the Non-Domestic Renewable Heat Incentive Scheme (‘the RHI scheme’), have exposed deeper underlying concerns around the capacity and capability of the NICS to deliver complex programmes of this nature. In providing evidence to the Independent Public Inquiry into the RHI Scheme (‘the RHI Inquiry’) in March 2018, the HoCS acknowledged that the former Department of Enterprise, Trade and Investment

(DETI) had taken risks by relying on a small team of general service staff with limited, relevant expertise, to deliver such a complex project. The RHI Inquiry subsequently criticised the capacity and capability of the project team, stating that:

“The Inquiry finds that the resources available to develop this novel and complicated scheme were inadequate. The insufficiency of resources was not only in terms of staff numbers: the small team was simply not provided with the necessary knowledge or experience to carry out the necessary activities; to analyse the information it received; to make the necessary judgments; nor was there any adequate effort to access expertise in other parts of the Northern Ireland Government such as Invest NI and/or the Strategic Investment Board”.

1.16 Such shortcomings highlight the importance of public bodies giving sufficient priority on an ongoing basis to developing strong workforce planning arrangements which address capacity and capability gaps.

The NICS has been operating in a changing environment

1.17 Effective workforce planning is challenging and is complicated by constant changes in work priorities and the operating environment of NICS departments. In recent years, the NICS has faced unprecedented challenges which have made workforce planning increasingly difficult. For example:

- The out-workings of the Public Sector Transformation Programme in Northern Ireland. This was administered across the NICS departments in 2015-16 via a Voluntary Exit Scheme (VES) and achieved estimated annual staff cost savings of £87 million. This contributed to a reduction in NICS workforce numbers of 15 per cent between 2014-15 and 2018-19.

- The annual budget-setting cycle in central government, combined with the suspension of the Northern Ireland Assembly, inevitably hampered longer term financial and workforce planning. This consequently impacted on the NICS’s ability to permanently fill vacancies with the ‘right’ people.

- The NICS departments have faced considerable pressures associated with preparing for exiting the European Union (EU), with significant staffing resources being devoted to this and staff being redeployed from delivering other key services, and, in 2020, responding to the coronavirus (‘Covid-19’) pandemic.

1.18 In essence, the NICS has been expected to deliver existing services with fewer permanent staff whilst responding to these challenges. To address capacity and capability shortfalls, NICS departments have deployed a range of temporary measures including using temporary promotions, agency staff and overtime. The annual expenditure associated with these measures has increased by £30.5 million between 2016-17 and 2018-19.

Scope and structure

1.19 This review is effectively a position statement of the capacity and capability within the NICS workforce. In assessing capacity we focused on workforce planning, vacancy management and staff recruitment, as well as the growing use of temporary measures to address staffing gaps. In the area of capability we reviewed the current NICS skills base and sought to identify potential gaps, and the necessary steps needed to acquire the requisite and specialist skills. We also examined whether the current NICS professions structure is effectively meeting the increasingly challenging and complex demands being placed on NICS departments, as well as current arrangements for managing staff performance and addressing training and development needs.

1.20 Our report is strategically focused and structured as follows:

- Part Two- an assessment of the challenging environment facing the NICS.

- Part Three- whether the NICS workforce has sufficient capacity, and how this can be further enhanced.

- Part Four- whether the NICS workforce has sufficient capability, and how any key skills gaps can be addressed.

- Part Five- work ongoing within the NICS to address capacity and capability needs and the challenges which still remain.

1.21 Our review used a range of investigative and research methods (Appendix 4).

1.22 Whilst this study has focused on the NICS, all public sector bodies across Northern Ireland should consider the findings in the context of their own operations and develop action plans to address any key shortcomings.

Part Two: The NICS has had to deliver existing services whilst rationalising its workforce

and structure and responding to unprecedented challenges

2.1 ‘The Stormont House Agreement’ (December 2014) and ‘A Fresh Start: The Stormont Agreement and Implementation Plan’ (November 2015) committed the Northern Ireland Executive to introducing comprehensive reform and restructuring designed to maximise available resources and deliver enhanced services to citizens.

2.2 This led to the introduction of public sector VESs to reduce pay-bill costs. The NICS VES operated in 2015-16 and was followed by departmental restructuring. A temporary recruitment and promotion freeze was also introduced in November 2014 but was withdrawn in April 2016 partly due to the impact of VES on the capacity of the NICS workforce.

While VES delivered cost savings and workforce rationalisation, the NICS workload has not reduced

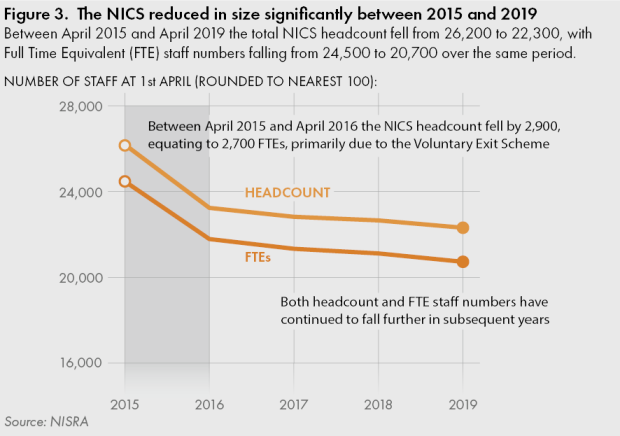

2.3 Funding for VES was managed and allocated across the NICS departments by the former Department of Finance and Personnel (DFP) (now DoF). The scheme was operated by the NICS departments in 2015-16 and on completion, incurred costs of £90.4 million. Whilst it helped achieve estimated annual cost savings of £87 million, it was also the primary reason for total headcount and FTEs falling across NICS departments by 3,900 and 3,800 respectively between 2015 and 2019 (i.e. a 15 per cent workforce reduction) (Figure 3).

The scheme particularly impacted on workforce numbers in the former Department for Regional Development (DRD) (now DfI), which reduced by 15 per cent in 2015-16 alone.

2.4 The NICS told us that staff numbers continued to fall modestly by around 4 per cent between 2016 and 2019 after the completion of VES, due to NICS departments not filling all of the vacancies which emerged when NICS staff left. This practice occurred as most departments wanted to preserve the savings generated by VES. The sustained use of internal promotion boards and appointments rather than open recruitment, also meant there was little opportunity to increase the overall headcount numbers.

2.5 Shortly after VES was introduced across the NICS, significant departmental restructuring also commenced (May 2016). This represented the biggest change to the machinery of government in Northern Ireland since 1999. It reallocated responsibilities from the previous twelve NICS departments to nine new departments. In announcing the NICS restructuring in March 2015, the then First Minister confirmed that all existing functions and policies were being maintained, but the focus would be on delivering these more efficiently.

2.6 The impact of such significant restructuring, combined with the considerable reduction in staff numbers, has contributed to weakening the NICS’s capacity and capability to deliver services. Our report in 2016 on VES found that:

- there had been some increases in expenditure on agency staff and consultancy following the implementation of VES; and

- although departments confirmed VES had helped secure operational efficiencies, it had been detrimental to staff morale and led to a loss of key skills.

Mechanisms existed within the VES scheme to mitigate against the loss of vital skills, including quotas and phased tranches, etc. However, of 25 organisations surveyed, nine reported losing key skills.

2.7 This investigation has found evidence that key gaps remain. The DoJ reported a shortage of specialist skills in Forensic Science Northern Ireland (FSNI) and the Northern Ireland Courts and Tribunal Service (NICTS). The DfC told us it was still missing skills in the Public Record Office of Northern Ireland (PRONI), which has damaged its ability to engage proactively with NICS departments to fully deliver its statutory obligations, and the DfI has lost a significant number of professional and technical staff with sector specific knowledge and experience of the Northern Ireland roads and waterway networks.

Annual budget-setting and the suspension of the Northern Ireland Assembly have restricted longer term planning

2.8 This comprehensive NICS reform and restructuring coincided with government austerity measures which have reduced the overall Northern Ireland block grant by £530 million since 2010-11. Although the NICS departments have attempted to manage and control the increasingly tightened budgets, the annual budget-setting cycle has hampered more effective longer term financial and workforce planning.

2.9 The Northern Ireland Assembly’s suspension in January 2017 presented further challenges. Decision making across the NICS was restricted to implementing existing policy, with no scope for introducing new policy as the necessary legislation could not be passed. This has had a negative impact on the NICS’s ability to strategically plan for the future. Eight of the nine NICS departments told us that the absence of a fully functioning Assembly had caused them operational issues which have impacted on their capacity and capability.

2.10 A concerning outworking of this, and of the VES scheme, is that the NICS has become more reliant on temporary staffing solutions, including the use of agency staff (Part Three examines the use of temporary measures in the NICS in greater detail).

The NICS has also had to deal with unprecedented challenges

2.11 In addition to significant staffing and structural rationalisation, the NICS has faced a number of other challenges, including further reform initiatives and unprecedented political and global health developments:

- Welfare Reform: implementing welfare reform has presented the DfC with significant pressures. In 2019, we reported that whilst the DfC had estimated the cost of implementing welfare reforms in Northern Ireland at more than £0.5 billion over a ten year period, no additional funding had been allocated to cover this.

- Exiting the EU: Exiting the EU has impacted significantly on all sectors in the United Kingdom (UK). In Northern Ireland, engagement on exiting the EU has been taken forward by the NICS departments. Significant transitional work has been necessary in preparation for EU responsibilities being returned to the UK. This has included addressing key areas such as migration, EU market access, future trade policy and energy under various ‘deal’ or ‘no deal’ scenarios. It has required draft amendments to legislation, detailed consideration of operational implications, and close liaison with Civil Service counterparts across the UK. Consequently, already limited NICS staff resources have had to be redeployed from mainstream service delivery. A report commissioned in early 2019 found an EU exit resourcing requirement across the NICS of between 400 and 760 staff, depending on a `deal’ or ‘no deal’ scenario.

- Covid-19: The global transmission of Covid-19 could not have been foreseen, but has placed a huge burden on countries throughout the world. Urgent efforts have been required to increase intensive care capacity, undertake microbiological testing, develop and administer grants for small businesses and quickly increase welfare benefit provision. Diverting resources to respond to new and urgent government initiatives, alongside the measures of ‘self-isolation’ and ‘social distancing’, further reduced NICS workforce capacity, and impacted on the efficient delivery of wider day to day services.

Addressing current and future challenges will require the NICS to enhance its capacity and capability through strategic organisational development and transformation

2.12 This part of the report has highlighted complex challenges which the NICS is still in the process of addressing. Despite these significant obstacles, the NICS has continued to function and provide important services to the people of Northern Ireland. A 2019 Institute for Government review applauded the NICS for how it had handled the absence of ministers, but also highlighted the need for improvement in certain areas, including the capability shortfalls highlighted by the RHI Inquiry. For the NICS, in common with many organisations, the unprecedented challenge presented by the Covid-19 pandemic is also likely to provide important experience and lessons learnt in the areas of business continuity planning and processes.

2.13 The January 2020 ‘New Decade: New Approach’ document included updated commitments by the restored Executive to deliver further public sector transformation and investment. In order to manage this process effectively, it is therefore crucial for the NICS to identify its optimal capacity and capability so that the right number of people with the necessary skills are in the right places at the right time across all departments. This will require an enhanced focus on a wide range of areas including:

- strategic workforce and succession planning;

- recruitment and vacancy management;

- the use of temporary staffing solutions, skills and professions;

- sickness absence;

- performance management;

- training and development; and

- leadership and talent management.

2.14 Parts Three and Four of this report consider these issues. The associated recommendations are documented in the Executive Summary.

Part Three: Significant work is needed to address NICS capacity gaps

3.1 Previous Northern Ireland Audit Office (NIAO) reports (Appendix 3) have highlighted how capacity related shortfalls have impacted across the public sector in Northern Ireland, including the health sector, oversight of major capital projects and management of the government office estate.

3.2 This part of the report examines the current capacity within the NICS workforce and assesses if a number of factors could pose risks and threats to how the NICS is positioning for the future.

NICS sickness absence rates are almost twice the level of the other UK civil services

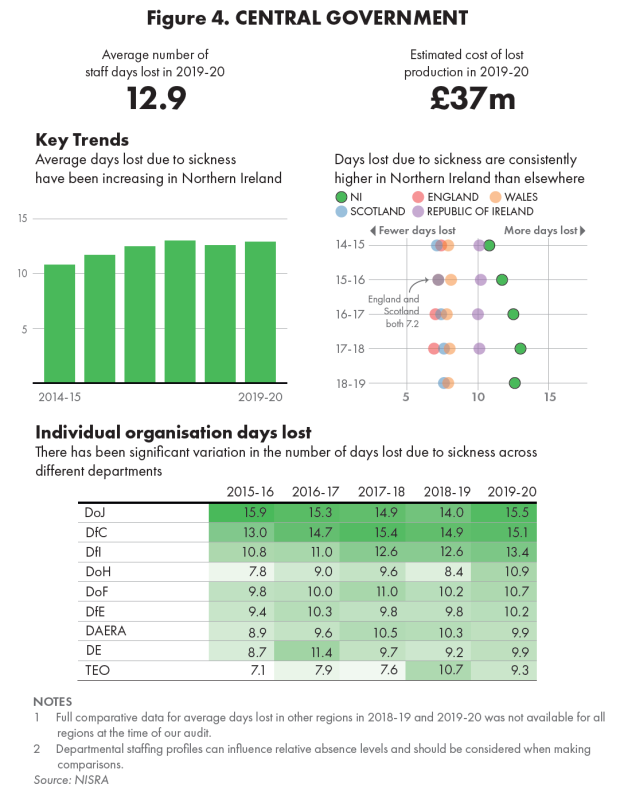

3.3 The rate of sickness absence is an important and relevant indicator for measuring the health and wellbeing of the workforce. Good health and wellbeing helps increase employee motivation, engagement and output.

3.4 The Northern Ireland Statistics and Research Agency (NISRA) publishes annual statistics on NICS sickness absence, together with an analysis of trends over time. The overall average level of sickness absence per employee across the NICS increased each year from 2014-15 (10.8 days) to 2017-18 (13.0 days). This compares favourably with equivalent statistics for local councils in Northern Ireland during the same period (12.3 to 14.9 days respectively). In 2018-19 the NICS figure reduced slightly to 12.6 days.

3.5 The most significant cause of absence was anxiety, stress, depression or other psychiatric illnesses, which collectively accounted for almost 39 per cent of days lost in 2018-19. Within this category, work related stress accounted for approximately a third of the days lost. NICS sickness absence rates are highest for staff aged 55 and over (14.3 days).

3.6 NICS sickness absence levels appear however to be significantly higher than for civil servants elsewhere in the UK (Her Majesty’s Civil Service (‘GB Civil Service’), Scotland and Wales) (Figure 4), but caution needs to be exercised in making comparisons, as methodologies for gathering and reporting data can differ across organisations.

3.7 NISRA estimates that the average 12.6 days lost for each staff member in 2018-19 equated to approximately 268,000 days absence, with estimated pay bill equivalent costs of £32.9 million. This high sickness absence level across a headcount of over 22,000 can only have reduced the strength of NICS capacity and capability, so addressing the area is clearly a matter of priority for the NICS. Particular focus should be applied to the most significant causes of absence.

Vacancy rates have increased in almost all NICS departments

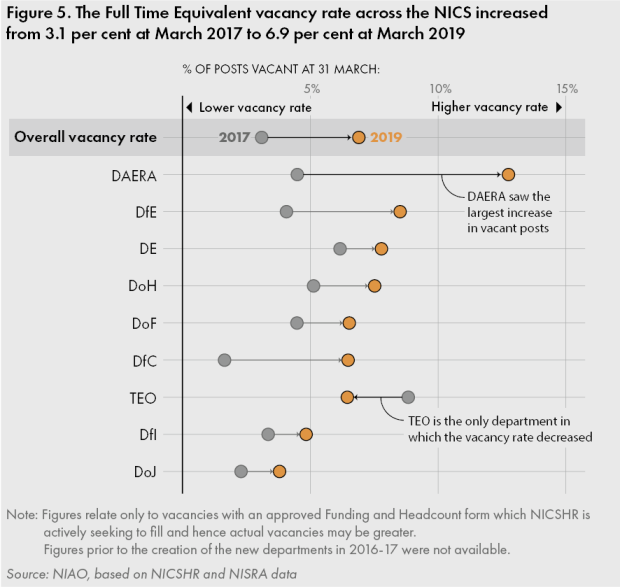

3.8 In Part Two, we highlighted how the permanent NICS workforce has been contracting, largely due to VES, whilst still having to maintain delivery of all existing services and respond to a range of unprecedented challenges such as preparing to exit the EU. Against a background where the NICS should have been strengthening its capacity, vacancy rates since March 2017 have shown a relatively large increase in all but one of the NICS departments. At March 2019, there were 1,420 FTE vacancies across the NICS which equates to 6.9 per cent of the workforce. This exceeds the combined total FTEs for the three smallest NICS departments (DE, DoH and TEO) and represents a very significant increase on the 666 vacancies (3.1 per cent) recorded at March 2017 (Figure 5). As noted earlier at paragraph 2.4, the NICS was emerging from VES, post April 2016, which resulted in NICS departments not filling all vacancies when NICS staff left.

3.9 NICSHR has told us the current vacancy situation is “unsustainable” and most of the NICS departments identified this as an area of concern. For example, only two departments stated that their vacancy management processes were fully meeting expected requirements and did not need improvement. The departments attributed the current vacancy levels to a number of factors including:

- the additional need for staff, for example, to prepare for exiting the EU (particularly within DAERA), for undertaking transformation projects (DoF and DoH), or for responding to the requirements of the RHI Inquiry (DfE and DoF); sequencing of promotions and restrictions on accessing other departments’ ‘promotion lists’;

- supply issues at junior and middle management general service grades (Administrative Officer (AO) to Deputy Principal (DP)), resulting in an increased reliance on temporary staffing measures such as agency staff or temporary promotions;

- time taken to appoint staff (paragraphs 3.44 to 3.49); and

- difficulty in identifying the right people for specific roles.

3.10 Furthermore, the above data does not reflect how the re-establishment of the Northern Ireland Assembly in early 2020 has created further vacancy pressures across the NICS, due to staff previously redeployed to other NICS departments returning to their substantive Assembly posts.

3.11 Whilst effectively filling vacancies should now be a key priority across the NICS, slow progress in addressing longer term workforce planning (paragraph 3.32 – 3.35) has made the reduction of the current high vacancy rates challenging. To help NICS departments, NICSHR has recently introduced several interim measures, including improved communication with line managers on forthcoming promotion lists and ongoing development of better quality management information on staffing levels and needs. A vacancy management toolkit is also under development. In addition, NICSHR has advised us that in response to immediate concerns around EU exit planning and the Covid-19 pandemic, it has developed a recruitment plan in conjunction with departments, focusing on staff requirements over the next 6-9 months.

3.12 All the departments agree that a more structured approach to public sector secondments and better use of the Interchange Scheme offer other potential methods of temporarily reducing vacancy levels. Seven out of the nine departments also advocated increasing the use of external recruitment to improve vacancy management.

The NICS has become increasingly reliant on temporary staffing solutions

3.13 The rising vacancy levels have been a key contributory factor behind an increased reliance across the NICS on temporary staffing solutions. These temporary measures include the use of agency staff, overtime and temporary promotions. These options at times provide valuable support to the NICS departments and can offer value for money if properly managed and controlled, however, the sustained and increasing use of agency staff and temporary promotions is concerning.

3.14 Case Study 1 illustrates how the NICTS, an executive agency of the DoJ, has through necessity used temporary staffing solutions to maintain its core business functions. Based on our stakeholder engagement, it usefully portrays the ‘firefighting’ approach that some central government organisations are currently using.

Case Study 1

Northern Ireland Courts and Tribunals Service (NICTS)

Difficulties in recruiting and retaining staff have resulted in rising vacancies in both general service posts and specialisms including legal advisors, accountants and project delivery. The NICTS has therefore had to use a range of temporary staffing solutions in recent years, most significantly temporary promotions which have increased by 123 per cent in the three years to March 2019. At this date, 58 staff were temporarily promoted in the NICTS, equating to just over 8 per cent of its workforce.

These measures have enabled the NICTS to maintain essential court business but the staffing pressures have still continued to impact negatively on the implementation of its longer-term Modernisation Programme. Tasks have been reprioritised and some projects postponed, including the Probate and Income Channel Shift initiatives, which could potentially undermine the realisation of longer term benefits.

Staffing pressures still exist within the NICTS, in particular:

- a vacancy rate of 13 per cent, despite staff in post numbers actually increasing by 45 in the three years to March 2019;

- high staff turnover for various reasons; and

- training pressures due to a lack of continuity of staff and knowledge transfer.

The NICTS and NICSHR are working closely to address the organisation’s recruitment and retention issues.

Agency staff

3.15 Our report in 2016 on the Northern Ireland Public Sector VES found that there had been some increases in expenditure on agency staff and consultancy following the implementation of VES. It advised that ongoing monitoring of staff costs could help identify where reductions achieved by VES on pay bill expenditure was being displaced into agency or consultancy expenditure.

3.16 Since then, reliance on agency staff in some areas has continued to increase across the NICS. The number of agency staff working in the NICS departments has increased by 100 per cent, from 1,047 to 2,099 between March 2017 and March 2019. Approximately 50 per cent of these are linked to an increase in Department for Work and Pensions (DWP) benefit processing work being undertaken by the DfC. It is important to note that the cost of this work does not fall to the NICS but to DWP. This increase in the number of agency staff saw total agency costs for the period increase by 155 per cent, from £17.9 million to £45.7 million (Figure 6).

3.17 In addition, the current agency worker framework, which includes provision for both generalist and specialist roles, has exceeded its envisaged cost limit of £105 million by £48 million (46 per cent). Agency staff have mainly been used to fill ‘capacity’ gaps across junior general service grades. However, seven of the nine departments also acknowledged using agency staff over the last three years to meet `capability’ needs, including filling specialist roles such as legal posts, accountants, statisticians, valuers and auditors. Information was not available to determine the proportion of vacancies (paragraph 3.8) filled through agency staff.

3.18 The agency worker framework should only be used to fill short term vacancies required for urgent business needs that cannot be met in any other way. It should not be used to fill posts for indefinite periods, as this would indicate the work on which agency staff are engaged is not temporary and should, therefore, be filled substantively (e.g. by fixed term or permanent recruitment). Our review of the NICS workforce and pay-bill monitoring report at March 2019 highlighted that approximately 70 per cent of all agency workers were covering permanent, non-temporary positions. Although agency workers are broadly paid the same salary rates as NICS staff, departments incur additional contractual costs in fees payable to agency providers. Indirect costs also arise with administering the process, exacerbated by high rates of attrition, as well as non-quantifiable costs, including lost productivity whilst new workers are trained and upskilled. In our view, the high reliance on these arrangements is unlikely to be providing the NICS with value for money.

3.19 An NICS-wide analysis of the average length of time in post for agency workers was not available to inform our review. However, information provided by five departments indicated they had employed agency staff for greater than twelve months. In DoF and DAERA, 29 per cent of agency workers (75 and 38 respectively) had been in post greater than twelve months.

3.20 To address permanent workforce shortages at junior but also middle management levels, and reduce reliance on agency workers, the NICS has recently sought to address the clear staffing shortfalls by undertaking large scale open recruitment competitions for the AO, Staff Officer (SO) and DP grades. These competitions are ongoing and aim to attract approximately 1,400 permanent recruits (subject to final confirmation of needs from departments).

Overtime

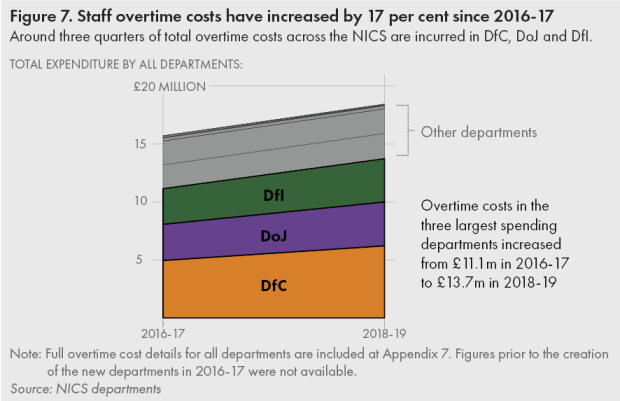

3.21 As well as being increasingly reliant on agency staff, overtime costs across the NICS departments have also risen by 17.4 per cent, from £15.6 million in 2016-17 to £18.4 million in 2018-19 (Figure 7).

3.22 Whilst the figures are modest in terms of overall NICS staffing costs, overtime should again only be a short term solution to capacity issues. Prolonged use of overtime can have wider negative impacts on employee health and wellbeing, work-life balance, morale, productivity and absenteeism. It therefore needs to be kept under scrutiny.

Temporary promotions

3.23 Temporary promotion of internal staff to cover vacant posts or staff absence is another option used by the NICS departments to manage workforce gaps and deliver their operational objectives. Although the annual cost of NICS temporary promotions was unavailable, data was provided by NICSHR on the number of staff temporarily promoted over the last five years. Across the NICS, the overall number of temporary promotions has increased by 192 per cent between 2015 and 2019, from 631 to 1,844 (Figure 8). In 2019, this equated to 8.2 per cent of the overall NICS workforce. Of the vacancies reported at paragraph 3.8, approximately 50 per cent were filled through the use of temporary promotion.

3.24 Temporary promotions have increased in seven of the nine NICS departments since restructuring in May 2016. The DoH has recorded an increase of 90 per cent in this period. This is mainly because transformation projects needed to be progressed within a limited timeframe to utilise available funding. The Department acknowledges that having approximately one fifth of its existing staff temporarily promoted is untenable.

3.25 At March 2019 approximately 65 per cent of temporary promotions were covering vacancies at the SO grade and below. Alongside the high reliance on agency staff, this shows considerable capacity gaps at more junior grades.

3.26 However, vacancies at more senior grades are also being filled by temporary promotions. Across the departments at March 2019, just over 20 per cent of all Grade 6 staff were temporarily promoted into post, along with just under 20 per cent of Grade 7 posts. These grades currently have the highest ratios of temporary promotions.

3.27 When a member of staff is temporarily promoted to cover a higher grade, they are expected to be sufficiently competent to take on the designated duties and responsibilities. In other words the person should be fitted for promotion to the grade into which they are to act up, even when their ability may not have been fully tested through a substantive recruitment process.

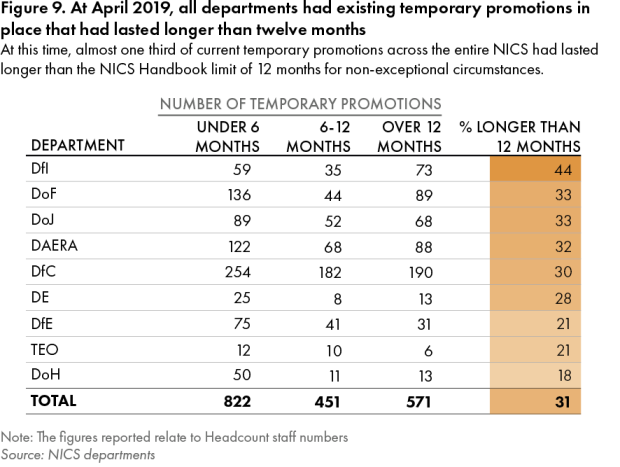

3.28 The NICS Staff Handbook suggests using a formal appointment process when awarding temporary promotions, but this is not mandatory. In addition, except for very exceptional circumstances, temporary promotions should not last longer than twelve months. Figure 9 clearly illustrates that this expectation is not being met. Information provided in departmental reports dated April 2019 showed 571 postings lasting greater than twelve months, which was almost a third of all temporary promotions at that time. In addition, all six of the departments which provided draft workforce plans to us had temporary promotions lasting in excess of four years.

3.29 The lack of a mandatory, formal appointment process, and the longevity of a significant number of temporary promotions within the NICS, is substantially increasing the risk of not placing the right people in the right posts at the right time.

Departmental workforce plans remain in development and there is no overall NICS plan

3.30 Effective workforce planning is a prerequisite for having the right number of staff with the right skills. Assumptions need to be reviewed regularly and revised to reflect changes in business needs and operational objectives.

3.31 Currently, all nine NICS departments have raised workforce planning or staff resourcing as a corporate risk, which ensures the matter receives strategic oversight. Some departments have also introduced board committees to try to ensure the effective and efficient deployment of resources.

3.32 Despite this, a formal and overarching NICS-wide workforce plan has not been developed. Prior to 2019-20, five of the nine NICS departments did not have operational workforce plans in place. This includes DoF which has central responsibility for overseeing the effective and efficient use of resources across the NICS. DoF acknowledged to us its workforce planning processes were ‘poor’. Overall, six of the nine departments acknowledged their workforce planning required some form of improvement.

3.33 In 2019, after endorsement by the NICS Board and to support departments with their workforce planning, NICSHR developed and introduced a new workforce planning template for the period 2019-2022. The template introduces a consistent approach to departmental workforce planning and establishes a baseline headcount position enabling departments to forecast staffing requirements for the period. Although six departments have progressed work on the template, three departments (DE, DfC and DfI) were unable to provide us with a draft workforce plan. This hampers the development of workforce planning, not only at departmental level but NICS-wide. Further work is therefore required.

3.34 The new workforce planning template collects workforce data on staff numbers, but it does not capture robust information on skills and experience, which would help identify capability gaps. Capability is considered further in Part Four. The NICS told us that establishing this headcount baseline is a key building block of effective workforce planning and will, in time, facilitate and enable further work on the identification of the functional skills that NICS departments require to deliver future government projects or programmes and allow NICSHR to collate an NICS-wide workforce plan.

3.35 NICSHR’s efforts to drive and encourage a more strategic workforce planning approach in the NICS are welcomed, but the process is still at a relatively early stage. To further enhance workforce planning, departments need to:

- undertake reviews of their total staffing costs, including the full costs associated with all temporary staffing solutions. This will better enable departments to set informed and realistic staff budgets and baselines;

- assess the impact of alternative working patterns on workforce plans. Line management throughout the NICS currently authorises staff requests to work alternative patterns, but with limited strategic oversight of how this impacts on workforce capacity. In 2018-19 almost 27 per cent of the NICS workforce by headcount worked alternative patterns. The DfC has the highest percentage at 32 per cent. Three of the nine departments told us that flexible working now poses problems for the operational delivery of their business, and the DfC indicated that any further requests for flexible working would be difficult to accommodate;

- consider the effect of partial retiree patterns on workforce plans. Included within the figures for alternative working patterns referenced above, almost 6 per cent of the NICS workforce by headcount were partial retirees in 2018-19. The DfC has the highest percentage at 8 per cent;

- use accurate and complete data. Three of the nine NICS departments have acknowledged this is currently not the case; and

- begin succession planning for a range of age-related retirements.

The NICS should plan for substantial numbers of NICS retirements

3.36 Monitoring age profiles at both grade and departmental level also helps inform workforce and succession planning. However, recent evidence suggests the NICS has not afforded these areas sufficient attention from a strategic or long term perspective.

3.37 Figure 10 shows the age profile from 2015 to 2019. At March 2019, only 88 NICS staff members (0.4 per cent of the workforce) were under the age of 25 years. Although not directly comparable, 13 per cent of staff in the GB Civil Service are under the age of 30 years. This under-representation of younger staff in the NICS workforce has been steadily rising over the last five years.

3.38 In contrast, almost 10,200 NICS staff (approximately 45 per cent) were aged over 50 years, compared to 40 per cent in the GB Civil Service.

3.39 This imbalance is extremely concerning but not surprising given the embargo on external recruitment in the NICS between November 2014 and April 2016 and subsequent pressures on budgets (paragraph 2.8).

3.40 At workforce grade level, the situation is particularly acute in the SCS, with over 80 per cent of staff aged over 50 years. Middle management grades from SO to Grade 6 also present a concern, with 50 per cent to 72 per cent of staff respectively being over 50 years. The number of potential retirements over the next ten years, coupled with the level of temporary promotions at these grades (paragraph 3.26), present inevitable challenges for the NICS and further highlight the need for improved workforce and succession planning. In addition, over 61 per cent of the Industrial workforce is aged over 50 years.

3.41 The staffing age profile also requires attention in some individual NICS departments (Appendix 5). Whilst DoF has the best balanced workforce in terms of age, with just over a third of its staff above 50 years, more than half the workforce is aged over 50 years in four other departments (DE, DOH, DfI and TEO). The DE has the most obvious need for workforce and succession planning, with 55 per cent of staff aged over 50 years. There are shorter term challenges in both the DfI and TEO, where more than 14 per cent of their workforce is already over the recognised pension scheme age of 60 years. As a larger department, the DfI currently has 452 staff aged 60 years or over. However, we recognise that recent external recruitment competitions in 2019 and 2020, which ultimately intend to appoint approximately 1,400 staff to the AO, SO and DP grades along with work to expand NICS apprentices, will contribute to rebalancing the workforce age profile.

3.42 If the NICS is to succeed in building workforce capacity to address vacancy management, the use of temporary staffing solutions and the NICS age profile, further external recruitment activity in the foreseeable future will be necessary.

Significant scope exists to improve NICS recruitment procedures

3.43 The NICS departments told us that significant scope exists for improving the effectiveness of current NICS recruitment processes. Figure 11 summarises the views expressed by departments.

The NICS has struggled to accurately estimate demand for recruitment competitions and the overall process is too lengthy

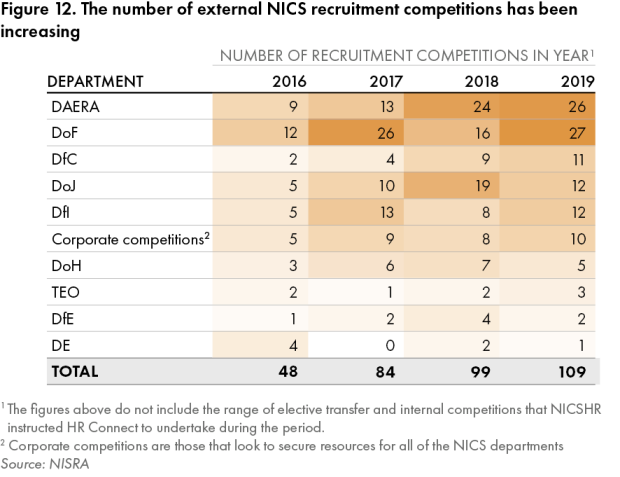

3.44 Since the recruitment embargo ended in April 2016, a significant number of external recruitment competitions have been held across the NICS (Figure 12). In 2016, 48 competitions were held. This increased to 109 in 2019.

3.45 Given our observations that further recruitment to the NICS is likely (paragraph 3.42), the processes around this must be fit for purpose and able to effectively meet demand.

3.46 Our engagement with stakeholders highlighted weaknesses with:

- NICS departments underestimating required staff numbers. This results in insufficient recruitment competitions being held and appointment lists being exhausted quickly, often before demand is fully met. In four of the six draft 2019-22 departmental workforce plans we reviewed, supply for various general service staffing grades had been exhausted; and

- the process being largely reactive, with vacancies sometimes not notified by line management until a competition is launched, and suggestions that manipulation or “gaming” of appointment lists also takes place.

3.47 Seven of the nine departments disagreed with the statement that “time taken to recruit and assign successful internal or external candidates to a post is satisfactory”, with one strongly disagreeing (Figure 11). In 2018, NICSHR engaged with stakeholders on a variety of issues, including the length of time taken to complete recruitment competitions. It highlighted delays in the process, finding that it could take up to twenty weeks, and sometimes even longer, to identify successful candidates. This did not include time taken to appoint them to a post. Our own stakeholder discussions further confirmed concerns around this area, highlighting an external recruitment exercise for Assistant Statistician which took approximately ten months from the business case being completed until the first successful candidates took up post. NICSHR told us this recruitment exercise took longer than anticipated as interviews were scheduled over a longer period than normal to accommodate graduate applicants, and NISRA experienced delays getting funding and headcount approvals. NICSHR have also informed us of improvements made in parts of the overall process in recent external competitions. However, we have been unable to critically evaluate how these have impacted on the length of time taken to place successful candidates in post due to the effect Covid-19 has had on finalising these competitions.

3.48 Lengthy recruitment processes can result in:

- lower number and quality of candidates (especially if application forms and processes are lengthy or overly arduous);

- preferred candidates with multiple offers sometimes choosing other positions that offer better terms and conditions of employment;

- candidates potentially forming negative views of the NICS, making it harder to recruit in the future; and

- staffing needs changing by the time the process is completed.

3.49 Given the importance of this area in helping the NICS maximise its workforce capacity, we are surprised information is not collated on how long it takes to complete recruitment competitions and that targets have not been set to monitor performance. Under these current circumstances, no incentive exists to drive improvement in performance. We are also surprised that recruitment is not a continuous activity for certain grades in an organisation the size of the NICS as this would help with the continuous supply of staff (paragraph 3.46).

3.50 This part of the report identifies a range of issues which require attention to better align NICS capacity with operational requirements. To achieve this, work and significant investment will be required to improve relevant processes and functions, and transformation will need to be delivered at a steady pace to enable timely progress. However, if the NICS can successfully address key strategic issues, such as reducing sickness absence, substantively filling vacancies, and improving its workforce planning and recruitment processes, this will help build a more sustainable workforce and reduce reliance on temporary staffing solutions. Making these necessary improvements will then allow the NICS to focus more on the skills, performance and capability of staff.

3.51 Part Four deals with capability in the NICS.

Part Four: A strong focus is required on building NICS workforce capability

Recruitment processes should focus on candidates’ skills and experience to better target the right people for the right posts