List of Abbreviations

BLACMW Biodegradable Local Authority Collected Municipal Waste

BMW Biodegradable Municipal Waste

CCC Climate Change Committee

CDE Construction, Demolition and Excavation Waste

CEP Circular Economy Package

C&I Construction and Industrial Waste

DoH Department of Health

EEE Electrical and Electronic Equipment

EfW Energy from Waste

EPR Extended Producer Responsibility

DAERA Department of Agriculture, Environment and Rural Affairs

LAC Local Authority Collected

LACMW Local Authority Collected Municipal Waste

LACW Local Authority Collected Waste

MBT Mechanical Biological Treatment

NIEA Northern Ireland Environment Agency

NILAS Northern Ireland Landfill Allowance Scheme

NISRA Northern Ireland Statistics and Research Agency

RDF Refuse Derived Fuel

SRF Solid Recovered Fuel

rWFD Revised Waste Management Framework Directive

WEEE Waste Electrical and Electronic Equipment

WMPNI Waste Management Plan for Northern Ireland

WRAP The Waste and Resources Action Programme

WTN Waste Transfer Note

WTS Waste Transfer Station

Key Facts

Councils spent approximately £170 million on waste management in 2021-22

Northern Ireland’s next Waste Management Strategy is due to be published by DAERA in 2024

Northern Ireland has the second highest Waste from Households (WfH) recycling rate (48.4%) in the UK, compared to Wales (56.7%), England (44.1%), Scotland (41.7%)

Northern Ireland first met its 2020 EU target to recycle at least 50% of waste from households in 2019

Northern Ireland has a target to reach Net Zero by 2050

In Northern Ireland:

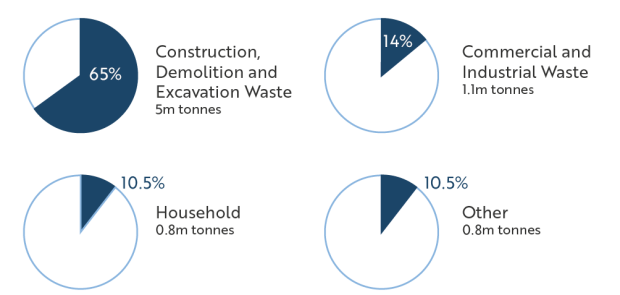

Approximately 7.7 million tonnes of waste is generated annually

Almost 1 million tonnes of household and commercial waste collected by councils in 2022-23

Approximately 65% of the total waste generated is Construction, Demolition and Excavation Waste

Executive Summary - Scope of the Report

The purpose of this report is to provide an overview of the waste management system in Northern Ireland, evaluating its current state, identifying key challenges, successes, and recommendations. By analysing the existing waste management infrastructure, regulatory framework and targets, this report aims to shed light on the progress made in the region and offer insight into how waste management practices could be improved.

This report aims to provide a fact-based analysis of waste management in Northern Ireland, offering recommendations to assist in the movement towards creating a circular economy that maximises resource efficiency and minimises waste generation.

Key Findings

DAERA has not produced a Waste Management Strategy since 2013.

1. An updated strategy was due to be published at the end of 2023 but is now expected to be published in 2024. DAERA held stakeholder engagement events in September and December 2022 to discuss the development of its new Waste Management Strategy. It is likely to contain a renewed focus on the importance of waste prevention and set new targets for the various types of waste.

2. DAERA’s last Waste Management Strategy was published in 2013. It set out the policy framework until 2020, building on the core principles of a previous 2006 strategy. DAERA published the closure report for the 2013 strategy in June 2022. Of the 27 actions and 17 targets included in the report, 22 were achieved, 10 were achieved beyond the target date, 4 were superseded or alternative actions taken, 3 were partially achieved, 4 were not achieved but improvements made and 1 was not achieved.

3. DAERA also published a Waste Management Plan for Northern Ireland in 2019 fulfilling the EU requirement that each state should establish such a document. However, this is a high-level document which does not act as a substitute for a Waste Management Strategy.

4. DAERA advised that due to resourcing constraints it had to pause work on the new Waste Management Strategy. Publication is delayed until 2024, with an exact date yet to be determined. A new Waste Management Strategy, with updated and clear targets, is important for all stakeholders in Northern Ireland. Achievements have been made against targets for some types of waste in recent years and this momentum needs to be sustained.

Recommendation 1

An updated strategy should be finalised and published by DAERA as soon as possible. The strategy should provide clear focus on future requirements to ensure that DAERA and other stakeholders are making timely, cost and resource effective decisions. The longer that a strategy is delayed the longer there is a sense of uncertainty for all stakeholders. We recommend that DAERA ensures that the waste targets set within the strategy are in line with other environmental targets, such as achieving net zero greenhouse gases by 2050.

There is an absence of long-term plans to prioritise waste prevention and to ensure that performance against waste prevention targets can be tracked.

5. Waste prevention is the preferred method of waste management which avoids generating waste in the first place. This is mainly achieved through measures addressing product design, packaging reduction and lifestyle changes that minimise waste production.

6. Councils have been collectively successful in meeting their recycling and landfill targets over recent years, although performance between councils has differed. Recycling rates steadily increased up to 2019-20, in 2020-21 there was a levelling off and then a slight decline in 2021-22. The quarterly provisional statistics for municipal waste for July – September 2023 show an increasing trend in recycling rates and bring Northern Ireland’s waste from household figures back up to pre-Covid levels (50.7 per cent).

7. The first Waste Prevention Programme for Northern Ireland was published in 2013 and proposed thirteen waste prevention actions. An updated programme was issued in 2019 which incorporated ongoing actions from the 2013 document and included twenty-two actions for DAERA. The waste prevention actions in the 2019 programme are not quantitative nor are they accompanied by indicators of performance to ensure all the relevant stakeholders are meeting their waste prevention targets.

8. A successful action from the 2013 programme was the Single Use Carrier Bags Charge Regulations (Northern Ireland) 2013. The subsequent 2019 programme noted that since implementation of this legislation, the levy had removed approximately 1 billion single use plastic carrier bags from circulation.

Recommendation 2

We recommend that DAERA continues to prioritise waste prevention within a new Strategy by setting clear and measurable targets for all stakeholders, as per the Waste Hierarchy.

DAERA, working with stakeholders, should ensure that Northern Ireland has sufficient infrastructure to process waste in line with future prevention, reuse, and recycling targets.

9. The Circular Economy Package (CEP) sets new targets for DAERA, including recycling 65 per cent of municipal waste and to landfill no more than 10 per cent of municipal waste annually by 2035. The circular economy refers to the continual use of resources and the minimisation of waste. It is anticipated that DAERA’s updated Waste Management Strategy will outline how future targets are to be met. In addition, there is a requirement from the Climate Change Act (Northern Ireland) 2022 to recycle at least 70 per cent of all waste by 2030.

10. Currently, there is only one energy from waste (EfW) plant in Northern Ireland, operated by a private sector provider in Belfast Harbour Estate. The plant can combust just under 160,000 tonnes of refuse-derived fuel annually. Refuse-derived fuel is created by processing different types of waste. Whilst EfW is considered environmentally preferable to landfill, it is still a carbon intensive process, and only waste that cannot be reused or recycled should be used in this process, in line with the waste hierarchy.

11. NIEA currently regulates a total of 47 anaerobic digestion facilities in Northern Ireland; waste and farm fed licenses (42) and Pollution Prevention and Control (PPC) Permits (5). Waste-fed anaerobic digestors used municipal, commercial, and industrial waste as feedstock. Most of the biogas generated is used for on-site combined heat and power and the surplus electricity is sold for export.

12. A recent project proposed developing a £240 million energy from waste (EfW) plant and recycling facility at Hightown Quarry in County Antrim (Becon, 2023). This has been subject to legal proceedings for almost a decade but in May 2023, the high court quashed the most recent decision to deny planning approval for building the plant. Planning approval will now, again, be considered by the Department for Infrastructure. The facility could provide substantial additional processing capacity for local black bin waste (an anticipated 250,000 tonnes annually).

Recommendation 3

We recommend that DAERA works to ensure that the pathway to meeting future environmental targets is facilitated by the development of appropriate infrastructure, through engagement with waste and environmental experts and stakeholders.

Just over 990,000 tonnes of waste was recorded as having been exported from Northern Ireland in 2023, including waste from councils and businesses.

13. Local councils primarily export waste for recycling and energy recovery, via contracted waste processors. In 2021-22 and 2022-23 they exported relatively limited waste for landfill (6,653 tonnes and 6,803 tonnes respectively), all to Great Britain.

14. Waste is exported for various reasons. It can cost less than processing waste locally, it can assist councils in meeting their recycling targets, and it can reduce reliance on domestic landfill. There are benefits in exporting waste to countries where demand for it is high, as they have the necessary facilities and capacity for recycling and energy recovery.

15. However, Northern Ireland also often exports waste to other countries for recycling and energy recovery due to insufficient available local infrastructure to process it. Waste destined for international recycling or energy recovery should follow the requirements of the 1013/2006 Waste Shipment Regulations. As local targets to reduce landfill are increased, sufficient solutions must be in place to process waste in the most economic and environmentally friendly manner. Furthermore, exporting waste to countries which process and financially benefit from the waste, represents a potential loss of revenue for Northern Ireland.

16. Waste exported for recycling and energy recovery is included in the figures used by councils to meet their targets, meaning there are risks that Northern Ireland could become too heavily reliant on other countries to meet future recycling and landfill targets. Should any future restrictions be introduced on exporting waste or if costs were to increase prohibitively, Northern Ireland would have to find alternative options for both dealing with the additional waste and meeting legislative targets.

Recommendation 4

We recommend that DAERA examines alternative options from exporting waste to ensure that Northern Ireland has contingency plans in place for dealing with this waste in the future, other than by landfill.

NIEA does not have a statutory requirement to track the capacities of Northern Ireland landfill sites, and this presents challenges for accurately forecasting adequate levels of supply.

17. All legal landfill sites in Northern Ireland are regulated by NIEA via the provision of an authorisation. Each site has a limited capacity. The total waste sent to landfill in 2022-23 was 1.29 million tonnes. The Circular Economy Package includes a municipal waste cap on landfill of 10 per cent per annum by 2035. Until successful waste prevention measures are in place, meeting the required reductions in landfill usage will be challenging. It is also necessary to ensure adequate landfill capacity is available to accommodate the required landfill waste disposal levels within waste management targets. NIEA is unsighted on current and future landfill capacity. A 2017 report by WDR & RT Taggart, estimates that landfill capacity in Northern Ireland will run out in 2028.

Recommendation 5

We recommend that projected landfill capacities are determined by NIEA to facilitate future planning and inform waste management policy and strategy.

Incomplete data for specific types of waste, such as Commercial and Industrial (C&I) waste and Construction, Demolition and Excavation (CDE) waste, present challenges for effective environmental and economic forecasting.

18. Household waste accounts for approximately 86 to 90 per cent of total waste collected by councils. The remaining per cent is made up of C&I waste. Local Authority Collected Municipal Waste (LACMW) or council collected waste data is collated by NISRA and DAERA, who report key outcomes quarterly and annually. However, there is insufficiently robust data for C&I waste not collected by councils and all CDE waste, which represents approximately 65 per cent of total waste in Northern Ireland. This presents DAERA and NIEA with significant challenges in assessing performance against C&I and CDE waste targets.

19. These information gaps are a UK-wide problem. The UK government (through Defra) is in the process of introducing a mandatory centralised digital waste tracking system to support the regulation of waste, which will track the amount, type, and ultimate destination of waste. DAERA, along with the relevant departments from the devolved nations, was consulted on system requirements. Defra has a budget of £9.5 million for the system and anticipates that it will be operational by April 2025. In a June 2023 report the National Audit Office noted that the introduction of the system faces similar challenges to other digital projects generally within the public sector, including skills gaps, insufficient planning, and potential to go over budget and timescales.

20. The tracking system’s objective is to both improve data and to deter criminality in the waste sector.

Recommendation 6

We recommend that throughout this wider process of making improvements to waste data, DAERA engages with Defra to ensure that Northern Ireland waste management requirements are met.

The cost of managing waste is considerable. All bodies involved should consider what options are available to promote collaborative working, improve cost effectiveness and standardise service delivery.

21. We understand Councils are actively considering how best to deliver more cost effective and consistent waste management services. In our view the establishment of a single delivery body for waste management services is one option that could be explored. A single delivery body holds the potential for significant benefits. It could streamline operations, promoting efficiency and cost effectiveness. A single approach could foster greater coordination across the region, offering consistency that would improve service quality and delivery. A centralised approach to waste management might also benefit more widely allowing for innovative solutions that might be economically feasible to pursue and achieve targets.

Recommendation 7

We recommend that DAERA work with the Councils and other stakeholders to ensure that the consideration of waste management solutions align to the Waste Management Strategy.

There are a significant number of waste management groups, with various roles and responsibilities, which will add a level of complexity, when attempting to implement the Waste Management Strategy.

22. It is important that all groups are working collaboratively to promote efficient and effective delivery of waste management. By its nature waste management is complex, so it becomes even more imperative that it is clear to all stakeholders the roles and the responsibilities of each body or group, the frequency of their meetings, and that there is access to the meeting minutes. When the roles and responsibilities are clear, performance can be more effectively monitored, and areas of improvement highlighted more readily. Simplified structures, setting out key roles, responsibilities, and deliverables, with clear lines of reporting and involving key stakeholders could enhance the quality and timeliness of decision making and oversight.

Recommendation 8

There are a significant number of waste management groups, with various roles and responsibilities. These organisations should work collaboratively, to avoid adding a level of complexity, when attempting to implement the Waste Management Strategy.

Part One: Why waste management matters? - Background

1.1 Waste management is a critical aspect of modern society, and its effective implementation is essential for environmental sustainability and public health. Waste management involves the collection, treatment, disposal, and recycling of various waste generated by both residential and industrial activities. Optimising waste management practices is crucial to making more efficient use of resources, minimising the negative impact on the environment, and creating a more sustainable future.

1.2 The 2008 European Waste Framework Directive provided an overarching framework for all member states in relation to waste management, essentially setting out what waste is and how it should be managed. The Waste Framework Directive defined waste management as:

‘The collection, transport, recovery and disposal of waste, including the supervision of such operations and the aftercare of disposal sites and including actions taken as a dealer or broker.’

The Waste Framework Directive represented an initial move towards a circular economy where products and materials are recovered and regenerated rather than disposed of. It identified the Waste Hierarchy (Figure 1) as representing best practice in waste legislation and policy.

Figure 1. Waste Hierarchy

SOURCE: Directive 2008/98/EC on waste (Waste Management Plan for Northern Ireland 2019)

1.3 The waste management hierarchy is a concept that outlines the preferred order of waste management practices, with the most desirable option at the top:

1. Waste Prevention: the best approach is to avoid generating waste in the first place through addressing product design, packaging reduction, and lifestyle changes that minimise waste production.

2. Reuse: if waste cannot be prevented the next step is to find ways to reuse items or materials to extend their lifespan, including through repairing, refurbishing, or donating items for further use.

3. Recycling: recycling involves processing waste materials to create new products. It helps conserve resources and reduces the need for extracting raw materials, lessening the environmental impact.

4. Recovery: When recycling is not feasible or efficient, certain waste materials can be converted into energy through processes such as waste to energy incineration or anaerobic digestion.

5. Disposal: Landfilling or incineration without energy recovery should be the last resort for waste that cannot be prevented, reused, recycled, or recovered. Proper disposal practices are essential to minimise environmental harm and potential risks to human health.

Part Two: Overview of Waste Management Framework in Northern Ireland - Background

2.1 Estimates indicate that Northern Ireland generates around 7.7 million tonnes of waste annually. The total volume of waste generated can only be estimated because robust data is not currently gathered for the majority of waste generated in Northern Ireland. Waste is categorised based on its source and its composition and includes those below.

Construction, Demolition and Excavation (CDE) Waste is waste from any building works, demolition, and development, including road planning and maintenance. This waste covers materials such as concrete, bricks, wood, glass, metals and plastics. NIEA estimates that around 5 million tonnes of CDE waste is generated annually, representing 65 per cent of the total for NI.

Commercial and Industrial (C&I) Waste refers to waste created from commercial activity or generated by manufacturing or various industrial processes. An estimated 1.1 million tonnes of C&I waste is generated annually (14 per cent of the total). C&I waste includes some non-household waste collected and processed by local councils.

Household Waste is primarily collected and processed by local councils. Approximately 0.8 million tonnes of household waste is generated annually (10.5 per cent of total waste generated).

Other Waste represents waste from forestry, fishing, agriculture and mining and various other waste sources. An estimated 0.8 million tonnes is generated each year (around 10.5 per cent of the total waste).

2.2 Figure 2 sets out the estimated quantities of waste across the four categories to try to understand the overall picture in Northern Ireland. The only robust data available is for the household figure of 0.8 million tonnes; the remaining figures are estimates drawn from various reports and from the NIEA. It should be noted that some of this data is now fifteen years old and may not be representative of the picture today.

Figure 2: Waste Estimates for Northern Ireland

Source: estimates obtained from various sources such as WRAP Study ‘Northern Ireland Commercial and Industrial (C&I) Waste Estimates 2009’, Waste Management Plan for Northern Ireland 2019, (CDE estimates) and NIEA Control and Data Management.

2.3 Local Authority Collected Municipal Waste (LACMW) is the household and C&I waste collected by local councils. Detailed and robust data is gathered and reported on the quantities collected, processed and the manner of disposal (recycled, used for energy recovery, or sent to landfill.) This is published quarterly and annually and is publicly assessable via the DAERA website. Northern Ireland local authority collected municipal waste management statistics | Department of Agriculture, Environment and Rural Affairs (daera-ni.gov.uk)

2.4 Since 2006-07, the LACMW data indicates that household waste accounted for between 86 and 90 per cent of total waste collected by councils; the remainder is C&I waste. Local councils collect around one million tonnes of waste annually.

2.5 The eleven local councils spent approximately £170 million in 2021-22 on the collection, processing and disposal of waste.

2.6 The type of data collected for LACMW is not collected for the various other categories of waste such as C&I and CDE. This is due to limitations in the availability and accuracy of this type of data across the whole of the UK. This presents challenges for DAERA in setting targets around prevention, processing and measuring progress against those targets. It also means that DAERA is poorly sighted on how around 80 per cent of waste is managed in Northern Ireland. This limits its ability to forecast trends in waste generation, processing, and disposal in Northern Ireland.

Legislation

2.7 DAERA is responsible for making legislation and implementing waste management policy. The Northern Ireland Environment Agency (NIEA), an Executive Agency within DAERA, regulates waste facilities and activities. The local councils have operational responsibility for the collection and processing of municipal waste which includes both household waste and some C&I waste.

2.8 The Waste and Contaminated Land (Northern Ireland) Order 1997 provides the basis for DAERA and the NIEA’s legislative responsibility for regulation of the waste management system. The EU Directive 2008-09 (the Waste Framework Directive) was implemented for Northern Ireland by the Waste Regulations (Northern Ireland) 2011 using power in the Waste and Contaminated Land Order and Section 2(2) of the now repealed European Communities Act 2972. The 2011 Regulations also updated the Waste and Contaminated Land Order to reflect additional obligations of the Waste Framework Directive. The Order, either initially or following amendments over the years, has provided the powers to introduce measures intended to increase control of the processing and handling of waste, including Waste Management Licensing, Duty of Care, Registration of Carriers, Special Waste and Producer Responsibility. The Waste Management Licensing Regulations (Northern Ireland) 2003 set out the framework for Waste Management Exemptions.

2.9 The Controlled Waste and Duty of Care Regulations (Northern Ireland) 2013 replaced the Controlled Waste Regulations 2002. They clarify how waste is classified and identify the types of household waste for which collection charges may be made. Under these regulations, waste holders and transporters have a duty of care to carry, produce and retain waste transfer notes; the regulations set out what information should be included on waste transfer notes.

Local Councils

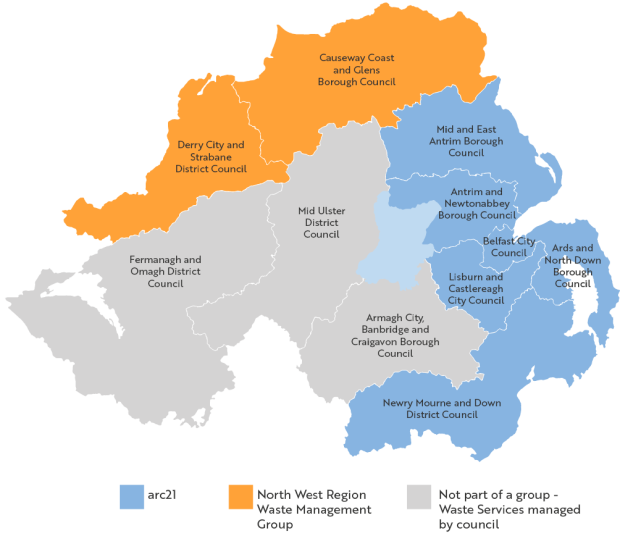

2.10 Eight of the eleven councils are represented by two Waste Management Groups, with three councils managing their waste responsibilities independently (Figure 3). The Waste Management Groups support the affiliated councils in developing and delivering waste management infrastructure and strategies.

Figure 3: Waste Management Groups for Local Councils

2.11 Established in 2003, arc21 represents six councils and is a contracting authority which procures services, infrastructure and auxiliary supplies for its affiliated councils. Its decision-making forum comprises 18 elected members, three from each council. The North West Region Waste Management Group is a voluntary coalition of two councils that aims to provide community and civic leadership in providing improved waste management services.

2.12 A single delivery model for all councils is one option that could be further considered in the context of waste management. Thorough cost, benefit, and risk analysis and in-depth consultation with the councils would be required before it could be determined if a single delivery model representing the eleven councils would be preferable to the current way of working.

Waste Representative Bodies

2.13 In addition to the main statutory stakeholders, a significant number of groups, boards, forums and partnerships also have roles in the oversight and implementation of the Northern Ireland Waste Management Strategy:

Government Waste Working Group – Responsible for reviewing the implementation of the Waste Management Strategy and reporting to the Minister. Membership includes representation from DAERA, NIEA, councils, SIB, and Northern Ireland Waste Management Groups.

DAERA Waste Strategy Executive Board (DWSEB) – a DAERA group, responsible for monitoring and reviewing the Waste Management Strategy. This Board allows DAERA to consider the performance of the Waste Management Strategy against strategic and political drivers, objectives, and outcomes.

The Council Waste Forum (CWF) – A collaboration group with representation from all 11 councils to strategically review waste governance arrangements for Northern Ireland councils. It was established in 2018 and its principal function is “to promote and deliver collaboration between the eleven councils on all matters relating to Waste Management and Environmental Cleansing.”

Strategic Waste Partnership Board (SWPB) – Responsible for providing oversight of action plans for central and local government and managing municipal waste. Membership includes DAERA, council, and SIB.

Waste Co-ordination Group (WCG) – A non-executive advisory group providing a forum to discuss the operational and policy issues relevant to the statutory responsibilities of public sector waste.

2.14 We consider that all stakeholders would benefit from clearer articulation of the roles and responsibilities of these various groups. A more simplified structure, setting out key roles, responsibilities and deliverables, with clear lines of reporting and involving key stakeholders, could enhance the quality and timeliness of decision-making and improve oversight. This could coincide with the development and publication of the new Waste Management Strategy.

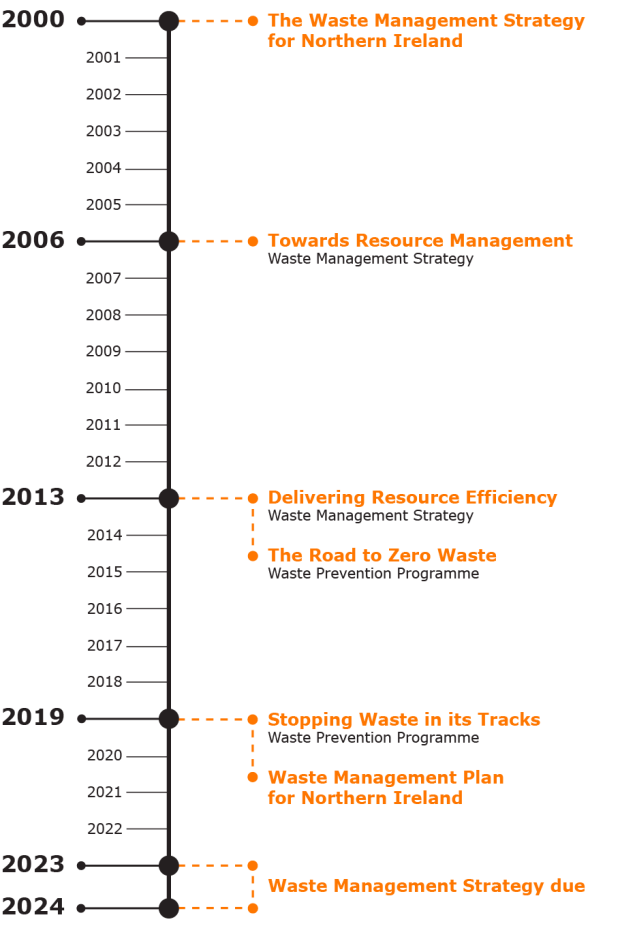

Figure 4: Timeline of Waste Management Strategies

Waste Management Strategies

2.15 As Figure 4 shows, three Waste Management Strategies have been published in Northern Ireland to date; ‘The Waste Management Strategy for Northern Ireland’ was published in 2000, ‘Towards Resource Management’ was published in March 2006 and ‘Delivering Resource Efficiency’ was published in 2013.

2.16 ‘Towards Resource Management’ (2006) focused on waste and resource management, rather than emphasising prevention, preparing for reuse, and recycling.

2.17 The Waste Management Strategy, ‘Delivering Resource Efficiency’ (2013) set out the policy framework until 2020. It was built on the core principles of the 2006 Strategy but placed renewed emphasis on the Waste Hierarchy (Figure 1) and on waste prevention.

2.18 DAERA published the closure report of the 2013 Strategy, ‘Delivering Resource Efficiency’ in June 2022. The report details the outcome of the 27 waste-related actions and 17 targets. More detail is provided in Part Four.

2.19 The closure report represents the starting point for DAERA’s work to develop a new Waste Management Strategy. As part of that process, DAERA held stakeholder events on 29 September and 13 December 2022 and was due to publish the Waste Management Strategy towards the end of 2023. Due to resourcing, DAERA had to stop work on the new strategy and the publication has been delayed until 2024, with an exact date to be confirmed by the Department.

Waste Management Plan for Northern Ireland (WMPNI) 2019

2.20 Published in 2019, the Waste Management Plan for Northern Ireland (WMPNI) fulfilled an EU Directive requirement for member states to establish one or more waste management plans. This Directive requires member states to evaluate their waste management plans and waste prevention programmes every six years.

2.21 The WMPNI is a higher level document than the Waste Management Strategies. It analyses the current waste management situation and evaluates how the objectives and provisions of the EU Directive will be implemented. The plan’s key aim is to set Northern Ireland’s intentions to work towards a sustainable and circular economy, with particular focus on using the waste hierarchy to achieve sustainable waste management. However, the plan is a limited document in nature, as it mainly reflects proposals from the most recent Waste Management Strategy and other Waste Management Plans (including those compiled by arc 21 and the North West Region Waste Management Group) and does not introduce new polices or proposals for changing how waste is managed in Northern Ireland.

2.22 The WMPNI includes a chapter on the Current Waste Management Situation in Northern Ireland and a chapter on Waste Arisings. It recognises that action is required by householders, local councils, businesses, and consumers. However, as it does not propose any new plans or measures to further improve local waste management or make it more sustainable, it is important that the updated Waste Management Strategy, which is under development, is published as soon as possible.

Waste Prevention Programmes for Northern Ireland

2.23 The Waste Framework Directive requirement to produce a Waste Prevention programme was transposed into the Waste Regulations (Northern Ireland) 2011. The Department of the Environment published Northern Ireland’s first Waste Prevention programme in 2013, ‘The Road to Zero Waste’. This programme proposed 13 waste prevention actions.

2.24 DAERA published a second Waste Prevention programme in 2019, ‘Stopping Waste in its Tracks’. This programme aimed to build on ‘The Road to Zero Waste’ and maintain the emphasis on “the downward trend in waste arisings by decoupling economic growth from the environmental impacts associated with waste generation.”

2.25 The 2019 programme includes twenty-two actions for DAERA. Unlike the actions detailed in the 2019 Waste Management Plan, the waste prevention programme actions do not include a means to measure performance, such as a date by which they are to be achieved.

Key Points

The previous Waste Management Strategy expired in 2020. Strategic direction is required over the future of waste management in Northern Ireland. It is important that the new strategy robustly addresses how further improvements can be achieved for waste prevention, increasing reuse, recycling and recovery, and continuing to reduce reliance on landfill.

Part Three: Performance and Achievements within Waste Management

3.1 The 2013 Waste Management Strategy contained 17 targets and 27 actions across seven themes (total of 44 targets and actions):

- Waste Prevention – 1 target and 2 actions

- Preparing for Re-use – no specific targets or actions

- Recycling – 14 targets and 9 actions

- Other Recovery – 7 actions

- Disposal – 2 targets and 4 actions

- Better Regulation and Enforcement – 4 actions

- Communication and Education – 1 action

3.2 The June 2022 closure Report for the 2013 strategy, Closure Report Northern Ireland Waste Management Strategy 2013 | Department of Agriculture, Environment and Rural Affairs (daera-ni.gov.uk), recorded that: 22 (50 per cent), of the actions and targets were achieved; 10 (23 per cent) were achieved beyond the target date; 4 (9 per cent) were superseded, or alternative action taken; 3 (7 per cent) were partially achieved; and 4 (9 per cent) were not achieved but improvements were made. Only one action was recorded as not achieved.

3.3 In relation to recycling targets, the recycling rate of 60 per cent of locally collected municipal waste was not achieved, but improvements were made, with the 50 per cent target for household waste being met. Locally collected municipal waste is a mix of household and Commercial and Industrial (C&I) waste, household waste is waste collected by councils from domestic properties.

3.4 Some of the actions recorded as achieved beyond the target date include DAERA issuing comprehensive guidance on separate collections by April 2014. It is recorded that the EU guidance was sufficient and issued to councils in November 2015.

3.5 The one action recorded as not achieved was to reach an overall energy recovery rate of 79 per cent and overall recycling rate of 72.7 per cent of packaging by 2017. Energy recovery is the process of converting waste into energy, such as incineration. (In 2017, the UK recycling rate for packaging waste was 63.9 per cent and the EU rate was 67.5 per cent.)

3.6 For some of the actions and outcomes, additional information is limited, in particular for those marked as ‘not achieved but improvements made’. The closure report acknowledges that having multiple targets within one action or target makes monitoring the performance more difficult. It suggests that in the next Waste Management Strategy, actions and targets should be separated to facilitate assessment.

3.7 Details of all the actions and their outcomes are set out in Appendix 1.

Council Performance against Waste Targets

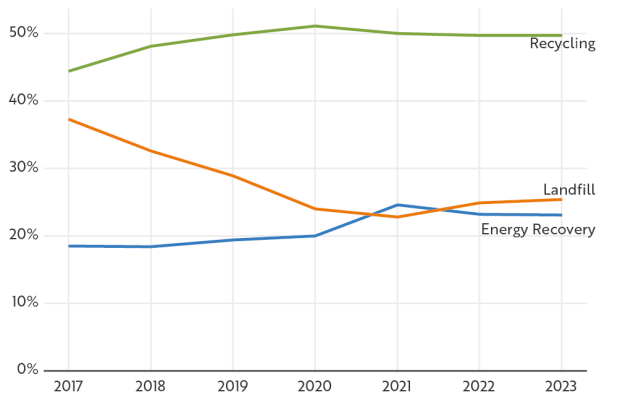

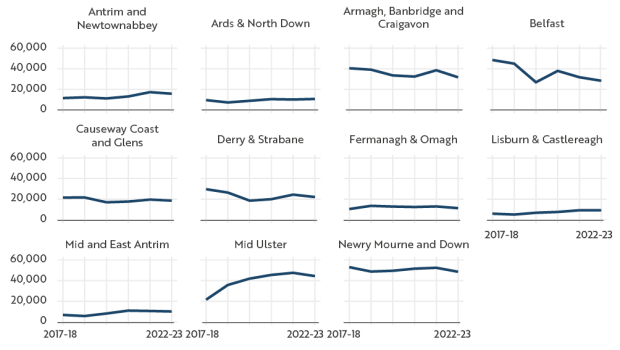

3.8 The eleven local councils in Northern Ireland collect and process approximately one million tonnes of Local Authority Collected Municipal Waste (LACMW) annually. Figure 5 shows the percentage rates of this waste that is recycled, used for energy recovery, and sent to landfill between 2016 and 2023.

Figure 5: Percentage Rates of LAC Municipal Waste in Northern Ireland 2017-23

Source: Northern Ireland Local Authority Collected Municipal Waste Management Statistics

3.9 Councils are required to report on local authority collected waste on a quarterly basis via the Waste Data Flow system. This system was developed in 2004 to replace various waste questionnaires that had to be completed by local authorities, with a single data set. The data is publicly accessible and enables government to track progress against targets, WasteDataFlow Waste Management.

3.10 The LAC Municipal Waste Data, as collected by NISRA and DAERA, shows local councils collected 0.97 million tonnes of municipal waste in 2022-23, with 49.7 per cent of this sent for recycling. In that year, council collected waste sent to landfill amounted to 23.1 per cent and 25.4 per cent was sent for energy recovery. Energy recovery figures as reported are derived from waste sent for recovery via incineration and gasification. Just over 120,000 tonnes of biodegradable waste was sent to landfill during 2022-23, a decline from 140,000 tonnes in 2021-22.

3.11 Household waste accounted for 87.1 per cent of all waste collected by councils. For this type of waste only, the recycling rate was 50.7 per cent, and the landfill rate was 22.4 per cent. The LAC Municipal Waste Data does not record data for energy recovery specifically for household waste; the figure given accounts for the amount of waste sent for energy recovery from all sources.

3.12 The total quantity of local authority collected (LAC) municipal waste arisings is a key performance indicator which is also used to monitor performance under the Local Government (Performance Indicators and Standards) Order (Northern Ireland) 2015. It enables stakeholders to track annual increases in the volume of municipal waste, to assess key metrics around recycling, energy recovery and ongoing reliance on landfill, and to inform future waste management planning.

3.13 Total waste arisings fell from 1.06 million tonnes in 2006-07 to a low of 910,000 in 2012-13, a 14.1 per cent decrease. Since then, total arisings showed a generally increasing trend, until 2022-23 when waste arisings decreased by 6.1 per cent to 970,000 tonnes.

Council Performance against Recycling Targets for Municipal Waste

3.14 Northern Ireland’s target was to prepare for reuse or recycle 50 per cent of household waste by 2020. This target was met by councils, but only narrowly, with a recycling rate of 51.9 per cent in 2019-20, 50.9 per cent in 2020-21, 50.1 per cent in 2021-22 and 50.7 per cent in 2022-23.

3.15 Achieving the required recycling rate of 50 per cent for household waste by 2020 represents important progress by local councils. Challenges lie ahead for the councils as they aim to achieve the further increases that will be necessary to meet the new requirements that have been set, including a rate of 55 per cent of municipal recycling by 2025 and a requirement to achieve at least 70 per cent by 2030.

Council Performance against Landfill Targets for Municipal Waste

3.16 The Northern Ireland Landfill Allowance Scheme (NILAS) was introduced in 2005 and translated the Landfill Directive Targets into annual allowances for each council. The most recent statutory landfill targets for councils was an overall annual limit of 220,000 tonnes of biodegradable local authority collected municipal waste by 2020.

3.17 The 2013 Waste Management Strategy set landfill targets of no more than 429,000 tonnes of biodegradable municipal waste (BMW) and 220,000 tonnes of biodegradable locally collected municipal waste. These targets were recorded as achieved in the Waste Management Strategy’s closure report. Figure 5 shows how the percentage of council collected waste sent to landfill has reduced very significantly across the three main categories since 2006-07.

3.18 In 2022-23, a total of 225,000 tonnes of waste was sent by councils to landfill, representing a 12.8 per cent decrease from 257,900 tonnes in 2021-22. The landfill rate for 2022-23 was 23.1 per cent.

3.19 The landfill rate for household waste fell to its lowest value in 2020-21 at 22.4 per cent. It then increased slightly to 24.7 per cent in 2021-22 but has fallen again to 22.4 per cent in 2022-23. These general trends of a reduced reliance on landfill are positive.

3.20 The Food Waste Regulations (Northern Ireland) 2015 provided for the separate collection of food waste and required councils to provide households with food waste containers which will have contributed to the falling landfill rates. The Landfill Tax for household waste is a key incentive for councils to reduce landfill. This is charged on waste disposed at landfill sites and is paid to HMRC. Currently, a lower tax (£3.25 per tonne) applies to less polluting materials and a standard rate (£102.10 per tonne) is levied on all other material disposed of at authorised sites.

3.21 The achievements to date in meeting previous targets is a solid basis on which to move forward but the introduction of new targets, including further reductions in landfill rates, will be challenging. Together with other stakeholders, the councils will need to set out a strategic plan for meeting these.

3.22 Importantly, there is also a lack of clarity over how much landfill capacity remains in Northern Ireland. A 2017 report by WDR &RT Taggart, (commissioned by the Tullyvar Joint Committee (Mid Ulster District Council with Fermanagh & Omagh District Council) as part of the decision-making process regarding the future of the Tullyvar Landfill Site which remains ‘mothballed’) predicted that Northern Ireland would run out of landfill by 2028. NIEA does not have a statutory obligation to collate the landfill capacities for authorised operational landfill sites. At a time when the volume of waste generated is increasing, this presents challenges in accurately forecasting whether adequate future landfill capacity will be available to support waste management needs in Northern Ireland, and in assessing future planning for infrastructure required to support greater recycling and energy recovery. It also emphasises the importance of more robust strategies for waste prevention. We consider that landfill capacity within Northern Ireland needs to be formally and regularly estimated to inform future planning and target setting for landfill rates for local authority collected municipal waste.

Council Energy Recovery Rates for Municipal Waste

3.23 Energy Recovery is a form of resource recovery in which the organic fraction of waste is converted into some form of usable energy. This can be achieved by incineration, gasification, pyrolysis (a process of thermal decomposition of materials at elevated temperatures, it can be used to convert biomass into bio-oil, biochar and syngas), valorisation and anaerobic digestion.

3.24 Most energy recovery comes from mixed residual waste, which is collected from kerbsides and from civic amenity sites by councils and processed into refuse derived fuel. Some also comes from specific types of waste, mainly wood, and includes items collected from civic amenity sites such as furniture, carpets, and mattresses. Figure 5 shows how the percentage of waste collected by councils and sent for energy recovery has increased notably between 2006-07 and 2022-23.

3.25 Figure 5 does not include energy recovery from anaerobic digestion as DAERA and NISRA account for these tonnages separately. This is because most council collected waste undergoing anaerobic digestion in Northern Ireland ends up as compost.

3.26 Before 2009-10, virtually no waste was sent for energy recovery in Northern Ireland but by 2020-21, the energy recovery rate had increased to 24.6 per cent. In 2022-23, almost 250,000 tonnes of waste was sent by councils for energy recovery which produced an energy recovery rate of 25.4 per cent. This was higher than the 2021-22 rate of 23.2 per cent, with just over 240,000 tonnes sent by councils for energy recovery. Whilst energy recovery is a carbon intensive process, for the majority of waste streams, it is still environmentally preferable to use this method instead of landfill, for waste that cannot be reused or recycled, in accordance with the waste hierarchy. It is important that Northern Ireland has suitable infrastructure and waste management practices in place to ensure that only waste that cannot be reused or recycled is sent for energy recovery.

Export of Waste

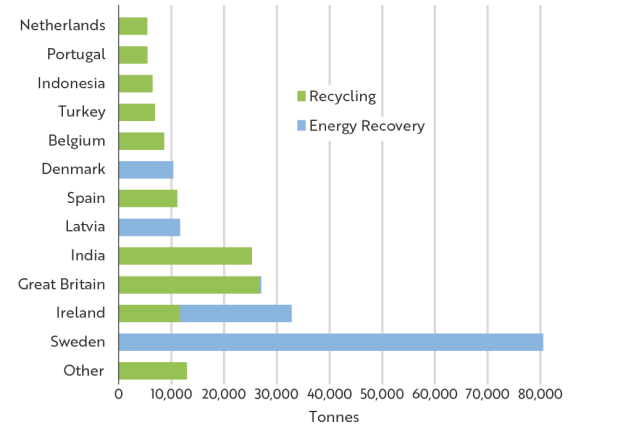

3.27 Waste is exported for various reasons. It can cost less to export than to process locally, it can assist the exporting country meet their recycling targets, and it can reduce reliance on domestic landfill. Exporting waste can also be economically advantageous to countries which have a high demand for it and have the necessary recycling or energy recovery facilities and capacity. As stated in 3.26 above, energy recovery is environmentally preferable to landfill.

3.28 As Figure 6 shows, the total waste exported by the 11 local councils increased by 6 per cent, from 259,000 tonnes to 275,000 tonnes, between 2017-18 and 2021-22. In 2022-23, the total waste exported decreased to 250,000. During this period, reported levels increased at six of the councils but reduced at the other five. In 2022-23, the volume of waste exported varied from 9,300 tonnes (Lisburn and Castlereagh) to 48,000 tonnes (Newry, Mourne and Down). This illustrates the variable reliance of individual councils on exporting to achieve their waste management targets. Positively, councils export waste primarily for recycling and for energy recovery. In 2022-23, they only collectively exported 6,800 tonnes of waste for landfill, all to Great Britain.

Figure 6: Total Amount of Waste Exported by Councils 2017-2023

3.29 In 2022-23, the 11 councils exported just over 123,000 tonnes of waste for energy recovery to six countries, including over 80,000 tonnes exported to Sweden and 20,000 tonnes to Ireland. In that year, almost 121,000 tonnes was also exported for recycling to twenty-two countries. This included 26,800 tonnes exported to Great Britain, and 25,300 tonnes exported to India (Figure 7).

3.30 As well as lower costs, Northern Ireland exports waste to other countries for recycling and energy recovery due to insufficient local infrastructure to process it. There are economic and environmental costs associated with shipping waste around the world, but it is difficult to quantify the extent of this for council waste exported from Northern Ireland. Waste exported from Northern Ireland for recycling and energy recovery follows the requirement of the 1013/2006 Waste Shipment regulations, and there is a low rate of waste repatriation for exports of waste. As targets to further reduce landfill are set, stakeholders will need to plan to ensure that sufficient local infrastructure is in place to process waste in an economic and environmentally friendly manner, or reliance on exporting will likely continue to increase.

3.31 The Department has advised that there is also a significant amount of waste imported from England, Scotland, and Wales to Northern Ireland for processing, which can put pressure on the Northern Irish waste infrastructure.

3.32 Waste that has been exported for recycling and energy recovery is included in the figures used by councils to meet their targets. There are risks attached to Northern Ireland’s reliance on other countries to meet future recycling and landfill targets. Should there be any restrictions in the future on the exporting of waste or introduction of prohibitively high costs, Northern Ireland would have to find alternative options for dealing with waste to meet targets.

3.33 In addition to local councils, businesses in Northern Ireland also export waste. International waste exports and imports are referred to as ‘Waste Shipments’. The process for exporting and importing waste is referred to as the Transfrontier Shipment of Waste (TFS). Waste shipments are subject to TFS regulatory controls that depend on whether the waste is being sent for recovery or disposal, the type of the waste, the status of the dispatch and the destination of countries. Written permission from NIEA is required before specific waste shipments can be moved to or from Northern Ireland. These shipments are referred to as notifiable waste shipments. The notification fees paid to NIEA for notifiable waste exported in 2023 were £78,000, the notification fees for imported and exported waste were £504,000.

3.34 In 2023 NIEA recorded that 998,000 tonnes of TFS waste was exported, including notifiable waste and green list waste. The transport of green list waste does not require written permission from NIEA but those responsible for transporting must comply with TFS requirements.

Figure 7: Destination of Waste Exported by Councils for Recycling and Energy Recovery 2022-23

3.35 Council collected waste only represents approximately 13 per cent of the total waste generated in Northern Ireland. Total waste figures for Northern Ireland can only be estimated due to the challenges around the availability of many types of waste data. Performance against targets for the local authority collected municipal waste can be measured, as robust and validated data is gathered by DAERA and NISRA. However, the ability to forecast, assess performance and manage waste for the other approximately 87 per cent of waste is more difficult, due to the lack of data.

3.36 The 2019 Waste Management Plan for Northern Ireland estimated that Northern Ireland recycled or recovered 79.4 per cent of non-hazardous CDE waste, which accounts for around 65 per cent of waste arisings in Northern Ireland. This exceeds the C&D recycling or recovery target of 70 per cent by 2020, as set by the 2013 Waste Management Strategy, but it is based on estimates, as more robust data is required to confirm outcomes.

3.37 Stakeholders have long recognised the difficulties around collecting data for specific waste streams. This problem is not specific to Northern Ireland. The UK government is currently in the process of introducing a mandatory UK-wide digital waste tracking system. This aims to support effective regulation of waste (including addressing waste crime), to track how waste produced in the UK is being managed and disposed of and to move towards a more circular economy. As a partner in the project, DAERA is involved in its development. DAERA is working with Defra towards a launch date of April 2025 for waste tracking in Northern Ireland. The timely introduction of this system would help address longstanding and important information gaps.

Waste to Landfill in Northern Ireland in the Last Five Years

3.38 In 2022-23, 225,000 tonnes of council collected municipal waste was sent to landfill. In 2022-23, a total of 1.9 million tonnes of all types of waste was disposed of through landfill.

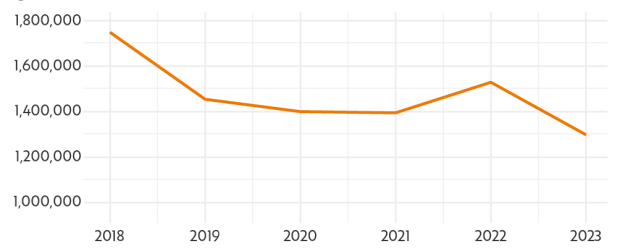

3.39 Waste is classified by the European Waste Catalogue (EWC) Codes. The EWC Codes comprise chapters describing waste arising from different types of activity, and bodies involved in transporting or disposing of waste are legally required to classify it using these chapters. As Figure 8 shows, the total volume of waste sent to landfill in Northern Ireland reduced from 1.74 million tonnes in 2017-18 to 1.39 million tonnes in 2021-22. However, this then increased to 1.52 million tonnes in 2021-22, before falling to 1.29 million tonnes in 2022-23. In the last five years, the type of waste which accounts for the most tonnes sent to landfill in Northern Ireland is ‘Construction and Demolition Waste’.

Figure 8: Tonnes to Landfill in Northern Ireland 2017 to 2023

Figure 9: Top Five Types of Waste (by EWC Chapter) sent to Landfill in Northern Ireland to nearest Tonne

| Type of Waste (EWC Chapter) | 2017-18 | 2018-19 | 2019-20 | 2020-21 | 2021-22 | 2022-23 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Construction and Demolition Wastes (including excavated soil from contaminated sites) | 1,060,480 | 795,760 | 774,470 | 818,350 | 907,000 | 800,480 |

| Waste from Waste Management Facilities, Off-Site Wastewater Treatment Plants and the Preparation of Waste for Human Consumption and Water for Industrial Use | 309,270 | 311,280 | 366,910 | 343,380 | 368,890 | 275,540 |

| Municipal Wastes (Household Waste and Similar Commercial, Industrial and Institutional Wastes, including Separately Collected Fractions) | 328,420 | 296,890 | 256,240 | 211,030 | 206,270 | 200,520 |

| Waste From Thermal Processes | 34,720 | 38,800 | 21,900 | 11,690 | 35,570 | 11,480 |

| Other | 8,520 | 7,000 | 6,470 | 6,320 | 6,070 | 6,940 |

| Total | 1,741,410 | 1,449,730 | 1,425,990 | 1,390,770 | 1,523,800 | 1,294,960 |

3.40 The volume of waste sent to landfill must be considered in the context of the total amount of waste generated in Northern Ireland. Rates of prevention, reuse and recycling must increase to ensure that reliance on landfill does not start rising again in the longer term. This once again indicates the importance of effective planning by stakeholders around ensuring how best practice, advocated by the Waste Hierarchy, can be implemented through enhancing both waste prevention activities and the levels of waste recycled or recovered.

3.41 As well as concerns around capacity, NIEA may potentially be exposed to costs associated with legal landfill sites if owners go out of business during or post operation of the site. Prior to NIEA issuing a permit for the operation of a landfill site, the operator and NIEA must agree on the financial and environmental liabilities associated with each stage of the landfill site, including post closure. This is known as Financial Provision, which is required to be assessed by NIEA at application stage but also on an annual review basis as required by the permit conditions. For landfill sites the current NIEA Financial Provision Policy allows for the following mechanisms to be accepted: escrows, bonds and renewable bonds, cash, and local authority deed agreements.

3.42 NIEA sought advice around ‘orphaned’ landfill sites from the Departmental Solicitor’s Office in the Department of Finance to understand where responsibility falls in such circumstances. The issue is complex and is to be addressed on a site-specific basis. The Department is working with other sister agencies to explore the best options to address the risk of abandoned landfill sites. To date there have been no incidents of ‘orphaned’ landfill sites in Northern Ireland, but it is a risk that must be managed by NIEA.

Waste Crime in Northern Ireland

3.43 Waste crime refers to illegal activities associated with waste management. It can include illegally dumping hazardous waste, misclassification of waste to avoid disposal fees and operating without waste authorisations. Waste crime can occur across many sectors, both public and private, with considerable environmental and economic impacts.

3.44 The environmental consequences of waste crime include the release of harmful substances which can contaminate ecosystems, pose risks to public health and compromise biodiversity in the long-term.

3.45 Waste crime imposes economic burdens, with government and local authorities incurring costs for clean-up and remediation operations. Legitimate waste management stakeholders can face unfair competition from illegal operators, creating economic distortions within the industry.

3.46 Effectively enforcing laws against waste crime is very challenging, in part due to the nature of illegal waste management and disposal and in part due to the limited resources available to tackle this type of criminality.

3.47 A recent example, which had considerable media coverage, is the illegal waste site on the Mobuoy Road in County Derry/Londonderry. The site is believed to be one of the biggest illegal waste sites in the UK or Ireland. The Mobuoy site highlights the complexity of addressing waste crime. The NIEA has carried out extensive site investigations and monitoring, completed and published a detailed quantitative risk assessment of the site. A Remediation Options Appraisal process has been completed and published. This work underpins and informs the remediation strategy for the site which has been developed in draft. The NIEA is preparing to consult on this strategy. In the meantime, a comprehensive ongoing Environmental Monitoring Programme is in place for the site.

3.48 The scope of this report does not include an analysis of waste crime and its impact in Northern Ireland. The NIAO intends to produce a report focusing specifically on waste crime.

Key Points

DAERA reported that a high proportion of actions and targets from the 2013 Waste Management Strategy were achieved to some degree.

There have been welcome and notable increases in the levels of municipal waste recycled and recovered, and a reduction in reliance in landfill over the last five years. Progress has also been made in increasing the volume of waste sent for energy recovery from zero, or small quantities, before 2009-10 to almost 250,000 tonnes in 2022-23.

Councils will face challenges in meeting future targets, including a rate of 55 per cent of municipal recycling by 2025 and 70 per cent by 2030.

A lack of clarity over remaining landfill capacity in Northern Ireland creates uncertainty and challenges for forward planning.

Councils export around 260,000 tonnes of waste annually and this can bring mutual benefits to Northern Ireland and other countries. However, if exporting restrictions were to be introduced or exporting costs increase prohibitively, the need for additional domestic processing capacity would arise.

Robust waste management data is only recorded for council collected waste in Northern Ireland. A mandatory UK-wide tracking system scheduled for introduction in 2025 will help address longstanding information gaps, if successfully implemented on time. An increased availability of data will improve detection of illegal waste activities and, in time, should assist government and local authorities to deter criminal waste management practices.

Part Four: Future Challenges for Waste Management

Figure 10: Future Targets for the Waste Sector in Northern Ireland

4.1 Northern Ireland still has waste management targets that it must continue to meet, and other challenges it must respond to (Figure 10). With the publication of DAERA’s new Waste Management Strategy, a key focus will be to outline how the current recycling targets, to recycle 65 per cent of municipal waste and the requirement to recycle at least 70 per cent of overall waste by 2030, can be achieved.

4.2 In terms of waste prevention, a ‘Single-use Plastic Reduction Action Plan for the Government Estate’ has been implemented. DAERA is also currently preparing a consultation on a Plan to Eliminate Plastic Pollution, delivering a Waste Prevention Programme and issuing targeted waste prevention grants. Waste prevention remains key in effective waste management, and it would be expected that the new Waste Management Strategy would have added focus on how to achieve waste prevention.

4.3 The Climate Change Act (Northern Ireland) 2022 requires that Northern Ireland publishes the carbon budgets for the first three budgetary periods by the end of December 2023, a date that was not possible to achieve in the absence of the Northern Ireland Executive. The Climate Change Act (Northern Ireland) 2022 requires that Northern Ireland must then publish a plan for each budgetary period setting out proposals and policies for meeting that carbon budget for that period.

4.4 The main function of the Action Plan is to deliver on the carbon budget, which provides a limit on the maximum total amount of greenhouse gas emissions which should not be exceeded for a defined budgetary period. The Action Plan will also set out how the waste sector specific targets are to be met.

Waste Data

4.5 As discussed, the lack of data for approximately 87 per cent of waste generated in Northern Ireland reflects a UK-wide issue. A report published in June 2020 by WRAP (a climate change Non-Government Organisation) highlighted that “there is an urgent need for improvements in data quality especially for NHM (non-household municipal) sectors in order to enable more accurate forecasting of performance and cost, as well as understanding the relative contributions needed from each sub-sector.”

4.6 As highlighted, the UK government is currently developing a mandatory digital waste tracking system intended to support the regulation of waste by providing a single system to track the amount, type, and ultimate destination of waste. To support implementation in Northern Ireland, Defra has allocated a budget of £9.5 million and anticipates that the system will be complete by April 2025. In a June 2023 report the NAO noted that the introduction of this system faces the same challenges as digital projects more generally within the public sector, namely skills gaps, insufficient planning, and a tendency to go over budget and timescales. These factors will need to be well managed if the system is to be delivered on time and within budget.

4.7 The tracking system’s aim is both to improve data and to deter criminality in the waste sector. If the former objective is achieved, DAERA, NIEA and local authorities will be better placed to improve their waste forecasting capacity and plan for future challenges.

Producer Responsibility Obligations

4.8 Producer Responsibility schemes require producers to take some responsibility for the environmental impacts of their products. Extended Producer Responsibility moves this even further from design to beyond the end of life of a product. The schemes can involve setting targets for recycling and waste reduction, and financial responsibility for producers. There are four established producer responsibility schemes, for packaging, batteries, waste electrical goods, and end of life vehicles. These are all being reviewed to consider extended producer responsibility; the first being advanced is packaging. The schemes are UK wide and aim to incentivise producers to act more responsibly for the environmental impact of their products.

4.9 The European Directive on Packaging and Packaging Waste introduced producer responsibility into the management of packing materials. The Producer Responsibility Obligations (Packing Waste) Regulations (Northern Ireland) 1999 and 2007, and the Packing (Essential Requirements) Regulations 2015 implemented the EU Packaging and Packaging Waste Directive.

4.10 The Packaging Waste (Data Reporting) Regulations (Northern Ireland) 2023 bring in new data reporting obligations on packaging producers. DAERA also held a public consultation on the draft Producer Responsibility Obligations (Packaging and Packaging Waste) Regulations 2024. The consultation was to gather stakeholder views on how the agreed UK policy approach has been reflected in the draft Regulations and to receive feedback on whether the Regulations create clear and operationally feasible obligations.

4.11 The NAO 2023 report on waste highlighted the challenges that the packaging reforms have faced. These included delays and a lack of clarity around implementation, lack of understanding as to the changes required and uncertainty around any potential benefits of the scheme. The challenges faced by Defra are similar in Northern Ireland.

4.12 The Deposit Return Scheme (DRS) in England, Wales and Northern Ireland will place a redeemable deposit on polyethylene terephthalate (PET) single use plastic and metal drinks containers up to three litres. The DRS will be industry led, with the companies that produce the containers funding the scheme by paying fees to the deposit management organisation to cover the costs of running the scheme. The consumers will then pay an upfront deposit at the point of purchase which can be redeemed by returning the container at a return point.

4.13 Defra is developing this scheme alongside DAERA and the Welsh Government. Scotland is developing a separate scheme and has set the deposit at 20p per drinks container. Defra advised that it intended to review Scotland’s implementation of its DRS ahead of launching their own, but Scotland’s scheme has been delayed until 2025, which is when Defra now intends to launch its scheme, a delay from 2024. There have been two consultations by Defra, DAERA and the Welsh Government on the scheme, one in 2019 and one in 2021. Defra advised that it has a “stretching target date” for commencement for DRS of 1 October 2027.

4.14 The NAO 2023 report notes that each stage has taken longer than expected and that the consultations on the schemes have reduced the scope of the original proposals. The report also refers to concerns among stakeholders as to whether the scheme represents value for money, in part because the containers can be recycled via council collections.

4.15 Lack of clarity and certainty is challenging for business, and it is for DAERA to ensure that it provides producers with all relevant information to facilitate implementation and operation of the regulations as soon as possible.

Landfill Capacity

4.16 The Circular Economy Package (CEP) includes a requirement to cap the proportion of municipal waste sent to landfill in Northern Ireland to 10 per cent by 2035. It is anticipated that the new Waste Management Strategy will contain detail as to how this target will be met.

4.17 The total waste sent to landfill decreased from around 1.4 million tonnes annually in 2018-19 to 1.29 million tonnes in 2022-23. How much available landfill capacity remains in Northern Ireland is a challenge for the waste sector.

4.18 UK national and EU Member States are seeking to move away from landfilling and focus on recycling and recovery and, ideally, preventing waste. In the meantime, however, waste must be treated or disposed of and, to ensure this, accurate forecasting and planning is required. If the target of 10 per cent of municipal waste to landfill by 2035 is to be met, a 2015 Strategic Investment Report highlights that “All Residual Waste will require treatment rather than being sent directly to landfill as is currently the case. This will require significant additional infrastructure to provide necessary treatment capacity.”

Net Zero

4.19 Under the Climate Change Act (Northern Ireland) 2022, Northern Ireland is required to reach net zero greenhouse gas emissions by 2050. Waste management plays a key part in the move towards net zero by focusing on waste prevention through reusing rather than disposing of materials thereby reducing emissions through less consumption, improved recycling and recovery processes, and less transporting of waste.

4.20 There are concerns that the net zero target for Northern Ireland is not attainable. The Climate Change Committee (CCC), an independent statutory body established under the Climate Change Act 2008, wrote in a 2023 report that the target goes “significantly beyond their advice on what would be a fair and achievable contribution from Northern Ireland to the achievement of UK-wide Net Zero emissions.” The CCC has also highlighted the lack of waste data in Northern Ireland, and its impact on assessing whether Northern Ireland is on course to meet its net zero obligations.

4.21 It is anticipated that there will be a renewed emphasis on waste prevention in the next Waste Management Strategy with new statutory targets in relation to recycling, reusing and disposal of waste. The Strategy should also assess whether Northern Ireland has sufficient infrastructure in place to manage waste in an economical and environmentally friendly manner, and in compliance with net zero commitments.

Waste Infrastructure

4.22 DAERA has concluded that there is a need for additional waste infrastructure in Northern Ireland to process the quantities of waste that may arise in future years. Depending on the scale of waste infrastructure being developed, it is the responsibility of the relevant planning authority to determine planning permissions for such applications.

4.23 The only energy recovery waste plant in Northern Ireland is private sector operated, in Belfast’s Harbour Estate. It can combust just under 160,000 tonnes of refuse derived fuel annually. Refuse derived fuel is created by processing different types of waste, including municipal, and is considered environmentally preferable to landfill. Kilroot has received planning permission to construct a Multi Fuel Combined Heat and Power (CHP) facility at the power station in Carrickfergus, to generate electricity through the diversion of 314,000 tonnes of non-recyclables away from landfill every year. Once constructed and operational this will significantly contribute to Northern Ireland’s waste infrastructure.

4.24 There are thirteen waste-fed anaerobic digestion facilities in Northern Ireland, according to the Official Biogas Map, last updated in April 2023, and 58 farm-fed facilities. Waste-fed anaerobic digestors use municipal, commercial, and industrial waste as feedstock. Most of the biogas generated is used for onsite combined heat and power, with surplus electricity sold to export suppliers.

4.25 The proposed £240 million energy from waste (EfW) plant and additional recycling facilities at Mallusk, County Antrim could process an anticipated 250,000 tonnes of black bin waste annually (Becon – £240m waste management project for Northern Ireland councils 2023). The project has been contested for nearly ten years. In May 2023 the High Court quashed the most recent decision to deny planning approval for developing the plant. Planning approval will again be considered by the Department for Infrastructure.

4.26 While incineration or energy recovery is preferrable to landfill, recycling and reusing waste is preferable to energy recovery (waste hierarchy.) Looking to improve Northern Ireland’s capacity to reuse and recycle waste in greater quantities is in line with the Green Growth Strategy. Part of this Strategy is the promotion of the green economy and ‘circular jobs.’ As the draft strategy document states, “These jobs will be the result of prioritising regenerative resources, extending the lifetime of products, using waste as a resource, creating value for secondary materials and sharing knowledge on circularity. It will include jobs in repair, waste and resource management, procurement, renewable energy…and more.”

4.27 Reviewing the waste infrastructure is an opportunity to encourage the green economy and to promote green jobs. Those responsible in Northern Ireland for waste management will have to consider what infrastructure is best required to meet the demands of waste management while also considering what options are most environmentally and economically sustainable.

Key Points

The new Waste Management Strategy will have to clearly articulate how future waste targets can be achieved and it is important that it is published by DAERA as soon as possible.

Waste prevention plans and measurable targets are required to reduce overall waste generated, along with a renewed focus on reusing and recycling.

In the context of a circular economy and the move towards Net Zero, the nature of waste management and disposal must be considered. The role of the waste hierarchy should be central in all decision making around waste management and its associated infrastructure, which must be developed in line with Northern Ireland’s overall environmental goals and agenda.