Abbreviations

DAERA Department for Agriculture, Environment and Rural Affairs

DE Department of Education

DfC Department for Communities

DfE Department for the Economy

DfI Department for Infrastructure

DoF Department of Finance

DoH Department of Health

DoJ Department of Justice

EAP Employee Assistance Programme

HR Human Resources

NICE National Institute for Health and Care Excellence

NICS Northern Ireland Civil Service

NISRA Northern Ireland Statistics and Research Agency

OHS Occupational Health Services

PPMA Public Sector People Managers Association

TEO The Executive Office

USEL Ulster Supported Employment Limited

Executive Summary

Sickness absence levels are consistently high and have a significant impact on public service delivery

1. Almost one quarter of the Northern Ireland workforce is employed by the public sector. When significant numbers of staff are unable to work because of sickness, the impact on service delivery including delays, increased workloads, lost productivity and additional financial costs to cover absences is likely to be considerable.

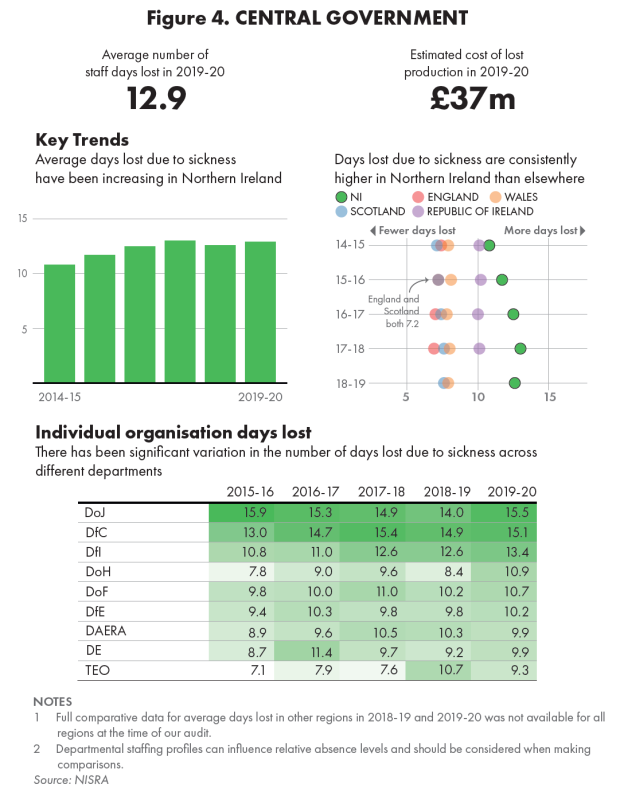

2. Almost 273,000 working days were lost to sickness absence in the Northern Ireland Civil Service (NICS) in 2019-20. This equates to almost 13 days lost for each employee, an increase of over 10 per cent in the last five years. It is estimated that NICS sickness absence cost almost £37 million in 2019-20, bringing the total cost of lost production in the last five years to almost £169 million. NICS sickness absence levels are almost double that of the Civil Service in England, and Northern Ireland is the only region in the UK where civil service sickness levels have increased significantly over the last five years.

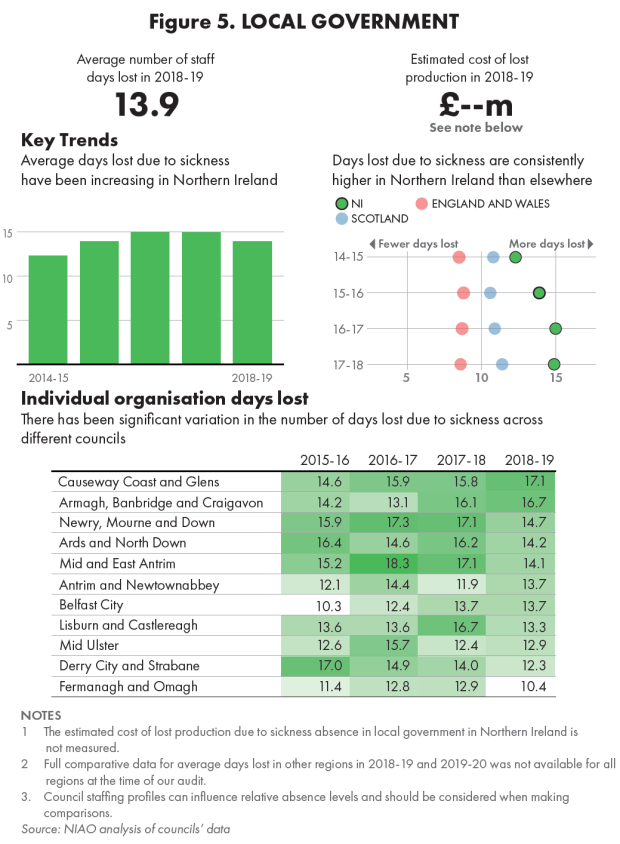

3. Local councils experience even higher levels of sickness absence, at almost 14 days per employee in 2018-19. There is a significant variation in absence rates between different councils, ranging from ten to seventeen days. Sickness absence in NI councils consistently ranks as the highest in the UK, with no indication of significant improvement. Councils do not routinely measure the overall cost of lost production due to sickness absence. In our view, it is essential that organisations understand the financial impact of high levels of sickness absence.

There are a number of challenges in managing attendance

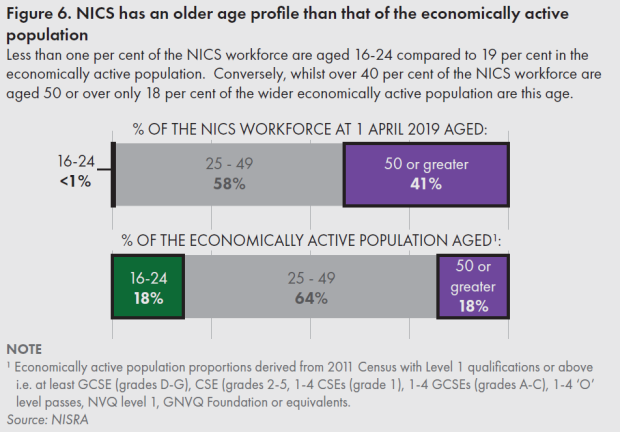

4. Over 40 per cent of civil servants are over the age of 50 compared to 18 per cent of the economically active population. Whilst older employees are not off sick more often than their colleagues, when they are absent, it tends to be to be for longer periods of time. Organisations will need to consider how best to support the health and wellbeing of older employees in the future.

5. Mental health conditions are a prominent cause of long-term sickness absence in NICS. Over 102,000 working days were lost due to anxiety, stress and depression in 2019-20. Mental health conditions can lead to longer periods of sickness absence. The average duration of an absence spell due to one of these mental health conditions was over 41 days. Organisations we spoke to recognise the importance of mental health awareness and support in relation to managing attendance and this will continue to be an important area of focus in the future.

6. Long-term absences account for over three quarters of the working days lost in NICS and almost two thirds of the days lost in local councils. One in eight staff in NICS had a long-term sickness absence in 2019-20 and the average length of long-term absence was 63 days, the equivalent of the loss of 951 full-time staff for an entire year. Reducing the level of long-term sickness absence in the public sector would have a significant impact on both the costs and impact of sickness absence.

Key principles in managing attendance should be applied across the public sector

7. The prevalence of sickness absence in the public sector indicates that a concerted effort is required to reduce the level of absence and develop a consistent approach to managing attendance. We have identified key principles in attendance management that are consistent across the public sector.

Recommendations

1. Public sector organisations should regularly review the effectiveness of sickness absence policies and procedures to ensure that they are being implemented fairly and consistently and that they are fit for purpose. Organisations which have more than one sickness absence policy in operation should implement a single policy as soon as possible.

2. Organisations should ensure that all those with line management responsibility receive regular training on sickness absence policies and procedures.

3. Health and wellbeing initiatives must be backed by strong leadership and visible support from leadership of the organisation. We recommend that sickness absence statistics are regularly considered by senior management at board level. As part of this process, organisations should consider appointing a member of the senior leadership team to be an advocate for promoting good attendance.

4. Organisations should monitor feedback and data to further improve Employee Assistance Programmes and ensure that they are as responsive as possible to employee needs.

5. Internal communication is an important factor in the successful management of long-term sickness absence. Organisations should develop protocols for specialist services such as OHS, HR professionals and line managers to work closely together.

6. Organisations should ensure that employees experiencing serious conditions are referred to appropriate specialist health services in a timely manner.

7. All organisations should have a formal inefficiency procedure to deal with unacceptable levels of absence, and senior leadership teams should ensure that these are implemented when required.

8. In order to monitor and improve sickness absence levels it is essential to have accurate, timely and accessible information. Organisations should collect sufficient data to enable sickness absence reasons and changing trends to be monitored. Monitoring should include an attempt to calculate, analyse and report the costs of sickness absence if this is not already done.

9. Consideration should be given to establishing arrangements to allow for the sharing of good practice from across the public sector. Central government organisations should also review the information available to them from NISRA and consider benchmarking their performance, where appropriate. Organisations that do not currently make detailed sickness absence information publicly available should be encouraged to do so.

Part One: Introduction

Almost one quarter of the total workforce in Northern Ireland is employed by the public sector

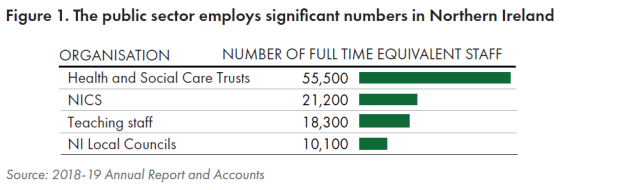

1.1 The health and wellbeing of employees is fundamental to the effective delivery of public services. Northern Ireland public sector employment per head of population is higher than any other region in the UK. Almost 210,000 people are employed by the public sector in Northern Ireland, representing 24 per cent of the total workforce, compared to just over 16 per cent across the whole of the UK (see Figure 1).

1.2 Public sector employment encompasses many diverse roles including nurses, teachers, prison officers, refuse collectors and administrative staff. Working environments also differ widely, with a high proportion of staff in manual and public facing roles. This diversity makes it difficult to make direct comparisons between organisations. High level, direct comparison between sectors is also made difficult by the different measures applied by each sector in calculating sickness absence levels. Care should therefore be taken in making such comparisons, however there are several key principles in managing attendance that are consistent across all sectors.

High levels of absenteeism have a significant impact on public service delivery

1.3 Taking into consideration the significant numbers involved, when staff are unable to work because of illness, the productivity and cost effectiveness of the public sector is likely to be significantly affected. High levels of sickness absence can result in a range of impacts:

- Predictable patterns of attendance and a full staff complement are essential to managing workflow and ensuring the effective and timely delivery of public services;

- Attempting to maintain service levels during periods of staff absence may create an additional burden on remaining staff through reallocation of work and increased workloads and therefore can have a negative impact on staff welfare; and

- There are considerable financial costs associated with high levels of sickness absence, including lost productivity and the costs of temporary staff or promotions required to cover absences.

NIAO has previously reported on sickness absence in the public sector

1.4 In 2013, NIAO reported on sickness absence in the Northern Ireland public sector. This report identified sickness absence levels across the Northern Ireland Civil Service (NICS), the health and social care trusts and the education sector and provided an analysis of how information is monitored across the three sectors. Our report found that there was a generally downwards trend in sickness absence in the period under review, however levels varied between sectors.

1.5 We reported that long-term sickness absence accounted for the majority of absence and that mental health conditions were the main cause of sickness absence across all sectors. One of our recommendations stated that “in order to sustain improvements in sickness absence…it is important that attention remains focused on reductions in long-term sickness and absences where the cause is mental health related.”

1.6 The 2013 report demonstrated that in all comparable areas, sickness absence levels in the Northern Ireland public sector were higher than elsewhere in the UK. The report highlighted the significant cost of sickness absence on the public sector, including £30 million of lost production costs in NICS. We considered that there was significant scope for reducing these costs if sickness absence rates could be lowered, particularly if the levels fell to those in Great Britain.

1.7 Since our 2013 report, which analysed statistics from the 2010-11 year, sickness absence levels have deteriorated across all sectors:

- NICS sickness absence levels have increased from 10.7 days to 12.9 days per employee, and lost production costs increased to £36.6 million in 2019-20.

- Teachers’ sickness absence has increased from 7.3 days to 9.5 days per employee.

- Absence rates in the six health and social care trusts have increased from an average of five and half per cent to over seven per cent.

1.8 Although our 2013 report did not include an analysis of local government sickness absence rates, these have also increased in recent years. Our analysis shows that almost 14 days were lost per employee in local councils in 2018-19, representing an increase of 13 per cent since 2014-15.

1.9 With levels of public sector sickness absence remaining consistently high and showing little sign of improvement, there is an opportunity to provide an update on the 2013 report, extend coverage to local government and identify guidance on managing attendance. NIAO’s role gives us a “bird’s eye” perspective across the public sector and has allowed us to analyse information from both central and local government. We are also uniquely placed to identify key principles that are consistent across the sector and engage with public sector leaders to encourage best practice in managing attendance.

Scope

1.10 This report provides an overview of sickness absence levels across the nine central government departments and eleven local councils in Northern Ireland. We did not assess the appropriateness of the policies in place in the various organisations. We met with stakeholders directly involved in managing attendance across the public sector including key staff at NICSHR, Heads of HR from three local councils and senior management within NICS departments.

1.11 Part Two provides an overview of sickness absence across central and local government in Northern Ireland. Part Three sets out key principles for managing attendance that are consistent across the public sector.

1.12 Work on this report commenced prior to the outbreak of COVID-19 and involved a review of the available sickness absence statistics at that point, therefore it does not include any assessment of the effect of the pandemic on absence levels. However, some of the principles identified will be relevant to organisations’ medium-term response to the impact of COVID-19 on their employees.

Conclusions

1.13 We heard about projects and initiatives that have been implemented to attempt to address the significant levels of sickness absence in a number of public sector organisations. We acknowledge that good work is being done and details of some of these initiatives are included in Part Three of this report. However, in our view, there is more progress to be made on managing attendance in the public sector including a need for a more strategic, joined up approach, a particular focus on reducing long-term absence and opportunities for organisations to share good practice.

Part Two: An overview of sickness absence in the Northern Ireland public sector

Rates of sickness absence in the Northern Ireland Civil Service are higher than anywhere else in the UK

2.1 In 2019-20 the Northern Ireland Statistics and Research Agency (NISRA) reported that 12.9 working days per employee per year were lost on average in NICS. This figure has increased by more than 25 per cent since 2013-14 and represents almost 273,000 working days lost in one year. NISRA estimated that lost production costs due to sickness absence in 2019-20 amounted to almost £37 million (see Figure 4).

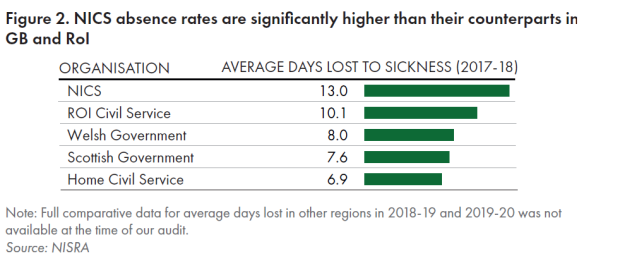

2.2 The rate of sickness absence in NICS is significantly higher than in UK counterparts. The latest complete set of data available is for 2017-18 and indicates that NICS sickness absence levels were almost double that of the Home Civil Service and significantly higher than the Welsh and Scottish government rates (see Figure 2). Whilst sickness absence levels in the private sector and non-profit sectors have shown a steady decline in the last five years, there has been little change in NICS absence levels in the same period.

2.3 One in eight NICS employees had a long-term sickness absence in 2019-20 and the average length of long-term absence was 63 days. Long-term absences accounted for over three quarters of all working days lost, the equivalent of the loss of 951 full time staff for an entire year. However, we also note that half of NICS staff had no recorded spells of absence.

Sickness absence in NI local councils is consistently the highest in the UK

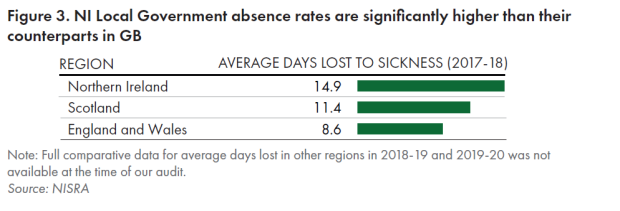

2.4 In 2016-17, sickness absence levels in NI councils peaked at their highest levels since 1990 at almost 15 days per employee. This figure remained consistent in 2017-18 at an average of 14.9 days lost per member of staff due to sickness. We note that the overall sickness absence level decreased to 13.9 days per employee in 2018-19 and that six of the eleven councils reduced their level of absence by more than ten per cent compared to the prior year (see Figure 5). However, sickness absence in NI councils continues to rank as the highest in the UK (see Figure 3).

2.5 Detailed information on sickness absence within the health and education sectors is not publicly available, therefore we have only been able to provide a high level summary of these sectors. In our view, the availability of detailed sickness absence data demonstrates a commitment to transparency and improvement (see paragraph 3.34).

2.6 The Department of Education reported that teaching staff in Northern Ireland lost an average of 9.5 days to sickness absence in 2018-19. This represents an increase of over 10 per cent in the last five years. Teachers’ absence levels are significantly higher in Northern Ireland than in Scotland and England, where the absence levels are six and four days per employee per year respectively.

2.7 Health and social care trusts report sickness absence in terms of the percentage of working days lost each year. The figures reported include both administrative and front line staff. Rates of sickness absence vary across the six trusts and ranged from 5.4 per cent in the Southern Trust to 11.5 per cent in the NI Ambulance Service Trust. The levels in each individual trust have remained relatively stable over the last five years.

The Northern Ireland public sector has undergone a period of significant organisational change

2.8 The Stormont House Agreement (December 2014) committed the Northern Ireland Executive to a comprehensive programme of reform and restructuring. This included measures to reduce pay bill costs and reduce the size of NICS and wider public sector. Around £700 million was made available to fund voluntary exit schemes across the public sector over the four years to 2018-19. At 1 July 2014 the headcount of NICS employees was 27,942. By 1 July 2019 this had reduced to 22,842, a decrease of over 18 per cent. Whilst these voluntary exit schemes have generated significant cost savings, some NICS managers have commented on the impact on remaining staff, particularly on the loss of key skills, increased workloads and a deterioration in morale.

2.9 The local government sector in Northern Ireland has also experienced significant reform. The Local Government Act (Northern Ireland) 2014, provided for a reduction in the number of local councils from 26 to 11 on 1 April 2015. Powers such as planning and local economic development have transferred from central government.

The proportion of NICS staff aged over 50 is more than double that of the working age population

2.10 NICS has an older age profile than the economically active working age population in Northern Ireland (see Figure 6). Over 40 per cent of civil servants were over the age of 50 in 2019, compared to 18 per cent of the economically active population. Less than one per cent of NICS staff were aged between 16 and 24. Whilst older employees do not have more instances of sickness absence (in fact they have the second lowest incidence of absence), when they are absent, it tends to be for longer periods of time.

2.11 The prevalence of some illnesses, including cardiovascular conditions, cancer and arthritis, are a function of age, and it follows that an older workforce will experience higher rates of these conditions. It is to be expected that these serious illnesses might require longer periods of absence. Amongst the over 55 age group, the average duration of a sickness spell was 20 days in 2019-20, compared to 12 days for the 25 to 34 age group.

2.12 Declining pensions, the rising state pension age and increasing costs of living, and an ageing population mean that people are working longer than ever. Older employees can offer organisations a number of benefits, including experience, ability to mentor newer staff, lower recruitment costs and higher retention levels. As older employees continue to make up a significant proportion of the public sector workforce, managing an ageing workforce is likely to become more important, therefore organisations should consider how they can best support the health and wellbeing of older employees.

Mental health issues are a significant and growing cause of sickness absence

2.13 One third of the UK workforce has been formally diagnosed with a mental health condition at some point in their lifetime, most commonly depression or general anxiety.

2.14 The statistics published by NISRA demonstrate that mental health problems are a prominent cause of long-term sickness absence in NICS. Over 102,000 working days were lost due to anxiety, stress and depression in 2019-20. Almost one third of the days lost in this category were attributed to work related stress. The average duration of an absence spell due to one of these mental health conditions was over 41 days, the third highest average duration recorded.

2.15 Almost all of the organisations that we spoke to recognised that conditions related to mental health have a significant impact on sickness absence, and told us that mental health awareness and support is an important focus of their wellbeing initiatives. During the course of our discussions with HR professionals we heard about a number of promising initiatives.

Case example: Working Age Services Directorate in the Department for Communities has delivered a range of mental health initiatives for staff over the past two years, focusing on the issues that affect staff in these largely customer facing roles. In particular, a bespoke course on resilience was co-designed between departmental staff and the Employee Assistance Programme provider. This course included modules on personal, emotional and team resilience. Feedback from participants highlighted their increased ability to recognise stress in their own and others’ behaviour and take steps to reduce anxiety and adapt their behaviour when dealing with other people.

Case example: Lisburn & Castlereagh City Council has recently trained 28 employees as Mental Health First Aiders, providing support for colleagues experiencing mental health problems at work. These employees have also been trained to recognise signs and symptoms of mental ill health and respond appropriately. Network meetings are held on a quarterly basis to allow the first aiders to support each other and generate ideas to support colleagues experiencing mental health issues.

Reducing long-term sickness absence is a particular challenge for the public sector

2.16 Short-term sickness absence is not as significant a challenge, as losses to the employer are manageable, both financially and organisationally. Sickness absence becomes a problem when these periods are protracted. Additionally, when individuals have been absent for a longer period of time, their likelihood of ever returning to work diminishes. A report from the Department for Work and Pensions found that people whose long-term absence spell lasted for one year or more, were eight times more likely to leave work following their sickness absence than those with a four week absence.

2.17 The majority of sickness absence in the NI public sector is caused by periods of long-term absence. Although long-term absences represented around 20 per cent of NICS absence spells in 2019-20, they accounted for over three quarters of the working days lost. This pattern is also reflected in the local councils, where almost two thirds of the days lost were due to long-term sickness absence in 2018-19.

2.18 When a small number of staff account for a large number of days lost, a reduction in the level of long-term sickness absence can have a significant impact on the level and cost of absence. In addition, the longer that someone is off sick or out of work, the harder it is to return to work, and this comes at significant financial and personal cost to the individual.

Part Three: Managing attendance: key principles and good practice

Public sector organisations must focus on the key principles underpinning attendance management

3.1 Managing attendance is a complex issue, particularly managing cases of long-term sickness absence. However, the prevalence and significance of sickness absence in the public sector indicates that a concerted effort is now required to reduce absenteeism and develop a consistent approach to this important issue. We have identified key principles in the management of attendance that are consistent across the public sector, based on supporting the health and wellbeing needs of employees while providing clear and consistent guidance for employers to avoid excessive absence levels. Following our engagement with HR professionals in the public sector, we have also highlighted examples of good practice and promising initiatives where they exist.

Principle one: Organisations should develop and promote a strong attendance culture

Sickness absence policies, procedures and systems should be consistent, transparent and easy to implement

3.2 Organisations should have robust sickness absence policies with simple, clear trigger points for management action, particularly when an employee is absent for a longer period of time. Trigger points ensure that an organisation uses the same criteria throughout for deciding when an employee’s absence is becoming problematic and requires action. Organisations have an obligation to ensure that sickness absence policies are consistently applied and that all absence is properly recorded, measured and reported. It is also important that sickness absence policies, particularly within the same sector, are consistent and comparable.

3.3 However, we noted that some organisations operate a number of different sickness absence policies within the same team. Some local councils have retained sickness absence policies from the legacy council structure, using as many as four separate policies in some cases. A single sickness absence policy is a more efficient and effective way to manage attendance within any organisation, enabling line managers to understand and implement the policies consistently, without any potential perception of unfairness.

Recommendation 1

Public sector organisations should regularly review the effectiveness of sickness absence policies and procedures to ensure that they are being implemented fairly and consistently and that they are fit for purpose. Organisations which have more than one sickness absence policy in operation should implement a single policy as soon as possible.

Employers and employees should be properly trained in the organisation’s sickness absence policy

3.4 Employers and employees need to understand the organisation’s sickness absence policy and the trigger points. It is essential that all employees are trained in the organisation’s sickness absence policy and understand the procedures to follow when they are unable to attend work due to illness. Employees should also be made aware of the consequences of failing to comply with the sickness absence policy and disciplinary actions that will be taken in the case of persistent absence.

3.5 For sickness absence policies to be successful, line managers need appropriate training and support to implement them. Where managers are not prepared and trained to manage sickness absence there is a risk that incidences will not be well managed and may escalate. This could result in unnecessary disputes, additional costs and reduced productivity. Training and communication should also continue beyond the introduction to the policy. Regular refresher training on the policy and visibility of absence targets in staff communications demonstrates an organisation’s sustained commitment to improving absence rates.

3.6 Development programmes for line managers can enhance an organisation’s ability to manage absence internally. Antrim and Newtownabbey Borough Council has invested in capacity building with a 3-tier management programme (iLead) to boost line managers’ skills and confidence to guide staff through change processes. Regular one-to-one meetings between line managers and employees aim to cascade a coaching culture through the organisation, as well as building in opportunities to ‘check-in’ and address work or personal issues at an early stage. The programme includes a course on attendance management which aims to help supervisors to confidently deal with sickness absence and support their staff to enable a return to work. It is encouraging to note that the Council emphasises attendance management as a key priority for line managers and provides opportunities to develop skills in this area.

Recommendation 2

Organisations should ensure that all those with line management responsibility receive regular training on sickness absence policies and procedures.

Individual roles should be well defined and understood by all employees

3.7 In each case of sickness absence a number of individuals and services may need to be involved, including the line manager, senior management, HR, Occupational Health Services (OHS) and Employee Assistance Programmes (EAPs). For a sickness absence policy to be effective, it is essential that these respective roles are well defined and clearly understood.

3.8 Line managers are best placed to monitor and respond to the absence of staff reporting to them, as they know them personally and see them on a regular basis. Line managers are also well placed to monitor patterns of sickness absence in their own teams. Additional support and guidance from HR and OHS should be available when required. NICSHR, the centralised HR function for NICS, told us that they are in the process of rolling out a change management programme in relation to managing attendance across the nine civil service departments.

Case example: NICSHR Employee Relations Change Management Project

NICS HR functions were centralised within the Department of Finance (DoF) in April 2017. Prior to this centralisation, each department had its own HR team which was responsible for managing the attendance system and associated processes. Under these arrangements, although adhering to NICS sickness absence policies, some departments had differing approaches and practices in relation to how they managed attendance.

When HR functions were transferred to DoF, absence meetings and disciplinary action become the responsibility of the newly formed NICSHR team, with departments retaining responsibility for day-to-day absence recording and monitoring. However, NICSHR is in the process of rolling out a change management programme which includes introducing a standard approach for absence management across NICS, with line managers having the authority for making key decisions about their staff’s attendance.

The changes to how attendance is managed will be introduced within departments incrementally, starting with stage one which involves line managers conducting sickness absence meetings. A range of support is available to line managers throughout this implementation period and includes a new suite of absence letters, step-by-step user guides and one-to-one support provided by NICSHR Employee Relations case managers. Stage one was fully implemented in seven of the nine departments by March 2020.

The introduction of a protocol for early and focused support for managers and staff is stage two of the change to the management of sickness absence in the NICS and is ongoing. NIAO will continue to seek updates on the project as it proceeds.

Commitment to sickness absence management should come from the top of the organisation

3.9 A strong culture and commitment to promoting attendance should come from the top of an organisation. Health and wellbeing should be a core priority for senior management who recognise the strategic importance of a healthy workplace. Organisations should demonstrate senior management and board level commitment to improving sickness absence. Whilst information recording and management reports are an important part of the attendance management system, is it vital that this information is presented to senior management.

3.10 Leadership should extend beyond endorsement of programmes and involve active and visible participation of senior management in wellbeing initiatives. Performance objectives for senior leaders in the public sector should include supporting the health and wellbeing of their employees. Performance reviews should consider a range of measurements, which may include sickness absence, staff survey results and the proportion of staff engaging with wellbeing initiatives.

3.11 Standalone wellbeing programmes are now common practice in the public sector, however some organisations are going beyond this and instituting a co-ordinated programme of wellbeing initiatives with regular monitoring at board level, embedding a commitment to employee wellbeing in the organisation’s culture.

Case example: Antrim and Newtownabbey Borough Council – Engage and Deliver Strategy

Antrim and Newtownabbey Borough Council’s Employee Engagement and Wellbeing Strategy, “Engage and Deliver”, recognises the correlation between employee engagement, wellbeing and organisational performance.

The strategy also identifies the need for employees to understand their connection to the Council’s corporate vision and is aligned to the Council’s Corporate Plan and its four key themes – Performance, People, Place and Prosperity.

The Council has placed engagement at the centre of its business, adding it as a corporate Key Performance Indicator. A comprehensive communication programme, including team meetings, email e-zines and recognition events, showcased staff achievements and promoted ways for staff to support their own wellbeing, and has led to 85 per cent of staff reporting that communication was good.

Other activities included within the strategy are as follows:

- training for line managers on absence management;

- streamlining staff sickness reporting procedures;

- communication of Occupational Health Service, Employee Assistance Programmes and counselling;

- delivery of health events linked to the top three reasons for absence each year;

- roll out of a Mental Health Toolkit;

- 100 per cent attendees get a letter of recognition for full attendance from the Mayor; and

- on-site access to cancer screening via the Action Cancer ‘Big Bus’ twice yearly.

The Council employs a range of measures to assess the impact of the strategy, including:

- an annual corporate objective to reduce absence;

- number of referrals to occupational health;

- increase in participants at health events;

- increase in mental health training for managers;

- reduction in long-term absence; and

- sustaining the number of employees with 100 per cent attendance.

Recommendation 3

Health and wellbeing initiatives must be backed by strong leadership and visible support from leadership of the organisation. We recommend that sickness absence statistics are regularly considered by senior management at board level. As part of this process, organisations should consider appointing a member of the senior leadership team to be an advocate for promoting good attendance.

Principle two: Prevention and early intervention is a cost effective way of reducing long-term absence

3.12 Long-term absence is the biggest driver of costs associated with sickness absence, and has the most significant impact on the delivery of front line services. Intervening and providing support at an early stage has the potential to allow employees to stay in work and therefore to reduce the financial impact of long-term sickness absence.

Organisations should encourage open conversations about health and wellbeing

3.13 It is important to normalise discussions about health and wellbeing, wherever possible and appropriate. This is not just about discussing health issues, but creating an environment where employees feel able to talk openly, particularly about mental health issues. Organisations should encourage conversations about physical and mental health and emphasise the support available when employees are struggling. Effective people management should include open conversations about health and wellbeing. It is vital that managers have regular conversations with their employees, giving them the opportunity to raise any issues and ensuring that potential problems can be addressed at an early stage.

With appropriate support, some employees will be able to remain in work

3.14 Robust and consistently applied sickness absence policies and procedures play an important part in managing attendance, however they do not always address the underlying causes of sickness absence. In many cases, preventing people from falling out of work because of ill health in the first place is better than having to pick up the pieces afterwards. The National Institute for Health and Care Excellence (NICE) guidelines, which aim to reduce the number of employees moving from short-term to long-term sickness absence and to help employees on long-term absence return to work, say that intervening at an early stage during sickness absence contributes to the success of the intervention.

3.15 Some causes of long-term sickness absence, such as stress, mental health issues and musculoskeletal conditions can emerge gradually and may have the potential to be managed alongside an individual continuing to work. Organisations should therefore focus their attention on these issues as the potential for reducing sickness absence, in particular long-term absence, is greatest.

3.16 There are various health and wellbeing interventions that organisations can provide to protect, support and improve the health of their employees. These may be used reactively, when a problem has occurred, or proactively, aimed at preventing health and wellbeing problems from escalating. Some common interventions include:

Employee Assistance Programmes

These provide confidential, independent support for employees to help them to manage personal and work problems which may affect their work performance, health and wellbeing. They generally include assessment, short-term counselling and referral services for employees and their immediate family.

Case example: USEL Workable Programme

Lisburn and Castlereagh City Council works in partnership with Ulster Supported Employment Limited (USEL), a public sector organisation that provides a wide range of employment programmes across Northern Ireland to assist and support people with disabilities or health related conditions into and within employment. USEL runs a programme in conjunction with the Council called Workable.

Workable is a flexible programme of support which assists people with disabilities or health related conditions, who face significant barriers to work, to find paid employment or to retain their current employment.

Support is specifically tailored towards the individual’s needs and may include:

- work preparation;

- job coaching;

- mentoring; and

- confidence building access to a range of accredited training opportunities.

The Council won the Employer of the Year award for the public sector at a ceremony championing the achievement of people with disabilities in the workplace in 2018.

Occupational Health Services

These provide an assessment of how an employee’s work might affect their health and can involve both:

- prevention - ensuring safe, comfortable working conditions; and

- intervention - helping employees to access services to help with return to work or making necessary adjustments to the working environment.

Employee Assistance Programmes should be evaluated and tailored to the individual organisation’s circumstances

3.17 Wellbeing strategies should include ways of raising awareness of support services that are available to staff. EAPs are common in public sector organisations. The goal of an EAP is to help employees to deal with personal, family and work issues and consequently participate fully and productively in the workplace. There is often a misconception that EAPs provide only counselling, when in fact they can offer a much wider range of support services. EAPs tend to be referred to when people are in crisis. However, these services have much more to offer, such as legal advice, help with debt management and support for caring issues. Providing access to early interventions could reduce the disruption to services caused by subsequent staff absence. Any promotion of EAPs should emphasise the preventative potential of these services.

3.18 It can be challenging to measure the impact of wellbeing initiatives and EAPs, however it is important that organisations know whether the approach they are taking is having the intended effect. Information provided by EAPs should be used to inform wellbeing strategies. Although confidentiality must be protected, general feedback can provide useful information on absenteeism and workplace issues. Employers should seek to maximise the gains possible from EAPs, analysing any reports provided, feedback from employees and monitoring the utilisation rates for services. Ongoing evaluation should be used to develop and design future wellbeing programmes. It may also enable organisations to target support at individual business areas experiencing particular wellbeing problems, such as greater than normal stress levels, or areas where uptake of support services is low. Finally, feedback that demonstrates the demand for and impact of these services can be a useful tool to build a case for future spending on wellbeing.

Recommendation 4

Organisations should monitor feedback and data to further improve Employee Assistance Programmes and ensure that they are as responsive as possible to employee needs.

Principle three: Organisations should focus on reducing and managing long-term sickness absence

3.19 A considerable proportion of public sector sickness absence is attributable to a relatively small number of long-term absences. When an individual has been absent for a longer period of time their likelihood of ever returning to work decreases, and the impact on the organisation and pressure on remaining staff increases. The management of long-term sickness absence usually requires consideration of whether the individual is capable of returning to work and when this might be, and the involvement of specialist health services such as OHS. There are a number of other factors that can contribute to the successful management of long-term sickness absence.

Quality of communication can have a significant impact on absence levels

3.20 There are two main stages in managing an employee’s long-term sickness absence:

- managing the period of absence itself; and

- managing and maintaining a successful return to work.

The individual line manager and the quality of their relationship with staff can have a significant influence on absenteeism levels and successful return to work. NICE guidelines on workplace health recommend that organisations make contact with employees who are off sick as early as possible, and within four weeks of the start of their sickness absence, depending on the circumstances. Further NICE guidance on keeping in contact with employees who are absent from work due to illness are outlined below.

NICE recommendations on keeping in touch with people on sickness absence

When contacting the employee:

- Be sensitive to their individual needs and circumstances.

- Be aware that communication style and content could affect their wellbeing and decision to return to work.

- Ensure that they are aware that the purpose of keeping in touch is to provide support and help them return to the workplace when they feel ready.

- If an early referral to support services (for example physiotherapy, counselling or occupational therapy) is available through the organisation’s occupational health provider, discuss if this may be helpful.

- Discuss how they would like to be contacted in future, how frequently and by whom. If the line manager is not the most appropriate person to keep in touch, offer alternatives.

- Provide reassurance that anything they share about their health will be kept confidential, unless there are serious concerns for their or others’ wellbeing.

Ensure that members of staff responsible for keeping in touch with people on sickness absence:

- are aware of the need for sensitivity and discretion at all times;

- understand the organisation’s policies or procedures on managing sickness absence and returning to work; and

- are competent in relevant communication skills and are signposted to and encouraged to use online or other resources and advice to improve these skills.

3.21 Keeping in regular contact with employees who are off with long-term sickness is primarily a line management responsibility. Line managers should ensure that employees know that the purpose of keeping in touch is to provide support and help with a return to the workplace when they feel ready. At the same time, line managers must ensure that they understand the organisation’s policies and procedures on managing sickness absence and that they are applying them consistently and fairly.

3.22 An employee on long-term sick leave might feel isolated and miss the social element of the workplace. Line managers should take proactive steps to keep in touch so that the employee knows that the organisation is interested in their health and wellbeing and that support is available during their absence. The frequency and method of contact is a matter of judgement and will depend on the individual circumstances and the nature of the illness. The employee also has a responsibility to keep their line manager updated on any medical or other information relevant to their illness or impacting their potential to return to work.

Case example – Department for Communities

The Department for Communities (DfC) has consistently had the highest levels of sickness absence within NICS. A number of DfC teams have implemented case conferencing procedures in an attempt to tackle high levels of absenteeism, and in particular long-term sickness absence.

Team managers meet with NICSHR once a month to review every long-term absence within the team. The purpose of case conferencing is to assist the individual’s manager to obtain information, advice and guidance on how best to support and manage an individual absence case.

By discussing the employment circumstances and medical background of the employee and the OHS recommendations, a case conference aims to reach a common understanding of the issues and to agree a way forward with specific actions.

This may be particularly helpful where managers have concerns regarding: long-term sickness absence; failure to resolve a problem satisfactorily; queries or difficulty regarding fitness to return to work; the nature of adjustments or restrictions required to allow a return to work; or concerns regarding the ability of management to accommodate such adjustments.

DfC told us that case conferencing had helped to focus attention on ensuring that actions required to help employees back to work, such as regular supportive contact, referrals to OHS at the correct trigger point, review meetings and reasonable adjustments offered, were taken at the appropriate time.

Further reviews are undertaken at a strategic level between directors and senior HR colleagues. This gives senior leadership teams the chance to look at trends and issues and identify where more support or early intervention is required. It also means that senior managers are more aware and accountable for absences within their teams, and reinforces the intention that attendance management is a collective responsibility.

In January 2018, a DfC processing centre with almost 500 staff was amongst the top 10 departmental “hot spots” for high levels of sickness absence. Through a number of initiatives including case conferencing, mental health awareness and support, by April 2019 it had fallen out of the top 10. In another division, the number of long-term absence cases has fallen by over 10 per cent in the year since case conferencing was implemented.

Recommendation 5

Internal communication is an important factor in the successful management of long-term sickness absence. Organisations should develop protocols for specialist services such as OHS, HR professionals and line managers to work closely together.

Timely access to specialist health services and professional advice is important

3.23 Ensuring quick, easy referral to specialist health services is an important aspect in helping employees get back to work from sickness absence. Those with more serious conditions, often referred to as “red flag” conditions, should be identified and referred to specialist services at the earliest opportunity. A study by the Work Foundation reviewed 13,000 musculoskeletal disorder cases in Madrid and found that referring employees to specialist treatment after five days reduced the number of days off work by 39 per cent and the number of employees never returning to work by 50 per cent.

3.24 OHS provides an opportunity to assess an employee’s needs and potentially facilitate a quicker return to work, through additional support and reasonable adjustments. The NICS sickness absence policy states that “an OHS referral will always be considered once it becomes evident that the absence may exceed 20 working days. However earlier or more urgent referrals to OHS may be made where Departmental HR, line management or you consider such an intervention to be helpful.”

3.25 During our discussions we heard that within NICS, referral to OHS is very rarely considered before the 20 day threshold is met. Other organisations, including a number of councils, refer employees to occupational health services immediately in certain circumstances, for example where the absence is work related, due to stress or relates to substance misuse. In some cases, a delay accessing specialist interventions can increase the barriers employees face in returning to work, as physical health problems may become chronic, and common mental health problems such as depression and anxiety may emerge as a result of being removed from work and uncertainty about the future.

Recommendation 6

Organisations should ensure that employees experiencing serious conditions are referred to appropriate specialist health services in a timely manner.

Supporting a sustainable return to work may help to prevent the recurrence of absence

3.26 For employees, returning to work can represent a return to a sense of normality and can lead to an increase in self-esteem as well as financial stability and independence. Organisations should recognise the need to be flexible when someone is ready to return to work after a long-term sickness absence. Returning to work after a long or serious illness can be a culture shock and therefore the return needs to be properly supported, for example through a phased return to work. Organisations may also need to consider any adjustments that might need to be made to the employee’s working environment or tasks.

3.27 People who have experienced mental health conditions may require ongoing support and workplace adjustments in order to sustain a successful return to work. A well planned return to work process will have substantial benefits for the employee’s wellbeing and could also prevent potential relapses. NICE guidelines recommend that when people have been absent for four or more weeks for a common mental health condition, employers should consider a three month structured support intervention upon their return. Line managers play a vital role in facilitating the return to work process and so it is important that they are trained and supported to manage this effectively.

Fair and consistent action should be taken in cases of unacceptable absence

3.28 Adopting disciplinary measures is a direct means of tackling unacceptable absence. Organisations we spoke to highlighted the importance of having a formal process to deal fairly and consistently with absences that can no longer be sustained.

3.29 Organisations should consider moving towards dismissal procedures if a medical report is not able to give a realistic timeframe for a return to work, and they have considered any reasonable adjustments to help the employee back to work. Organisations should ensure that they have followed their sickness absence policy in full, including being able to demonstrate that they have considered all available options and taken reasonable steps to support an employee back to work. The following list highlights typical considerations for an employer before progressing to dismissal.

Typical considerations for employers prior to dismissal

- Have you maintained regular communication, including structured review meetings, with the employee?

- Is the employee aware of the full process and the potential outcomes?

- Have you obtained appropriate advice from occupational health or other medical professionals?

- Have you considered whether any adjustments can be made to support a return to work?

- Have you explored the option of redeployment?

- Have you explored whether ill health retirement is appropriate?

- Can you explain the impact that the absence is having on the organisation and why the position is no longer sustainable?

Recommendation 7

All organisations should have a formal inefficiency procedure to deal with unacceptable levels of absence, and senior leadership teams should ensure that these are implemented when required.

Principle four: Organisations should measure, analyse and understand the impact of sickness absence

3.30 Joined up sickness absence management procedures should be supported and informed by relevant, reliable and timely data. Reliable data provides a firm foundation for successful sickness absence management and ensures that the absence position is visible to both employees and management. Sickness absence management systems should give line managers the tools they need to monitor, analyse and report on sickness absence. Information is needed at a team level to ensure that line managers are adequately informed about the staff they are responsible for. Regular and timely corporate reporting also allows senior management to make comparisons across the organisation and identify areas of good practice to be shared.

3.31 During the course of our discussions with HR professionals, we encountered a range of methods for recording and reporting sickness absence data. In our view, regular, consistent reporting to senior management demonstrates organisational commitment to tackling high sickness absence levels. Some examples of the information gathered and presented to senior management included:

- performance against overall organisational target and individual service area targets;

- cost of agency cover due to absence;

- main causes of absence;

- split of long-term and short-term cases; and

- details of long-term cases and actions taken to date.

3.32 Whilst we noted some good examples of reporting to senior management, we also noted inconsistencies in the type and nature of information presented. For example, some organisations attempt to calculate the costs of replacing absent staff with temporary workers, whilst others do not make any effort to estimate these costs. In our view, it is important that organisations understand the impact of high levels of sickness absence, in terms of service delivery, staff morale and financial costs.

Recommendation 8

In order to monitor and improve sickness absence levels it is essential to have accurate, timely and accessible information. Organisations should collect sufficient data to enable sickness absence reasons and changing trends to be monitored. Monitoring should include an attempt to calculate, analyse and report the costs of sickness absence if this is not already done.

Good practice should be shared across the public sector

3.33 There is scope for sharing best practice across the public sector. The Public Sector People Managers Association (PPMA) Absence Group provides an opportunity for HR professionals to share information and examples of good practice. While not all initiatives will be transferable to different working environments, there is scope for more extensive sharing of good practice across the public sector.

3.34 NISRA publishes annual sickness absence statistics for NICS, and sickness absence statistics are publicly available for the local councils, however it is unclear if public sector organisations use such data for benchmarking. NISRA can also provide ad hoc reports on specific aspects of sickness absence for individual NICS departments. In Part Two we noted that information on sickness absence within the health and education sectors is not available in the same level of detail as for NICS, which meant that we were unable to compile comparative data on these sectors (see paragraph 2.5).

Recommendation 9

Consideration should be given to establishing arrangements to allow for the sharing of good practice from across the public sector. Central government organisations should also review the information available to them from NISRA and consider benchmarking their performance, where appropriate. Organisations that do not currently make detailed sickness absence information publicly available should be encouraged to do so.

Appendix 1:

Sources of Research

In compiling this guide, we have drawn upon a range of available good practice guidance including:

- Workplace health: long-term sickness absence and capability to work, National Institute for Health and Care Excellence, November 2019

- Working Well A Plan to Reduce Long Term Sickness Absence, Institute for Public Policy Research, February 2017

- Working for a healthier tomorrow, Dame Carol Black, March 2008

- Sickness absence and health in the workplace: Understanding employer behaviour and practice, Department for Work and Pensions, June 2019

- NHS Health and Well-being Review, Dr Stephen Boorman, 2009

- Guidelines on prevention and management of sickness absence, NHS Employers, November 2013

- Health at work – an independent review of sickness absence, Dame Carol Black and David Frost CBE, November 2011

- Health and Wellbeing at Work, Chartered Institute for Professional Development, April 2019 Thriving at work – the Stevenson/Farmer review of mental health and employers, Paul Farmer and Dennis Stevenson, October 2017

- Attendance Management: a review of good practice, S Bevan and S Hayday, 1998