List of abbreviations

AME Annually Managed Expenditure

C&AG Comptroller and Auditor General

CDEL Capital Departmental Expenditure Limit

DoF Department of Finance

DEL Departmental Expenditure Limit

DoF Department of Finance

DEL Departmental Expenditure Limit

EA Education Authority

ISNI Investment Strategy for Northern Ireland

NI Northern Ireland

NIAO Northern Ireland Audit Office

NICS Northern Ireland Civil Service

OECD Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development

PfG Programme for Government

PPP Public Private Partnerships

PSNI Police Service of Northern Ireland

PSIAS Public Sector Internal Audit Standards

RDEL Resource Departmental Expenditure Limit

RoFP Review of the Financial Process

RRI Reinvestment and Reform Initiative

SIB Strategic Investment Board

SAI Supreme Audit Institution

SSEs Spring Supplementary Estimates

TEO The Executive Office

UK United Kingdom

Executive Summary

1. When dealing with limited public funds, the budgetary process which determines how they will be allocated and controlled is a critical process for all governments, including the Northern Ireland Executive (the Executive). With the economic and societal challenges created by the COVID-19 pandemic, never has it been more important to ensure that public money is being managed and spent well.

2. This report outlines key elements in the budget process operating in Northern Ireland (NI) and compares it to international good practice contained within the Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development1 (OECD) Principles of Budgetary Governance. Our review identified a number of areas where work is needed for the process to more fully comply with this good practice. Issues identified included:

- the use of single-year budgets, albeit that multi-year budgets are only possible when multi-year settlements are notified by HM Treasury;

- the restricted opportunity for the NI Assembly (the Assembly) and its committees to debate the draft budget and any in-year re-allocations2;

- not always having sufficiently detailed information available to aid Assembly scrutiny;

- budget information not being easy for non-finance professionals to understand;

- the need for a clearer linkage between budget allocations and the outcomes identified in the Programme for Government (PfG); and

- the need for greater synchronisation between the budget process and the process for establishing the capital investment strategy.

3. Previous Northern Ireland Audit Office (NIAO) reports, such as Major Capital Projects, Capacity and Capability in the NI Civil Service, and the Renewable Heat Scheme, have identified issues relating to the budgetary process. References to these within this report illustrates that getting the budgetary process right is a fundamental stepping stone to ensuring economy, efficiency and effectiveness in the delivery of public services.

4. There is an opportunity to build and improve on the current process to make it more accessible to citizens and to members of the Assembly, and to make it as effective and efficient as possible.

Part One: The budget process approves and funds public services in Northern Ireland

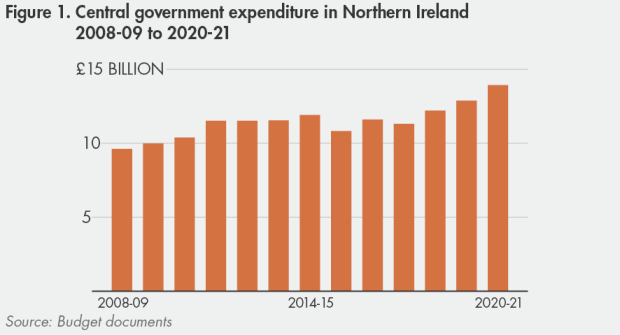

1.1 In Northern Ireland (NI), the Department of Finance (DoF) has responsibility for coordinating and collating departmental bids for funding, and for publishing the NI central government budget. This budget funds approximately £14 billion of government goods and services each year. Since the restoration of devolved government in 2007, this has amounted to approximately £162 billion of funding (see Figure 1).

1.2 The United Kingdom (UK) government funds NI through the Northern Ireland Office and the region operates within the UK’s fiscal limits. The transfer of funds from Westminster is often referred to as the Block Grant. The budgets for UK devolved administrations, including NI, are derived largely on a population based share of the funding provided for comparable English public services. This calculation is known as the Barnett Formula.

1.3 Public Expenditure is split between Annually Managed Expenditure (AME) and Departmental Expenditure Limits (DEL). AME funds expenditure which is difficult to forecast across a number of years, such as pensions and social security benefits. The AME funding is financed by HM Treasury and is managed on a yearly basis. Remaining expenditure can generally be controlled by departments and is managed within two main DEL budgets. The Resource DEL budget (RDEL) funds day-to-day running and administration costs and the Capital DEL budget (CDEL) funds investment in public assets, such as roads and IT equipment that will provide benefits over a number of years.

1.4 There are rules restricting the transfer of elements from one part of the budget to another. Once a DEL budget has been agreed for NI by HM Treasury, it is then up to the Executive to determine how the majority of these funds, should be allocated across the NI departments. It does this by producing budget documents outlining the Executive’s spending plans over a period of time, either relating to a single year or to multiple years.

1.5 In addition to the funding received from the UK government the Executive also obtains funding through domestic and non-domestic regional rates, the European Union and other charges for services. The income streams available to fund the Executive’s activities are, however, limited.

Part Two: Budgets have been set for the medium term and annually

2.1 Since 2008, two multi-year budgets (2008-11 and 2011-15) and two single-year budgets (2015-16 and 2016-17) have been set. After the collapse of the Assembly and NI Executive in January 2017, the Secretary of State set three single-year budgets. The restored NI Executive then set a further single-year budget for 2020-21. This report considers the process followed for setting these budgets.

2.2 By its nature the budgetary process is complex, and uses a considerable amount of terminology. However, at its heart any budgetary process is simply trying to establish how much can be spent, on what, and when, with limited public funds. There should be a clear link to the overall goals the Executive is trying to achieve so that citizens can have confidence that public money is being spent appropriately. A budget is therefore a key component of a government’s plans.

2.3 The Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development (OECD) Principles of Budgetary Governance provide an overview of international good practice for all areas of budget activity, from setting budgets to reviewing what was spent. They also provide practical guidance to assist with the design, implementation and improvement of budgeting systems. Whilst they are mainly relevant to a national government, most principles are also relevant to budget setting processes within devolved regions such as NI. The principles are laid out in Appendix 1. References to parliament in the principles should be read as referring to the Assembly and references to government as referring to the Executive.

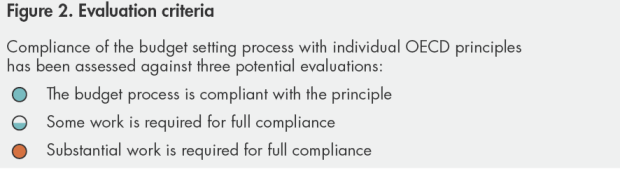

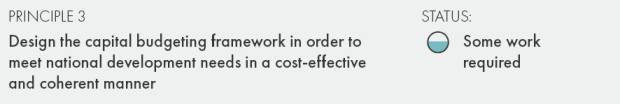

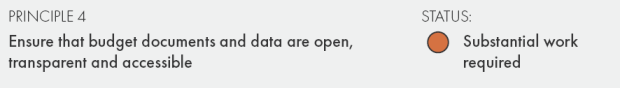

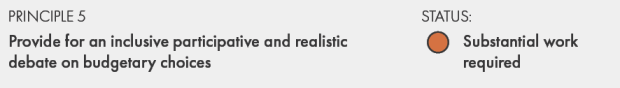

2.4 This report assesses the degree to which DoF’s budget setting process since 2008 complies with best practice contained in the OECD 2014 Principles of Budgetary Governance (see Figure 2).

Part Three: Comparison of NI’s budgetary process to the OECD’s Ten Principles of Budgetary Governance

The NI Executive’s ability to set fiscal policy is limited

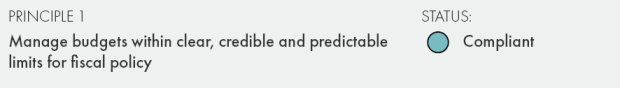

3.1 As a devolved administration NI has limited ability to set its own fiscal policy and raise taxes, therefore only certain elements of Principle 1 are applicable. The OECD guidance notes that as a minimum a government should commit to pursuing a sound, sustainable fiscal policy. In the New Decade, New Approach deal the NI Executive committed to delivering a balanced budget for NI and to take steps to put its finances on a sustainable footing. Should the newly formed Fiscal Commission for NI recommend any further amendments to tax raising powers, a formal commitment to a sound, sustainable fiscal policy should be considered, similar to that provided by the Scottish Government. Recommendations made by the Fiscal Commission will require agreement from the Executive and, if appropriate, the UK Government before implementation can proceed.

There is limited evidence of budgetary alignment with multi-year planning and goal-setting

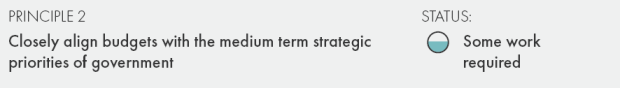

3.2 Whilst the first two budgets (2008-11 and 2011-15) were multi-year budgets, since then budgets have been annual in nature. There were various reasons for annual budgets over the last six years, for example the 2015-16 budget was set as a single-year budget since it was the last year of the UK Spending Review.

3.3 The short-term nature of annual budgets creates difficulties for future planning and innovation across the public sector. The absence of a medium-term dimension to financial planning and prioritisation has been the subject of significant criticism, e.g. the NIAO report on Capacity and Capability in the NI Civil Service noted that ”annual budget-setting ....hampered longer term financial and workforce planning.”

3.4 In its report on health funding, the NI Affairs Committee noted that:

- “Short-term budgets are having a particularly negative impact on social care, with year-on-year uncertainty impeding the ability of providers to plan for the future and develop service innovations.”

- “Three-year minimum budget allocations are needed for the Department of Health. This would facilitate the Department moving towards a minimum five-year partnership model with community and voluntary providers in which commissioning and investment are based on progress towards agreed outcomes.”

3.5 Undoubtedly the COVID-19 pandemic has created uncertainty for public finances and was a key focus in the UK Government’s 2020 Spending Review, which only related to a single year - 2021-22. Northern Ireland’s Minister of Finance expressed disappointment over the short-term nature of the UK spending plans because they constrained DoF’s ability to set a multi-year budget. While single-year budgets may sometimes be necessary, good practice suggests that the aim nonetheless should be to move to multi-year budgets as soon as possible. The New Decade New Approach agreement included a commitment to using multi-year budgets where the UK Government has provided multi-year funding.

3.6 In NI, the DoF fulfils the function of the Central Budgetary Authority and The Executive Office (TEO) fulfils other functions at the centre of government. Responsibility for coordinating the development of the Executive’s Programme for Government (PfG), which sets out its goals for the future, and for monitoring and reporting on the Programme’s delivery, rests with the TEO. A PfG was published in 2011 for 2011-15. Although a draft PfG was prepared following the May 2016 Assembly election based on an outcomes focused approach, it had not been agreed before the institutions collapsed in January 2017. An Outcomes Delivery Plan was subsequently developed by the Northern Ireland Civil Service (NICS) Board to provide a basis for the NICS strategic business planning until a new Executive was formed in January 2020. Further details were provided in underlying action plans to explain what policies and programmes would be used to deliver the planned outcomes.

3.7 The Committee for Finance and Personnel’s report into the 2008-11 budget process recommended that there should be closer alignment between the PfG and budget documents. The TEO advised that work on a PfG for the new Executive commenced in January 2020 but the COVID-19 pandemic has impacted on its finalisation. Work on the PfG resumed in October 2020, and a public consultation has recently been concluded to inform the design and content of a new PfG Outcomes Framework. In future years the TEO and DoF plan for PfGs to be finalised before the budget is determined and for there always to be a clear link between the two. This was not possible for Budget 2020-21 as no PfG was in place at the time the budget had to be determined. A new online portal is planned to allow citizens to drill down from the PfG to related documents providing detailed delivery plans and outlining key priorities.

There is little alignment between the capital investment strategy, budgets, and the medium-term fiscal plan

3.8 Capital budgeting in NI is set within the framework of the Investment Strategy for NI (ISNI). The Strategic Investment Board (SIB), an arm’s length body of the TEO, is responsible for the creation and review of the ISNI. It also acts in an advisory role to the Executive, in the planning, prioritisation, funding, borrowing and implementation of major capital projects. A number of parties are involved in the evaluation of decisions to invest in capital projects, including DoF economists, the SIB and departments themselves. Reviews conducted by the SIB and the OECD identified weaknesses in the system for managing major capital projects, leading to an NIAO Major Capital Projects December 2019. The report noted previous findings that “the system as a whole is not fit for purpose”, showed that several projects had budget overruns, and indicated that project prioritisation needed to be improved. Much work is therefore needed in this area.

3.9 During this period two investment strategies were established, for 2008-11 and 2011-21. Whilst the SIB is responsible for the creation and review of the ISNI, it is the DoF which has responsibility for financing it, through bids for capital funding which are made on a case by case basis by departments. The development of the ISNI is currently undertaken independently from the budget process, since the timing of these processes is not synchronised. This will only be possible once multi-year budgets are in place, tying in with the medium-term nature of the ISNI. There is, nonetheless, a degree of correlation since:

- departments will know of any approved budgets in place when they engage with the SIB to develop the ISNI; and

- capital budgets are recorded in a way that links back to elements within the ISNI and the SIB receives reports of actual expenditure against the ISNI after the year end.

3.10 Co-ordination is key, but since a medium-term fiscal plan is not currently in place within NI, the ISNI cannot be integrated with it. This is not always within the Executive’s control since a multi-year Spending Review settlement from HM Treasury would need to be in place to allow a medium-term fiscal plan to be produced. The SIB advises that the next ISNI will provide a robust strategic framework to guide future decisions on investment prioritisation, delivery planning and capital financing/funding over the medium to long term and will inform and integrate with a medium term fiscal plan. Co-ordination of other aspects have been assisted by Community Planning, which has provided an opportunity for central government and local government to coordinate with each other to ensure better outcomes for citizens, despite having different budget setting processes.

Budget information lacks clarity, with few links to proposed Programme for Government outcomes

3.11 Budget documents are available online and in a range of formats, which is in line with good practice. However, the budget document can be difficult for anyone other than a financial professional to understand, given the amount of terminology it contains. The year-end accounts of public bodies, which report on how they spent the public money allocated to them, are also complex. This was highlighted as an issue by the then Chair of the Westminster Public Accounts Committee when she stated:

“I think it’s an important document, but it is pretty impenetrable, and I think the Treasury should set about trying to simplify it……… I think it should be simple, I think everyone should comply, I think it should be completed more quickly, and I think Treasury should start producing numbers and use those numbers to then decide what we do in the future”

3.12 Expenditure allocations are made at a ‘Spending Area’ level, a broad term with millions of pounds of funding assigned to them. Details of a cross-section of these allocations are shown in Figure 3. While the descriptions used have improved during the 13 year period under review, the high level nature of these terms makes it difficult for readers of financial statements to identity the individual policies and programmes funded, or how any income is generated.

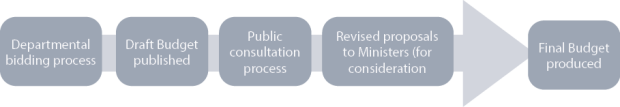

There is limited debate on budgetary choices

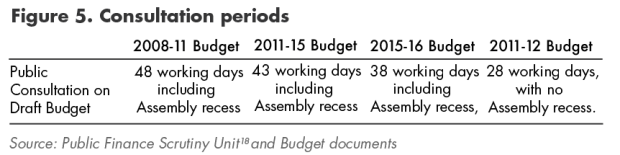

3.13 The budget process between 2008 and 2016 is shown in Figure 4. Due to a range of issues, including the collapse of the Assembly in January 2017, the other five budgets considered in this report have seen the removal of the draft budget and public consultation stages. This was re-introduced for the 2021-22 budget. However, the time available for stakeholder engagement on budgetary choices has steadily reduced (see Figure 5). The Assembly and its committees should have the opportunity to engage with the budget process at all stages of the budget cycle. The timing of a UK Spending Review, will however have a direct impact on the time available for consideration of the budget.

Figure 4. NI budget process between 2008 and 2016

Source: Public Finance Scrutiny Unit

3.14 In addition to allowing time for engagement, stakeholders need to have access to detailed information in order to debate budgetary choices. The Committee for Finance and Personnel highlighted in its 2008 report that there was a “general difficulty in obtaining detailed information to enable sufficient scrutiny and prioritisation.” An Assembly Research Paper in 2017 noted that three of the nine departments did not supply budget information to their respective Assembly committee prior to the 2017-18 budget announcement as required. A fourth said that it would not be able to provide any information on the budget until after the final budget had been issued.

3.15 The Committee for Finance and Personnel recommended that a “Memorandum of Understanding” should be agreed between the Assembly and the DoF, including a timetable for the provision of budget information. Twelve years and seven budgets have now passed since this report, but this Memorandum is not yet in place. Nonetheless, this should not prevent departments effectively engaging with their respective Assembly Committees to provide sufficiently detailed, timely information to enable effective scrutiny of budget decisions, as encouraged by the DoF.

3.16 Engagement with the public is also an important element within the budgetary process, but only limited funding has been allocated under participative budgeting to date. This is a form of budgeting where local people decide how to allocate part of a public budget, and has been identified as good practice by a number of organisations, including the OECD and the World Bank. The DoF, however, advises that there is significant engagement with key stakeholder groups such as the Northern Ireland Council for Voluntary Action (NICVA), business organisations and unions.

The overview of public finances in NI can be improved

3.17 Generally the budget contains all expenditure in central government in NI. However, due to the need for the Executive’s response to the COVID-19 pandemic to be rapid and flexible, funding for this response has been taken forward largely separately from the 2020-21 Budget. Of £1.192 billion made available to the Executive by the UK government at April 2020 for its COVID-19 response, only £120 million of resource DEL and £1.3 million of capital DEL was made available through the budget process. This was due to legislative restrictions preventing the remaining funds being incorporated into the budget. Total COVID-19 funding for 2020-21 amounted to £3.3 billion. The vast majority of this funding was dealt with outside of the normal budget process, as the DoF was only notified of it after the Budget had been set, with funding being received throughout the year, and up to January 2021.

3.18 In accounting for how they have spent public money, NI central government bodies are required to use accruals accounting and budgeting, although a cash limit called the Net Cash Requirement is also approved by the Assembly. At present, differences exist between the treatment of certain items for accounting purposes, the budget process and the Estimates. An example of this would be the treatment of arm’s length bodies, such as the Police Service of Northern Ireland (PSNI). In the Department of Justice’s financial accounts, PSNI expenditure is represented by the cash grant paid to the body and this treatment also aligns to the Estimates. For budget purposes however, the net expenditure of the PSNI on an accruals basis is used when considering the overall expenditure of the Department.

3.19 A DoF programme called the Review of the Financial Process (RoFP) was set up in 2011 to better align accounting boundaries, budgets and Estimates. It was agreed by the Executive in December 2016, prior to the collapse of the Assembly. It therefore remains in its implementation phase some nine years later, with the DoF currently finalising legislation for its introduction to the Assembly. It is not clear when full implementation will be possible due to the pandemic.

3.20 At a UK level, Whole of Government Accounts are prepared, consolidating accounting information for over 9,000 public sector bodies, including central and local government bodies. Whilst these take time to prepare and audit, they provide a comprehensive picture of the UK’s public sector finances. Having an overview of long-term liabilities helps inform more effective management of fiscal risks and can help facilitate public debate. The Government Resources and Accounts Act (Northern Ireland) 2001 provides for a similar account to be produced at NI level, however the DoF advised that this would present significant challenges and this provision was never commenced. Once the RoFP has been implemented, there may be benefit in exploring the possibility of using NI information provided to HM Treasury to create a summary document of the key headline figures for long-term liabilities and commitments. This would help inform debate moving forward.

3.21 The principle also suggests that the budget document should include public programmes funded by non-traditional means such as Public Private Partnerships (PPP), for example by including details of the future payments that are due to the contractor. The 2006 NIAO report on the Reinvestment and Reform Initiative (RRI) recommended that PPP and borrowing commitments under RRI should be reported together to improve transparency. Although capital expenditure and future RRI borrowing commitments are included within the 2020-21 budget document, no information is provided on PPP commitments, and the implications for future budgets of PPP or RRI commitments could be more clearly articulated.

Funds are reallocated during the year without prior Assembly debate or approval

3.22 In NI the majority of public income and expenditure goes through the Northern Ireland Consolidated Fund. Most of the outflows from the Fund represent money transferred to individual NI departments to fund public services. Rules on the operation of this Fund are prescribed in legislation and the Fund is controlled by the DoF, subject to the Comptroller and Auditor General (C&AG) authorising payments. All payments from the Fund must have legislative authority and may either be charged to it directly by statute or voted by the Assembly each year in the Budget Acts. Payments into and out of the Fund are reported annually in the Public Income and Expenditure Account which is audited by the C&AG. There are also a few smaller funds administered and controlled by the DoF, but these are not significant.

3.23 There is some flexibility for NI departments to move funding between the detailed headings shown in the Estimates, in a process known as virement, whilst still remaining within the overall control limits voted by the Assembly. Rules over this process are controlled by the DoF, which must approve any virement requests. Refusal of approval could lead to an Excess Vote which must be reported to the Assembly. The DoF also controls a process called ‘In-Year Monitoring’ which provides the Executive with a mechanism to review its spending plans usually three times during the year – June, October and January, potentially leading to funding allocations to Spending Areas during the year in light of the most up to date information.

3.24 At each of the monitoring rounds departments, with the approval of their Minister, either:

- bid for additional funding to address in-year funding pressures;

- move funding between ‘Spending Areas’ within the previously agreed budget allocations; or

- surrender funding that is no longer required (which should be done at the earliest opportunity to ensure it can be utilised by another department).

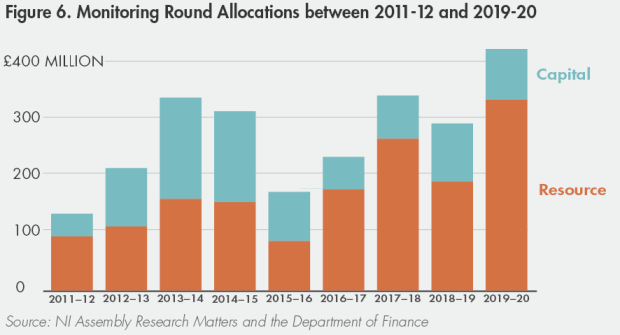

3.25 In the nine years from April 2011 to March 2020 £2.5 billion was allocated through in-year monitoring – see Figure 6.

3.26 The Assembly does not approve allocations made at the monitoring rounds; it is informed of the allocations either via an oral or written Ministerial Statement by the Minister of Finance, with Assembly Members given the opportunity to ask questions. Following the final monitoring round in January each year, the Assembly votes to approve the Spring Supplementary Estimates (SSEs) which reflect the changes made during the monitoring rounds throughout the year. Whilst there is an extensive Assembly debate prior to the approval of the SSEs, Members cannot at that point influence the allocations made, therefore the process does not fully support the Assembly in effectively challenging changes to budget allocations made during the year.

3.27 The Executive has limited ability to carry forward funding that it cannot spend from one year into the next. Under HM Treasury’s rules within the Budget Exchange scheme the Executive is only permitted to carry forward underspends of up to 0.6 per cent for Resource DEL and 1.5 per cent for Capital DEL. Underspends above the Budget Exchange limits are lost to NI. This increases the risk that time pressure to spend funds before the end of the financial year may result in funds not being spent well.

The budget process does not clearly link inputs to outcomes

3.28 Annual accounts produced by public bodies provide information on what each has spent. However in terms of overall NI expenditure, whilst some information is included within rates bills and the budget document illustrating which public services have been bought, this tends to be at a high level and does not indicate the quality and efficiency of those services. Performance information is provided in the annual accounts of public bodies, however this does not link back to the funding allocations in the budget and there is currently no report linking PfG interim outcomes to the budget used each year.

3.29 The 2020 NIAO Impact Review of Special Educational Needs noted that the Education Authority (EA) did not hold data on the outcomes for children, despite spending £312 million per annum on providing these services:

“Evidence of robust evaluation and associated outcomes is not yet available. Once it is completed the Department and the EA should be in a position to make informed decisions, focussing resources on the types of support which maximise progress and achieve the best outcomes.”

3.30 While the principle suggests that government should periodically take stock of overall expenditure and re-assess how expenditure and national priorities align, NI adopts an incremental approach to budgeting for its day-to-day expenditure. This method takes the prior year budget as its starting point, adjusting it to allow for items such as salary increments, inflation, projections for new expenditure, or fluctuations in revenue. This is a simple form of budgeting which has advantages, but also disadvantages. Since 2007, a number of reports on budgeting within NI have recommended that the Executive moves away from this approach to one that would provide a transparent link between inputs and outcomes. Nevertheless, the Executive has continued to use incremental budgets for resource expenditure. The DoF has advised that this approach reflects the nature of resource spending, which is largely recurrent in nature e.g. salary budgets. Zero-based budgeting is used, however, for capital expenditure.

3.31 In-Year Monitoring rounds provide an opportunity to review budget requirements and Executive priorities during the year, but this process could be taken further. Including PfG interim outcomes in the consideration would help to ensure funds are allocated where most required to achieve the goals set by the Executive. Under the Wellbeing of Future Generations (Wales) Act 2015 the Welsh government is required to provide an assessment of public bodies’ performance against their well-being objectives. The report explains what improvement has been achieved to the population’s well-being. This type of reporting provides accountability over the public sector’s performance against objectives.

NI has limited exposure to fiscal risks that it is responsible for managing

3.32 As a devolved administration, NI has limited exposure to fiscal risks and the amount it can borrow is prescribed by the UK government. Nonetheless, fiscal risks at a UK level can impact on the funding available for public services in NI and the Executive must therefore consider the potential impact of these risks on the services it can provide. In budget documents prior to April 2017, information was included on the amount of debt carried by NI, together with details of plans for its repayment. The 2020-21 and 2021-22 budget documents have once again included information on RRI borrowing and repayment, however it is not clear from the information provided the impact this will have on the funding available for future services.

3.33 Modelling of budget scenarios for future years is undertaken by the DoF. Given that the overall budget for NI is determined by HM Treasury and without a multi-year settlement, this is inevitably at a high level. The NI Executive also has fewer tax raising powers compared to other devolved administrations in the UK. There are some opportunities to generate additional revenues to support longer-term sustainability in the NI budget under current powers, for example, water charging. However, decisions such as these rest with the Executive and the Assembly rather than with the DoF. Consideration of potential further fiscal powers for the Executive is a key responsibility of the newly established Fiscal Commission.

There is limited quality assurance of budget forecasts, fiscal plans and budgetary implementation

3.34 Instilling confidence in a broad range of stakeholders on the quality and integrity of budgetary forecasts and fiscal plans and the Executive’s ability to manage the budget has proved problematic in NI due to two significant events during the period under review:

- In 2015-16 the Assembly initially failed to reach agreement on a balanced budget, due to issues around welfare reform. After the Stormont House Agreement was signed, however, the foundations were laid for the Executive to reach agreement on a balanced budget.

- In 2016 the NIAO reported on the Renewable Heat Incentive scheme which was introduced without appropriate cost control measures in place. The initial projected £140 million funding deficit attracted considerable adverse media coverage, and had the potential to impact on future NI budgets.

3.35 The principle also indicates that the credibility of budgeting may be enhanced through independent institutions undertaking impartial scrutiny of the budget. At a national level the Office of Budget Responsibility, created in 2010, provides independent and authoritative analysis of the UK’s public finances. The New Decade, New Approach deal contained a commitment to establish a Fiscal Council to undertake an annual assessment of the NI Executive’s plans to balance its budget. The Finance Minister announced its establishment and membership on 12 March 2021, together with plans for it to scrutinise the 2021-22 budget. A Fiscal Commission has also been established to examine and make recommendations on fiscal powers.

3.36 Having the right skills available is key to ensuring quality in the budgeting process, and finance skills in the NICS have increased substantially in the last two decades, with 388 qualified accountants and a further 116 part qualified accountants working in the NICS at April 2020. Their skills are also supplemented with economists and general service staff specialising in public expenditure. Notwithstanding this, it is vital that non-finance professionals, including MLAs, are also given the skills they need to understand and contribute to the budgetary process.

3.37 Whilst there is an opportunity for independent internal auditors to provide assurance on the budgetary processes and adequacy of budgetary processes and financial management within departments, this is not an area of key focus for internal audit.

3.38 In NI, the role of supreme audit institution (SAI) is undertaken by the C&AG and the NIAO. The OECD believes that a well-functioning SAI should deal with all aspects of financial accountability, with its audit reports feeding into the budget cycle. However, the C&AG’s remit is to audit year-end accounts and conduct studies into how economically, efficiently and effectively central government bodies have used their resources, rather than directly considering the budget process each year. Any ability to report on the budget process is also inhibited by the different basis on which budgets and accounts are compiled, which the Review of the Financial Process seeks to address.

Appendix One: OECD’s Ten Principles of Budgetary Governance

Principle 1: Manage budgets within clear, credible and predictable limits for fiscal policy, through:

- having procedures in place to support governments in effecting counter-cyclical or cyclically neutral policies, and in using resource endowments prudently;

- committing to pursue a sound and sustainable fiscal policy;

- considering whether the credibility of such a commitment can be enhanced through clear and verifiable fiscal rules or policy objectives which make it easier to understand and to anticipate the government’s fiscal policy course throughout the economic cycle, and other institutional mechanisms to provide an independent perspective in this regard;

- applying top-down budgetary management, within these clear fiscal policy objectives, to align policies with resources for each year of a medium term fiscal horizon; noting that in this context, adherents should adopt overall budget targets for each year which ensure that all elements of revenue, expenditure and broader economic policy are consistent and are managed in line with the available resources.

Principle 2: Closely align budgets with the medium-term strategic priorities of government, through:

- developing a stronger medium-term dimension in the budgeting process, beyond the traditional annual cycle;

- organising and structuring the budget allocations in a way that corresponds readily with national objectives;

- recognising the potential usefulness of a medium-term expenditure framework in setting a basis for the annual budget, in an effective manner which had real force in setting boundaries for the main categories of expenditure for each year of the medium term horizon; is fully aligned with the top-down budgetary constraints agreed by government; is grounded upon realistic forecasts for baseline expenditure (i.e. using existing policies), including a clear outline of key assumptions used; shows the correspondence with expenditure objectives and deliverables from national strategic plans; and includes sufficient institutional incentives and flexibility to ensure that expenditure boundaries are respected;

- nurturing a close working relationship between the Central Budgetary Authority and the other institutions at the centre of government (e.g. primes minister’s office, cabinet office or planning ministry), giving the inter-dependencies between the budget process and the achievement of government-wide policies;

- considering how to devise and implement regular processes for reviewing existing expenditure policies, including tax expenditures, in a manner that helps budgetary expectations to be set in line with government-wide developments.

Principle 3: Design the capital budgeting framework in order to meet national development needs in a cost-effective and coherent manner, through:

- the grounding of capital investment plans, which by their nature have an impact beyond the annual budget, in objective appraisal of economic capacity gaps, infrastructure development needs and sectoral/social priorities;

- the prudent assessment of the costs and benefits of such investments; affordability for users over the long-term, including in light of recurrent costs; relative priority among various projects; and overall value for money;

- the evaluation of investment decisions independently of the specific financing mechanism, i.e. whether through traditional capital procurement or a private model such as public-private partnership (PPP);

- the development and implementation of a national framework for supporting public investment which should address a range of factors including: adequate institutional capacity to appraise, procure and manage large capital projects; a stable legal, administrative and regularity framework; coordination of investment plans among national and sub-national levels of government; integration of capital budgeting within the overall medium-term fiscal plan of the government.

Principle 4: Ensure that budget documents and data are open, transparent and accessible, through:

- the availability of clear factual budget reports which should inform the key stages of policy formulation, consideration and debate, as well as implementation and review;

- the presentation of budgetary information in comparable format before the final budget is adopted, providing enough time for effective discussion and debate on policy choices (e.g. a draft budget or a pre-budget report), during the implementation phase (e.g. a mid-year budget report) and after the end of the budget year (e.g. an end-year report) to promote effective decision-making, accountability and oversight;

- the publication of all budget reports fully, promptly and routinely, and in a way that is accessible to citizens, civil society organisation and other stakeholders;

- the clear presentation and explanation of the impact of budget measures, whether to do with tax or expenditure, noting that a “citizen’s budget” or budget summary, in a standard and user friendly format, is one way of achieving this objective;

- the design and use of budget data to facilitate and support other important government objectives such as open government, integrity, programme evaluation and policy coordination across national and sub-national levels of government.

Principle 5: Provide for an inclusive, participative and realistic debate on budgetary choices, by:

- offering opportunities for the parliament and its committees to engage with the budget process at all key stages of the budget cycle, both ex ante and ex post as appropriate;

- facilitating the engagement of parliaments, citizens and civil society organisations in a realistic debate about key priorities, trade-offs, opportunity costs and value for money;

- providing clarity about the relative costs and benefits of the wide range of public expenditure programmes and tax expenditures;

- ensuring that all major decisions in these areas are handled within the context of the budget process.

Principle 6: Present a comprehensive, accurate and reliable account of the public finances, through:

- accounting comprehensively and correctly in the budget document for all expenditures and revenues of the national government, with no figures omitted or hidden (although restrictions may apply for certain national security or other legitimate purposes), and with laws, rules or declarations that ensure budget sincerity and constrain the use of “off-budget” fiscal mechanisms;

- presenting a full national overview of the public finances – encompassing central and sub-national levels of government, and a perspective on the whole public sector – as an essential context for a debate on budgetary choices;

- accounting in a manner that shows the full financial costs and benefits of budget decisions, including the impact upon financial assets and liabilities; noting that accruals budgeting and reporting, which correspond broadly with private sector accounting norms, routinely show these costs and benefits; where traditional cash budgeting is used, supplementary information is needed; where accruals methodology is used, the cash statement should also be used to monitor and manage the finding of government operations from year to year;

- including and explaining public programmes that are funded through non-traditional means – e.g. PPPs – in the context of the budget documentation, even where (for accounting reasons) they may not directly affect the public finances within the time frame of the budget document.

Principle 7: Actively plan, manage and monitor the execution of the budget, through:

- the full and faithful implementation by public bodies of the budget allocations, once authorised by parliament with oversight throughout the year by the Central Budgetary Authority and line ministries as appropriate;

- the prudent profiling, control and monitoring of cash disbursements, and clear regulation of the roles, responsibilities and authorisations of each institution and accountable person;

- the use of a single, centrally controlled treasury fund for all public revenues and expenditure is an effective mechanism for exercising such regulation and control, with the use of special-purpose funds, and ear-marking of revenues for particular purposes, kept to a minimum;

- allowing some limited flexibility, within the scope of parliamentary authorisations, for ministries and agencies to allocate funds throughout the year in the interests of effective management and value-for-money, consistent with the broad purpose of the allocation;

- streamlining of very detailed line items, or devolved authorisation for managing reallocations among line items (virement), in the interests of facilitating such flexibility; noting that more significant reallocations, e.g. involving large sums or new purposes, should require new parliamentary authorisation;

- the preparation and scrutiny of budget execution reports, including in-year and audited year-end reports are fundamental to accountability and which, if well-planned and designed, can yield useful messages on performance and value-for-money to inform future budget allocations.

Principle 8: Ensure that performance, evaluation and value for money are integral to the budget process, in particular through:

- helping parliament and citizens to understand not just what is spent, but what is being bought on behalf of citizens, i.e. what public services are actually being delivered, to what standards of quality and with what levels of efficiency;

- routinely presenting performance information in a way which informs, and provides useful context for, the financial allocations in the budget report; noting that such information should clarify, and not obscure or impede, accountability and oversight;

- using performance information, therefore, which is limited to a small number of relevant indicators for each policy programme or area; clear and easily understood; allows for tracking of results against targets and for comparison with international and other benchmarks; makes clear the link with government-wide strategic objectives;

- evaluating and reviewing expenditure programmes (including associated staffing resources as well as tax expenditures) in a manner that is objective, routine and regular, to inform resource allocation and re-prioritisation both within line ministries and across government as a whole;

- ensuring the availability of high-quality (i.e. relevant, consistent, comprehensive and comparable) performance and evaluation information to facilitate an evidence-based review;

- conducting routine and open ex ante evaluations of all substantive new policy proposals to assess coherence with national priorities, clarity of objectives, and anticipate costs and benefits;

- taking stock, periodically, of overall expenditure (including taxation expenditure) and reassessing its alignment with fiscal objectives and national priorities, taking account of the results of evaluations; noting that for such a comprehensive review to be effective, it must be responsive to the practical needs of government as a whole.

Principle 9: Identify, assess and manage prudently longer-term sustainability and other fiscal risks, through:

- applying mechanisms to promote the resilience of budgetary plans and to mitigate the potential impact of fiscal risks, and thereby promoting a stable development of public finances;

- clearly identifying, classifying by type, explaining and, as far as is possible, quantifying fiscal risks, including contingent liabilities, so as to inform consideration and debate about the appropriate fiscal policy course adopted in the budget;

- making explicit the mechanisms for managing these risks and reporting in the context of the annual budget;

- publishing a report on long-term sustainability of the public finances, regularly enough to make an effective contribution to public and political discussion on this subject, with the presentation and consideration of its policy messages, both near-term and longer-term in the budgetary context.

Principle 10: Promote the integrity and quality of budgetary forecasts, fiscal plans and budgetary implementation through rigorous quality assurance including independent audit, and in particular through:

- investing continually in the skills and capacity of staff to perform their roles effectively – whether in the Central Budget Authority, line ministries or other institutions – taking into account national and international experiences, practices and standards;

- considering how the credibility of national budgeting – including the professional objectivity of economic forecasting, adherence to fiscal rules, longer-term sustainability and handling of fiscal risks – may also be supported through independent fiscal institutions or other structured, institutional processes for allowing impartial scrutiny of, and input to, government budgeting;

- acknowledging and facilitating the role of independent audit as an essential safeguard for the quality and integrity of budget processes and financial management within all ministries and public agencies;

- supporting the supreme audit institution (SAI) in its role of dealing authoritatively with all aspects of financial accountability, including through the publication of its audit reports in a manner that is timely and relevant for the budget cycle;

- promoting the role of both internal and external control systems in auditing the cost-effectiveness of individual programmes and governance frameworks more generally.