This report has been prepared under Article 8 of the Audit (Northern Ireland) Order 1987 for presentation to the Northern Ireland Assembly in accordance with Article 11 of the Order.

K J Donnelly CB

Northern Ireland Audit Office

Comptroller and Auditor General

1 March 2022

The Comptroller and Auditor General is the head of the Northern Ireland Audit Office. He, and the Northern Ireland Audit Office are totally independent of Government. He certifies the accounts of all Government Departments and a wide range of other public sector bodies; and he has statutory authority to report to the Assembly on the economy, efficiency and effectiveness with which departments and other bodies have used their resources.

Abbreviations

AGPs Aerosol Generating Procedures

BAU Business as Usual

BSO PaLS Business Services Organisation Procurement and Logistics Service

COIs Conflicts of Interest

DACs Direct Award Contracts

DHSC Department of Health and Social Care

DoH Department of Health

DPS Dynamic Purchasing System

EU European Union

HCID High Consequence Infectious Disease

HSC Health and Social Care

HSENI Health and Safety Executive Northern Ireland

IA Internal Audit

ICS Independent Care Sector

IHCP Independent health & care providers

IPC Infection Prevention and Control

ISPs Independent Service Providers

JIT Just in Time

MOIC Medicines Optimisation Innovation Centre

NIAS Northern Ireland Ambulance Service

PHA Public Health Agency

PIPP Pandemic Influenza Preparedness Programme

PPE Personal Protective Equipment

RCN Royal College of Nursing

RQIA Regulation and Quality Improvement Authority

RWCS Reasonable Worst Case Scenario

Key figures

£397 million The cost of core PPE items ordered by BSO PaLS between January 2020 and April 2021.

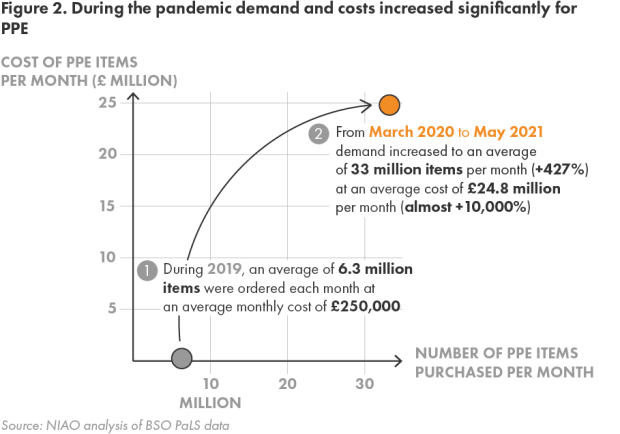

£0.25 million BSO PaLS monthly spend on PPE prior to the pandemic.

£ 24.8 million BSO PaLS monthly spend on PPE during the pandemic.

1.34 billion The number of PPE items procured for local healthcare providers during the pandemic. In contrast, annual pre-COVID demand amounted to only 75 million items.

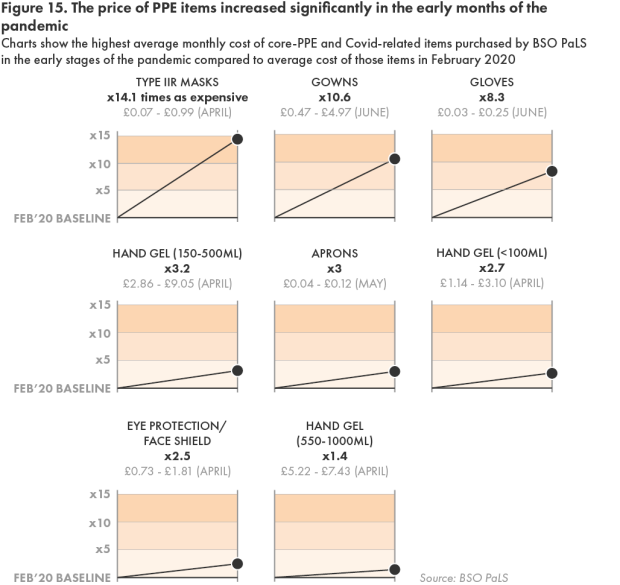

957% and 1,314% The average cost increases for gowns and Type IIR masks in the early months of the pandemic.

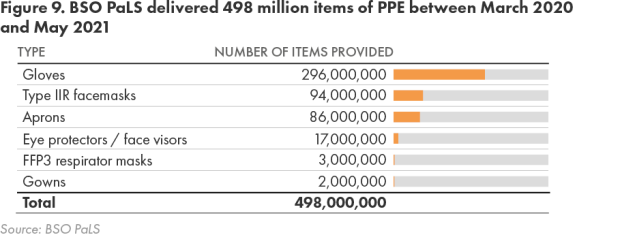

498 million The number of core PPE items delivered by BSO PaLS to local healthcare providers between March 2020 and May 2021.

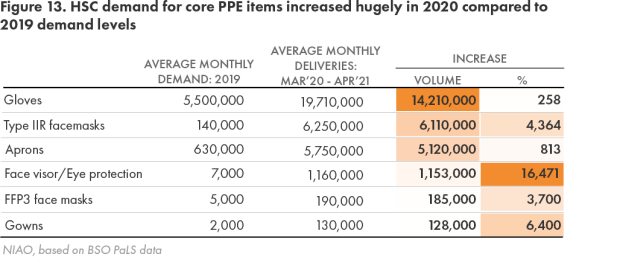

429% The overall increase in demand for core PPE items from healthcare providers. Demand for more sophisticated items rarely previously used increased between 3,700% and 16,500%.

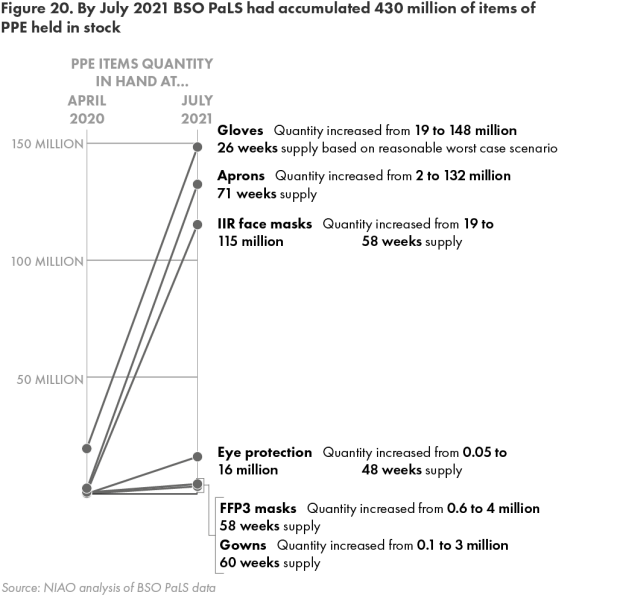

One week or less Supply levels of various PPE items held centrally by BSO PaLS in the early stages of the pandemic in March 2020. In contrast at July 2021, it held between 26 weeks and 71 weeks supply for the various items.

420 million Total items of core PPE held in stock by BSO PaLS in July 2021.

Executive Summary

1. Personal Protective Equipment (PPE) is vital in helping control the spread of infections in health and social care settings. Its use has significantly assisted attempts to manage and minimise COVID-19 transmission rates globally since early 2020. However, PPE must be readily available, of sufficient quality, and supported by clear guidance governing its use.

Demand and supply arrangements prior to the pandemic

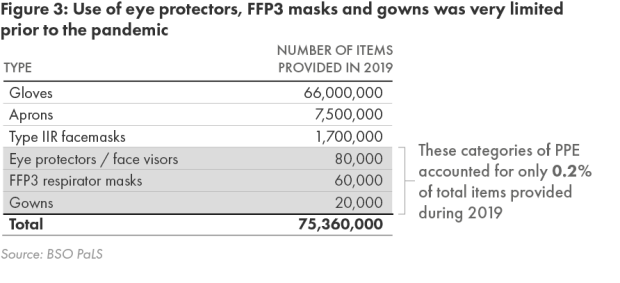

2. Prior to the pandemic, relatively few local Health and Social Care (HSC) sector staff required PPE. Gloves, aprons and Type IIR masks collectively accounted for over 99 per cent of demand, with very limited use of more sophisticated equipment such as eye protection, face visors, FFP3 (respirator) masks and gowns. Independent care sector (ICS) usage was also mainly restricted to gloves and aprons for standard infection control purposes.

3. PPE used by the HSC sector was almost exclusively procured by the Business Services Organisation Procurement and Logistics Service (BSO PaLS), an independent body of the Department of Health (DoH or the Department) , and annual expenditure was just under £3 million. BSO PaLS did not however, have responsibility for emergency planning for stockpiles of PPE for events such as a pandemic. Within the ICS, each individual provider procured their own PPE.

Supplying PPE to local healthcare providers

4. This stable situation changed dramatically with the arrival of COVID-19. Overall demand for PPE increased sharply, rising by 429 per cent in comparison to 2019. The need for specific items also spiked – by between 3,700 per cent and 16,500 per cent for items only previously used on a limited basis. At the same time, intense global demand meant supplies became very limited.

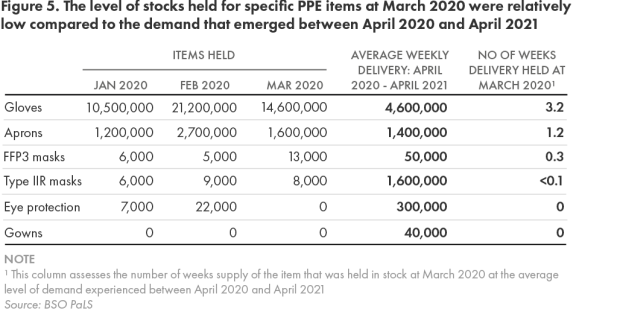

5. In the midst of considerable uncertainty over future demand, BSO PaLS decided on 27 January 2020 to increase its PPE stockholding from 4 weeks to 12 weeks supplies. However, the high subsequent demand meant that this would have equated to less than one week’s supply for dealing with COVID-19. By March 2020, BSO PaLS held just over 16 million core PPE items. It had no stocks of fluid repellant gowns or visors as demand for these among local healthcare providers was very limited prior to the onset of COVID-19. Compared to usage experienced during the pandemic, the supplies held equated to around one week’s supply of aprons, and less for all other items apart from gloves.

6. With concerns emerging that increased ordering by HSC staff had led to stock levels running very low, the Chief Pharmaceutical Officer, following advice from BSO PaLS, directed it to introduce demand management arrangements on 23 March 2020. From that date, BSO PaLS began allocating supplies of available PPE directly to HSC Trusts, who attempted to deploy this in a more prioritised way.

7. By March 2020, DoH was acknowledging significant issues over local PPE availability. In that month, the Royal College of Nursing (RCN) and Independent health & care providers (IHCP) both reported many members raising significant concerns over availability, particularly for FFP3 (respirator) masks. They stated that they had repeatedly highlighted these issues to DoH and other HSC organisations. BSO PaLS told us that whilst it occasionally ran out of specific requested FFP3 masks, it always had access to alternative models. Both bodies continued raising concerns into April 2020, particularly in respect of independent sector care homes.

8. Department of Health (DoH) guidance issued in March 2020 outlined that independent providers were required to source their own PPE, but that Trusts should try and ensure they had access to appropriate equipment. However, it also indicated that supplies should only be provided when suspected or confirmed COVID-19 cases arose. At this time, public heath guidance still stated that independent providers did not require enhanced equipment. IHCP maintains that, throughout March 2020, care homes only received small PPE supplies when Covid-19 was present, which did not properly address the considerable shortages in that sector.

9. A DoH review completed on 28 April 2020 acknowledged that “overall confidence in PPE supply is low”, and that “there are shortages of PPE stock in the system”, but also highlighted that “many have reported that over recent weeks the system has been improving”. Whilst stakeholders highlighted positive areas, including coordinated ordering and supply arrangements, they considered that challenges remained around availability, timeliness of supply and quality of PPE.

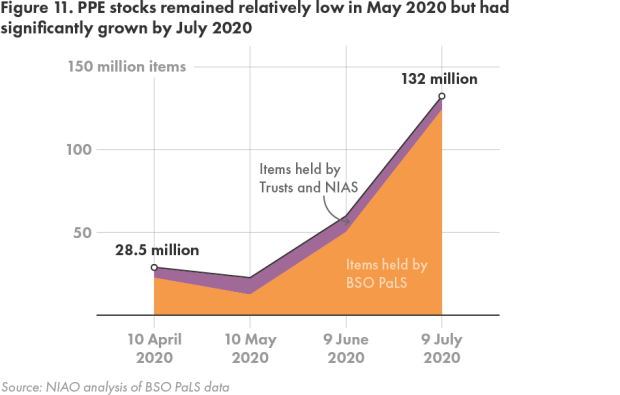

10. By late April 2020, the supply situation had considerably improved. Whilst in March 2020 BSO PaLS delivered just 17.2 million core PPE items, between April 2020 and May 2021, it provided an average of almost 32 million items every four weeks. By July 2020, its central stocks had increased to 132 million core items compared to 16 million items in March 2020. Overall, BSO PaLS has delivered 498 million core PPE items between March 2020 and May 2021.

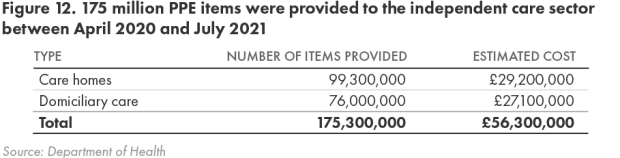

11. Supply to the independent sector had also increased, with providers routinely receiving PPE free of charge through Trust distribution systems. IHCP stated that independent providers were receiving adequate supplies by mid-April 2020, but that the situation only improved as COVID-19 cases in care homes began escalating. Independent sector providers have received over 175 million core and COVID-impacted items between mid-April 2020 and July 2021.

Costs and procurement methods

12. In the early stages of the pandemic, it became clear that existing contracts would be insufficient to provide reliable supplies or meet the hugely increased demand. In trying to identify new sources, BSO PaLS assessed over 2,000 potential leads, engaging 45 new suppliers between January 2020 and April 2021, from whom it has ordered almost 618 million core PPE items.

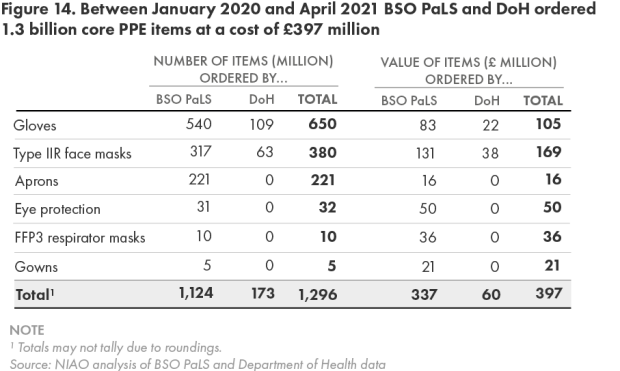

13. As well as these procurements, DoH signed a £60 million PPE contract in April 2020. Between January 2020 and April 2021, BSO PaLS and DoH raised purchase orders for 1.3 billion core PPE items, with a total cost of £397 million. Of this, £25.7 million related to competitive contracts, with almost all of the remaining £371.3 million relating to Direct Award Contracts (DACs) (i.e. untendered contracts)

14. The global supply shortages meant that the average costs of PPE purchased between April 2020 and June 2020 were significantly higher than early 2020 prices. This was particularly the case for gloves (733 per cent), gowns (957 per cent) and Type IIR masks (1,314 per cent). Some independent sector suppliers were also reportedly charging up to eight times the previous prices for various items. BSO PaLS referred 60 examples of cost inflation to the Competition and Markets Authority in May 2020, but proceeded with these orders to obtain PPE, spending almost £127 million. Although prices subsequently reduced, they have still remained above pre-pandemic levels.

15. Some contractors also began requesting payment in advance of supply. In one case, a supplier who received a £0.88 million prepayment failed to deliver an order for 2.5 million Type IIR masks. BSO PaLS had identified this supplier as high risk prior to contract signature, and has commenced legal action to try and recover this amount. The need for equipment meant that BSO PaLS placed orders with six `high risk’ suppliers. Aside from the unrecovered prepayment, no significant problems arose with these suppliers, although a September 2020 Internal Audit (IA) review highlighted BSO PaLS had engaged them without requiring any additional internal approval, and identified risks around multiple prepayments to the same suppliers and inadequate risk assessments on suppliers requesting prepayments.

16. Effective arrangements are required for identifying and managing conflicts of interest (COIs) for untendered contracts. BSO PaLS relied on existing controls involving annual staff declarations, and did not introduce any additional safeguards. It stated that no potential offers were `fast-tracked’, and all had to pass quality and specification assessments. No BSO PaLS staff have declared any COIs, but no further steps have been taken to identify any potential undisclosed conflicts.

17. Where supplier prices “varied considerably” from prevailing market rates, BSO PaLS highlighted that approval for a DAC was only sought where supply was in jeopardy, but acknowledges that this process was not documented. Such documentation would have helped provide a more complete audit trail of decisions taken, but BSO PaLS stated that its documentation complied with the Public Contracts Regulations 2015.

18. We recognise the commitment and work undertaken in very challenging circumstances by staff in DoH, BSO PaLS, HSC Trusts and other bodies to procure, store and distribute PPE throughout the pandemic.

The quality of PPE supplied and guidance, training and instruction in its use

19. The RCN expressed concerns to the Health and Safety Executive Northern Ireland in March 2020 that local fit-testing of FFP3 masks was then not widely available, potentially increasing infection risks. BSO did not let a single fit-testing contract at the outset of COVID-19 arriving in Northern Ireland as HSC Trusts had specific needs and given time pressures, it was more expedient for Trusts to award their own DACs for this service. As BSO PaLS had not let fit-testing contracts when COVID-19 arrived in NI, Trusts had to individually award DACs for this service. A Serious Adverse Incident investigation on the early quality of fit-testing remains ongoing. A review in mid-2020 identified that almost 2,900 HSC and ICS staff required further fit-testing. A regional fit-testing framework is currently being developed.

20. An April 2020 RCN membership survey identified that a significant proportion of local respondents were using donated, home-made or self-bought PPE. A DoH review in that month acknowledged that in some instances, the quality of PPE had been unreliable, with users reporting the “poor and unacceptable quality of some PPE supplies”. Despite this, DoH highlighted that equipment has only had to be withdrawn due to safety concerns in a relatively small number of instances, given the volume of PPE purchased, and was limited to certain types of facemasks, eye protection and gowns in the earlier stages of the pandemic.

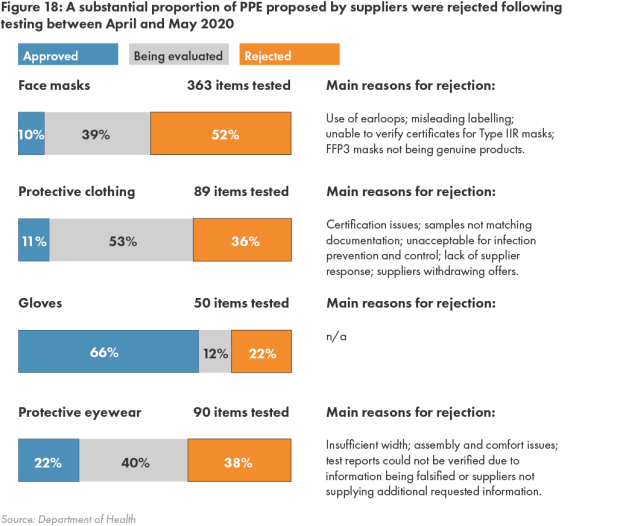

21. To gain assurance that newly offered PPE meets the required specification and quality, BSO PaLS established a detailed pre-procurement assessment from 1 April 2020. By mid-May 2020, almost 600 proposed items from 248 suppliers had been assessed, with 45 per cent being rejected. These validation processes are clearly valuable in identifying unsuitable equipment, but further work is ongoing, as HSC staff highlighted that some approved products had exhibited practical deficiencies when used in clinical practice.

The current situation and longer term planning

22. Reliable demand modelling for PPE was important given the high transmissibility and increased demands associated with COVID-19. However, a lack of information and frequently changing infection control guidance made it difficult to produce accurate projections for PPE needs.

23. BSO PaLS and the Public Health Agency (PHA) had collectively developed initial demand modelling in late March 2020. By late June 2020, the PHA and HCS Trusts had jointly developed further Reasonable Worst Case Scenario (RWCS) projections. With further refinements, BSO PaLS has used this approach with the target of building a 12 week RWCS stockholding. However, as actual usage has fallen below RWCS projections, BSO PaLS had accumulated large stocks of core PPE items that equate to between 48 weeks and 71 weeks supply by July 2021. A significant proportion of this PPE was procured under the higher cost DACs which were awarded during the `emergency’ phase of the pandemic, based on early modelling projections. BSO PaLS considers that these levels of stock are not dissimilar to those held elsewhere in the UK.

24. Given the initial supply chain problems, BSO PaLS, Invest NI, Construction and Procurement Delivery and DoH took various steps to encourage local businesses to begin manufacturing PPE, or increase existing operations. This resulted in seven DACs with a total estimated value of £165.8 million being approved with local businesses. To support more flexible and longer-term competitive procurements, BSO PaLS established a Dynamic Purchasing System (DPS) on 25 June 2020. To date, it has awarded two competitive contracts under this, totalling £38.3 million. The limited number of competitions to date reflects the very large stocks built up under the emergency regulation contracts. BSO PaLS is reviewing stock levels and demand, to inform further DPS procurements.

25. Prior to the pandemic, the cost of standard infection control PPE was included within DoH tariff rates to remunerate ICS providers for care provision. Whilst the free of charge provision has met the sector’s dramatically increased and changing PPE needs without imposing any increased cost burden, this policy is unlikely to continue indefinitely, meaning that the existing tariff may have to be reviewed. Some form of centralised procurement process across the ICS could also enhance security of supply, and deliver better value for money.

Learning Points

26. Whilst BSO PaLS existing PPE stocks sufficiently addressed pre-COVID demand, these were clearly inadequate for meeting the huge increase in demand which arose with the arrival of COVID-19. National contingency planning for an influenza pandemic also provided access to a useful but limited emergency PPE stockpile. Whilst BSO PaLS has now ensured security of PPE supply for the foreseeable future, it is important to consider how longer-term planning can be further enhanced to ensure no future repetition of the shortages experienced in the early stages of the pandemic.

27. The widespread use of emergency procurement regulations and ability to award contracts without competition proved critical in helping ensure that the hugely increased volumes and new types of PPE required for COVID-19 were secured, albeit at a considerable economic cost. To avoid having to excessively use such contracts in the future, local procuring authorities need to consider how supply chain resilience can be strengthened and made more flexible to address any significant future increase in demand, not only for PPE, but for other goods and services for which demand could increase significantly and suddenly.

28. Early concerns around the quality and suitability of some PPE issued to healthcare staff have largely been resolved through the introduction of innovative and collaborative quality assurance processes. To maintain staff confidence, it is important that these processes are sustained, and where possible, further enhanced.

29. In addition to considering how contingency and emergency planning arrangements can be strengthened, more work is required in the area of demand modelling. Longer-term supply arrangements for the ICS also need to be clarified. Ongoing assessments of PPE supply chain readiness to meet the needs of local healthcare providers are also required, given the potential for future waves of COVID-19 and for other infectious pandemics.

Part One: Introduction and Background

Introduction and Background

1.1 Personal Protective Equipment (PPE) is vital in helping control the spread of infections in health and social care settings. Its use has been important in managing and minimising the transmission of COVID-19 globally since early 2020. However, to be fully effective, PPE must be readily available, of sufficient quality, and supported by clear guidance governing its use.

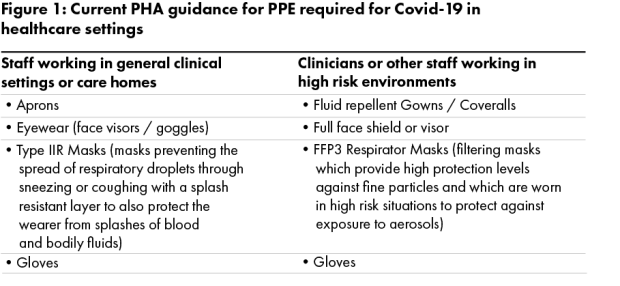

1.2 The PPE required to protect healthcare workers can vary according to their roles and duties, with staff working in high-risk environments, including those performing Aerosol Generating Procedures (AGPs) on patients, requiring higher protection. Figure 1 summarises the current Public Health Agency (PHA) guidance on the PPE recommended for COVID-19.

1.3 Before the pandemic, relatively few local health and social care (HSC) and independent care sector (ICS) staff needed to wear PPE, and acquiring it was reasonably straightforward. The PPE used by the HSC sector was predominantly procured by the Business Services Organisation’s Procurement and Logistics Service (BSO PaLS), an arms length body (ALB) of the Department of Health (DoH), and distributed to HSC providers from BSO’s warehouses. Within the ICS, individual Independent Service Providers (ISPs) procured their own PPE.

1.4 This stable demand changed dramatically in early 2020. The impending COVID-19 pandemic, and the need to try and minimise transmission of the virus, resulted in demand for PPE among local healthcare providers increasing sharply. As ISPs encountered considerable difficulties in securing the necessary additional PPE, DoH decided in mid-April 2020 that they would be proactively provided with supplies free of charge through the public sector supply chain until further notice.

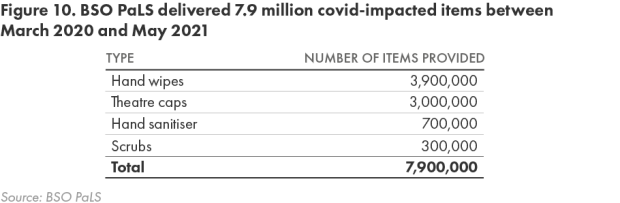

1.5 Compared to the 75 million `core’ PPE items the HSC sector required in 2019 (6.3 million items per month), BSO PaLS has provided 498 million items for use by local HSC and ICS healthcare providers between March 2020 and May 2021 (33.2 million items per month). This 427 per cent increase underlines the hugely increased volume of PPE required for COVID-19. BSO PaLS has also delivered 7.9 million `COVID-impacted’ items during this period. Before the pandemic, BSO PaLS spent just under £3 million annually on PPE. However, between January 2020 and April 2021, it ordered almost £400 million worth of core PPE to assist the response to COVID-19. This high spend reflects both increased demand and particularly in the early stages of the pandemic, high market cost inflation (Figure 2).

1.6 Several factors in the early stages of the pandemic exacerbated the challenges in meeting the increased demand. In early 2020, China (the largest global PPE manufacturer) introduced legislation which meant that only businesses with a medical device exporter licence could export PPE, which curtailed exports. Several other countries also imposed temporary export restrictions to help meet increased domestic demand. The hugely intensified global competition for equipment also resulted in supply shortages, as well as significant price increases.

1.7 The need to secure large volumes of PPE within tight timeframes means BSO PaLS has extensively deployed procurement measures which it would not otherwise have used. These have included:

- buying PPE through contracts let without competition (known as Direct Award Contracts (DACs));

- making prepayments to suppliers before equipment has been delivered; and

- engaging suppliers who were new to the PPE market, and as such, untested in this area. The urgency of need also means that it has had to procure from companies assessed as representing `high risk’.

Scope of review

1.8 This review focused on gathering the facts around the supply and procurement of PPE to the local healthcare sector before and during the pandemic. It examined:

- pre-pandemic demand for PPE, and procurement arrangements;

- pre-COVID contingency planning for any sudden increased demand for PPE, and how this was implemented;

- challenges encountered in identifying and meeting increased demand for PPE due to COVID-19, and the extent to which this has been met throughout the pandemic;

- total costs incurred on PPE procured for the healthcare sector during the pandemic, and levels of market cost inflation;

- the various means used to source and procure PPE;

- whether PPE procured has been of the required quality, and if staff have been given appropriate training and instruction in its use; and

- the current position regarding PPE supply and procurement, and scope for learning from the experiences of the pandemic.

As a 'facts only' report, we have sought, with the benefit of hindsight, to identify learning points (paragraphs 26 to 29), but have not drawn any firm conclusions on value for money.

Methodology

1.9 In undertaking this review, we:

- reviewed relevant DoH and BSO PaLS documentation and data, and held discussions with key staff from these organisations;

- engaged with the Royal College of Nursing (RCN) and Independent health & care providers (IHCP) to obtain their views and supporting evidence on the adequacy and timeliness of PPE supply during the pandemic, and on the quality of equipment, and guidance, training and instruction provided on its use; and

- liaised with colleagues from the National Audit Office, Audit Wales and Audit Scotland to discuss emerging issues and areas of common interest from our ongoing respective reviews in this area.

Part Two: Demand and supply arrangements prior to the pandemic

The HSC and independent care sector deliver key health and social care services and employ large workforces

2.1 The five Health and Social Care (HSC) Trusts each deliver regional integrated health and social care services across settings which include hospitals, health centres, residential homes and care centres. In addition, the Northern Ireland Ambulance Service (NIAS) provides a 24-hour regional ambulance service. These HSC organisations employ a large clinical workforce. In March 2020, in the early stages of the pandemic, there were approximately 22,500 staff within the nursing and midwifery workforce group, and just under 4,500 medical and dental group staff. The NIAS also employed 1,200 staff.

2.2 The local independent health and social care sector (or the independent care sector (ICS)) also provides key community-based social care services. At December 2020, the sector’s representative body `Independent health & care providers’ (IHCP), had 245 members, or Independent Sector Providers (ISPs), including private, voluntary, charitable and church affiliated organisations. At that date, these ISPs managed 437 of the 484 local care homes registered with the Regulation and Quality Improvement Authority (RQIA), provided around 15,000 of the 16,154 local registered care beds, and delivered homecare packages to around 24,000 people. Estimates indicate that the ICS collectively employs over 30,000 staff.

Prior to COVID-19, demand for PPE among local healthcare providers was limited and stable

2.3 Prior to the pandemic, relatively few HSC staff needed to wear PPE. In 2019, the HSC sector required 75 million core PPE items, with gloves (87.6 per cent), aprons (9.9 per cent) and Type IIR masks (2.2 per cent) collectively accounting for 99.7 per cent of these. Use of eye protection, face visors, FFP3 (respirator) masks and gowns was very limited (Figure 3) .

2.4 Whilst pre-pandemic figures for PPE usage within the ICS are unavailable, its needs were also mainly restricted to using gloves and aprons for personal hygiene and standard infection control purposes across care homes and homecare settings, with no requirement for facemasks, gowns or eye protection.

Annual pre-pandemic spend by the HSC sector on PPE was below £3 million

2.5 The PPE used by the HSC sector before the pandemic was almost exclusively procured by BSO PaLS. It purchased the vast majority of this through four fixed price contracts awarded through open competition. In 2019, BSO PaLS `spent just under £3 million on PPE. This included £٢.٧ million spent through its own contracts, £٢.٦ million (٩٥ per cent) of which related to gloves and aprons. BSO PaLS also spent £٠.٢ million on FFP3 masks through the NHS supply chain frameworks (the NHSSC Frameworks).

2.6 This PPE was stored in BSO PaLS warehouses to support the HSC sector’s `business as usual’ (BAU) working requirements. HSC staff at ward level had autonomy to electronically order the required PPE, which BSO PaLS then despatched directly to wards. The predictable demand patterns enabled BSO PaLS to manage stock levels in a way which maximised space utilisation and minimised stockholding. Alongside the seven to ten day supply of items held at ward level, BSO PaLS maintained approximately four weeks BAU supply of most PPE items.

2.7 In addition to BAU supplies, UK-wide contingency arrangements for a major influenza outbreak were established in 2011. These have included maintaining a central emergency `Pandemic Influenza Preparedness Programme’ (PIPP) stockpile of products, which includes some PPE items. Paragraphs 3.22 to 3.28 outline how these arrangements operated locally during the Covid-19 pandemic.

2.8 Within the ICS, each ISP procured their own PPE, and their existing suppliers were again generally able to meet their steady requirements. The cost of standard infection control PPE was included within tariff rates set by DoH to remunerate ISPs for care provision, but IHCP told us this was not specifically quantified.

2.9 These limited and stable PPE requirements changed dramatically with the onset of COVID-19 due to the highly transmissible nature of the virus. The remainder of this report considers:

- arrangements for supplying PPE across the local healthcare system and how well healthcare providers needs have been met throughout the pandemic (Part Three);

- costs incurred on PPE and procurement methods deployed (Part Four);

- the quality of PPE procured and training and guidance provided to healthcare staff on infection control and PPE usage (Part Five); and

- the current supply situation and scope for learning lessons from the pandemic (Part Six).

Part Three: Supplying PPE to healthcare providers

The highly transmissible nature of COVID-19 meant that healthcare provider demand for PPE increased massively

3.1 The limited and stable PPE requirements among local healthcare providers changed seismically with the onset of COVID-19. High and increasing infection rates resulted in many clinicians and care staff across both healthcare sectors working alongside suspected or confirmed COVID-19 patients.

3.2 Whilst the PHA and its UK counterparts issued initial guidance on PPE requirements for COVID-19 in January 2020, this has frequently changed during the pandemic to reflect updated scientific evidence. However, this caused confusion amongst both healthcare staff and providers, and presented considerable difficulties in planning for both the volume and type of equipment required. Appendix 1 assesses this area in greater detail, but revised guidance issued in April 2020 had particular significance, as it recommended using enhanced PPE, including aprons, gloves, surgical masks and eye protection, in most clinical and care scenarios. Staff performing Aerosol Generating Procedures (AGPs) were directed to use higher protection, including disposable gowns, filtering respirators and face visors. Updated guidance was also issued on PPE requirements for ambulance staff and paramedics.

3.3 As a result, demand for PPE among healthcare providers, which had already begun rising in early 2020, substantially increased. The need for higher volumes of existing equipment and new types of PPE was largely new and unforeseen. IHCP highlighted how a typical ICS homecare service provider’s monthly usage of aprons and gloves increased by 118 per cent and 190 per cent respectively, alongside a new monthly requirement for 27,000 Type IIR facemasks and 3,000 face visors. DoH decided in mid-April 2020 that all ISPs would be routinely provided with PPE free of charge through the BSO PaLS supply chain until further notice. However, supplying the large HSC and ICS workforces with increased volumes and new types of PPE presented obvious challenges.

Concerns arose over PPE supply and availability shortages in the early stages of the pandemic

3.4 When the pandemic was still in its early stages in March 2020, DoH was already acknowledging that significant issues existed with local PPE supply and availability. In correspondence with HSC organisations, it stated that it was seeking to resolve these, and attributed them to unprecedented global demand, combined with a manufacturing slowdown in affected countries, particularly China, as the largest scale PPE manufacturer

3.5 Our stakeholder consultation strongly indicates that supply shortages existed across the local healthcare system at this time. The RCN stated that many of its members across HSC and community and social care had raised significant concerns throughout March 2020 over PPE availability, particularly for FFP3 masks, and over the standard of some equipment. Although acknowledging that challenges then existed in securing PPE, it believes that it was simply unavailable in the required quantities, highlighting that it had repeatedly raised the need for intervention with DoH and other HSC organisations.

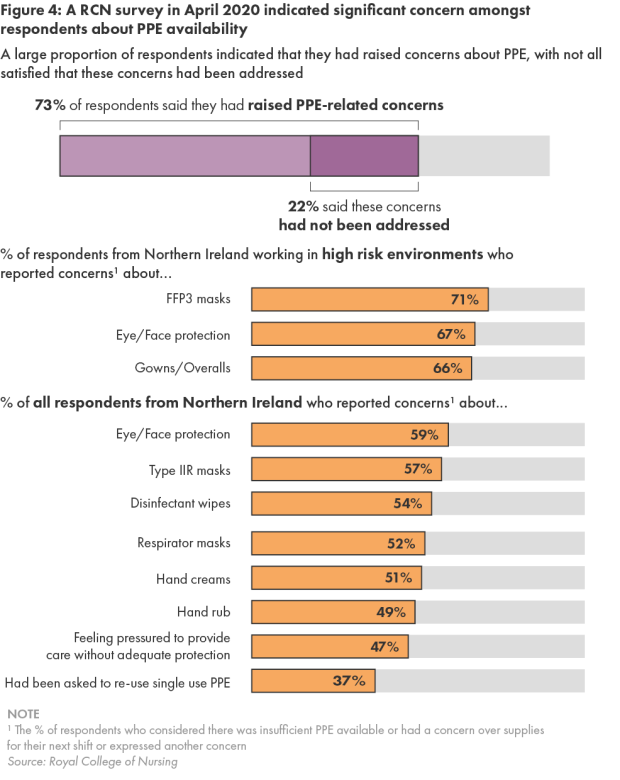

3.6 The RCN stated that it was still formally raising concerns over supply and availability during April 2020, primarily but not exclusively in nursing and residential homes. An April 2020 UK-wide RCN membership survey found that between 66 per cent and 71 per cent of NI respondents working in high risk environments (including carrying out AGPs) believed there was either insufficient supplies of key PPE items, or had concerns over supplies for their next shift, with between 49 per cent and 59 per cent of all local respondents expressing such concerns. Some 73 per cent had also raised concerns over PPE, and 47 per cent had felt obliged to provide care without adequate PPE protection (Figure 4) . Whilst surveys like this may not provide a fully representative view of the workforce, this still represented the largest exercise of this type completed during the pandemic.

3.7 IHCP stated that ISPs also had inadequate PPE supplies in the early stages of the pandemic, with particular shortages of FFP3 masks and eye protection. It told us that it made “considerable representations” during February 2020 and March 2020 to DoH about PPE shortages, but that the Department had maintained that procurement primarily rested with ISPs. DoH acknowledges that discussions with ICS representatives took place in March 2020, during which issues associated with access to PPE were raised.

3.8 Guidance issued by DoH on 12 March 2020 stated that “Independent providers are responsible for sourcing their own PPE equipment. However, in the event that they are unable to source the appropriate items HSC Trusts have been asked to ensure they work closely with independent providers to ensure they have the appropriate equipment available to them if suspected or confirmed cases of COVID-19 arise”. Further Departmental guidance on 17 March 2020 stated that whilst ISPs were required to work with suppliers to secure adequate PPE supplies, Trusts would provide support where they were unable to source items. At that time, the core-UK public heath guidance (paragraph 3.2) stipulated that standard PPE (aprons and gloves) was sufficient to protect ICS staff from COVID-19, and that enhanced equipment was not required.

3.9 Whilst some ISPs were clearly being issued with PPE through the public sector supply chain in March 2020, IHCP maintains that, at this stage, Trusts were only providing small supplies to care homes when a COVID-19 outbreak had occurred. It considers that these arrangements did not properly address the wider ICS supply shortages, or adequately satisfy public safety interests. It also stated that DOH officials had questioned payment arrangements for any PPE which might be supplied to ISPs. In the absence of central supply protocols, IHCP stated that shortages meant some care homes had to make their own PPE, or make appeals for equipment, and some had received donations from the community, charitable and commercial sectors.

3.10 In response to the emerging concerns, DoH commissioned a `rapid review’ of PPE-related issues on 15 April 2020. Published on 28 April 2020, this acknowledged that “staff have reported a lack of confidence in the system to ensure PPE stocks will be available in the right amounts”, and that “overall confidence in PPE supply is low”. Perhaps most significantly, it concluded that “there are shortages of PPE stock in the system, particularly long sleeve gowns and certain types of masks”, but more positively highlighted that “many have reported that over recent weeks the system has been improving and becoming more reliable”.

3.11 The review also found that overall satisfaction levels of end users varied from only four out of ten among ICS nursing and residential homes to seven out of ten for the Trusts, NIAS and ICS domiciliary care providers. Whilst stakeholders highlighted positive areas, including a coordinated ordering and supply approach, the consensus was that challenges remained, particularly around supply and availability, timeliness of supply, quality of PPE, the need for regular fit-testing of FFP3 masks, and for clearer guidance.

Significantly increased demand meant that PPE stocks remained very low until June 2020

3.12 Assuming lead responsibility for sourcing PPE presented BSO PaLS with considerable logistical challenges, particularly in developing robust modelling and forecasting of PPE requirements for COVID-19. Without any firm knowledge at the start of 2020 over if or when the virus would arrive in Northern Ireland, it adopted a precautionary approach on 27 January 2020 to increase its PPE stockholding from 4 weeks to 12 weeks BAU supplies, based on existing (pre-COVID) demand. It emphasised that there was no available information at this stage on likely demand in respect of COVID-19, or how long PPE stocks would last.

3.13 BSO PaLS was able to ensure a 12 week BAU situation by early February 2020, as PPE stocks had been bolstered in preparation for EU exit. However, the unprecedented demand levels which subsequently emerged in the context of COVID-19 meant that even this significant increase would have equated to under one week’s PPE provision.

3.14 Unsurprisingly, it was becoming apparent throughout February 2020 that BSO PaLS’ existing contractors had insufficient PPE to meet the HSC sector’s growing needs. Concerns were also then emerging that inadequate centralised control was enabling HSC staff to over-order PPE in anticipation of demand, particularly for FFP3 masks. BSO PaLS informed the Trusts of excessive ordering on 19 February 2020, highlighting that supplies of the brand leader’s FFP3 masks had become exhausted, albeit that alternative models remained available.

3.15 It is difficult to fully determine whether ordering levels in this period reflected stockpiling or a genuine increase in demand, or a possible combination of both. Compared to the stable pre-COVID demand, PPE units issued by BSO PaLS increased by 67 per cent in March 2020 compared to the previous month. The particular supply challenges with FFP3 masks arose because BAU supplies held by BSO PaLS equated to a relatively small number of items. Prior to the pandemic, BSO PaLS carried only one FFP3 model which had a high fit-test rate across the HSC. However, the supplier of this model ceased its production during the pandemic, meaning that BSO PaLS ran out of stocks for a short period and needed to source alternatives, including from Emergency Planning stockpiles. With this came the need for new fit-testing arrangements in HSC Trusts. BSO PaLS highlighted that it always had access to such alternatives.

3.16 Increased demand and supply constraints meant that BSO PaLS struggled to build sustainable PPE stocks in the early months of the pandemic. When the first wave began impacting in March 2020, it held just over 16 million core PPE items, with gloves accounting for 90 per cent of these, and it had no BAU stocks of fluid repellant gowns or visors as there was very limited demand for these among healthcare providers prior to the onset of COVID-19. Supplies of aprons, Type IIR masks and FFP3 masks were also very low. Compared to the average demand experienced during the pandemic at April 2021, we estimate that around one week’s supply of aprons was available, with stocks of all other items apart from gloves falling below this (Figure 5) .

3.17 By mid-April 2020, the Trusts and BSO PaLS collectively held 28.5 million core PPE items, but this reduced further to 22.2 million items by mid-May 2020, with BSO PaLS only holding 12.4 million items. Whilst this partly reflects that BSO PaLS had begun despatching PPE to Trusts within 24 hours of receipt, overall supplies were still limited, given the demands of COVID-19.

In response to high demand and supply constraints, BSO PaLS introduced demand management arrangements in late March 2020

3.18 Whilst increased ordering was significantly depleting its stocks, BSO PaLS continued operating a demand-led supply system for PPE throughout most of March 2020. However, increasingly conscious of its unsustainability for managing supplies during a pandemic and its growing impact on wider HSC availability, the Chief Pharmaceutical Officer, on the basis of advice from BSO PaLS, directed it to introduce demand management arrangements on 23 March 2020. From that date, BSO PaLS commenced “pushing” allocations of available PPE centrally to Trusts, who assumed responsibility for deploying supplies in a way which attempted to improve prioritisation and prevent hoarding.

3.19 Implementing this new system presented further challenges. It could not initially attempt to match BSO PaLS supply with demand, and daily liaison with the Trusts was required to agree supply levels based on balanced consideration of need and availability. To try and align limited supply as best as possible with increasing demand, BSO PaLS initially introduced allocation arrangements, based on its existing warehouse arrangements before adopting a population and Intensive Care Unit bed based approach in April 2020. It also began despatching PPE from its warehouses to Trusts within 24 hours of receipt, instead of operating its normal cycle-based approach.

3.20 Trusts also had to assume new responsibilities, including:

- storing and managing items where supply exceeded immediate Trust demand;

- managing distribution across their organisation;

- becoming the focal point for all PPE queries;

- establishing ordering systems for internal customers, systems of receipting, and responding to orders;

- developing daily stock check systems; and

- deciding how best to spread PPE supply across users.

3.21 As such, Trusts had very little time to establish local manual ordering, storage and distribution systems and facilities. BSO PaLS acknowledges that there was little evidence that this requirement was clearly articulated to, or well understood, by Trusts in the early stages of these arrangements, but told us that Trusts had mainly established the broad capability required within a few weeks.

UK-wide contingency arrangements for an influenza pandemic provided limited PPE support for COVID-19

3.22 In addition to introducing demand management arrangements, DoH was able to draw on PPE stocks held within a wider emergency stockpile of products which has been held in NI as part of UK-wide contingency planning for a significant influenza outbreak, established by the Department of Health and Social Care (DHSC) in 2011. This is known as the Pandemic Influenza Preparation Programme (PIPP) stockpile.

3.23 As central co-ordinator of the UK-wide arrangements, DHSC solely determines the type and volume of products held in the stockpile, but DoH has ownership and authority to release items, and BSO PaLS provides a storage, maintenance and stocktaking service. At February 2020, the stockpile included 19.8 million core PPE items, including 6.8 million Type IIR masks, 4.7 million aprons, and 4.7 million gloves. In addition, NI was the only part of the UK which held a small stockpile of surgical gowns (almost 800,000), as DoH had purchased these in 2009 in preparation for swine flu, and their long shelf life meant they remained usable, and could be consolidated into the local stockpile.

3.24 Whilst stockpile levels reflected estimated requirements for an influenza pandemic, PPE would be used significantly faster and in much greater quantities for COVID-19. For example, whilst the stockpile held just under 20 million core PPE items, BSO PaLS has delivered an average of 33 million items to local healthcare providers every four weeks during the pandemic. Therefore, whilst it provided a useful buffer, the stockpile had limitations in assisting the very considerable requirements for COVID-19. Reports by the National Audit Office and Audit Wales have arrived at broadly similar conclusions.

3.25 Where shortages of particular PPE items were imminent in BSO PaLS’ existing stocks, DoH provided authorisation for these to be released from the PIPP stockpile during the pandemic. Initial approval was provided in March 2020, and by late April 2020, DOH was acknowledging that although regarded as a “last resort” product source, some items had already become quickly depleted. However, it also recognised that greater access to the stockpile was required, to help avoid sporadic shortages which were undermining confidence in supply.

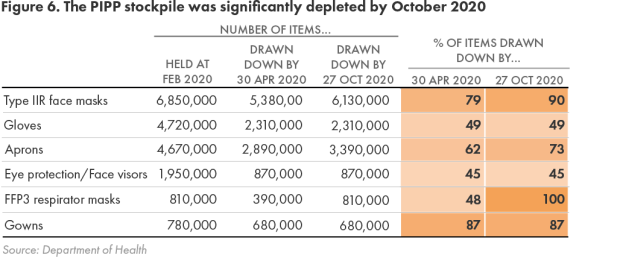

3.26 The continuing need to access the stockpile left it significantly depleted. By the end of April 2020, 12.5 million items (63 per cent of available stocks) had already been drawn down, including all available face visors. Some 190,000 pieces of eye protection were also withdrawn in June 2020, having been deemed to offer inadequate protection. By October 2020, when the final release was approved, 14.2 million items (almost 72 per cent) had been issued, including the entire stock of FFP3 masks, and almost 90 per cent of available Type IIR masks and gowns (Figure 6).

3.27 The relatively modest stockpile clearly helped plug early supply and availability gaps. However, PPE stocks are currently below DHSC recommended 15-week levels for an influenza pandemic due to both the significant drawdowns made for COVID-19, and previous procurement delays in 2019 which occurred whilst awaiting recommendations of work by the New and Emerging Respiratory Virus Threats Advisory Group. DoH told us that DHSC has commenced updated analysis on emergency preparedness for pandemics and High Consequence Infectious Diseases, which will ultimately inform future recommended PIPP stockpile levels and the logistics required to deliver effective contingency response arrangements.

3.28 In addition to the PIPP stockpile, DHSC also developed `Just in Time’ (JIT) arrangements in 2011 which aimed to establish flexible emergency procurement arrangements for required products. DHSC activated JIT contracts in early 2020, with around 340,000 items, including hand hygiene, syringes, and clinical waste products, being delivered to Northern Ireland in February 2020 through these. However, no core PPE items were provided. Around this time, DHSC had initiated JIT contracts for the supply of 6.8 million FFP3 masks, but cancelled this order due to concerns over the supplier’s ability to fulfil it. BSO PaLS told us that DHSC’s JIT arrangements had not proved as successful as anticipated in meeting the surging demand for PPE experienced during the pandemic. In April 2021, Audit Wales attributed the limited impact of the JIT contracts to global market supply difficulties.

The scarcity of PPE in the early stages of the pandemic means that mutual aid across the UK was limited

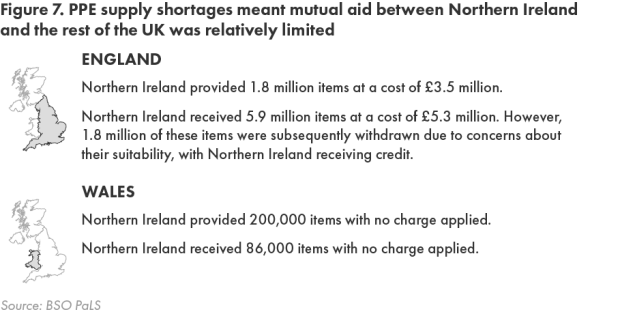

3.29 Whilst mutual aid between the four UK nations provided a further potential means of sourcing PPE, the scarcity of supply meant that this was limited and largely confined to the earlier stages of the pandemic. In total, NI has received just over 5.9 million PPE items, mainly from England, and provided just under two million items to England and Wales (Figure 7) .

3.30 DoH told us that when mutual aid had been available, it had supported NI in meeting supply challenges. However, it acknowledged that the limited UK supply situation had presented difficulties. Its April 2020 review of PPE issues (paragraph 3.10) stated that “the difficulty in relation to COVID-19 is that none of the nations have much stock to provide each other under mutual aid, the principles are more easily applied when there are adequate supplies”.

Healthcare providers received more sustainable deliveries as supply pressures eased, and BSO PaLS had distributed almost 500 million core PPE items by mid-2021

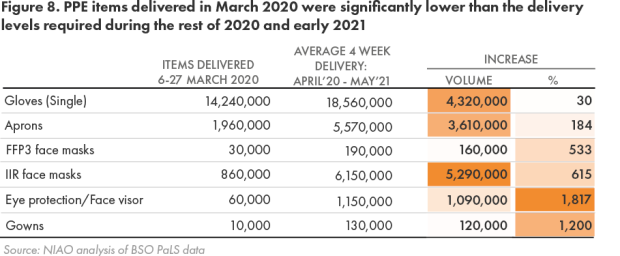

3.31 Data reported by BSO PaLS tends to confirm early PPE supply shortages. The 17.2 million core PPE items it delivered in March 2020 was 46 per cent lower than the average of almost 32 million items in subsequent four-week delivery periods up to May 2021, and significantly lower volumes of all items were provided (Figure 8) .

3.32 Following March 2020, subsequent four-week deliveries increased significantly, and these ranged between 26.3 million items and 44.3 million items. In addition to an improved supply situation, key changes to the PPE guidance in April 2020 (Appendix 1 paragraph 3 ) and the decision to supply the ICS and primary care providers with PPE likely contributed to the increased volume of equipment supplied. In total, BSO PaLS has delivered 498 million core PPE items between March 2020 and May 2021(Figure 9) .

3.33 BSO PaLS has also delivered 7.9 million `covid impacted’ items between March 2020 and May 2021 (Figure 10 ).

3.34 Compared to the limited PPE stocks held in the earlier stages of the pandemic, levels had increased very significantly by July 2020, with BSO PaLS and the Trusts collectively holding 132 million items and BSO PaLS having augmented its stocks to 124 million items (Figure 11) .

3.35 As the supply situation started improving from mid-2020, BSO PaLS has also progressively sought to restore central ordering arrangements for those PPE items initially subject to supply pressures. However, Trusts remain responsible for co-ordinating the supply and distribution of products which are still subject to demand management.

3.36 As data on PPE provided to the ICS is unavailable prior to mid-April 2020, support levels provided in the earliest stages of the pandemic cannot be accurately identified. However, available information shows that ISPs received 1.7 million core and COVID-impacted items in the week ending 11 April 2020. In total, they were allocated over 175 million items through the BSO PaLS supply chain between mid-April 2020 and July 2021, which had a total estimated value of £56.13 million (Figure 12).

The supply situation had improved considerably by late April 2020 with effective distribution arrangements established, but stakeholders consider they had to lobby extensively to achieve this

3.37 Following the significant earlier concerns, the RCN told us that PPE supply arrangements had been considerably strengthened by late April 2020. A follow-up membership survey by RCN in May 2020 also indicated that UK-wide supply was matching demand more closely, although 54 per cent of respondents working in high risk areas still had concerns over supplies of FFP3 masks.

3.38 Pressures within the ICS had also notably eased by this stage. Key factors behind this included each Trust establishing Single Points of Contact to liaise with ISPs on PPE issues by mid-April 2020, and the Department’s decision at this time that all ISPs would be routinely provided with PPE free of charge via Trust distribution systems. Whilst IHCP told us that initial glitches with these systems led to some further delays, it stated that ISPs were receiving adequate supplies by mid-April 2020. Arrangements introduced in April 2020 for daily RAG status reporting by all care homes to Trusts on PPE supplies have identified no red status cases, and “very few” amber cases, where Trusts have taken steps to mitigate concerns reported. Such monitoring did not exist in February and March 2020, when IHCP maintains there were significant sectoral PPE shortages.

3.39 IHCP considers it had to lobby extensively for the initial supply problems to be resolved, highlighting particular difficulties in convincing HSC bodies of the complexity of nursing home care, including the need for FFP3 masks to perform AGPs. It holds the view that increased supplies were only provided when COVID-19 cases in care homes began escalating, and stated that many existing ICS suppliers had told ISPs that they had been instructed by central government to `ring fence’ their PPE supplies for HSC use. In providing evidence to the House of Commons Public Accounts Committee in December 2020, witnesses in England expressed similar concerns.

3.40 In attempting to secure adequate PPE, the unparalleled increase in demand which BSO PaLS has had to deal with must be acknowledged. Compared to 2019, demand has risen by: 427 per cent in overall terms; almost 16,500 per cent for eye protection and face visors; and by 3,700 per cent and over 4,300 per cent respectively for FFP3 masks and Type IIR masks (Figure 13) .

3.41 In addition to helping healthcare providers build up substantial PPE stocks, BSO PaLS has encountered other demand-led issues, including various spikes in COVID-19 transmission rates, equipping community pharmacies to deliver seasonal flu vaccinations, and ensuring availability of adequate stocks during holiday periods. Notwithstanding the early supply and availability issues, evidence indicates that healthcare providers’ PPE needs have mainly been met since late April 2020. As such, BSO PaLS has largely established effective supply and distribution arrangements since that date.

3.42 We recognise the commitment and work undertaken in very challenging circumstances by staff in DoH, BSO PaLS, HSC Trusts and other bodies to procure, store and distribute PPE throughout the pandemic.

Part Four: Costs and procurement methods

The severe disruption of supply chains meant that BSO PaLS had to quickly identify new supply sources

4.1 Establishing reliable supply arrangements has been problematic, given the significant supply continuity problems during the early stages of the pandemic. BSO PaLS experienced interruptions and delays to its established contracts, which also proved insufficiently resilient to provide reliable supplies. Some existing suppliers could not maintain contractual supplies of Type IIR masks and face visors until late Summer 2020, by which time their prices had risen. Contracted levels of gloves and aprons were insufficient to meet the increased demand, and the delivery of aprons was also delayed. In one case, a supplier was unable to make any deliveries on an order for 50,000 FFP3 masks placed in Spring 2020, until Spring 2021.

4.2 BSO PaLS therefore needed to quickly identify new supply sources. It followed up over 2,000 potential leads to varying degrees of success in the initial months of the pandemic, engaging with both known and potential sources, and suppliers who had contacted government bodies offering assistance. Following assessments of the availability and suitability of products, pricing terms and lead times, BSO PaLS engaged 45 suppliers between January 2020 and April 2021, either with whom it had no previous business relationship, or from whom it had not previously procured PPE.

4.3 Many of these suppliers were new to the PPE market, meaning their ability to fulfil large scale orders of suitable equipment within tight deadlines was untested. This part of the report examines the costs incurred, procurement methods deployed, and risks in these areas in greater detail. However, at a high level, the 45 new suppliers BSO PaLS contracted with have notably assisted its efforts to secure the required PPE, with orders for almost 618 million core PPE items placed with these suppliers between January 2020 and April 2021.

Almost £400 million was spent up to April 2021 on procuring PPE for local healthcare providers

4.4 Purchase orders raised through contracts signed during the pandemic provide the best indicator of both the number of PPE items ordered and total expenditure incurred. Whilst BSO PaLS has procured the vast majority of PPE purchased for healthcare providers, DoH also signed a £٦٠ million contract with a Chinese supplier in April 2020. Between January 2020 and April 2021, BSO PaLS and DoH ordered 1.3 billion core PPE items, at a total cost of £397million (Figure 14) . Collectively, aprons, gloves and Type IIR masks represent 96 per cent of items ordered, and 73 per cent of costs.

4.5 In addition to these purchases, Trusts procured just under £0.7 million worth of PPE between March 2020 and October 2020. BSO PaLS has also continued purchasing FFP3 masks from DHSC through National Health Service Supply Chain framework contracts during the pandemic, spending just under £0.1 million on these in 2020.

4.6 Compared to the annual pre-pandemic spend on PPE of less than £3 million, the £400 million spent to date during the pandemic again starkly illustrates the degree to which reliance on this equipment has increased.

The Cabinet Office approved the use of emergency regulations to procure PPE without competition

4.7 Direct Award Contracts (DACs) occur when a contract is let without competition, or where an existing contract is materially changed. They are mainly used when there is insufficient time to conduct a full procurement process. Whilst a DAC can be let above or below the European Union’s (EU’s) prescribed estimated value threshold, Northern Ireland Public Procurement Policy requires convincing reasons even for contracts falling below this threshold, such as overriding public interest circumstances.

4.8 Regulation 32 of the Public Contracts Regulations 2015 broadly permits DACs with an estimated value above the EU Threshold to be awarded where genuine reasons exist for extreme urgency, and where events leading to this were unforeseeable. Guidance issued by the Cabinet Office on 18 March 2020 confirmed that these `emergency regulations’ could be used to procure PPE during the COVID-19 pandemic. Prior to this, BSO PaLS had only purchased PPE through DACs in a small number of exceptional cases.

BSO PaLS has been very heavily reliant on untendered contracts to procure PPE

4.9 BSO PaLS began procuring core PPE and COVID-impacted items through relatively small value DACs in February and March 2020. Since then, it has been very heavily reliant on DACs to purchase high volumes of PPE within tight timescales during the pandemic. Between February 2020 and November 2020, BSO PaLS provisionally awarded 70 DACs with values above the EU threshold for core PPE alone, including 20 with estimated values of between £10 million and £50 million. These contracts, together with the DoH-led procurement (paragraph 4.4) which was also let as a DAC, had a total initial estimated value of £549 million.

4.10 Although most of these contracts will proceed to award, actual expenditure will fall below initially approved levels, as BSO PaLS may not need to fully draw down on these, and some contractors may also be unable to fully meet supply requirements. Figure 14 shows that purchase orders with a total value of £397 million were raised for core PPE items up to April 2021. Some £25.7 million of this relates to competitive contracts for the supply of gloves, let in February 2021. BSO PaLS stated that the majority of the remaining £371.3 million relates to procurement made through DACs. This could increase if further purchase orders are raised under these contracts, but will not reach the full approved level of £549 million. Overall, this demonstrates how heavily reliant BSO PaLS has been on non-competitive procurements for PPE during the pandemic. This is consistent with a similarly high reliance on such contracts to procure PPE across the rest of the United Kingdom.

Urgency of need meant a large number of high cost short-term Direct Award Contracts were approved in the early stages of the pandemic

4.11 The urgent situation meant that procurement activity was particularly intense in April and May 2020, and up to July 2020, BSO PaLS mainly entered into `one-off’ type DACs, involving a single or small number of deliveries over a short period, to ensure immediate supplies. These contracts were agreed during the early “high cost” stages of the pandemic, when shortages were most acute, and when there was significant market cost inflation. Fuller details of this cost inflation are outlined at paragraphs 4.22 to 4.28, but during this period, average prices for gloves, gowns, and Type IIR masks were up to 735 per cent, 957 per cent and 1,314 per cent higher respectively than pre-COVID prices.

4.12 As market rates started falling and the supply situation began improving in May and June 2020, BSO PaLS was able to negotiate prices downwards. For example, whilst unit costs of Type IIR masks ranged between £0.38 and £1.88 under the early high cost contracts, they reduced to between £0.25 and £0.50 in longer-term `period’ contracts subsequently agreed. In August 2020, BSO PaLS approved 11 such DACs with a total estimated value of almost £180 million, including four of the highest value contracts signed to date, ranging in value from £30.5 million to £50 million. Although these contracts did not contain clauses for further negotiating prices downwards, BSO PaLS considers that they provided competitive pricing when signed, and were awarded for a period of no longer than 12 months.

BSO PaLS made advance payments of £26 million to suppliers to secure PPE, and is currently trying to recover £0.9 million from a supplier for an unfulfilled order

4.13 Prepayments involve a contracting authority paying for goods or services before they are delivered. Prior to the pandemic, BSO PaLS did not need to make any prepayments for PPE, but the difficult supply environment which developed meant that some suppliers began insisting on full or partial prepayment before accepting orders. In May 2020, DOH provided BSO PaLS with approval to make prepayments for PPE, and BSO PaLS revised its prepayment framework, requiring authorisation by various senior staff. A September 2020 Internal Audit (IA) review concluded that these changes were reasonable.

4.14 Between May 2020 and September 2020, BSO PaLS placed 31 orders for PPE with a total value of £132.3 million, approving full or partial prepayments totalling £26.3 million to suppliers.

4.15 However, in one case, a supplier who received an upfront payment of approximately £0.88 million (50 per cent) failed to deliver an order for 2.5 million Type IIR masks, having offered an unsuitable replacement product. BSO PaLS had conducted no previous business with this supplier, and had identified it as high risk prior to contract signature. Following several unsuccessful attempts to resolve its concerns, BSO PaLS commenced legal action in November 2020 to recover this prepayment. The improved supply situation means that it has not had to make any prepayments since August 2020.

The overriding need to secure PPE meant that BSO PaLS had to engage high risk suppliers

4.16 For its longer-term pre-pandemic PPE contracts, BSO PaLS completed pre-award checks on bidders’ financial and operational standing. As DACs let during the pandemic were mainly shorter-term agreements, it did not undertake any due diligence checks on suppliers not requesting prepayment, but only paid for goods after received and inspected for quality. If suppliers requested prepayment, BSO PaLS checked their trading history, and allocated them a risk rating before placing orders. In total, six suppliers, including the company BSO PaLS has initiated legal action against (paragraph 4.15) were identified as high risk. The urgent need for PPE meant that BSO PaLS placed orders with these six suppliers, although it terminated a contract with one supplier due to concerns over the veracity of its offer.

4.17 Aside from this case and the prepayment which BSO PaLS is trying to recover, no significant problems were experienced with the other high risk suppliers. However, the September 2020 IA review (paragraph 4.13) highlighted several issues with how they were engaged, including the fact that no additional internal approval was secured in these instances. It also identified risks around multiple prepayments made to the same suppliers, and inadequate risk assessments on suppliers requesting prepayments. IA also identified scope for other improvements, including:

- an improved audit trail to evidence compliance with BSO’s Standing Financial Instructions and Managing Public Money Northern Ireland;

- enhanced reporting and scrutiny of prepayments and associated risks to, and by, BSO’s Senior Management Team and Governance & Audit Committee; and

- enhanced evidence of suppliers insisting on prepayments, tracking of delivery and receipt of orders, and of issues including non-delivery.

BSO PaLS published contract award notices for all DACs, but the required 30 day deadline was not met for seven contracts

4.18 The use of DACs has significantly assisted BSO PaLS in securing PPE. However, to help maintain public trust, bring transparency to the process, and prevent procurement decisions being challenged, public bodies must fully document their procurement decisions and actions for contracts let without competition, and publish their contract awards for DACs above the EU threshold in a timely manner.

4.19 The Cabinet Office stipulates that a contract award notice should be published within 30 days of a DAC being awarded. BSO PaLS told us that award notices have been published for all 48 DACs for core PPE items above the threshold which have progressed to award stage during the pandemic, but acknowledges that seven of these were published outside of the required 30 day period, due to the high volume of work facing the organisation at the time.

BSO PaLS told us that no conflicts of interest have been identified for PPE contracts awarded during the pandemic

4.20 Effective arrangements are also required for identifying and managing conflicts of interest (COIs) for contracts awarded without competition. In the context of the DACs awarded by BSO PaLS, the absence of competition, use of many new suppliers, including local companies, and the need to quickly agree and approve a large number of contracts, arguably increased the potential for COIs arising and not being identified.

4.21 For these contracts, BSO PaLS has relied on its existing arrangements for managing COIs, whereby staff involved in contract award decisions complete an annual third party transactions declaration, and did not consider it necessary to introduce any additional safeguards. It stated that “by and large”, new suppliers tended to contact BSO PaLS directly, or were identified by its staff through internet searches, no potential offers were `fast-tracked’, and all had to pass quality and specification assessments. To date, no BSO PaLS staff have declared any COIs. However, this process relies exclusively on relevant officials making declarations, and is therefore unlikely to detect any undisclosed conflicts. BSO PaLS told us that it followed existing guidance on CoIs during the pandemic, and no additional guidance was recommended or issued, but if this had been the case, this would have been applied.

A cost inflated market meant BSO PaLS incurred very high costs for all PPE items in the early stages of the pandemic until prices stabilised

4.22 Although PPE market rates began increasing in mid-February 2020, BSO PaLS told us that it had continued trying to source at best price, but that the very limited availability of all items and significant and sustained price increases presented it with considerable difficulties. In the prevailing circumstances, BSO PaLS acknowledges that continuity of supply quickly became its main consideration in procurement decisions.

4.23 Unsurprisingly, BSO PaLS incurred substantially higher costs during the first wave of infections compared to early 2020 prices. Average prices peaked between April 2020 and June 2020, with particularly high increases for gloves (733 per cent), gowns (957 per cent) and Type IIR masks (1,314 per cent). Whilst prices began reducing notably in the later stages of 2020, they still remained higher than pre-pandemic costs (Figure 15) .

4.24 BSO PaLS referred 60 examples of cost inflation to the Competition and Markets Authority in May 2020. These cases involved prices which were between 60 per cent and 1,282 per cent higher than pre-COVID contract rates, with the suppliers invariably attributing these to global supply shortages (Figure 16) . BSO PaLS proceeded with these orders to secure required equipment, raising purchase orders of almost £127 million with these suppliers. BSO PaLS faced a number of difficult decisions. For example, it told us that it had paid almost 1,300 per cent higher for Type IIR masks than contractual rates, as it urgently required supplies and the contractor could guarantee quick delivery.

4.25 Prices paid for gowns in April 2020 varied significantly. Whilst BSO PaLS procured these on 13 April 2020 for £0.68 and £1.24 each, costs increased to between £4.87 and £5.85 between 14 April 2020 and 29 April 2020, with a 760 per cent variance apparent between the lowest and highest rates. At this time, BSO PaLS highlighted that PPE supplies were very restricted, with daily price changes reflecting both availability pressures and significant changes to guidance on PPE requirements (Appendix 1 ). It told us that it had declined a supplier offer at this time for gowns priced at £15 each.

4.26 The 3.4 million gowns which BSO PaLS ordered in April 2020 at the higher market rates have proved more than sufficient to meet local needs, with two million having been distributed to healthcare providers by the end of May 2021. BSO PaLS has also not had to order any further supplies since April 2020. Whilst uncertainty existed over both future requirements and availability at this time, it is clear that BSO PaLS ordered a very large volume of gowns at high market prices. In May 2020, the comparable shared services organisation in Wales procured three million gowns at unit costs of £2.50.

4.27 Although all PPE items were difficult and expensive to source up to May 2020, BSO PaLS has encountered particular difficulties in procuring FFP3 masks, due to their very specialist nature, and because the global brand leader has been allocating fixed stock levels, instead of supplying volumes actually required. Where other providers were offering this item, it was often over 100 per cent more expensive, and in many cases, was fake, or unsuitable for clinical use.

4.28 The ICS also experienced significant price rises during 2020:

- A Health and Social Care Board memo (9 April 2020) highlighted that ICS suppliers were charging up to eight times the normal prices for gloves, aprons and hand sanitiser, with some stating this additional cost was potentially threatening their medium term viability.

- IHCP highlighted progressive price increases between January 2020 and September 2020 for 100 gloves, from £1.55 to £7.95 (412%), with 200 aprons increasing from £2.95 to £6.95 (136%) in broadly the same period. It believes that the increased volume of PPE required, alongside significant price increases, could have placed many ISPs under significant financial strain had DoH not introduced free of charge provision.

BSO PaLS did not fully document decisions to proceed with high cost procurements

4.29 The emergency regulations provided BSO PaLS with full authority to use DACs to procure PPE, provided these were approved by its Chief Executive. On occasions, operating in a volatile market meant that this approval was provided verbally or by email, but BSO PaLS stated that this was very quickly supported by formal approval. In its September 2020 review however (paragraph 4.13), IA highlighted a need for stronger documentary approval evidence for PPE related DACs.

4.30 BSO PaLS told us that supplier prices during the pandemic have been benchmarked with prevailing PPE market rates, and that where these varied “considerably”, its COVID-19 Steering Group reviewed and discussed these before Chief Executive approval to proceed with a DAC was sought. Whilst it told us that it only sought approval for such purchases where supply was in jeopardy, it acknowledges that this process was not documented.

4.31 Fuller documentary evidence would have provided a more complete record and trail of important procurement decisions taken during the pandemic. Although government bodies were procuring goods and services at speed, standards governing procurement practices still applied. For example Regulation 84 of The Public Contracts Regulations 2015 states that awarding bodies should document the progress of all procurement procedures, and retain sufficient documentation to justify decisions taken. This applies to all procurements, including DACs let under the emergency regulations. BSO PaLS considers that documentation completed in relation to the award of the DACs meets the requirements of these Regulations.

Benchmarking suggests BSO PaLS paid higher prices for some PPE items than Wales in the early stages of the pandemic

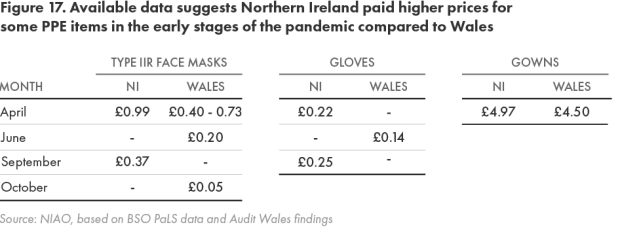

4.32 Comparing local procurement costs with the rest of the UK is difficult, due to differing product specifications and the highly fluctuating market. However, available data for average costs suggests that BSO PaLS paid higher prices during the early stages of the pandemic for several PPE items than costs incurred in Wales (Figure 17 ). BSO PaLS highlighted that Northern Ireland typically incurs additional transportation costs, and that the volumes purchased by each nation may also impact on costs.

Part Five: The quality of PPE supplied and guidance, training and instruction in its use

Issues have arisen over the availability and quality of fit-testing of FFP3 masks

5.1 In addition to ensuring sufficient availability, BSO PaLS has had to source PPE of the required specification and quality. This has again presented some problems. In March 2020, the RCN expressed concerns to the Health and Safety Executive Northern Ireland (HSENI) that the fit-testing of FFP3 masks was widely unavailable, creating the risk that ill-fitting equipment could increase infection risks. In its April 2020 members survey (paragraph 3.6), 29 per cent of respondents stated that they had not had a fit-test for their FFP3 masks.

5.2 Whilst BSO PaLS had commenced work on procuring fit-testing for FFP3 masks, it had not completed this by the time COVID-19 arrived in Northern Ireland, meaning Trusts had to individually award DACs for this service. DoH told us that a Serious Adverse Incident (SAI) investigation on the quality of Fit-testing at the start of the pandemic remains ongoing.

5.3 A review of fit-testing of FFP3 masks across the HSC sector and ICS in mid-2020 also identified that one contractor was sometimes inadvertently applying a fit-test setting not normally used in Northern Ireland. Of 41,771 fit-testing certificates reviewed, 2,886 staff (7 per cent) were identified as requiring re-testing. Various steps were taken to resolve safety concerns, including re-test programmes, local staff support helplines, and offering COVID testing to staff. A regional fit-testing framework is currently being developed to support standardisation across NI.

Wider concerns have been expressed over the quality of some PPE provided during the pandemic

5.4 In addition to fit-testing issues, the RCN’s April 2020 survey identified that a significant proportion of respondents were using donated, home-made or self-bought PPE (31 per cent for eye and face protection, 16 per cent for Type IIR masks and 19 per cent for FFP3 masks). IHCP told us that it had also received reports from a number of ISPs around the quality and validity of some PPE supplied, of Trusts recalling some supplies, and examples of masks being out-of-date, being re-dated, and of quality issues with manufacture and integrity of products.

5.5 The Department’s own April 2020 review of PPE issues (paragraph 3.10) acknowledged that in some instances, the quality of PPE had been unreliable. Feedback obtained from HSC sector and ICS stakeholders highlighted the “poor and unacceptable quality of some PPE supplies”, including a recent example where some HSC staff had deemed long sleeve gowns unsuitable for use. Recognising that quality had been a recurring theme across several PPE items, the review recommended the development of systems to enable feedback from end users, to help better inform future procurement decisions.

Innovative and collaborative working has helped ensure most PPE purchased meets the required specification and quality, but some concerns have still arisen

5.6 To try and ensure that PPE offered by new suppliers meets the required specification and quality, in March 2020, DoH asked BSO PaLS to work with the PHA’s Infection Prevention Control experts, Pharmacists based in the Medicines Optimisation Innovation Centre (MOIC), and HSENI, to develop suitable assessment arrangements. Since 1 April 2020, newly proposed PPE has had to pass a pre-procurement assessment by BSO PaLS, which includes:

- a MOIC-led technical review to ensure there are no inherent design risks or fraudulent presentation of certification standards;

- a physical wear test by PHA professionals to confirm suitability for use and that staff will not be exposed to risk through poor fit; and

- ensuring that FFP3 masks achieve a reasonable fit-test pass rate.

These arrangements were formalised into a `Product Review Protocol’ in March 2021.

5.7 By mid-May 2020, almost 600 proposed PPE items from 248 suppliers had been assessed, with 45 per cent being rejected for use, less than 17 per cent being approved, and 39 per cent still being assessed. Rejection rates were particularly high for the various types of facemasks examined (52 per cent), protective clothing items (36 per cent) and eyewear (38 per cent). However, two-thirds of gloves were approved for use (Figure 18) .

5.8 The high proportion of items rejected prior to procurement demonstrates the effectiveness of these validation processes. However, feedback from HSC staff still highlighted a need for further work to enhance the specification of some products approved for use, as these had exhibited practical deficiencies when used in clinical settings.

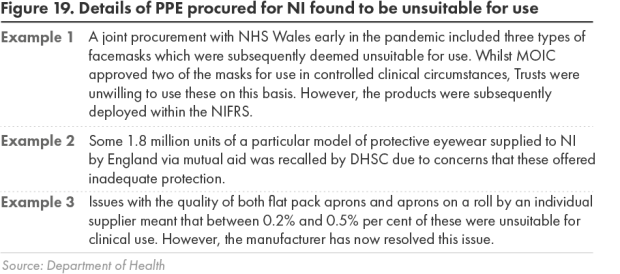

5.9 This further work, which is being overseen by MOIC and HSENI, is important, given that in some instances, PPE deployed locally has proved unsuitable, or fallen below the required standards (Figure 19) .

Healthcare staff have received training and instruction in the use of PPE, but the coverage achieved is unclear

5.10 The level of protection offered by PPE can also be significantly reduced if users are not provided with appropriate training on its use. Employers’ key legal responsibilities include ensuring employees using PPE are aware of why it is needed, when to use it, how it can be replaced, and knowing who to report any damaged equipment to. Employers are also required to train and instruct employees on the proper use of PPE, and ensure they are complying with this.

5.11 A range of initiatives during the pandemic has aimed to provide local healthcare staff with training on both Infection Prevention and Control (IPC) awareness, and on the use of PPE, including:

- PHA commissioning IPC training for HSC and ICS staff in 2020 and 2021, and developing and disseminating guidance on PPE required for different HSC settings, with various documents on its website, alongside DoH and NI Direct, providing access to the latest information;